Levelling and Loudness — in Radio and Television Broadcasting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TS 101 499 V2.2.1 (2008-07) Technical Specification

ETSI TS 101 499 V2.2.1 (2008-07) Technical Specification Digital Audio Broadcasting (DAB); MOT SlideShow; User Application Specification European Broadcasting Union Union Européenne de Radio-Télévision EBU·UER 2 ETSI TS 101 499 V2.2.1 (2008-07) Reference RTS/JTC-DAB-57 Keywords audio, broadcasting, DAB, digital, PAD ETSI 650 Route des Lucioles F-06921 Sophia Antipolis Cedex - FRANCE Tel.: +33 4 92 94 42 00 Fax: +33 4 93 65 47 16 Siret N° 348 623 562 00017 - NAF 742 C Association à but non lucratif enregistrée à la Sous-Préfecture de Grasse (06) N° 7803/88 Important notice Individual copies of the present document can be downloaded from: http://www.etsi.org The present document may be made available in more than one electronic version or in print. In any case of existing or perceived difference in contents between such versions, the reference version is the Portable Document Format (PDF). In case of dispute, the reference shall be the printing on ETSI printers of the PDF version kept on a specific network drive within ETSI Secretariat. Users of the present document should be aware that the document may be subject to revision or change of status. Information on the current status of this and other ETSI documents is available at http://portal.etsi.org/tb/status/status.asp If you find errors in the present document, please send your comment to one of the following services: http://portal.etsi.org/chaircor/ETSI_support.asp Copyright Notification No part may be reproduced except as authorized by written permission. -

Model HR-ADC1 Analog to Digital Audio Converter

HALF-RACK SERIES Model HR-ADC1 Analog to Digital Audio Converter • Broadcast Quality Analog to Digital Audio Conversion • Peak Metering with Selectable Hold or Peak Store Modes • Inputs: Balanced and Unbalanced Stereo Audio • Operation Up to 24 bits, 192 kHz • Output: AES/EBU, Coaxial S/PDIF, AES-3ID • Selectable Internally Generated Sample Rate and Bit Depth • External Sync Inputs: AES/EBU, Coaxial S/PDIF, AES-3ID • Front-Panel External Sync Enable Selector and Indicator • Adjustable Audio Input Gain Trim • Sample Rate, Bit Depth, External Sync Lock Indicators • Peak or Average Ballistic Metering with Selectable 0 dB Reference • Transformer Isolated AES/EBU Output The HR-ADC1 is an RDL HALF-RACK product, featuring an all metal chassis and the advanced circuitry for which RDL products are known. HALF-RACKs may be operated free-standing using the included feet or may be conveniently rack mounted using available rack-mount adapters. APPLICATION: The HR-ADC1 is a broadcast quality A/D converter that provides exceptional audio accuracy and clarity with any audio source or style. Superior analog performance fine tuned through audiophile listening practices produces very low distortion (0.0006%), exceedingly low noise (-135 dB) and remarkably flat frequency response (+/- 0.05 dB). This performance is coupled with unparalleled metering flexibility and programmability with average mastering level monitoring and peak value storage. With external sync capability plus front-panel settings up to 24 bits and up to 192 kHz sample rate, the HR-ADC1 is the single instrument needed for A/D conversion in demanding applications. The HR-ADC1 accepts balanced +4 dBu or unbalanced -10 dBV stereo audio through rear-panel XLR or RCA jacks or through a detachable terminal block. -

