Romanian Philosophical Studies, VI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Between Worlds Contents

BETWEEN WORLDS CONTENTS 14 Acknowledgments 16 Introduction Timothy 0. Benson and Eva Forgacs SECTION 1: STYLE AS THE CRUCIBLE OF PAST AND FUTURE Chapter 1: National Traditions Germany Carl Vinnen. "Quousque Tandem," from A Protest of German Artists [1911I Wilhelm Worringer, "The Historical Development of Modern Art," from The Struggle for Art (1911) Czech-Speaking Lands Milos Jiranek, "The Czechness of our Art," Radikatni iisty (1900I Bohumil Kubista, "Josef Manes Exhibition at the Topic Salon," Prehled ii9ii) Poland Juliusz Kaden-Bandrowski, "Wyspiariski as a Painter-Poet (Personal Impressions]," Przeglqd Poranny I1907] Stanistaw Witkiewicz, Excerpts from Jon Matejko (1908) Jacek Malczewski, "On the Artist's Calling and the Tasks of Art" I1912I Wtodzirnierz Zu-tawski, "Wyspiariski's Stained Glass Windows at the Wawel Cathedral," Maski (1918] Hungary Lajos Fulep, Excerpt from Hungarian Art I1916I Yugoslavia Exhibition Committee of University Youth (Belgrade], Invitation Letter (1904) Chapter 2: New Alternatives Prague Emil Filla, "Honore Daumier: A Few Notes on His Work," Volne smery (1910] Pavel Janak, "The Prism and the Pyramid" Umeiecky mesicnik (1911] Otto Gutfreund, "Surface and Space," Umeiecky mesicnik (1912) Emil Filla, "On the Virtue of Neo-Primitivism," Volne smery (1912) Vaclav Vilem Stech, Introduction to the second Skupina exhibition catalogue (1912) Bohumil Kubista, "The Intellectual Basis of Modern Time," Ceska kutturo I1912-13] Josef Capek, Fragments of correspondence I1913] Josef Capek, "The Beauty of Modern Visual Form," Printed [1913-14I Vlastislav Hofman, "The Spirit of Change in Visual Art," Almanoch no rok [1914) Budapest Gyb'rgy Lukacs, "Forms and the Soul," Excerpt from Richard Beer-Hoffmann 11910) Karoly Kernstok, "Investigative Art," Nyugat (1910) Gyorgy Lukacs, "The Ways Have Parted," Nyugat [1910) Karoly Kernstok, The Role of the Artist in Society," Huszadik szazad (1912) Bucharest Ion Minulescu, Fragment from "Light the Torches," Revisto celorlaiti (1908) N. -

OER STURM Oo PQ Os <Rh IRH ZEMIT A

De Styl 2x2 <rH IRH & Weimar Biflxelles OER STURM L'ESPRIT Berlin £ Wlan NOUVEAU 3 o CO a LA o .6 VIE o s £ D E Paris PQ S IU LETTRES DIE AKTION ET DES ARTS Paris ZEMIT Berlin Berlin InternaclonAIlt akllvlsta mQv^ssetl foly61rat • Sserkeutl: KattAk Uijof m Fe- leldssievkesxtO: Josef Kalmer • Sxerkesxtds^g £• klad6hlvafal: Wlen, XIIL Bei* Amallenstrasse 26. L 11 • Megjelen^s dAtuma 1922 oktdber 19 m EUfflrctM Ar: EOT £VRE: 3S.OOO osztr&k kor^ 70 ssokol, lOO dlnAr, 200 lei, SOO mArka m EQTE8 SZXM XltA: 3000 ositrAk korona, 7 siokol, lO dlnAr, 20 lei, SO mArka MA •b VIE 6vfolyam, 1. tx6m • A lapban megJelenO clkkek6rt a weriO felel. Drackerei .Elbemflfcl", Wien, IX., Berggtue 31. a sourcebook of central european avant-gardes, 1910-1930 CONTENTS 14 Acknowledgments 16 | Introduction Timothy 0. Benson and Eva Forgacs 49 Germany 50 Carl Vinnen, "Quousque Tandem," from A Protest of German Artists (1911) 52 Wilhelm Worringer, "The Historical Development of Modern Art," from The Struggle for Art (1911) 55 Czech-Speaking Lands 56 Milos Jiranek, "The Czechness of our Art," Radikalni tisty (1900) 57 Bohumil Kubista, "Josef Manes Exhibition at the Topic Salon," Prehled [1911) 59 Poland 60 ; Juliusz Kaden-Bandrowski, "Wyspianski as a Painter-Poet (Personal Impressions)," Przeglad Poranny (1907) 61 Stanistaw Witkiewicz, Excerpts from Jan Matejko (1908) 64 Jacek Malczewski, "On the Artist's Calling and the Tasks of Art" (1912) 66 Wiodzimierz Zutawski, "Wyspianski's Stained Glass Windows at the Wawel Cathedral," Maski (1918) 70 Hungary 71 ! Lajos Fulep, -

