Pdf/Actualizado/176595.Pdf Santiago, Chile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Factors for Success of Sunnah Movement in Perlis State

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 10, No. 4, April, 2020, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2020 HRMARS Factors for Success of Sunnah Movement in Perlis State Abdul Ghafur Abdul Hadi and Basri Ibrahim To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i4/7137 DOI:10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i4/7137 Received: 18 February 2020, Revised: 04 March 2020, Accepted: 26 March 2020 Published Online: 10 April 2020 In-Text Citation: (Hadi & Ibrahim, 2020) To Cite this Article: Hadi, A. G. A., & Ibrahim, B. (2020). Factors for Success of Sunnah Movement in Perlis State. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 10(4), 336–347. Copyright: © 2020 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 10, No. 4, 2020, Pg. 336 - 347 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 336 International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 10, No. 4, April, 2020, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2020 HRMARS Factors for Success of Sunnah Movement in Perlis State Abdul Ghafur Abdul Hadi1 and Basri Ibrahim2 1Universiti Islam Malaysia, Cyberjaya, Malaysia, 2Universiti Islam Malaysia, Cyberjaya, Malaysia/ Faculty of Islamic Contemporary Studies, Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin, Terengganu, Malaysia. -

Distribution and Analysis of Heavy Metals Contamination in Soil, Perlis, Malaysia

E3S Web of Conferences 34, 02040 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/20183402040 CENVIRON 2017 Distribution and Analysis of Heavy Metals Contamination in Soil, Perlis, Malaysia Ain Nihla Kamarudzaman1,*, Yee Shan Woo1, and Mohd Faizal Ab Jalil2 1School of Environmental Engineering, Universiti Malaysia Perlis, Kompleks Pusat Pengajian Jejawi 3, 02600 Arau, Perlis, Malaysia 2Perlis State Department of Environment, 2nd Floor, KWSP Building, Jalan Bukit Lagi, 01000 Kangar, Perlis, Malaysia Abstract. The concentration of six heavy metals such as Cu, Cr, Ni, Cd, Zn and Mn were studied in the soils around Perlis. The aim of the study is to assess the heavy metals contamination distribution due to industrialisation and agricultural activities. Soil samples were collected at depth of 0 – 15 cm in five stations around Perlis. The soil samples are subjected to soil extraction and the concentration of heavy metals was determined via ICP - OES. Overall concentrations of Cr, Cu, Zn, Ni, Cd and Mn in the soil samples ranged from 0.003 - 0.235 mg/L, 0.08 - 41.187 mg/L, 0.065 - 45.395 mg/L, 0.031 - 2.198 mg/L, 0.01 - 0.174 mg/L and 0.165 - 63.789 mg/L respectively. The concentration of heavy metals in the soil showed the following decreasing trend, Mn > Zn > Cu > Ni > Cr > Cd. From the result, the level of heavy metals in the soil near centralised Chuping industrial areas gives maximum value compared to other locations in Perlis. As a conclusion, increasing anthropogenic activities have influenced the environment, especially in increasing the pollution loading. -

