An Actress's Journey Through Pointillism to Define the Role of Dot in Sondheim and Lapine's Musical Sunday in the Park with George

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heather Buckner Vitaglione Mlitt Thesis

P. SIGNAC'S “D'EUGÈNE DELACROIX AU NÉO-IMPRESSIONISME” : A TRANSLATION AND COMMENTARY Heather Buckner Vitaglione A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of MLitt at the University of St Andrews 1985 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/13241 This item is protected by original copyright P.Signac's "D'Bugtne Delacroix au n6o-impressionnisme ": a translation and commentary. M.Litt Dissertation University or St Andrews Department or Art History 1985 Heather Buckner Vitaglione I, Heather Buckner Vitaglione, hereby declare that this dissertation has been composed solely by myself and that it has not been accepted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a candidate for the degree of M.Litt. as of October 1983. Access to this dissertation in the University Library shall be governed by a~y regulations approved by that body. It t certify that the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations have been fulfilled. TABLE---.---- OF CONTENTS._-- PREFACE. • • i GLOSSARY • • 1 COLOUR CHART. • • 3 INTRODUCTION • • • • 5 Footnotes to Introduction • • 57 TRANSLATION of Paul Signac's D'Eug~ne Delac roix au n~o-impressionnisme • T1 Chapter 1 DOCUMENTS • • • • • T4 Chapter 2 THE INFLUBNCB OF----- DELACROIX • • • • • T26 Chapter 3 CONTRIBUTION OF THE IMPRESSIONISTS • T45 Chapter 4 CONTRIBUTION OF THB NEO-IMPRBSSIONISTS • T55 Chapter 5 THB DIVIDED TOUCH • • T68 Chapter 6 SUMMARY OF THE THRBE CONTRIBUTIONS • T80 Chapter 7 EVIDENCE • . • • • • • T82 Chapter 8 THE EDUCATION OF THB BYE • • • • • 'I94 FOOTNOTES TO TRANSLATION • • • • T108 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • • T151 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Plate 1. -

JULIETA by Pedro Almodóvar

JULIETA by Pedro Almodóvar Julieta’s three houses in Madrid, at the three different stages in the story: House 1 is the one she shares with her daughter Antía, after Xoan’s death. 19, Fernando VI, Third Floor. From 1998 to 2006-2007. House 2 is the one to which she moves, after throwing out all the reminders of her daughter. A neutral, ugly neighborhood far from the center. Shortly after, Ava dies and Lorenzo appears in her life. 2006-2007 to 2016. House 3 is in the same building as House 1, 19, Fernando VI, Second Floor. Julieta moves there immediately after her encounter with Beatriz. At that moment she decides to stay in Madrid and not go to Portugal with Lorenzo. From 2016 to the end. 1. MADRID. JULIETA’S HOUSE 2. INT. IN THE MORNING. 2016. SPRING A red fabric fills the screen. Over it appear the opening credits. At first it gives a sensation of stillness, but with the insistence of the shot we discover that the fabric is moving, a slight, rhythmic movement. We discover that the fabric is the front of a dress and that Julieta’s heart is beating inside it. Julieta, an attractive woman of 55, independent and full of determination, a mixture of timidity and daring, fragility and courage. Blond. She is sitting next to a bookcase, surrounded by cardboard boxes, the kind used for moving house. She picks up a sculpture of naked, seated man, with the color and texture of terracotta (some 8 inches high), and wraps it carefully in bubble wrap. -

André Derain Stoppenbach & Delestre

ANDR É DERAIN ANDRÉ DERAIN STOPPENBACH & DELESTRE 17 Ryder Street St James’s London SW1Y 6PY www.artfrancais.com t. 020 7930 9304 email. [email protected] ANDRÉ DERAIN 1880 – 1954 FROM FAUVISM TO CLASSICISM January 24 – February 21, 2020 WHEN THE FAUVES... SOME MEMORIES BY ANDRÉ DERAIN At the end of July 1895, carrying a drawing prize and the first prize for natural science, I left Chaptal College with no regrets, leaving behind the reputation of a bad student, lazy and disorderly. Having been a brilliant pupil of the Fathers of the Holy Cross, I had never got used to lay education. The teachers, the caretakers, the students all left me with memories which remained more bitter than the worst moments of my military service. The son of Villiers de l’Isle-Adam was in my class. His mother, a very modest and retiring lady in black, waited for him at the end of the day. I had another friend in that sinister place, Linaret. We were the favourites of M. Milhaud, the drawing master, who considered each of us as good as the other. We used to mark our classmates’s drawings and stayed behind a few minutes in the drawing class to put away the casts and the easels. This brought us together in a stronger friendship than students normally enjoy at that sort of school. I left Chaptal and went into an establishment which, by hasty and rarely effective methods, prepared students for the great technical colleges. It was an odd class there, a lot of colonials and architects. -