PUBLIC VERSION AT&T Good Faith Complaint.Pdf

PUBLIC VERSION %HIRUH WKH )('(5$/ &20081,&$7,216 &200,66,21 :DVKLQJWRQ '& ',5(&79 //& $1' $7 7 6(59,&(6 ,1& &RPSODLQDQWV Y 0% 'RFNHW 1R )LOH 1RBBBBBBBBB '((5),(/' 0(',$ ,1& '((5),(/' 0(',$ 3257 $57+85 /,&(16(( //& (;3(',7(' '((5),(/' 0(',$ &,1&,11$7, /,&(16(( //& 75($70(17 '((5),(/' 0(',$ 02%,/( /,&(16(( //& 5(48(67(' '((5),(/' 0(',$ 52&+(67(5 /,&(16(( //& '((5),(/' 0(',$ 6$1 $1721,2 /,&(16(( //& *2&20 0(',$ 2) ,//,12,6 //& +2:$5' 67,5. +2/',1*6 //& +6+ )/,17 :(<, /,&(16(( //& +6+ 0<57/( %($&+ ::0% /,&(16(( //& 0(5&85< %52$'&$67,1* &203$1< ,1& 036 0(',$ 2) 7(11(66(( /,&(16(( //& 036 0(',$ 2) *$,1(69,//( /,&(16(( //& 036 0(',$ 2) 7$//$+$66(( /,&(16(( //& 036 0(',$ 2) 6&5$1721 /,&(16(( //& 1$6+9,//( /,&(16( +2/',1*6 //& .075 7(/(9,6,21 //& 6(&21' *(1(5$7,21 2) ,2:$ /7' $1' :$,77 %52$'&$67,1* ,1& 'HIHQGDQWV 9(5,),(' &203/$,17 2) ',5(&79 //& $1' $7 7 6(59,&(6 ,1& )25 7+( 67$7,21 *52836¶ )$,/85( 72 1(*27,$7( ,1 *22' )$,7+ PUBLIC VERSION 6HDQ $ /HY &DWK\ &DUSLQR .HYLQ - 0LOOHU &KULVWRSKHU 0 +HLPDQQ 0DWWKHZ 0 'XII\ *DU\ / 3KLOOLSV .(//2** +$16(1 72'' 'DYLG / /DZVRQ ),*(/ )5('(5,&. 3//& $7 7 6(59,&(6 ,1& 0 6WUHHW 1: 6XLWH WK 6WUHHW 1: 6XLWH :DVKLQJWRQ '& :DVKLQJWRQ '& Counsel for DIRECTV, LLC and AT&T Services, Inc. -XQH PUBLIC VERSION 6800$5< ,Q IODJUDQW YLRODWLRQ RI WKH &RPPLVVLRQ¶V UXOHV QLQH VWDWLRQ JURXSV WKH ³6WDWLRQ *URXSV´ KDYH VLPSO\ UHIXVHG WR QHJRWLDWH UHWUDQVPLVVLRQ FRQVHQW ZLWK ',5(&79 DQG $7 7 6HUYLFHV FROOHFWLYHO\ ³$7 7´ IRU PRQWKV RQ HQG ,QGHHG WKH 6WDWLRQ *URXSV HDFK RI ZKLFK DSSHDUV WR EH PDQDJHG DQG FRQWUROOHG -

Audio Engineering Society Convention Paper

Audio Engineering Society Convention Paper Presented at the 128th Convention 2010 May 22–25 London, UK The papers at this Convention have been selected on the basis of a submitted abstract and extended precis that have been peer reviewed by at least two qualified anonymous reviewers. This convention paper has been reproduced from the author's advance manuscript, without editing, corrections, or consideration by the Review Board. The AES takes no responsibility for the contents. Additional papers may be obtained by sending request and remittance to Audio Engineering Society, 60 East 42nd Street, New York, New York 10165-2520, USA; also see www.aes.org. All rights reserved. Reproduction of this paper, or any portion thereof, is not permitted without direct permission from the Journal of the Audio Engineering Society. Loudness Normalization In The Age Of Portable Media Players Martin Wolters1, Harald Mundt1, and Jeffrey Riedmiller2 1 Dolby Germany GmbH, Nuremberg, Germany [email protected], [email protected] 2 Dolby Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA [email protected] ABSTRACT In recent years, the increasing popularity of portable media devices among consumers has created new and unique audio challenges for content creators, distributors as well as device manufacturers. Many of the latest devices are capable of supporting a broad range of content types and media formats including those often associated with high quality (wider dynamic-range) experiences such as HDTV, Blu-ray or DVD. However, portable media devices are generally challenged in terms of maintaining consistent loudness and intelligibility across varying media and content types on either their internal speaker(s) and/or headphone outputs. -

Replacing Digital Terrestrial Television with Internet Protocol?

This is a repository copy of The short future of public broadcasting: Replacing digital terrestrial television with internet protocol?. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/94851/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Ala-Fossi, M and Lax, S orcid.org/0000-0003-3469-1594 (2016) The short future of public broadcasting: Replacing digital terrestrial television with internet protocol? International Communication Gazette, 78 (4). pp. 365-382. ISSN 1748-0485 https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048516632171 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ The Short Future of Public Broadcasting: Replacing DTT with IP? Marko Ala-Fossi & Stephen Lax School of Communication, School of Media and Communication Media and Theatre (CMT) University of Leeds 33014 University of Tampere Leeds LS2 9JT Finland UK [email protected] [email protected] Keywords: Public broadcasting, terrestrial television, switch-off, internet protocol, convergence, universal service, data traffic, spectrum scarcity, capacity crunch. -