Romania's Cultural Wars: Intellectual Debates About the Recent Past

ROMANIA'S CULTURAL WARS : Intellectual Debates about the Recent Past Irina Livezeanu University of Pittsburgh The National Council for Eurasian and East European Researc h 910 17`" Street, N.W . Suite 300 Washington, D.C. 2000 6 TITLE VIII PROGRAM Project Information* Contractor : University of Pittsburgh Principal Investigator: Irina Livezeanu Council Contract Number : 816-08 Date : March 27, 2003 Copyright Informatio n Individual researchers retain the copyright on their work products derived from research funde d through a contract or grant from the National Council for Eurasian and East European Researc h (NCEEER). However, the NCEEER and the United States Government have the right to duplicat e and disseminate, in written and electronic form, reports submitted to NCEEER to fulfill Contract o r Grant Agreements either (a) for NCEEER's own internal use, or (b) for use by the United States Government, and as follows : (1) for further dissemination to domestic, international, and foreign governments, entities and/or individuals to serve official United States Government purposes or (2) for dissemination in accordance with the Freedom of Information Act or other law or policy of th e United States Government granting the public access to documents held by the United State s Government. Neither NCEEER nor the United States Government nor any recipient of this Report may use it for commercial sale . * The work leading to this report was supported in part by contract or grant funds provided by th e National Council for Eurasian and East European Research, funds which were made available b y the U.S. Department of State under Title VIII (The Soviet-East European Research and Trainin g Act of 1983, as amended) . -

Curriculum Vitae

JOSEPH ACQUISTO Professor of French Chair, Department of Romance Languages and Linguistics University of Vermont 517 Waterman Building Burlington, VT 05405 [email protected] (802) 656-4845 EDUCATION Yale University Ph.D., Department of French (2003) M.Phil., French (2000) M.A., French (1998) University of Dayton B.A., summa cum laude, French (1997) B.Mus., summa cum laude, voice performance (1997) EMPLOYMENT HISTORY Chair, Department of Romance Languages and Linguistics, University of Vermont 2016-present Professor of French, University of Vermont 2014-present Associate Professor of French with tenure, University of Vermont 2009-2014 Assistant Professor of French, University of Vermont 2003-2009 BOOKS 7. Poetry’s Knowing Ignorance, under consideration 6. Proust, Music, and Meaning: Theories and Practices of Listening in the Recherche, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017. 5. The Fall Out of Redemption: Writing and Thinking Beyond Salvation in Baudelaire, Cioran, Fondane, Agamben, and Nancy. New York: Bloomsbury, 2015. Paperback edition 2016. 4. Poets as Readers in Nineteenth-Century France: Critical Reflections, co-edited volume with Adrianna M. Paliyenko and Catherine Witt. London: Institute of Modern Languages Research, 2015. 3. Thinking Poetry: Philosophical Approaches to Nineteenth-Century French Poetry, edited volume. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. 1 2. Crusoes and Other Castaways in Modern French Literature: Solitary Adventures. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2012. Paperback edition 2014. 1. French Symbolist Poetry and the Idea of Music. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006. EDITED SPECIAL ISSUE The Cultural Currency of Nineteenth-Century French Poetry, a special double issue of Romance Studies (26:3-4, July/November 2008) co-edited and prefaced with Adrianna M. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Language and Theology in St Gregory of Nyssa