Daxer & Marschall 2015 XXII

Daxer & Marschall 2015 & Daxer Barer Strasse 44 - D-80799 Munich - Germany Tel. +49 89 28 06 40 - Fax +49 89 28 17 57 - Mobile +49 172 890 86 40 [email protected] - www.daxermarschall.com XXII _Daxer_2015_softcover.indd 1-5 11/02/15 09:08 Paintings and Oil Sketches _Daxer_2015_bw.indd 1 10/02/15 14:04 2 _Daxer_2015_bw.indd 2 10/02/15 14:04 Paintings and Oil Sketches, 1600 - 1920 Recent Acquisitions Catalogue XXII, 2015 Barer Strasse 44 I 80799 Munich I Germany Tel. +49 89 28 06 40 I Fax +49 89 28 17 57 I Mob. +49 172 890 86 40 [email protected] I www.daxermarschall.com _Daxer_2015_bw.indd 3 10/02/15 14:04 _Daxer_2015_bw.indd 4 10/02/15 14:04 This catalogue, Paintings and Oil Sketches, Unser diesjähriger Katalog Paintings and Oil Sketches erreicht Sie appears in good time for TEFAF, ‘The pünktlich zur TEFAF, The European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht, European Fine Art Fair’ in Maastricht. TEFAF 12. - 22. März 2015, dem Kunstmarktereignis des Jahres. is the international art-market high point of the year. It runs from 12-22 March 2015. Das diesjährige Angebot ist breit gefächert, mit Werken aus dem 17. bis in das frühe 20. Jahrhundert. Der Katalog führt Ihnen The selection of artworks described in this einen Teil unserer Aktivitäten, quasi in einem repräsentativen catalogue is wide-ranging. It showcases many Querschnitt, vor Augen. Wir freuen uns deshalb auf alle Kunst- different schools and periods, and spans a freunde, die neugierig auf mehr sind, und uns im Internet oder lengthy period from the seventeenth century noch besser in der Galerie besuchen – bequem gelegen zwischen to the early years of the twentieth century. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1k1860wx Author Ellis, Sarah Taylor Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies by Sarah Taylor Ellis 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater by Sarah Taylor Ellis Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Sue-Ellen Case, Co-chair Professor Raymond Knapp, Co-chair This dissertation explores queer processes of identification with the genre of musical theater. I examine how song and dance – sites of aesthetic difference within the musical – can warp time and enable marginalized and semi-marginalized fans to imagine different ways of being in the world. Musical numbers can complicate a linear, developmental plot by accelerating and decelerating time, foregrounding repetition and circularity, bringing the past to life and projecting into the future, and physicalizing dreams in a narratively open present. These excesses have the potential to contest naturalized constructions of historical, progressive time, as well as concordant constructions of gender, sexual, and racial identities. While the musical has historically been a rich source of identification for the stereotypical white gay male show queen, this project validates a broad and flexible range of non-normative readings. -