A Brief History of Radio Broadcasting in Africa

A Brief History of Radio Broadcasting in Africa Radio is by far the dominant and most important mass medium in Africa. Its flexibility, low cost, and oral character meet Africa's situation very well. Yet radio is less developed in Africa than it is anywhere else. There are relatively few radio stations in each of Africa's 53 nations and fewer radio sets per head of population than anywhere else in the world. Radio remains the top medium in terms of the number of people that it reaches. Even though television has shown considerable growth (especially in the 1990s) and despite a widespread liberalization of the press over the same period, radio still outstrips both television and the press in reaching most people on the continent. The main exceptions to this ate in the far south, in South Africa, where television and the press are both very strong, and in the Arab north, where television is now the dominant medium. South of the Sahara and north of the Limpopo River, radio remains dominant at the start of the 21St century. The internet is developing fast, mainly in urban areas, but its growth is slowed considerably by the very low level of development of telephone systems. There is much variation between African countries in access to and use of radio. The weekly reach of radio ranges from about 50 percent of adults in the poorer countries to virtually everyone in the more developed ones. But even in some poor countries the reach of radio can be very high. In Tanzania, for example, nearly nine out of ten adults listen to radio in an average week. -

Mass Media in the USA»

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by BSU Digital Library Mass Media In The USA K. Khomtsova, V. Zavatskaya The topic of the research is «Mass media in the USA». It is topical because mass media of the United States are world-known and a lot of people use American mass media, especially internet resources. The subject matter is peculiarities of different types of mass media in the USA. The aim of the survey is to study the types of mass media that are popular in the USA nowadays. To achieve the aim the authors fulfill the following tasks: 1. to define the main types of mass media in the USA; 2. to analyze the popularity of different kinds of mass media in the USA; 3. to mark out the peculiarities of American mass media. The mass media are diversified media technologies that are intended to reach a large audience by mass communication. There are several types of mass media: the broadcast media such as radio, recorded music, film and tel- evision; the print media include newspapers, books and magazines; the out- door media comprise billboards, signs or placards; the digital media include both Internet and mobile mass communication. [4]. In the USA the main types of mass media today are: newspapers; magazines; radio; television; Internet. NEWSPAPERS The history of American newspapers goes back to the 17th century with the publication of the first colonial newspapers. It was James Franklin, Benjamin Franklin’s older brother, who first made a news sheet. -

AM / FM / DAB / XM Tuner

ENGLISH FRANÇAIS Owner’s Manual Owner’s ESPAÑOL ® ITALIANO AM / FM / DAB / XM Tuner /XM /DAB /FM AM M4 DEUTSCH NEDERLANDS SVENSKA РУССКИЙ IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS ENGLISH 1. Read instructions - All the safety and operating instructions should be NOTE TO CATV SYSTEM INSTALLER read before the product is operated. This reminder is provided to call the CATV system installer’s attention to Section 820-40 of 2. Retain instructions - The safety and operating instructions should be the NEC which provides guidelines for proper grounding and, in particular, specifies that retained for future reference. the cable ground shall be connected to the grounding system of the building, as close 3. Heed Warnings - All warnings on the product and in the operating to the point of cable entry as practical. instructions should be adhered to. 4. Follow Instructions - All operating and use instructions should be FRANÇAIS followed. 5. Cleaning - Unplug this product from the wall outlet before cleaning. Do not use liquid cleaners or aerosol cleaners. Use a damp cloth for cleaning. 6. Attachments - Do not use attachments not recommended by the product manufacturer as they may cause hazards. 7. Water and Moisture - Do not use this product near water-for example, near a bath tub, wash bowl, kitchen sink, or laundry tub; in a wet basement; or near a swimming pool; and the like. ESPAÑOL 8. Accessories - Do not place this product on an unstable cart, stand, tripod, bracket, or table. The product may fall, causing serious injury to a child or adult and serious damage to the product. Use only with a cart, stand, tripod, bracket, or table recommended by the manufacturer, or sold with the product. -

Digital Audio Broadcasting : Principles and Applications of Digital Radio

Digital Audio Broadcasting Principles and Applications of Digital Radio Second Edition Edited by WOLFGANG HOEG Berlin, Germany and THOMAS LAUTERBACH University of Applied Sciences, Nuernberg, Germany Digital Audio Broadcasting Digital Audio Broadcasting Principles and Applications of Digital Radio Second Edition Edited by WOLFGANG HOEG Berlin, Germany and THOMAS LAUTERBACH University of Applied Sciences, Nuernberg, Germany Copyright ß 2003 John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England Telephone (þ44) 1243 779777 Email (for orders and customer service enquiries): [email protected] Visit our Home Page on www.wileyeurope.com or www.wiley.com All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England, or emailed to [email protected], or faxed to (þ44) 1243 770571. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the Publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. -