Jumlah 74 Sekolah Rendah Di Negeri Perlis Sepanjang 2012

www.myschoolchildren.com www.myschoolchildren.com BIL NEGERI DAERAH PPD KOD SEKOLAH NAMA SEKOLAH ALAMAT LOKASI BANDAR POSKOD LOKASI NO. TELEFON NO.FAKS L P ENROLMEN 1 PERLIS JPN PERLIS RBA0001 SK ABI JALAN ABI BATAS PAIP KANGAR 01000 Luar Bandar 049760912 049760912 175 147 322 2 PERLIS JPN PERLIS RBA0002 SEK TENGKU BUDRIAH JALAN BESAR ARAU ARAU 02600 Luar Bandar 049861212 049861212 497 452 949 3 PERLIS JPN PERLIS RBA0003 SK BESERI KM 12, JLN KAKI BUKIT, BESERI KANGAR 02400 Luar Bandar 049381516 049381516 274 235 509 4 PERLIS JPN PERLIS RBA0004 SK BINTONG JALAN RAJA SYED SAFFI, KANGAR 01000 Luar Bandar 049760507 049760507 152 154 306 5 PERLIS JPN PERLIS RBA0005 SK BOHOR MALI JALAN KANGAR-ALOR SETAR SIMPANG EMPAT 02700 Luar Bandar 049808470 049805890 92 91 183 6 PERLIS JPN PERLIS RBA0006 SK RAJA PEREMPUAN BUDRIAH CHEMUMAR, SIMPANG EMPAT SIMPANG EMPAT 02700 Luar Bandar 049472934 049472934 69 95 164 7 PERLIS JPN PERLIS RBA0007 SK CHUPING JALAN CHUPING MATA AYER 02500 Luar Bandar 049381677 049381677 155 135 290 8 PERLIS JPN PERLIS RBA0009 SK DATO KAYAMAN BT.2 1/2 JALAN DATO' KAYAMAN BUKIT KETERI 02450 Luar Bandar 049384393 049384390 161 204 365 9 PERLIS JPN PERLIS RBA0010 SK GUAR NANGKA GUAR NANGKA MATA AYER 02500 Luar Bandar 049863562 049862091 210 185 395 10 PERLIS JPN PERLIS RBA0011 SK JEJAWI JALAN KANGAR-ARAU, KANGAR 01000 Bandar 049768545 049778545 265 278 543 11 PERLIS JPN PERLIS RBA0012 SK JELEMPOK KAMPUNG JELEMPOK. ARAU 02600 Luar Bandar 049862469 049862469 111 111 222 12 PERLIS JPN PERLIS RBA0013 SK KAMPONG SALANG KM. -

Business Name Business Category Outlet Address State Cakra Enam

Business Name Business Category Outlet Address State cakra enam puluh sembilan Automotive 21 Jalan Dua Kampung Tok Larak 01000 Kangar Perlis Malaysia Perlis CITY ELECTRICAL SERVICE Automotive Persiaran Jubli Emas Kampung Jejawi Kangar Perlis Perlis EEAUTOSPRAYENTERPRISE Automotive Jalan Padang Behor Taman Desa Pulai Kangar Perlis Perlis ESRMOTOR Automotive no 9 bangunan mara bazar mara Kuala Perlis Service Centre Lot 245 Jalan Besar Pekan Kuala Perlis Pekan Kuala Perlis 02000 Kuala Perlis Perlis Malaysia Perlis kiang tyre battery ali Automotive seriab b21 No 23 Jalan Kangar Alor Setar Taman Pertiwi Kangar Perlis Perlis Lim Car Air Cond Automotive Kampung Kersih Mata Ayer1 Malaysia Kampung Mata Ayer Kangar Perlis Perlis Min Honky Auto Parts Kangar Automotive 30 & 32 JALAN KANGAR-ALOR SETAR TAMAN PERTIWI INDAH KangarPLS - Perlis Perlis power auto accessories Automotive power auto acc no4 6 Jalan Seruling Pusat Bandar Kangar Kangar Perlis Perlis SBS BISTARI ENTERPRISE Automotive SBS BISTARI ENTERPRISE 88B BLOK 10 Jalan Kenari Felda Chuping 02500 Kangar Perlis Malaysia Perlis Tai Hoong Auto Automotive 4150, jalan heng choon thiam, Butterworth, Penang, Malaysia Perlis tcs electric trading Automotive tcs batu 1 1/4 Jalan Kangar Padang Besar Taman Sena Indah Kangar Perlis Perlis TADIKA SHIMAH Education No 19, Lorong Ciku 2,, Kampung Guru, Fasa 3, Tingkat 9 bangunan KWSP, , Pusat Bandar Kangar, Kangar, Perlis, Malaysia Perlis AMS BRAND ENTERPRISE Entertainment, Lifestyle & Sports No D2, Villa Semi-D, Jalan Kuala Perlis, Perlis chop toh lee Entertainment, -