Durham E-Theses Language and theology in St Gregory of Nyssa Neamµu, Mihail G. How to cite: Neamµu, Mihail G. (2002) Language and theology in St Gregory of Nyssa, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4187/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk University of Durham Faculty of Arts Department of Theology The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Language and Theology in St Gregory of Nyssa Mihail G. Neamtu St John's College September 2002 M.A. in Theological Research Supervisor: Prof Andrew Louth This dissertation is the product of my own work, and the work of others has been properly acknowledged throughout. Mihail Neamtu Language and Theology in St Gregory of Nyssa MA (Research) Thesis, September 2002 Abstract This MA thesis focuses on the work of one of the most influential and authoritative theologians of the early Church: St Gregory of Nyssa (f396). -

Download Programme PDF Format

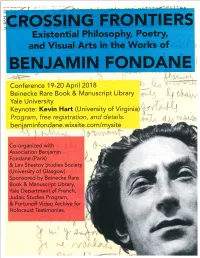

CROSSING FRONTIERS EXISTENTIAL PHILOSOPHY, POETRY, AND VISUAL ARTS IN THE WORKS OF BENJAMIN FONDANE BEINECKE RARE BOOK AND MANUSCRIPT LIBRARY YALE UNIVERSITY APRIL 19-20, 2018 Keynote Speaker: Prof. Kevin Hart, Edwin B. Kyle Professor of Christian Studies, University of Virginia Organizing Committee: Michel Carassou, Thomas Connolly, Julia Elsky, Ramona Fotiade, Olivier Salazar-Ferrer Administration: Ann Manov, Graduate Student & Webmaster Agnes Bolton, Administrative Coordinator “Crossing Frontiers” has been made possible by generous donations from the following donors: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies, Yale University Judaic Studies Program, Yale University Department of French, Yale University The conference has been organized in conjunction with the Association Benjamin Fondane (Paris) and the Lev Shestov Studies Society (University of Glasgow) https://benjaminfondane.wixsite.com/mysite THURSDAY, APRIL 19 Coffee 10.30-11:00 Panel 1: Philosophy and Poetry I 11.00-12.30 Room B 38-39 Chair: Alice Kaplan (Yale University) Bruce Baugh (Thompson Rivers University), “Benjamin Fondane: From Poetry to a Philosophy of Becoming” Olivier Salazar-Ferrer (University of Glasgow), “Revolt and Finitude in the Representation of Odyssey” Michel Carassou (Association Benjamin Fondane), “De Charlot à Isaac Laquedem. Figures de l’émigrant dans l’œuvre de Benjamin Fondane” [in French] Lunch in New Haven 12.30-14.30 Panel 2: Philosophy and Poetry II 14.30-16.00 Room B 38-39 Chair: Maurice Samuels (Yale University) Alexander Dickow (Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University), “Rhetorical Impurity in Benjamin Fondane’s Poetic and Philosophical Works” Cosana Eram (University of the Pacific), “Consciousness in the Abyss: Benjamin Fondane and the Modern World” Chantal Ringuet (Brandeis University), “A World Upside Down: Marc Chagall’s Yiddish Paradise According to Benjamin Fondane” Keynote 16.15 Prof. -