KEVIN COLE “America's Pianist” Kevin Cole Has Delighted

KEVIN COLE “America’s Pianist” Kevin Cole has delighted audiences with a repertoire that includes the best of American Music. Cole’s performances have prompted accolades from some of the foremost critics in America. "A piano genius...he reveals an understanding of harmony, rhythmic complexity and pure show-biz virtuosity that would have had Vladimir Horowitz smiling with envy," wrote critic Andrew Patner. On Cole’s affinity for Gershwin: “When Cole sits down at the piano, you would swear Gershwin himself was at work… Cole stands as the best Gershwin pianist in America today,” Howard Reich, arts critic for the Chicago Tribune. Engagements for Cole include: sold-out performances with the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl; BBC Concert Orchestra at Royal Albert Hall; National Symphony at the Kennedy Center; Hong Kong Philharmonic; San Francisco Symphony, Chicago Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, Philharmonia Orchestra (London); Boston Philharmonic, Adelaide Symphony Orchestra (Australia) Minnesota Orchestra, Pittsburgh Symphony, Dallas Symphony, Seattle Symphony,Vietnam National Symphony Orchestra; New Zealand Symphony, Edmonton Symphony (Canada), Ravinia Festival, Wolf Trap, Savannah Music Festival, Castleton Festival, Chautauqua Institute and many others. He made his Carnegie Hall debut with the Albany Symphony in May 2013. He has shared the concert stage with, William Warfield, Sylvia McNair, Lorin Maazel, Brian d’Arcy James, Barbara Cook, Robert Klein, Lucie Arnaz, Maria Friedman, Idina Menzel and friend and mentor Marvin Hamlisch. Kevin was featured soloist for the PBS special, Gershwin at One Symphony Place with the Nashville Symphony. He has written, directed, co- produced and performed multimedia concerts for: The Gershwin’s HERE TO STAY -The Gershwin Experience, PLAY IT AGAIN, MARVIN!-A Celebration of the music of Marvin Hamlisch with Pittsburgh Symphony and Chicago Symphony and YOU’RE THE TOP!-Cole Porter’s 125th Birthday Celebration and I LOVE TO RHYME – An Ira Gershwin Tribute for the Ravinia Festival with Chicago Symphony. -

Fauvism (Henri Matisse) Non-Realistic Colours Are Used but the Paintings Are Seemingly Realistic

Non-Photorealistic Rendering of Images Work Division This project has been dealt with in three phases- Phase 1 Identifying explicit features Phase 2 Verification using viewers Phase 3 Technology(Coding) Phase 1 In this phase we tried to identify the explicit features in a group of paintings belonging to the same period and/or to the same artist. Following are the styles we implemented using image processing tools Fauvism Pointillism Cubism Divisionism Post Impressionism(Van Gogh) Phase 1 Fauvism The subject matter is simple. The paintings are made up of non-realistic and strident colours and are characterized by wild brush work. Phase 1 Pointillism We noticed that the paintings had a lot of noise in them and it looked like they were made by grouping many dots together in a proper way. There’s no focus on the separation of colours. Phase 1 Cubism It looked as if the painting was looked through a shattered glass which makes it look distorted. Phase 1 Divisionism The paintings are made up of small rectangles with curved edges each with a single colour which interact visually. Phase 1 Post Impressionism (Van Gogh) These paintings have small, thin yet visible brush strokes. They have a bright, bold palette. Unnatural and arbitrary colours are used. Phase 2 In this phase we verified the features we identified in phase 1 with other people We showed them a group of paintings belonging to a certain era and/or an artist and asked them to write down the most striking features common to all those paintings. Phase 2 Here are the inferences we made from the statistics collected Fauvism (Henri Matisse) Non-realistic colours are used but the paintings are seemingly realistic. -

An Interdisciplinary Journal of Undergraduate Research

Knighted An Interdisciplinary Journal of Undergraduate Research 2021 Issue 4 Table of Contents Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………………….1 Introduction Welcome, Editorial Board, Mission, Submission Guidelines…………………………….2 Shakespeare’s Socioeconomics of Sack: Elizabethan vs. Jacobean as depicted by Falstaff in Henry IV, Part I, Christopher Sly in The Taming of the Shrew, and Stephano in The Tempest…………………………………………………………………………….Sierra Stark Stevens…4 The Devil Inside……...……………………………………………………...Sarah Istambouli...18 Blade Runner: The Film that Keeps on Giving…………………………..………Reid Vinson...34 Hiroshima and Nagasaki: A Necessary Evil….……………………..…………….Peter Chon…42 When Sharing Isn’t Caring: The Spread of Misinformation Post-Retweet/Share Button ……………………………………………………………...…………………Johnathan Allen…52 Invisible Terror: How Continuity Editing Techniques Create Suspense in The Silence of the Lambs…………………………………………………………………………..……..Garrentt Duffey…68 The Morality of Science in “Rappaccini’s Daughter” and Nineteenth- CenturyAmerica…………………………………………………………………Eunice Chon…76 Frederick Douglass: The Past, Present, and Future…………………………...Brenley Gunter…86 Identity and Color Motifs in Moonlight………………………………..................Anjunita Davis…97 Queerness as a Rebel’s Cause……………….………………………….Sierra Stark Stevens…108 The Deadly Cost of Justification: How the Irish Catholic Interpretation of the British Response to “Bloody Sunday” Elicited Outrage and Violence, January–April 1972……Garrentt Duffey…124 Steve Biko and the Black Consciousness Movement: How Young Students -