Senarai Premis Yang Berjaya Mendapat Pensijilan (Mesti)

SENARAI PREMIS YANG BERJAYA MENDAPAT PENSIJILAN (MESTI) BIL NAMA SYARIKAT ALAMAT SYARIKAT NAMA WAKIL SYARIKAT NO TELEFON PRODUK LOT 19, JALAN INDUSTRI, KAWASAN PERINDUSTRIAN, 02000 Tel: 04-9853089 1 IGLOO ICE SDN BHD CHUA SHUI CHWN AIS KUALA PERLIS Faks: 04-9853122 2 RAROSYA ENTERPRISE 42 KAMPUNG BANGGOL SENA KANGAR RAFEDAH BINTI ISMAIL@MUSA 017-5121048 SOS CILI KOMPLEKS GERAK TANI WAWASAN E-1 (MADA) 02700 SIMPANG 3 PPK E-1 SIMPANG EMPAT EMPAT AL-HIDAYAH BT ALIAS 04-9807248 / 012-5883542 MINI POPIA PERLIS LOT 7 & 8, KAWASAN PERINDUSTRIAN MIEL JEJAWI FASA 2, 013-5846717 / 4 HPA INDUSTRIES SDN. BHD. A. ZAKARIA ABU BAKAR / NORASYIKIN KOPI RADIX, RADIX DIET JALAN JEJAWI SEMATANG, 02600 ARAU, PERLIS 019-6330727/049760741 5 SBA FOOD ENTERPRISE AB, JALAN KG SYED OMAR 01000 KANGAR SARIMAH BT ANI 017-5319490 REMPEYEK NO. 5&6, KAW PERINDUSTRIAN RINGAN, JALAN BESAR 02100 6 MEGA DUTAMAS SDN. BHD. TEOH YICK XIANG 017-4128967 COKLAT PADANG BESAR, PERLIS LOT A-5, KAWASAN MIEL, JEJAWI PHASE 1, 02600 JEJAWI, 019-4752188 7 ATLAS EDIBLE ICE SDN BHD LOW BEE BEE Ais tiub & Ais hancur PERLIS. 04-9777388 019-4907826 NO 2, 4 & 6, JALAN MURAI BATU, TAMAN KIM, 02100 PADANG 8 MEGA DUTAMAS SDN. BHD. YAP YUEN SER 04-9492788 COKLAT BESAR, PERLIS 04-9491788(F) 9 TERIAU ENTERPRISE NO 12 A KAMPUNG GUAR UJUNG BATU UTAN AJI 01000 KANGAR JAMINAH BT TERIAH 04-9766071 KACANG BERSALUT 109, LORONG SRI INAI, KAMPUNG JEJAWI DALAM 02600 ARAU 10 FAUZIAH BT ISMAIL FAUZIAH BINTI ISMAIL 017-4614385 REMPEYEK PERLIS LOT 555, JALAN BATAS LINTANG, 02700 SIMPANG EMPAT, 11 PERUSAHAAN PASTA ITIFAQ MOHD TARMIZIE ROMLI 017-5568953 MEE KUNING PERLIS 019-4549889 PERTUBUHAN PELADANG KAWASAN PAYA, KM 4 JALAN KAKI 12 PPK PAYA RAHMAH BT SALAMAT 04-9760280 CIP BUAH-BUAHAN BUKIT, 01000 KANGAR PERLIS 04-9761140 13 SYAFI BAKERY 500, JALAN MASJID KG. -

Capabilities for Mass Market Innovations in Emerging Economies

Capabilities for Mass Market Innovations in Emerging Economies Rifat Sharmelly MSc, B.IT (Hons.) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The UNSW Business School (School of Management), The University of New South Wales, Sydney Australia 2016 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed ……………………………………………........... Date ……………………………………………............... 2 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT ‘I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. I also authorise University Microfilms to use the 350 word abstract of my thesis in Dissertation Abstract International (this is applicable to doctoral theses only). -