A New Decade for Social Changes

Vol. 21, 2021 A new decade for social changes ISSN 2668-7798 www.techniumscience.com 9 772668 779000 Technium Social Sciences Journal Vol. 21, 846-852, July, 2021 ISSN: 2668-7798 www.techniumscience.com The concept of transcendence in philosophy and theology Petrov George Daniel Theology Faculty, Ovidius University – Constanța, România [email protected] Abstract. The transcendence of God is the most sensitive and profound subject that could be addressed by the most enlightened minds of the world. In sketching this concept, the world of philosophy and that of theology are trying the impossible: to define the Absolute. Each approach is different, the first being subjected to reason, reaching specific conclusions, and the second, by understanding God's Personal character, appealing to the experience of living your life in God. The debate between the two worlds, that of philosophy and that of theology can only bring a plus to knowledge, while impressing any wisdom lover. Keywords. God, transcendence, immanence, Plato, Cioran, Heidegger, Hegel, Stăniloae I. Introduction The concept of transcendence expresses its importance through its ability to attract the intellect into deep research, out of a desire to express the inexpressible. The God of Theology was often named and defined by the world of philosophy in finite words, that could not encompass the greatness of the inexpressible. They could, however, rationally describe the Divinity, based on the similarities between the divine attributes and those of the world. Thus, in the world of great thinkers, God bears different names such as The Prime Engine, out of a desire to highlight the moment zero of time, Absolute Identity and even Substance, to express the immateriality of the Cause of all causes. -

TITUS LATES, N. Bagdasar. O Reevaluare

FILOSOFIE ROMÂNEASCĂ NICOLAE BAGDASAR. O REEVALUARE BIBLIOGRAFICĂ TITUS LATES Institutul de Filosofie şi Psihologie „Constantin Rădulescu-Motru” al Academiei Române Nicolae Bagdasar. Bibliography. The following pages represent a comprehensive bibliography of the romanian philosopher N. Bagdasar’s work, author of a monumental book on the Theory of knowledge (Teoria cunoştinţei), as well as a remarkable historian of philosophy. Among the many activities in the field of philosophy he was the editorial secretary for „Revista de filosofie”, between 1928–1943, where he published many studies, articles and reviews. Keywords: N. Bagdasar, Romanian philosophy, history of philosophy, „Revista de filosofie”, bibliography. Odată cu publicarea, în cursul anului 2014, în şase numere consecutive ale „Revistei de filosofie”, a unei ample selecţii din lucrarea în manuscris a lui Nicolae Bagdasar, Autori şi opere existenţialiste, se conturează posibilitatea unei noi abordări a operei filosofului român, în întregul ei. Propun pentru început o reevaluare bibliografică, cu atât mai necesară cu cât toate bibliografiile de până acum, care i-au fost dedicate, sunt fie sumare sau incomplete, fie trunchiate ori fără trimiteri bibliografice exacte. Am încercat să îndepărtez, măcar în parte, aceste neajunsuri şi am completat bibliografia cu apariţii din ultimii ani, menţionând o serie de reeditări şi antologări de texte. Apariţia acestei bibliografii în paginile „Revistei de filosofie” este cât se poate de potrivită, deoarece Nicolae Bagdasar şi-a desfăşurat aici o bună parte din activitate, între anii 1928–1943, publicând numeroase studii, articole şi recenzii. În calitate de secretar de redacţie, probabil tot el a redactat multe dintre paginile revistei care nu au fost semnate şi nu sunt semnalate mai jos. -

ROMANIAN IDENTITY and CULTURAL POLITICS UNDER CEAU§ESCU: an EXAMPLE from PHILOSOPHY1 Katherine Verdery

ROMANIAN IDENTITY AND CULTURAL POLITICS UNDER CEAU§ESCU: AN EXAMPLE FROM PHILOSOPHY1 Katherine Verdery Studies of intellectuals, their relation to power, and their role in shaping social ideologies' occupy an important place in twentieth-century social science (e.g., Mannheim 1955, Gramsci 1971, Shils 1958, Gouldner 1979, Foucault 1978 and 1980, Bourdieu 1975 and 1988, Konri.\d and Szelenyi 1979, Bauman 1987). While earlier writings (such as Shils 1958 and Coser 1965) treatec;i intellectual activity as "free-floating" and as relatively independent of political interest, the consensus of the 1970s and 1980s emphasizes, rather, that intellectual production is situated, embedded in political and social relations. Different theorists have different views concerning the political character of scientific findings and scholarly debates. Some emphasize the ways in which knowledge develops practices that contribute to subjection (e.g., Bauman 1987, Foucault 1978); others focus on the politics that occur within afield of intellectual activity and on how that field is tied to political and eco~omic processes in. the society as a whole (e.g., .Abbott 1988, Bourdieu 1975, 1988). Still others examine how the discourses of "intellectuals build up ideological premises that either construct or challenge social hegemonies (e.g., Simmonds-Duke 1987). This essay, and the study of which it forms a part (Verdery 1991), follow the third of these routes. My objective is to investigate how intellectual activity in Romania under ceau~escu contributed to reproducing -

