Trees and Shrubs to Watch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pru Nus Contains Many Species and Cultivars, Pru Nus Including Both Fruits and Woody Ornamentals

;J. N l\J d.000 A~ :J-6 '. AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION SERVICE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA • The genus Pru nus contains many species and cultivars, Pru nus including both fruits and woody ornamentals. The arboretum's Prunus maacki (Amur Cherry). This small tree has bright, emphasis is on the ornamental plants. brownish-yellow bark that flakes off in papery strips. It is par Prunus americana (American Plum). This small tree furnishes ticularly attractive in winter when the stems contrast with the fruits prized for making preserves and is also an ornamental. snow. The flowers and fruits are produced in drooping racemes In early May, the trees are covered with a "snowball" bloom similar to those of our native chokecherry. This plant is ex of white flowers. If these blooms escape the spring frosts, tremely hardy and well worth growing. there will be a crop of colorful fruits in the fall. The trees Prunus maritima (Beach Plum). This species is native to the sucker freely, and unless controlled, a thicket results. The A coastal plains from Maine to Virginia. It's a sprawling shrub merican Plum is excellent for conservation purposes, and the reaching a height of about 6 feet. It blooms early with small thickets are favorite refuges for birds and wildlife. white flowers. Our plants have shown varying degrees of die Prunus amygdalus (Almond). Several cultivars of almonds back and have been removed for this reason. including 'Halls' and 'Princess'-have been tested. Although Prunus 'Minnesota Purple.' This cultivar was named by the the plants survived and even flowered, each winter's dieback University of Minnesota in 1920. -

Biscogniauxia Granmoi (Xylariaceae) in Europe

©Österreichische Mykologische Gesellschaft, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Osten. Z.Pilzk 8(1999) 139 Biscogniauxia granmoi (Xylariaceae) in Europe THOMAS L£SS0E CHRISTIAN SCHEUER Botanical Institute, Copenhagen University Institut fiir Botanik der Karl-Franzens-Universitat Oster Farimagsgade 2D Holteigasse 6 DK-1353 Copenhagen K, Denmark A-8010 Graz, Austria e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] ALFRED GRANMO Trornso Museum, University of Tromse N-9037 Tromso, Norway e-mail: [email protected] Received 5. 7. 1999 Key words: Xylariaceae, Biscogniauxia. - Taxonomy, distribution. - Fungi of Europe, Asia. Abstract: Biscogniauxia granmoi, growing on Prunus padus (incl. var. pubescens = Padus asiatica) is reported from Europe and Asia, with material from Austria, Latvia, Norway, Poland, and Far Eastern Russia. It is compared with B. nummulana s. str., B. capnodes and B. simphcior. The taxon was included in the recent revision of Biscogniauxia by JU & al. {1998, Mycotaxon 66: 50) under the name "B. pruni GRANMO, L/ESS0E & SCHEUER" nom. prov. Zusammenfassung: Biscogniauxia granmoi, die bisher ausschließlich auf Prunus padus (inkl. var pubescens = Padus asiatica) gefunden wurde, wird aufgrund von Aufsammlungen aus Europa und Asien vorgestellt. Die bisherigen Belege stammen aus Österreich, Litauen, Norwegen, Polen und dem femöstlichen Teil Rußlands. Die Unterschiede zu B. nummulana s. Str., B. capnodes und H simphaor werden diskutiert. Dieses Taxon wurde unter dem Namen "B. pruni Granmo, l.aessoe & Scheuer" nom. prov. schon von JU & al. (1998, Mycotaxon 66: 50) in ihre Revision der Gattung Biscogniauxia aufge- nommen. The genus Biscogniauxia KUNTZE (Xylariaceae) was resurrected and amended by POUZAR (1979, 1986) for a group of Xylariaceae with applanate dark stromata that MILLER (1961) treated in Hypoxylon BULL., and for a group of species with thick, discoid stromata formerly placed in Nummularia TUL. -