Company Description

Analysis of Strategic Alliance with Ford MINOR PROJECT REPORT ON STRATEGIC ALLIANCES – FORD MOTOR COMPANY BUILT FOR THE ROAD AHEAD. Submitted for fulfillment of the requirement for the award of the degree of Bachelor of Business Administration To Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University Under the guidance of: Mrs. Nidhi Prasad Submitted by: Sandeep Singh Sethi 1 SANDEEP SINGH Analysis of Strategic Alliance with Ford Roll No.: 05910601709 ANSAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY TO WHOMSOEVER IT MAY CONCERN This is to certify that the minor project report titled STRATEGIC ALLIANCES – FORD MOTOR COMPANY carried out by SANDEEP SINGH has been accomplished under my guidance and supervision as a duly registered BBA student of the ANSAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY (G.G.S I.P. University, New Delhi). This project is being submitted by him in the partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the Bachelor of Business Administration from I.P. University. His dissertation represents his original work and is worthy of consideration for the award of the degree of Bachelor of Business Administration. ____________________ (Name and Signature of the Internal Faculty Advisor) Title: Date: 2 SANDEEP SINGH Analysis of Strategic Alliance with Ford ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Project Report is the outcome of many individuals without whom it cannot be molded, so they deserve thanks. I thank my teacher, Mrs. Nidhi Prasad under whose guidance I have been able to successfully complete this project. I thank all of my friends and fellow classmates for their assistance in this project. – Sandeep Singh 3 SANDEEP SINGH Analysis of Strategic Alliance with Ford CONTENTS Page no. -

The Sanai Limestone Member a Devonian Limestone Unit in Perlis

Geological Society of Malaysia, Bulletin 46 May 2003; pp. 137-141 The Sanai Limestone Member a Devonian limestone unit in Perlis MEOR HAKIF HASSAN AND LEE CHAI PENG Department of Geology University of Malaya 50603 Kuala Lumpur Abstract: The name Sanai Limestone Member is proposed for the thin limestone unit located inside the Jentik Formation, previously known as Unit 4. Stratigraphically it is located near the top of the Jentik Formation, underlain by Mid or Late Devonian red mudstone beds of Unit 3, and overlain by light coloured to black mudstones interbedded with cherts of Unit 5. The lithology consists of planar bedded, grey micritic limestone, with thin shale partings and stylolites. The limestone contains abundant fossils of conodonts, styliolinids, straight cone nautiloids, and trilobites. The occurrence of the conodont Palmatolepis glabra indicates a Late Devonian, Fammenian age. The depositional environment of the Sanai Limestone Member is interpreted to be a deepwater pelagic limestone facies, located at the outer shelf to continental margin region. INTRODUCTION Formation such as Kampung Binjal and Wang Kelian. The Langgun Island section is incomplete, and does not preserve In the first report on the newly proposed Jentik the part where the Sanai Limestone Member is expected to Formation (Meor and Lee, 2002a), we briefly described a have been located. limestone bed at the base of Section 2 of Hill B of the composite stratotype in Kampung Guar Jentik (Fig. 4, Stratigraphy Meor and Lee, 2002a), which we left informally named as The Sanai Limestone Member is oriented north Unit 4. More detailed logging and field description have northwest, south-southeast, and dips steeply towards the produced much more information on this unit. -

