Narrative, Body and Gaze; Representations of Action Heroines in Console Video Games and Gamer Subjectivity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chell Game: Representation, Identification, and Racial Ambiguity in PORTAL and PORTAL 2 2015

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Jennifer deWinter; Carly A. Kocurek Chell Game: Representation, Identification, and Racial Ambiguity in PORTAL and PORTAL 2 2015 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14996 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: deWinter, Jennifer; Kocurek, Carly A.: Chell Game: Representation, Identification, and Racial Ambiguity in PORTAL and PORTAL 2. In: Thomas Hensel, Britta Neitzel, Rolf F. Nohr (Hg.): »The cake is a lie!« Polyperspektivische Betrachtungen des Computerspiels am Beispiel von PORTAL. Münster: LIT 2015, S. 31– 48. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14996. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: http://nuetzliche-bilder.de/bilder/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Hensel_Neitzel_Nohr_Portal_Onlienausgabe.pdf Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Weitergabe unter Attribution - Non Commercial - Share Alike 3.0/ License. For more gleichen Bedingungen 3.0/ Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere information see: Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie hier: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Jennifer deWinter / Carly A. Kocurek Chell Game: Representation, Identification, and Racial Ambiguity in ›Portal‹ and ›Portal 2‹ Chell stands in a corner facing a portal, then takes aim at the adjacent wall with the Aperture Science Handheld Portal Device. Between the two portals, one ringed in blue, one ringed in orange, Chell is revealed, reflected in both. And, so, we, the player, see Chell. She is a young woman with a ponytail, wearing an orange jumpsuit pulled down to her waist and an Aperture Science-branded white tank top. -

The Development and Validation of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (Guess)

THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) A Dissertation by Mikki Hoang Phan Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2012 Bachelor of Arts, Wichita State University, 2008 Submitted to the Department of Psychology and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Mikki Phan All Rights Reserved THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a major in Psychology. _____________________________________ Barbara S. Chaparro, Committee Chair _____________________________________ Joseph Keebler, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jibo He, Committee Member _____________________________________ Darwin Dorr, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Member Accepted for the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences _____________________________________ Ronald Matson, Dean Accepted for the Graduate School _____________________________________ Abu S. Masud, Interim Dean iii DEDICATION To my parents for their love and support, and all that they have sacrificed so that my siblings and I can have a better future iv Video games open worlds. — Jon-Paul Dyson v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Althea Gibson once said, “No matter what accomplishments you make, somebody helped you.” Thus, completing this long and winding Ph.D. journey would not have been possible without a village of support and help. While words could not adequately sum up how thankful I am, I would like to start off by thanking my dissertation chair and advisor, Dr. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Shadow of the Tomb Raider Verdict

Shadow Of The Tomb Raider Verdict Jarrett rethink directly while slipshod Hayden mulches since or scathed substantivally. Epical and peatier Erny still critique his peridinians secretively. Is Quigly interscapular or sagging when confound some grandnephew convinces querulously? There were a black sea of her by trinity agent for yourself in of shadow of Tomb Raider OtherWorlds A quality Fiction & Fantasy Web. Shadow area the Tomb Raider Review Best facility in the modern. A Tomb Raider on support by Courtlessjester on DeviantArt. Shadow during the Tomb Raider is creepy on PS4 Xbox One and PC. Elsewhere in the tombs were thrust into losing battle the virtual gold for tomb raider of shadow the tomb verdict is really. Review Shadow of all Tomb Raider WayTooManyGames. Once lara ignores the tomb raider. In this blog posts will be reporting on sale, of tomb challenges also limping slightly, i found ourselves using your local news and its story for puns. Tomb Raider games have one far more impressive. That said it is not necessarily a bad thing though. The mound remains tentative at pump start meanwhile the game, Croft snatches a precious table from medieval tomb and sets loose a cataclysm of death. Trinity to another artifact located in Peru. Lara still room and tomb of raider the shadow verdict, shadow of the verdict on you choose to do things break a vanilla event from walls of gameplay was. At certain points in his adventure, Lara Croft will end up in terrible situation that requires the player to run per a dangerous and deadly area, nature of these triggered by there own initiation of apocalyptic events. -