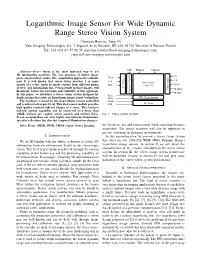

Logarithmic Image Sensor for Wide Dynamic Range Stereo Vision System

Logarithmic Image Sensor For Wide Dynamic Range Stereo Vision System Christian Bouvier, Yang Ni New Imaging Technologies SA, 1 Impasse de la Noisette, BP 426, 91370 Verrieres le Buisson France Tel: +33 (0)1 64 47 88 58 [email protected], [email protected] NEG PIXbias COLbias Abstract—Stereo vision is the most universal way to get 3D information passively. The fast progress of digital image G1 processing hardware makes this computation approach realizable Vsync G2 Vck now. It is well known that stereo vision matches 2 or more Control Amp Pixel Array - Scan Offset images of a scene, taken by image sensors from different points RST - 1280x720 of view. Any information loss, even partially in those images, will V Video Out1 drastically reduce the precision and reliability of this approach. Exposure Out2 In this paper, we introduce a stereo vision system designed for RD1 depth sensing that relies on logarithmic image sensor technology. RD2 FPN Compensation The hardware is based on dual logarithmic sensors controlled Hsync and synchronized at pixel level. This dual sensor module provides Hck H - Scan high quality contrast indexed images of a scene. This contrast indexed sensing capability can be conserved over more than 140dB without any explicit sensor control and without delay. Fig. 1. Sensor general structure. It can accommodate not only highly non-uniform illumination, specular reflections but also fast temporal illumination changes. Index Terms—HDR, WDR, CMOS sensor, Stereo Imaging. the details are lost and consequently depth extraction becomes impossible. The sensor reactivity will also be important to prevent saturation in changing environments. -

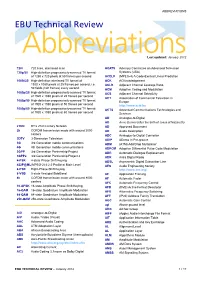

ABBREVIATIONS EBU Technical Review

ABBREVIATIONS EBU Technical Review AbbreviationsLast updated: January 2012 720i 720 lines, interlaced scan ACATS Advisory Committee on Advanced Television 720p/50 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format Systems (USA) of 1280 x 720 pixels at 50 frames per second ACELP (MPEG-4) A Code-Excited Linear Prediction 1080i/25 High-definition interlaced TV format of ACK ACKnowledgement 1920 x 1080 pixels at 25 frames per second, i.e. ACLR Adjacent Channel Leakage Ratio 50 fields (half frames) every second ACM Adaptive Coding and Modulation 1080p/25 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format ACS Adjacent Channel Selectivity of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 25 frames per second ACT Association of Commercial Television in 1080p/50 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format Europe of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 50 frames per second http://www.acte.be 1080p/60 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format ACTS Advanced Communications Technologies and of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 60 frames per second Services AD Analogue-to-Digital AD Anno Domini (after the birth of Jesus of Nazareth) 21CN BT’s 21st Century Network AD Approved Document 2k COFDM transmission mode with around 2000 AD Audio Description carriers ADC Analogue-to-Digital Converter 3DTV 3-Dimension Television ADIP ADress In Pre-groove 3G 3rd Generation mobile communications ADM (ATM) Add/Drop Multiplexer 4G 4th Generation mobile communications ADPCM Adaptive Differential Pulse Code Modulation 3GPP 3rd Generation Partnership Project ADR Automatic Dialogue Replacement 3GPP2 3rd Generation Partnership -

Receiver Dynamic Range: Part 2

The Communications Edge™ Tech-note Author: Robert E. Watson Receiver Dynamic Range: Part 2 Part 1 of this article reviews receiver mea- the receiver can process acceptably. In sim- NF is the receiver noise figure in dB surements which, taken as a group, describe plest terms, it is the difference in dB This dynamic range definition has the receiver dynamic range. Part 2 introduces between the inband 1-dB compression point advantage of being relatively easy to measure comprehensive measurements that attempt and the minimum-receivable signal level. without ambiguity but, unfortunately, it to characterize a receiver’s dynamic range as The compression point is obvious enough; assumes that the receiver has only a single a single number. however, the minimum-receivable signal signal at its input and that the signal is must be identified. desired. For deep-space receivers, this may be COMPREHENSIVE MEASURE- a reasonable assumption, but the terrestrial MENTS There are a number of candidates for mini- mum-receivable signal level, including: sphere is not usually so benign. For specifi- The following receiver measurements and “minimum-discernable signal” (MDS), tan- cation of general-purpose receivers, some specifications attempt to define overall gential sensitivity, 10-dB SNR, and receiver interfering signals must be assumed, and this receiver dynamic range as a single number noise floor. Both MDS and tangential sensi- is what the other definitions of receiver which can be used both to predict overall tivity are based on subjective judgments of dynamic range do. receiver performance and as a figure of merit signal strength, which differ significantly to compare competing receivers.