MARITIME Security &Defence M

June MARITIME 2021 a7.50 Security D 14974 E &Defence MSD From the Sea and Beyond ISSN 1617-7983 • Key Developments in... • Amphibious Warfare www.maritime-security-defence.com • • Asia‘s Power Balance MITTLER • European Submarines June 2021 • Port Security REPORT NAVAL GROUP DESIGNS, BUILDS AND MAINTAINS SUBMARINES AND SURFACE SHIPS ALL AROUND THE WORLD. Leveraging this unique expertise and our proven track-record in international cooperation, we are ready to build and foster partnerships with navies, industry and knowledge partners. Sovereignty, Innovation, Operational excellence : our common future will be made of challenges, passion & engagement. POWER AT SEA WWW.NAVAL-GROUP.COM - Design : Seenk Naval Group - Crédit photo : ©Naval Group, ©Marine Nationale, © Ewan Lebourdais NAVAL_GROUP_AP_2020_dual-GB_210x297.indd 1 28/05/2021 11:49 Editorial Hard Choices in the New Cold War Era The last decade has seen many of the foundations on which post-Cold War navies were constructed start to become eroded. The victory of the United States and its Western Allies in the unfought war with the Soviet Union heralded a new era in which navies could forsake many of the demands of Photo: author preparing for high intensity warfare. Helping to ensure the security of the maritime shipping networks that continue to dominate global trade and the vast resources of emerging EEZs from asymmetric challenges arguably became many navies’ primary raison d’être. Fleets became focused on collabora- tive global stabilisation far from home and structured their assets accordingly. Perhaps the most extreme example of this trend has been the German Navy’s F125 BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG class frig- ates – hugely sophisticated and expensive ships designed to prevail only in lower threat environments. -

Iccrbrief Vol. 18 No.6, 1989

ICCRBrief Vol. 18 No.6, 1989 White Wheels of Fortune: Ford and GM in South Africa After decades at the top of the South reevaluated their involvement in South the largest union, the non-racial Na African motor industry, both Ford and Africa. When rumors surfaced that Ford tional Automobile and Allied Workers General Motors moved during might be pulling out, analysts sensed an Union (NAA WU). 1987 -1988 to end all direct investment in important turning point in the history of the country. But neither withdrawal was the industry. Companies like Alfa GENERAL MOTORS: "Braaivleis, what it appeared to be. Both companies Romeo, Peugeot, Renault and Leyland, Rugby, Sunny Skies and Chevrolet" continue to play important behind-the though neither large nor influential in The Ford-Amcar merger left scenes roles in South Africa. They re South Africa, abandoned commercial General Motors as the only wholly- own main a prominent focus for the antiapar manufacturing there. ed American motor vehicle manufac theid movement because of their contin turer in South Africa. GM had followed uing ties to their former South African The Ford-Amcar Merger of 1985 Ford to South Africa in 1926, and like subsidiaries, because of the controversial Ford, chose to build its assembly plant in way in which they sold their South In mid-1984 Ford .secretly began Port Elizabeth. Over the years GM and African assets and because their suc negotiating with Anglo-American's car Ford shared top billing as the leading cessors have resumed vehicle sales to the making company, Amcar, over a possi manufacturers. -