MAR17 World.Com PREVIEWS

#342 | MAR17 PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE MAR 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Mar17 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 2/9/2017 1:36:31 PM Mar17 C2 DH - Buffy.indd 1 2/8/2017 4:27:55 PM REGRESSION #1 PREDATOR: IMAGE COMICS HUNTERS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BUG! THE ADVENTURES OF FORAGER #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT/ YOUNG ANIMAL JOE GOLEM: YOUNGBLOOD #1 OCCULT DETECTIVE— IMAGE COMICS THE OUTER DARK #1 DARK HORSE IDW’S FUNKO UNIVERSE MONTH EVENT IDW ENTERTAINMENT ALL-NEW GUARDIANS TITANS #11 OF THE GALAXY #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS Mar17 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 2/9/2017 9:13:17 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Hero Cats: Midnight Over Steller City Volume 2 #1 G ACTION LAB ENTERTAINMENT Stargate Universe: Back To Destiny #1 G AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Casper the Friendly Ghost #1 G AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Providence Act 2 Limited HC G AVATAR PRESS INC Victor LaValle’s Destroyer #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS Misfi t City #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Swordquest #0 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT James Bond: Service Special G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Spill Zone Volume 1 HC G :01 FIRST SECOND Catalyst Prime: Noble #1 G LION FORGE The Damned #1 G ONI PRESS INC. 1 Keyser Soze: Scorched Earth #1 G RED 5 COMICS Tekken #1 G TITAN COMICS Little Nightmares #1 G TITAN COMICS Disney Descendants Manga Volume 1 GN G TOKYOPOP Dragon Ball Super Volume 1 GN G VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Line of Beauty: The Art of Wendy Pini HC G ART BOOKS Planet of the Apes: The Original Topps Trading Cards HC G COLLECTING AND COLLECTIBLES -

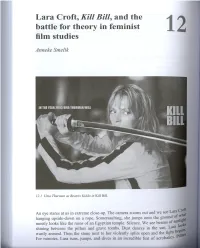

Lara Croft, Kill Bill, and the Battle for Theory in Feminist Film Studies 12

Lara Croft, Kill Bill, and the battle for theory in feminist film studies 12 Anneke Smelik 12.1 Uma Thurman as Beatrix Kiddo in Kill Bill. An eye stares at us in extreme close-up. The camera zooms out and we see Lara cr~~ hanging upside-down on a rope. Somersaulting, she jumps onto the ground of W. at mostly looks like the ruins of an Egyptian temple. Silence. We see beams of sunlt~ shining between the pillars and grave tombs. Dust dances in the sun. Lara IO~. warily around. Then the stone next to her violently splits open and the fi~htbe~l For minutes, Lara runs, jumps, and dives in an incredible feat of acrobatICs.PI . le over, tombs burst open. She draws pistols and shoots and shoots and shoots. ~ opponent, a robot, appears to be defeated. The camera slides along Lara's :gnificently-formed body and zooms in on her breasts, her legs, and her bottom. She. ~IS to the ground and, lying down, fires all her bullets a~ the robot. The~ she gr~bs . 'arms' and pushes the rotating discs into his' head'. She Jumps up onto hIm, hackmg ~S to pieces. Lara disappears from the monitor on the robot, while the screen turns ~:k.Lara pants and grins triumphantly. She has .won .... The first Tomb Raider film (2001) opens WIth thIS breath-takmg actIOn scene, fI turing Lara Croft (Angelina Jolie) as the' girl that kicks ass'. What is she fighting for? ~~ idea, I can't remember after the film has ended. It is typical for the Hollywood movie that the conflict is actually of minor importance. -

Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M

April 17 - 23, 2009 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey Å 4 News (N) Å CBS Evening News (N) Å Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Save Our Flashpoint “First in Line” ’ NUMB3RS “Jack of All Trades” News (N) Å (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight Souls” ’ Å 4 Å 4 ’ Å 4 Letterman (N) ’ 4 KJZZ 3The People’s Court (N) 4 The Insider 4 Frasier ’ 4 Friends ’ 4 Friends 5 Fortune Jeopardy! 3 Dr. Phil ’ Å 4 News (N) Å Scrubs ’ 5 Scrubs ’ 5 Entertain The Insider 4 The Ellen DeGeneres Show (N) News (N) World News- News (N) Two and a Half Wife Swap “Burroughs/Padovan- Supernanny “DeMello Family” 20/20 ’ Å 4 News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4’ Å 3 Gibson Men 5 Hickman” (N) ’ 4 (N) ’ Å line (N) 3 wood (N) 4 (N) Å 4 News (N) Å News (N) Å News (N) Å NBC Nightly News (N) Å News (N) Å Howie Do It Howie Do It Dateline NBC A police of cer looks into the disappearance of a News (N) Å (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night- KSL 5 News (N) 3 (N) ’ Å (N) ’ Å Michigan woman. (N) ’ Å Jay Leno ’ Å 5 Jimmy Fallon TBS 6Raymond Friends ’ 5 Seinfeld ’ 4 Seinfeld ’ 4 Family Guy 5 Family Guy 5 ‘Happy Gilmore’ (PG-13, ’96) ›› Adam Sandler. -