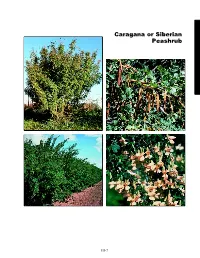

Caragana Or Siberian Peashrub

Caragana or Siberian Peashrub slide 5a 400% slide 5b 360% slide 5d slide 5c 360% 360% III-7 Caragana or Environmental Requirements Siberian Peashrub Soils Soil Texture - Adapted to a wide range of soils. (Caragana Soil pH - 5.0 to 8.0. arborescens) Windbreak Suitability Group - 1, 1K, 3, 4, 4C, 5, 6D, 6G, 8, 9C, 9L. General Description Cold Hardiness USDA Zone 2. Drought tolerant legume, long-lived, alkaline-tolerant, tall shrub native to Siberia. Ability to withstand extreme cold Water and dryness. Major windbreak species. Drought tolerant. Does not perform well on very wet or very dry sandy soils. Leaves and Buds Bud Arrangement - Alternate. Light Bud Color - Light brown, chaffy in nature. Full sun. Bud Size - 1/8 inch, weakly imbricate. Leaf Type and Shape - Pinnately-compound, 8 to 12 Uses leaflets per leaf. Conservation/Windbreaks Leaf Margins - Entire. Medium to tall shrub for farmstead and field windbreaks Leaf Surface - Pubescent in early spring, later glabrescent. and highway beautification. Leaf Length - 1½ to 3 inches; leaflets 1/2 to 1 inch. Wildlife Leaf Width - 1 to 2 inches; leaflets 1/3 to 2/3 inch. Used for nesting by several species of songbirds. Food Leaf Color - Light-green, become dark green in summer; source for hummingbirds. yellow fall color. Agroforestry Products Flowers and Fruits No known products. Flower Type - Small, pea-like. Flower Color - Showy yellow in spring. Urban/Recreational Fruit Type - Pod, with multiple seeds. Pods open with a Screening and border, ornamental flowers in spring. popping sound when ripe. Cultivated Varieties Fruit Color - Brown when mature. -

Legumes of the North-Central States: C

LEGUMES OF THE NORTH-CENTRAL STATES: C-ALEGEAE by Stanley Larson Welsh A Dissertation Submitted, to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major Subject: Systematic Botany Approved: Signature was redacted for privacy. Signature was redacted for privacy. artment Signature was redacted for privacy. Dean of Graduat College Iowa State University Of Science and Technology Ames, Iowa I960 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii INTRODUCTION 1 HISTORICAL ACCOUNT 3 MATERIALS AND METHODS 8 TAXONOMIC AND NOMENCLATURE TREATMENT 13 REFERENCES 158 APPENDIX A 176 APPENDIX B 202 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer wishes to express his deep gratitude to Professor Duane Isely for assistance in the selection of the problem and for the con structive criticisms and words of encouragement offered throughout the course of this investigation. Support through the Iowa Agricultural Experiment Station and through the Industrial Science Research Institute made possible the field work required in this problem. Thanks are due to the curators of the many herbaria consulted during this investigation. Special thanks are due the curators of the Missouri Botanical Garden, U. S. National Museum, University of Minnesota, North Dakota Agricultural College, University of South Dakota, University of Nebraska, and University of Michigan. The cooperation of the librarians at Iowa State University is deeply appreciated. Special thanks are due Dr. G. B. Van Schaack of the Missouri Botanical Garden library. His enthusiastic assistance in finding rare botanical volumes has proved invaluable in the preparation of this paper. To the writer's wife, Stella, deepest appreciation is expressed. Her untiring devotion, work, and cooperation have made this work possible. -

Netted Mountain Moth in Scotland

Managing land for the Netted Mountain Moth Ensuring the long-term survival of the Netted Mountain Moth, as with many other species, is probably more likely if sites are linked, enabling an exchange of adults between neighbouring colonies. The loss of suitable habitat can be damaging by making the surviving populations more fragmented and thus isolated. The precise habitat requirements are not fully understood, however, the following general principles should benefit the Netted Mountain Moth. learn about the The fortunes of the Netted Mountain Moth are directly linked to the presence of extensive areas of bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi). Bearberry favours dry or gravelly soil and can be locally abundant on the drier moorland characteristic of the eastern and central Highlands. Netted Mountain Moth This habitat is often referred to as “Arctostaphylos heath”. If Arctostaphylos heath is not burnt, then bearberry can become scarce as heather slowly dominates. In the absence of controlled burning, bearberry can maintain its presence on disturbed ground, especially steep slopes, track and verge sides or in more exposed conditions usually at higher altitudes under natural erosion. However, it is thought that the Netted Mountain Moth does not favour these more exposed sites. Some Netted Mountain Moth sites have been lost due to afforestation, whilst over-grazing by sheep and/or deer, and both uncontrolled and a cessation of burning can also be detrimental. Good muirburn practice that creates a patchwork of small burns on a 7-10 year cycle is beneficial, and on some sites essential. Light grazing may also be desirable giving bearberry May 2004 an advantage over heather. -