Emil Cioran – a Deconstructive Philosophy

EMIL CIORAN – A DECONSTRUCTIVE PHILOSOPHY Angela Botez∗∗∗ [email protected] Abstract: For Cioran, expressing (something, someone) is the same with a postponed ripost or an aggression left for lateron and his writing is a solution, not to act, to avoid a crisis. His indignation is not as much a moral outset, as it is a literary one, the resort of inspiration, while wisdom wearies us of any momentum. The writer is a lunatic who uses in curative purposes these fictions we call words. For the Romanian philosopher the most uncomfortable relation is precisely with philosophy explaining that meeting the idea face to face incites us to talk nonsense, and clouds our judgement and produces the illusion of almightiness... All our deregulations and aberrations are triggered by the fight we lead with the irrealities, with the abstractions, with our will to conquer what does not exist, and from hereon also the impure, tiranical and delirious aspect of the philosophical works... Keywords: Emil Cioran, deconstructivism, antifoundationalism, philosophy of life, despair, and end of philosophy. Among the Romanian philosophers, the most explicit postmodern position of a deconstructive nihilistic type was Emil Cioran. In his work Exercises d’admiration: essais et portraits,1 published in the Romanian version by the Humanitas Publishing House in 1993, there is an article entitled Relecturing, resulted, according to the confession of the author, from the intention to present to the German readers his Précis de décomposition translated from French to German by Paul Celan, in 1953, and edited in 1978. The text gives a glimpse of the type of philosophy promoted by Emil Cioran, inscribed, obviously, among the postmodernist, antifoundationalist, nihilist, and deconstructivist tendencies. -

Hypothesis on Tararira, Benjamin Fondane's Lost Film

www.unatc.ro Academic Journal of National University of Theatre and Film “I.L. Caragiale” – Vol. 2, No. 1, 2018 UNATC PRESS UNATC The academic journal of the National University of Theatre and Film “I.L. Caragiale“ publishes original papers aimed to analyzing in-depth different aspects of cinema, film, television and new media, written in English. You can find information about the way to submit papers on cover no 3 and at the Internet address: www.unatc.ro Editor in chief: Dana Duma Deputy editor: Andrei Gorzo [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Managing Editor: Anca Ioniţă [email protected] Copy Editor: Andrei Gorzo, Anca Ioniță Editorial Board: Laurenţiu Damian, Dana Duma, Andrei Gorzo, Ovidiu Georgescu, Marius Nedelcu, Radu Nicoară Advisory Board: Dominique Nasta (Université Libre de Bruxelles) Christina Stojanova (Regina University, Canada) Tereza Barta (York University, Toronto, Canada) UNATC PRESS ISSN: 2343 – 7286 ISSN-L: 2286 – 4466 Art Director: Alexandru Oriean Photo cover: Vlad Ivanov in Dogs by Bogdan Mirică Printing House: Net Print This issue is published with the support of The Romanian Filmmakers’ Union (UCIN) National University of Theatre and Film “I.L. Caragiale” Close Up: Film and Media Studies Vol. 2, No. 1, 2018 UNATC PRESS BUCUREȘTI CONTENTS Close Up: Film and Media Studies • Vol. 2, No. 1, 2018 Christina Stojanova Some Notes on the Phenomenology of Evil in New Romanian Cinema 7 Dana Duma Hypothesis on Tararira, Benjamin Fondane’s Lost Film 19 Andrei Gorzo Making Sense of the New Romanian Cinema: Three Perspectives 27 Ana Agopian For a New Novel.