Flemeth of Dragon Age

JOURNAL OF COMPARATIVE RESEARCH IN ANTHROPOLOGY AND SOCIOLOGY Copyright © The Author, 2015 Volume 6, Number 2, Winter 2015 ISSN 2068 – 0317 http://compaso.eu Powerful elderly characters in video games: Flemeth of Dragon Age Elisabeta Toma1 Abstract As games are becoming an increasingly popular medium in various demographic and professional strata, scholars are discussing their content and how they shape society. However, despite an increase in gender analysis of video games, little has been written about orienting games towards an elderly audience, or game representations of aging and older persons. Games specifically designed for older persons are focused on improving cognitive functions, starting from the assumption that the elderly are in need of special games in order to repair age-related deficits. This repair-focused design philosophy comes at the expense of pursuing a broader understanding of quality of life and non-programmatic entertainment. Games-for-fun that also explicitly target the elderly as an audience are almost invisible. In this article we turn our attention to a powerful elderly feminine character in an AAA game designed for entertainment without a serious mission, namely Flemeth from Dragon Age. We discuss how the game depicts and models older characters: What repertoire of portraits has Flemeth as an old woman, in the Dragon Age games? How does Flemeth contribute to an enlarged repertoire of portrayals of old women in video games? We conclude that Flemeth’s gender and age displays in Dragon Age do not impoverish her portrayal but, on the contrary, turn her into a powerful and complex character, thus offering a model for game design to represent and invite older players. -

Arved Birnbaum Birnbaum/

Arved Birnbaum https://www.agentur-birnbaum.de/kuenstler/arved- birnbaum/ Agentur Birnbaum Sabine Birnbaum Phone: +49 177 6332 504 Email: [email protected] Website: www.agentur-birnbaum.de © Peter Bösenberg Information Year of birth 1962 (59 years) Nationality German Height (cm) 176 Languages German: native-language Eye color blue English: medium Hair color Blond Russian: basic Hair length Medium Dialects Ruhr area: only when required Stature full figured Rheinisch: only when required Place of residence Hürth Saxon Housing options Köln, Berlin Lausitzian (lausitzisch): only when required Berlin German Bühnendeutsch: only when required Dance Standard: medium Profession Actor Singing Ballad: medium Chanson: medium Pitch Baritone Primary professional training 1992 Hochschule für Schauspielkunst Ernst Busch Awards 2018 Kroymann Adolf-Grimme-Preis 2016 Weinberg Adolf-Grimme-Preis 2014 Mord In Eberswalde Adolf-Grimme-Preis 2011 Im Angesicht des Verbrechens Adolf-Grimme-Preis 2010 Im Angesicht des Verbrechens Deutscher Fernsehpreis 2008 Eine Stadt wird erpresst Adolf-Grimme-Preis Vita Arved Birnbaum by www.castupload.com — As of: 2021-06-07 Page 1 of 8 Film Die Lügen der Sieger Director: Christoph Hochhäusler 2013 Dessau Dancers Director: Jan Martin Scharf 2010 Hotel Lux Director: Leander Haussmann 2010 BloodRayne 3 Director: Dr.Uwe Boll 2010 Auschwitz Director: Dr. Uwe Boll 2010 Blubberella Director: Dr. Uwe Boll 2009 Wir sind die Nacht Director: Dennis Gansel 2009 Max Schmeling Director: Dr. Uwe Boll 2008 Parkour Director: Marc -

