The German Intellectual's Adjustment to National Socialism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How the Luftwaffe Lost the Battle of Britain British Courage and Capability Might Not Have Been Enough to Win; German Mistakes Were Also Key

How the Luftwaffe Lost the Battle of Britain British courage and capability might not have been enough to win; German mistakes were also key. By John T. Correll n July 1940, the situation looked “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall can do more than delay the result.” Gen. dire for Great Britain. It had taken fight on the landing grounds, we shall Maxime Weygand, commander in chief Germany less than two months to fight in the fields and in the streets, we of French military forces until France’s invade and conquer most of Western shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender, predicted, “In three weeks, IEurope. The fast-moving German Army, surrender.” England will have her neck wrung like supported by panzers and Stuka dive Not everyone agreed with Churchill. a chicken.” bombers, overwhelmed the Netherlands Appeasement and defeatism were rife in Thus it was that the events of July 10 and Belgium in a matter of days. France, the British Foreign Office. The Foreign through Oct. 31—known to history as the which had 114 divisions and outnumbered Secretary, Lord Halifax, believed that Battle of Britain—came as a surprise to the Germany in tanks and artillery, held out a Britain had lost already. To Churchill’s prophets of doom. Britain won. The RAF little longer but surrendered on June 22. fury, the undersecretary of state for for- proved to be a better combat force than Britain was fortunate to have extracted its eign affairs, Richard A. “Rab” Butler, told the Luftwaffe in almost every respect. -

Mr. Booth World History 10 Introduction

World War II Mr. Booth World History 10 Introduction: • Most devastating war in human history • 55 million dead • 1 trillion dollars • Began in 1939 as strictly a European Conflict, ended in 1945. • Widened to include most of the world Great Depression Leads Towards Fascism • In 1929, the U.S. Stock Market crashed and sent shockwaves throughout the world. • Many democracies, including the U.S., Britain, and France, remained strong despite the economic crisis caused by the G.D. • Millions lost faith in government • As a result, a few countries turned towards an extreme government called fascism. 1.Germany Adolf Hitler, 2.Spain Francisco Franco 3. Soviet Union Joseph Stalin 4. Italy Benito Mussolini Fascism • Fascism: A political movement that promotes an extreme form of nationalism, a denial of individual rights, and a dictatorial one-party rule. • Emphasizes 1) loyalty to the state, and 2) obedience to its leader. • Fascists promised to revive the economy, punish those responsible for hard times, and restore national pride. The Rise of Benito Mussolini • Fascism’s rise in Italy due to: • Disappointment over failure to win land at the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. • Italy wanted a leader who could take action Mussolini Background • Was a newspaper editor and politician • Said he would rebuild the economy, the armed forces, and give Italy a strong leadership. • Mussolini was able to come to power by – publicly criticizing Italy’s government – Followers (black shirts) attacked communists and socialists on the streets. • In October 1922 • 30,000 followers marched to Rome and demanded that King Victor Emmanuel III put Mussolini in charge Il Duce Fist Pump 3 Decisions he made for complete control • Mussolini was Il Duce, or the leader. -

Nazi Germany and the Jews Ch 3.Pdf

AND THE o/ w VOLUME I The Years of Persecution, i933~i939 SAUL FRIEDLANDER HarperCollinsPííMí^ers 72 • THE YEARS OF PERSECUTION, 1933-1939 dependent upon a specific initial conception and a visible direction. Such a CHAPTER 3 conception can be right or wrong; it is the starting point for the attitude to be taken toward all manifestations and occurrences of life and thereby a compelling and obligatory rule for all action."'^'In other words a worldview as defined by Hitler was a quasi-religious framework encompassing imme Redemptive Anti-Semitism diate political goals. Nazism was no mere ideological discourse; it was a political religion commanding the total commitment owed to a religious faith."® The "visible direction" of a worldview implied the existence of "final goals" that, their general and hazy formulation notwithstanding, were sup posed to guide the elaboration and implementation of short-term plans. Before the fall of 1935 Hitler did not hint either in public or in private I what the final goal of his anti-Jewish policy might be. But much earlier, as On the afternoon of November 9,1918, Albert Ballin, the Jewish owner of a fledgling political agitator, he had defined the goal of a systematic anti- the Hamburg-Amerika shipping line, took his life. Germany had lost the Jewish policy in his notorious first pohtical text, the letter on the "Jewish war, and the Kaiser, who had befriended him and valued his advice, had question" addressed on September 16,1919, to one Adolf Gemlich. In the been compelled to abdicate and flee to Holland, while in Berlin a republic short term the Jews had to be deprived of their civil rights: "The final aim was proclaimed. -