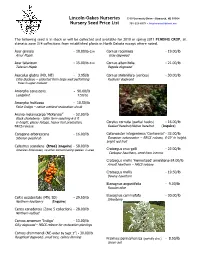

Nursery Price List

Lincoln-Oakes Nurseries 3310 University Drive • Bismarck, ND 58504 Nursery Seed Price List 701-223-8575 • [email protected] The following seed is in stock or will be collected and available for 2010 or spring 2011 PENDING CROP, all climatic zone 3/4 collections from established plants in North Dakota except where noted. Acer ginnala - 18.00/lb d.w Cornus racemosa - 19.00/lb Amur Maple Gray dogwood Acer tataricum - 15.00/lb d.w Cornus alternifolia - 21.00/lb Tatarian Maple Pagoda dogwood Aesculus glabra (ND, NE) - 3.95/lb Cornus stolonifera (sericea) - 30.00/lb Ohio Buckeye – collected from large well performing Redosier dogwood Trees in upper midwest Amorpha canescens - 90.00/lb Leadplant 7.50/oz Amorpha fruiticosa - 10.50/lb False Indigo – native wetland restoration shrub Aronia melanocarpa ‘McKenzie” - 52.00/lb Black chokeberry - taller form reaching 6-8 ft in height, glossy foliage, heavy fruit production, Corylus cornuta (partial husks) - 16.00/lb NRCS release Beaked hazelnut/Native hazelnut (Inquire) Caragana arborescens - 16.00/lb Cotoneaster integerrimus ‘Centennial’ - 32.00/lb Siberian peashrub European cotoneaster – NRCS release, 6-10’ in height, bright red fruit Celastrus scandens (true) (Inquire) - 58.00/lb American bittersweet, no other contaminating species in area Crataegus crus-galli - 22.00/lb Cockspur hawthorn, seed from inermis Crataegus mollis ‘Homestead’ arnoldiana-24.00/lb Arnold hawthorn – NRCS release Crataegus mollis - 19.50/lb Downy hawthorn Elaeagnus angustifolia - 9.00/lb Russian olive Elaeagnus commutata -

Tree Identification Guide

2048 OPAL guide to deciduous trees_Invertebrates 592 x 210 copy 17/04/2015 18:39 Page 1 Tree Rowan Elder Beech Whitebeam Cherry Willow Identification Guide Sorbus aucuparia Sambucus nigra Fagus sylvatica Sorbus aria Prunus species Salix species This guide can be used for the OPAL Tree Health Survey and OPAL Air Survey Oak Ash Quercus species Fraxinus excelsior Maple Hawthorn Hornbeam Crab apple Birch Poplar Acer species Crataegus monogyna Carpinus betulus Malus sylvatica Betula species Populus species Horse chestnut Sycamore Aesculus hippocastanum Acer pseudoplatanus London Plane Sweet chestnut Hazel Lime Elm Alder Platanus x acerifolia Castanea sativa Corylus avellana Tilia species Ulmus species Alnus species 2048 OPAL guide to deciduous trees_Invertebrates 592 x 210 copy 17/04/2015 18:39 Page 1 Tree Rowan Elder Beech Whitebeam Cherry Willow Identification Guide Sorbus aucuparia Sambucus nigra Fagus sylvatica Sorbus aria Prunus species Salix species This guide can be used for the OPAL Tree Health Survey and OPAL Air Survey Oak Ash Quercus species Fraxinus excelsior Maple Hawthorn Hornbeam Crab apple Birch Poplar Acer species Crataegus montana Carpinus betulus Malus sylvatica Betula species Populus species Horse chestnut Sycamore Aesculus hippocastanum Acer pseudoplatanus London Plane Sweet chestnut Hazel Lime Elm Alder Platanus x acerifolia Castanea sativa Corylus avellana Tilia species Ulmus species Alnus species 2048 OPAL guide to deciduous trees_Invertebrates 592 x 210 copy 17/04/2015 18:39 Page 2 ‹ ‹ Start here Is the leaf at least -