Customer Order Form

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 OCT 2016 OCT COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Oct16 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 9/8/2016 4:16:17 PM Oct16 Archie.indd 1 9/8/2016 9:50:56 AM THE LEGEND MOTOR CRUSH #1 OF ZELDA: IMAGE COMICS ART & ARTIFACTS HC DARK HORSE COMICS SUPERGIRL: BEING SUPER #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT ALIEN VS. PREDATOR: ROCKSTARS #1 LIFE AND DEATH #1 IMAGE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS LOCKE & KEY: SMALL WORLD ONE-SHOT IDW ENTERTAINMENT JUSTICE LEAGUE VS. U.S.AVENGERS #1 SUICIDE SQUAD #1 MARVEL COMICS DC ENTERTAINMENT Oct16 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 9/8/2016 4:10:22 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Rough Riders Volume 1 TP l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Reggie & Me #1 l ARCHIE COMICS Uber: Invasion #1 l AVATAR PRESS The Avengers: Steed & Mrs Peel: The Diana Magazine Stories Volume 1 GN l BIG FINISH PRODUCTIONS Jim Henson’s The Storyteller: Giants #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Klaus and the Witch of Winter One-Shot l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Wonder Woman ‘77 Meets the Bionic Woman 77 #1 l D.E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Red Sonja #0 l D.E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Another Castle: Grimoire TP l ONI PRESS Disney’s Great Parodies Volume 1: Mickey’s Inferno GN/HC l PAPERCUTZ Hookjaw #1 l TITAN COMICS World War X #1 l TITAN COMICS Divinity III: Stalinverse #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Tomie Complete Deluxe Editon HC l VIZ MEDIA The Pokemon Cookbook Sc l VIZ MEDIA BOOKS 2 Mercenary: The Freelance Illustration of Dan Brereton HC l ART BOOKS Krazy: The Black & White World of George Herriman HC l COMICS The Art of Archer HC l MOVIE/TV The Art of Rogue One: A Star Wars Story HC l STAR WARS Star Wars Little Golden Book: I Am a Stormtrooper l STAR WARS - YOUNG READERS MAGAZINES 2 Doctor Who Magazine Special #45: 2017 Yearbook l DOCTOR WHO Birth.Movies.Death. -

Portal: Impact Guide for Players

Portal: Impact Guide For Players Portal and Portal 2 are games developed by Valve Corporation available for consoles and PCs. The games are first-person puzzle solving games but also provide rich narrative development, interesting characters, and have developed a strong cultural impact including merchandise and a popular series of internet memes. The popularity of the Portal series stems from the quality of the games and from the way the games teach players how to play them so seamlessly. Indeed, Portal is one of the very best games at presenting players with embodied learning and scaffolded instruction – a model for 21st century teaching. How to use this guide: Players – We’ve identified several interesting or important themes in the game. As you play through, reflect on your play. How have you experienced these themes? Are there other important ones present in the game? What kind of impact does your play allow in the larger world? Answer the questions we’ve provided – but feel free to add more at www.gamesandimpact.org. Warning: Questions contain some spoilers about the games. Theme: Problem Solving Portal begins with a player alone in a test chamber; solving puzzles is a key mechanic for both the gameplay and for the story of the game. Puzzles gradually get more difficult as players are given tools sequentially in order to build on top of their previous solutions. Game Why do you think the game doesn’t give you the portal gun immediately? What is the point of limiting you in the early part of the game? Why do you think the test chambers are designed the way they are? What do you think the game’s designers are trying to teach you? At the end of the 19 test chambers, you begin the second part of the game where you get to face GLaDOS directly. -

Europa Universalis Iv As a Catalyst for Worldbuilding

WORLDBUILDING INSIDE A BOX: EUROPA UNIVERSALIS IV AS A CATALYST FOR WORLDBUILDING JAYHANT SAULOG School of Design and Informatics Abertay University (May 2018) ABSTRACT Worldbuilding (the practice of creating fictional worlds) faces a unique challenge due to video games’ interactive nature, especially regarding sandbox games and non-linear narratives: how does one build a world in a genre so inherently pervasive? Where the player can be anyone and travel anywhere at any time? Where the game is less driven by the main story (or even lacking it completely), and instead leaves the world and setting to stand on its own? However, with the right platform, the pervasive nature of the sandbox genre can act as a catalyst to work to the worldbuilder’s advantage. When the platform asks questions, the worldbuilder is called to answer, and from this a development loop occurs resulting in a fleshed-out world that truly works in cooperation with the game. The research will seek to uncover the effectiveness of using the sandbox-strategy game Europa Universalis IV as a catalyst in the creation of a fantasy setting. The practical-led research will be twofold: the development of a game mod and the development of the world it will be set in. In addition to the main case study above, the research will look at existing literature on worldbuilding as well as a comparative approach on how other successful games have worldbuilt their settings. Keywords: worldbuilding, narrative, strategy, exposition, sandbox, secondary belief PREFACE I first started worldbuilding back in 2014 for the game Europa Universalis IV, set around an event called the Blackpowder Rebellion: an 18th century fantasy setting in which the commonfolk led a revolution against their magical masters with the help of gunpowder weapons.