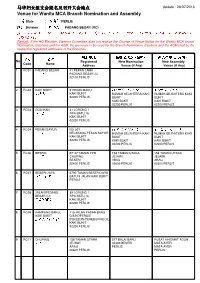

Venue for Wanita MCA Branch Nomination and Assembly 马华妇女

马华妇女组支会提名及召开大会地点 Update : 26/07/2013 Venue for Wanita MCA Branch Nomination and Assembly 州属 State : 玻璃市 PERLIS 区会 Division : 巴冬勿杀 PADANG BESAR (RC ) 注注注:如果总部选举指导委员会没有收到更换提名、大会或选举地点通知,妇女组支会的提名、大会或选举地点必须是该支 会的注册地址。 Remark : If the HQ Elections Steering Committee does not receive the Change of Venue Notice for the Wanita MCA branch Nomination, Elections and the AGM, the premises to be used for the Branch Nomination, Elections and the AGM shall be the respective registered addresses of the Branches. 注册地址 新提名地点(((如有(如有))) 新大会地点(((如有(如有))) 编号 名称 No Registered New Nomination New Assembly Code Name Address Venue (if Any) Venue (if Any) 1 RC01 PADANG BESAR 41 PEKAN LAMA 巴冬勿杀 PADANG BESAR (U) 02100 PERLIS 2 RC02 KAKI BUKIT 5 PEKAN BARU 加基武吉老人院礼堂 加基武吉老人院礼堂 加基武吉 KAKI BUKIT RUMAH SEJAHTERA KAKI RUMAH SEJAHTERA KAKI 02200 PERLIS BUKIT BUKIT KAKI BUKIT KAKI BUKIT 02200 PERLIS 02200 PERLIS 3 RC03 GUA IKAN 31 LORONG 1 拿督公 RPA BATU 16 KAKI BUKIT 02200 PERLIS 4 RC04 PEKAN SAYUR NO 307 加基武吉老人院礼堂 加基武吉老人院礼堂 长江寮 BELAKANG PEKAN SAYOR RUMAH SEJAHTERA KAKI RUMAH SEJAHTERA KAKI KAKI BUKIT BUKIT BUKIT 02200 PERLIS KAKI BUKIT KAKI BUKIT 02200 PERLIS 02200 PERLIS 5 RC06 BESERI EF 47 TAMAN PPB 158 TAMAN UTARA 158 TAMAN UTARA 柏斯里 CHUPING JEJAWI JEJAWI BESERI ARAU ARAU 02400 PERLIS 02600 PERLIS 02600 PERLIS 6 RC07 BESERI JAYA 2790 TAMAN BESERI JAYA 柏斯里再也 BATU 9 JALAN KAKI BUKIT PERLIS 7 RC08 JALAN PEDANG 39 LORONG 1 BESAR (U) RPA BATU 16 巴登勿刹路 KAKI BUKIT 02200 PERLIS 8 RC09 KAMPUNG BARU, 115 JALAN PASAR BARU KAKI BUKIT D/A KOPERASI 加基武吉甘光峇汝 PEKEBUN-PEKEBUN KECIL KAKI -

Giving Your Capability the Edge

6/2019 NORWEGIAN DEFENCE And SECURITY IndUSTRIES AssOCIATION Giving your capability the edge. Contribution to situational awareness Support for surfacing decision Proven ESM system combining the advantages of R-ESM and C-ESM Learn more at saab.no © thyssenkrupp Marine Systems Saab_0249_Submarine_annons_210x297.indd 1 2019-01-11 08:47 CAONTENTSRTIKKEL CONTENTS: HX PROGRAM Editor-in-Chief: 2 Five contenders for the Finland´s next fighter M.Sc. Bjørn Domaas Josefsen Poland buys F-35 SPACE TECHNOLOGY 5 NAMMO believes in hybrid rocket motors EUROPE NEEDS TO BOOST THEIR DEFENCE BUDGETS, REGARDLESS OF FSI WHO WINS THIS FALL’S PRESIDENTIAL 7 Norwegian Defence and Security industries ELECTION IN THE USA association The Munich Security Conference 2020 held in February clearly showed BULLETIN BOARD FOR DEFENCE, that security policy has become much more of a challenge. Not least, INDUSTRY AND TRADE the relations between the USA and the NATO countries in Europe have 17 Remote Weapons Stations to Switzerland taken on a new order of complexity. 18 Hycopter Hydrogen-Electric UAV Virtually every POTUS since the 1970’s has said that Europe needs to carry a greater part of the financial defence burden of the 20 51 “K9 Thunder” to the Indian Army NATO alliance. And even though Donald Trump has “modernised” the 19 No Bradley replacement diplomatic language to quite an extent, the key message remains the 21 Gremlins program 1st Flight Test for X-61A Vehicle same. That said, many of the European nations have demonstrated 24 Germany needs a bigger and stronger Army reluctance to achieve the NATO goal of defence budgets to the tune of 25 South Korea and Poland into joint tank development? 2 % of the gross national product by 2024.