Chokecherry Prunus Virginiana L

chokecherry Prunus virginiana L. Synonyms: Prunus virginiana ssp. demissa (Nutt.) Roy L. Taylor & MacBryde, P. demissa (Nutt.) Walp. Other common names: black chokecherry, bitter-berry, cabinet cherry, California chokecherry, caupulin, chuckleyplum, common chokecherry, eastern chokecherry, jamcherry, red chokecherry, rum chokecherry, sloe tree, Virginia chokecherry, western chokecherry, whiskey chokecherry, wild blackcherry, wild cherry Family: Rosaceae Invasiveness Rank: 74 The invasiveness rank is calculated based on a species’ ecological impacts, biological attributes, distribution, and response to control measures. The ranks are scaled from 0 to 100, with 0 representing a plant that poses no threat to native ecosystems and 100 representing a plant that poses a major threat to native ecosystems. Description Similar species: Several non-native Prunus species can Chokecherry is a deciduous, thicket-forming, erect shrub be confused with chokecherry in Alaska. Unlike or small tree that grows 1 to 6 m tall from an extensive chokecherry, which has glabrous inner surfaces of the network of lateral roots. Roots can extend more than 10 basal sections of the flowers, European bird cherry m horizontally and 2 m vertically. Young twigs are often (Prunus padus) has hairy inner surfaces of the basal hairy. Stems are numerous, slender, and branched. Bark sections of the flowers. Chokecherry can also be is smooth to fine-scaly and red-brown to grey-brown. differentiated from European bird cherry by its foliage, Leaves are alternate, elliptic to ovate, and 3 to 10 cm which turns red in late summer and fall; the leaves of long with pointed tips and toothed margins. Upper European bird cherry remain green throughout the surfaces are green and glabrous, and lower surfaces are summer. -

Auglaize County Weekly Horticulture Newsletter – 1-10-20 the Spider

Ohio State University Extension Auglaize County Top of Ohio EERA 208 South Blackhoof Street Wapakoneta, OH 45895-1902 419-739-6580 Phone 419-739-6581 Fax www.auglaize.osu.edu OSU Extension - Auglaize County Weekly Horticulture Newsletter – 1-10-20 The Spider Plant The spider plant name comes from the “spidery” look of the baby plants that grow rapidly. Another common name for the plant is airplane plant. The scientific name is Chlorophytum comosum. The spider plant is native to coastal areas of South Africa. The spider plant is a monocot meaning it has parallel leaf venation and is in the lily family. The spider plant is a clump-forming perennial. The leaves are long and narrow with a fairly prominent mid- rib. The leaves are somewhat folded or in a v-shaped pattern, especially at the base of the plant. Flower stems are stiff, wiry, and long. At the end of the flower stem plantlets begin to form. Flowers are white having three petals and three sepals. The flower is 0.25 to 0.75 inch in diameter. Spider plants have thick fleshy roots that store food reserves, making the plant perennial. There are four common varieties or cultivars of the spider plant. The native plant has a solid green leaf color with a lighter green color in the center of the leaf. The ‘Mandaianum’ variety is a dwarf spider plant with 4-6 inch dark green leaves with a bright yellow stripe. The ‘Vittatum’ variety is the most common cultivated Ohio State University Extension Auglaize County Top of Ohio EERA 208 South Blackhoof Street Wapakoneta, OH 45895-1902 419-739-6580 Phone 419-739-6581 Fax www.auglaize.osu.edu variety through the late 1990’s. -

Uva Ursi Max-V Bearberry for Urinary Health

PRODUCT DATA DOUGLAS LABORATORIES® 08/2013 1 Uva Ursi Max-V Bearberry for urinary health DESCRIPTION Uva-Ursi Max-V, provided by Douglas Laboratories, supplies 200 mg of standardized Uva Ursi and 100 mg of non-standardized leaf in a vegetarian capsule. FUNCTIONS Uva Ursi (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), also known as bearberry, is a low-lying evergreen shrub found in Canada, Europe, and Asia. It has been used traditionally as a diuretic, astringent and urinary antiseptic for several hundred years. One of the active components in it, arbutin, releases hydroquinone, which can provide support for a healthy urinary tract.† FORMULA (#77379) Each capsule contains: Uva ursi Herbal extract ...................................................200 mg (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi L.Spreng) (Standardized to provide 40 mg (20%) arbutin) Uva Ursi (leaf) non-standardized…………………………100 mg SUGGESTED USE Adults take 1 capsule daily between meals or as directed by a healthcare professional. Not intended for long- term use. Do not take if pregnant or lactating. SIDE EFFECTS Uva ursi may cause nausea, vomiting, gastrointestinal discomfort, and a greenish-brown discoloration of the urine. Uva ursi contains hydroquinone which inhibits melanin synthesis and might lead to retinal thinning if used long-term. Chronic use, especially in children, can cause liver impairment due to its tannin content. STORAGE Store in a cool, dry place, away from direct light. Keep out of reach of children. REFERENCES Beaux D, Fleurentin J, Mortier F. Effect of extracts of Orthosiphon stamineus Benth, Hieracium pilosella L., Sambucus nigra L. and Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (L.) Spreng. in rats. Phytother Res 1999 May;13(3):222-5 Grases F, Melero G, Costa-Bauza A, Prieto R, March JG. -