Lesson 12: Handout 4, Document 1 German Youth in the 1930S: Selected Excerpted Documents

Lesson 12: Handout 4, Document 1 German Youth in the 1930s: Selected excerpted documents Changes at School (Excerpted from “Changes at School,” pp. 175–76 in Facing History and Ourselves: Holocaust and Human Behavior ) Ellen Switzer, a student in Nazi Germany, recalls how her friend Ruth responded to Nazi antisemitic propaganda: Ruth was a totally dedicated Nazi. Some of us . often asked her how she could possibly have friends who were Jews or who had a Jewish background, when everything she read and distributed seemed to breathe hate against us and our ancestors. “Of course, they don’t mean you,” she would explain earnestly. “You are a good German. It’s those other Jews . who betrayed Germany that Hitler wants to remove from influence.” When Hitler actually came to power and the word went out that students of Jewish background were to be isolated, that “Aryan” Germans were no longer to associate with “non-Aryans” . Ruth actually came around and apologized to those of us to whom she was no longer able to talk. Not only did she no longer speak to the suddenly ostracized group of class - mates, she carefully noted down anybody who did, and reported them. 12 Purpose: To deepen understanding of how propaganda and conformity influence decision-making. • 186 Lesson 12: Handout 4, Document 2 German Youth in the 1930s: Selected excerpted documents Propaganda and Education (Excerpted from “Propaganda and Education,” pp. 242 –43 in Facing History and Ourselves: Holocaust and Human Behavior ) In Education for Death , American educator Gregor Ziemer described school - ing in Nazi Germany: A teacher is not spoken of as a teacher ( Lehrer ) but an Erzieher . -

The Development and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Isdap Electoral Breakthrough

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1976 The evelopmeD nt and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Nsdap Electoral Breakthrough. Thomas Wiles Arafe Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Arafe, Thomas Wiles Jr, "The eD velopment and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Nsdap Electoral Breakthrough." (1976). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2909. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2909 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. « The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing pega(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Nietzsche's Jewish Problem: Between Anti-Semitism and Anti-Judaism

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. CHAPTER ONE The Rise and Fall of Nietzschean Anti- Semitism REACTIONS OF ANTI- SEMITES PRIOR TO 1900 Discussions and remarks about Jews and Judaism can be found throughout Nietzsche’s writings, from the juvenilia and early letters until the very end of his sane existence. But his association with anti-Semitism during his life- time culminates in the latter part of the 1880s, when Theodor Fritsch, the editor of the Anti- Semitic Correspondence, contacted him. Known widely in the twentieth century for his Anti- Semites’ Catechism (1887), which appeared in forty- nine editions by the end of the Second World War, Fritsch wrote to Nietz sche in March 1887, assuming that he harbored similar views toward the Jews, or at least that he was open to recruitment for his cause.1 We will have an opportunity to return to this episode in chapter five, but we should observe that although Fritsch erred in his assumption, from the evidence he and the German public possessed at the time, he had more than sufficient reason to consider Nietzsche a like- minded thinker. First, in 1887 Nietzsche was still associated with Richard Wagner and the large circle of Wagnerians, whose ideology contained obvious anti- Semitic tendencies. Nietzsche’s last published work on Wagner, the deceptive encomium Richard Wagner in Bayreuth (1876), may contain the seeds of Nietzsche’s later criticism of the composer, but when it was published, it was regarded as celebratory and a sign of Nietzsche’s continued allegiance to the Wagnerian cultural move- ment. -