Buyers of Timber in Rowan County

Companies that Buy Timber In County: Rowan 7/7/2021 COMPANY PHONE, FAX, EMAIL and SPECIES PRODUCTS ADDRESS CONTACT PERSON PURCHASED PURCHASED Appalachian Walnut Co. LLC PHONE 980-241-0397 Ash, White Oak, Walnut Standing Timber, Sawlogs, 219 Rock Hill Lane FAX: 704-735-3020 Lumber, Veneer Lincolnton, NC 28092 EMAIL: [email protected] Cole Sain, Owner/Log Buyer Associated Hardwoods, Inc. PHONE 828-396-3321 Ash, Basswood, American Beech, Black Standing Timber, Sawlogs 650 North Main Street FAX: 828-396-6202 Cherry, Hickory, Hard Maple, Soft Maple, Red Oak, White Oak, Sweetgum, Granite Falls, NC 29650 EMAIL: Black/Tupelo Gum, Walnut, Yellow-Poplar [email protected] Art Howard, Log Buyer Austin Hunt Lumber Co. PHONE 704-878-9784 S Yellow Pine, Ash, Basswood, American Standing Timber, Sawlogs 2762 Hickory Hwy FAX: 704-878-9785 Beech, Black Cherry, Hickory, Black Walnut, Yellow-Poplar, Soft Maple, Red Statesville, NC 28677 EMAIL: Oak, White Oak, Other Hardwoods [email protected]; visionairllc@ Ray N. Hunt, President Barkclad Natural Products, Inc. PHONE (828)648-6092 Yellow-Poplar Standing Timber, Sawlogs, 217 Bethel Drive FAX: (828)648-9028 Poles Canton, NC 28716 EMAIL: [email protected] Danny Heatherly, President Billy Speaks & Sons Logging & Ch PHONE (704)682-0671 All Hardwoods, All Softwoods Standing Timber, Sawlogs, 252 Hunting Creek Rd. FAX: Pulpwood Hamptonville, NC 27020 EMAIL: [email protected] Billy Speaks, Owner Blue Chip Wood Products PHONE (919)805-0060 All Hardwoods, All Softwoods Standing Timber, Sawlogs, FAX: Pulpwood , NC EMAIL: [email protected] Bill Baxley Boise Cascade - Chester Plywood PHONE (803)581-7164 S. Yellow Pine, Other Softwoods, Yellow Standing Timber, Ply or Veneer 1445 Lancaster Hwy FAX: Poplar, Sweetgum, Soft Maple, Logs Black/Tupelo Gum, Other Hardwoods Chester, SC 29706-1110 EMAIL: [email protected] Russell Hatcher, Procurement Manager This is a list of individuals that purchase standing timber and have requested that their information be posted on the N.C. -

And Natural Community Restoration

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR LANDSCAPING AND NATURAL COMMUNITY RESTORATION Natural Heritage Conservation Program Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources P.O. Box 7921, Madison, WI 53707 August 2016, PUB-NH-936 Visit us online at dnr.wi.gov search “ER” Table of Contents Title ..……………………………………………………….……......………..… 1 Southern Forests on Dry Soils ...................................................... 22 - 24 Table of Contents ...……………………………………….….....………...….. 2 Core Species .............................................................................. 22 Background and How to Use the Plant Lists ………….……..………….….. 3 Satellite Species ......................................................................... 23 Plant List and Natural Community Descriptions .…………...…………….... 4 Shrub and Additional Satellite Species ....................................... 24 Glossary ..................................................................................................... 5 Tree Species ............................................................................... 24 Key to Symbols, Soil Texture and Moisture Figures .................................. 6 Northern Forests on Rich Soils ..................................................... 25 - 27 Prairies on Rich Soils ………………………………….…..….……....... 7 - 9 Core Species .............................................................................. 25 Core Species ...……………………………….…..…….………........ 7 Satellite Species ......................................................................... 26 Satellite Species