Jürgen Habermas and the Third Reich Max Schiller Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2012 Jürgen Habermas and the Third Reich Max Schiller Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Schiller, Max, "Jürgen Habermas and the Third Reich" (2012). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 358. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/358 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Introduction The formation and subsequent actions of the Nazi government left a devastating and indelible impact on Europe and the world. In the midst of general technological and social progress that has occurred in Europe since the Enlightenment, the Nazis represent one of the greatest social regressions that has occurred in the modern world. Despite the development of a generally more humanitarian and socially progressive conditions in the western world over the past several hundred years, the Nazis instigated one of the most diabolic and genocidal programs known to man. And they did so using modern technologies in an expression of what historian Jeffrey Herf calls “reactionary modernism.” The idea, according to Herf is that, “Before and after the Nazi seizure of power, an important current within conservative and subsequently Nazi ideology was a reconciliation between the antimodernist, romantic, and irrantionalist ideas present in German nationalism and the most obvious manifestation of means ...modern technology.” 1 Nazi crimes were so extreme and barbaric precisely because they incorporated modern technologies into a process that violated modern ethical standards. Nazi crimes in the context of contemporary notions of ethics are almost inconceivable. -

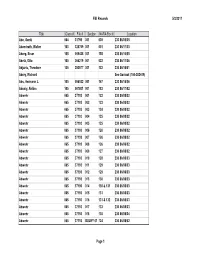

5/3/2011 FBI Records Page 1 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box

FBI Records 5/3/2011 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box # Location Abe, Genki 064 31798 001 039 230 86/05/05 Abendroth, Walter 100 325769 001 001 230 86/11/03 Aberg, Einar 105 009428 001 155 230 86/16/05 Abetz, Otto 100 004219 001 022 230 86/11/06 Abjanic, Theodore 105 253577 001 132 230 86/16/01 Abrey, Richard See Sovloot (100-382419) Abs, Hermann J. 105 056532 001 167 230 86/16/06 Abualy, Aldina 105 007801 001 183 230 86/17/02 Abwehr 065 37193 001 122 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 002 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 003 124 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 004 125 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 005 125 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 006 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 007 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 008 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 009 127 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 010 128 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 011 129 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 012 129 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 013 130 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 014 130 & 131 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 015 131 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 016 131 & 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 017 133 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 018 135 230 86/08/04 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 01 124 230 86/08/02 Page 1 FBI Records 5/3/2011 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box # Location Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 20 127 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 133 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 35 134 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 EBF 014X 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 EBF 014X 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr -

Modern History

MODERN HISTORY The Role of Youth Organisations in Nazi Germany: 1933-1939 It is often believed that children and adolescents are the most impressionable and vulnerable in society. Unlike adults, who have already developed their own established social views and political opinions, juveniles are still in the process of forming their attitudes and judgements on the world around them, so can easily be manipulated into following certain ideas and principles. This has been a fact widely taken advantage of by governments and political parties throughout history, in particular, by the Nazi Party under Adolf Hitler’s leadership between 1933 and 1939. The beginning of the 1930’s ushered in a new period of instability and uncertainty throughout Germany and with the slow but eventual collapse of the Weimar Government, as well as the start of the Great Depression, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) took the opportunity to gain a large and devoted following. This committed and loyal support was gained by appealing primarily to the industrial working class and the rural and farming communities, under the tenacious direction of nationalist politician Adolf Hitler. Through the use of powerful and persuasive propaganda, the Nazis presented themselves as ‘the party above class interests’1, a representation of hope, prosperity and unyielding leadership for the masses of struggling Germans. The appointment of NSDAP leader, Adolf Hitler, as chancellor of Germany on January 30th 1933, further cemented his reputation as the strong figure of guidance Germany needed to progress and prosper. On March 23rd 1933, the ‘Enabling Act’ was passed by a two thirds majority in the Reichstag, resulting in the suspension of the German Constitution and the rise of Hitler’s dictatorship. -

Upholding the Disney Utopia Through American Tragedy: a Study of the Walt Disney Company’S Responses to Pearl Harbor and 9/11

Upholding the Disney Utopia Through American Tragedy: A Study of The Walt Disney Company's Responses to Pearl Harbor and 9/11 Lindsay Goddard Senior Thesis presented to the faculty of the American Studies Department at the University of California, Davis March 2021 Abstract Since its founding in October 1923, The Walt Disney Company has en- dured as an influential preserver of fantasy, traditional American values, and folklore. As a company created to entertain the masses, its films often provide a sense of escapism as well as feelings of nostalgia. The company preserves these sentiments by \Disneyfying" danger in its media to shield viewers from harsh realities. Disneyfication is also utilized in the company's responses to cultural shocks and tragedies as it must carefully navigate maintaining its family-friendly reputation, utopian ideals, and financial interests. This paper addresses The Walt Disney Company's responses to two attacks on US soil: the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941 and the attacks on September 11, 200l and examines the similarities and differences between the two. By utilizing interviews from Disney employees, animated film shorts, historical accounts, insignia, government documents, and newspaper articles, this paper analyzes the continuity of Disney's methods of dealing with tragedy by controlling the narrative through Disneyfication, employing patriotic rhetoric, and reiterat- ing the original values that form Disney's utopian image. Disney's respon- siveness to changing social and political climates and use of varying mediums in its reactions to harsh realities contributes to the company's enduring rep- utation and presence in American culture. 1 Introduction A young Walt Disney craftily grabbed some shoe polish and cardboard, donned his father's coat, applied black crepe hair to his chin, and went about his day to his fifth-grade class. -

I. Regionale Organisation Des SD

I. Regionale Organisation des SD 1. Räumliche Gliederung Analog zu seiner Stellung im Gefüge der nationalsozialistischen Herrschaft war auch die räumliche Gliederung des Sicherheitsdienstes nicht statisch, sondern stän- dig im Wandel begriffen. Die äußere Hülle präsentiert sich unstetig und ist ähnlich schwer zu fassen wie sein innerer Charakter. Zwischen 1932 und 1945 wurden fast im Jahresrhythmus Reorganisationen durchgeführt, die die räumlichen Grenzzie- hungen und regionalen Unterstellungsverhältnisse immer wieder veränderten.1 Dies trifft besonders auf den mitteldeutschen Raum zu, der mit den Ländern Sachsen, Thüringen, Anhalt und Preußen bereits auf staatlicher Seite stark zer- klüftet war.2 Deshalb scheint hier eine Darstellung, die - anders als der größte Teil dieser Arbeit - dem Ablauf auf der Zeitachse chronologisch folgen wird, ange- bracht, um weiterführende Prozesse und Merkmale in ihrer regionalen Reichweite richtig abschätzen zu können. Im Hinblick auf den regionalen Schwerpunkt dieser Arbeit wird die besondere Aufmerksamkeit auf der Entwicklung im Land Sachsen liegen. Um für dieses Land die Verbindung von der Organisationsgeschichte zur Bio- grafieforschung zu finden, werden in einem direkt anschließenden Exkurs die ent- scheidenden SD-Führer porträtiert. Da es sowohl aus den zentralistischen Organi- sationsstrukturen heraus als auch von der Selbsteinschätzung dieser Männer her nie einen spezifisch „sächsischen" Sicherheitsdienst gegeben hat, ist Mitteldeutsch- land die entscheidende Größe. Im biografischen Teil soll es darum gehen, welchen biografischen Hintergrund die Männer hatten, die die Strukturen ausfüllten. Um diese regionale Elite einord- nen, ihre spezifische Mentalität und die von Heydrich zugewiesene Aufgabe als an allen Fronten einsetzbare politische Kämpfer erkennen zu können, darf sich die Darstellung nicht auf deren Zeit in Sachsen beschränken. -

Racial Ideology Between Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany: Julius Evola and the Aryan Myth, 1933–43

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications History, Department of 7-1-2020 Racial Ideology between Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany: Julius Evola and the Aryan Myth, 1933–43 Peter Staudenmaier Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/hist_fac Part of the History Commons Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications/College of Arts and Sciences This paper is NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION. Access the published version via the link in the citation below. Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 55, No. 3 (July 1, 2020): 473-491. DOI. This article is © SAGE Publications and permission has been granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. SAGE Publications does not grant permission for this article to be further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without express permission from SAGE Publications. Racial Ideology between Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany: Julius Evola and the Aryan Myth, 1933–43 Peter Staudenmaier Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI Abstract One of the troublesome factors in the Rome–Berlin Axis before and during the Second World War centered on disagreements over racial ideology and corresponding antisemitic policies. A common image sees Fascist Italy as a reluctant partner on racial matters, largely dominated by its more powerful Nazi ally. This article offers a contrasting assessment, tracing the efforts by Italian theorist Julius Evola to cultivate a closer rapport between Italian and German variants of racism as part of a campaign by committed antisemites to strengthen the bonds uniting the fascist and Nazi cause. Evola's spiritual form of racism, based on a distinctive interpretation of the Aryan myth, generated considerable controversy among fascist and Nazi officials alike.