Programmi Svolti

Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca LICEO “P. NERVI – G. FERRARI” P.zza S. Antonio – 23017 Morbegno (So) Indirizzi: Artistico, Linguistico, Scientifico, Scientifico - opz. Scienze applicate, Scienze umane email certificata: [email protected] email Uffici: [email protected] – [email protected] Tel. 0342612541 - 0342610284 / Fax 0342600525 – 0342610284 C.F. 91016180142 https://www.nerviferrari.edu.it ANNO SCOLASTICO 2018/2019 ALLEGATO AL DOCUMENTO DEL CONSIGLIO DI CLASSE V AG LICEO ARTISTICO PROGRAMMI SVOLTI Morbegno, 3 giugno 2019 RELIGIONE ITALIANO INGLESE STORIA FILOSOFIA MATEMATICA FISICA LABORATORIO GRAFICA DISCIPLINE GRAFICHE_LABORATORIO GRAFICA STORIA DELL’ARTE SCIENZE MOTORIE E SPORTIVE ALLEGATO al Documento del Consiglio di classe – V AG Liceo Artistico – a.s. 2018/2019 1 PROGRAMMI SVOLTI LICEO “P. NERVI - G. FERRARI” - Morbegno (SO) MATERIA: RELIGIONE DOCENTE: don DIEGO FOGNINI PROGRAMMA SVOLTO - La responsabilità come impegna di persone autentiche e inserite nella vita quotidiana, non solo scolastica , ma anche sociale - L’etica applicata nelle relazioni, nel proprio lavoro scolastico e non e come deterrente all’illegalità - Fare dell’etica la propria professione - La solidarietà vista come impegno costante in tutte le fragilità sociali che ci circondano - La conoscenza di sé come forza per realizzare progetti di vita [torna all’elenco] ALLEGATO al Documento del Consiglio di classe – V AG Liceo Artistico – a.s. 2018/2019 2 PROGRAMMI SVOLTI LICEO “P. NERVI - G. FERRARI” - Morbegno (SO) MATERIA: ITALIANO DOCENTE: LUIGI NUZZOLI Libri di testo: Roncoroni, Dendi, Il rosso e il blu ed. blu vol. 3, Signorelli Dante, Paradiso, ed. a scelta PROGRAMMA SVOLTO Nota: i titoli delle letture antologiche si riferiscono a quelli del testo in adozione; alcuni testi sono stati forniti in fotocopia 1. -

Desperate Housewives a Lot Goes on in the Strange Neighborhood of Wisteria Lane

Desperate Housewives A lot goes on in the strange neighborhood of Wisteria Lane. Sneak into the lives of five women: Susan, a single mother; Lynette, a woman desperately trying to b alance family and career; Gabrielle, an exmodel who has everything but a good m arriage; Bree, a perfect housewife with an imperfect relationship and Edie Britt , a real estate agent with a rocking love life. These are the famous five of Des perate Housewives, a primetime TV show. Get an insight into these popular charac ters with these Desperate Housewives quotes. Susan Yeah, well, my heart wants to hurt you, but I'm able to control myself! How would you feel if I used your child support payments for plastic surgery? Every time we went out for pizza you could have said, "Hey, I once killed a man. " Okay, yes I am closer to your father than I have been in the past, the bitter ha tred has now settled to a respectful disgust. Lynette Please hear me out this is important. Today I have a chance to join the human rac e for a few hours there are actual adults waiting for me with margaritas. Loo k, I'm in a dress, I have makeup on. We didn't exactly forget. It's just usually when the hostess dies, the party is off. And I love you because you find ways to compliment me when you could just say, " I told you so." Gabrielle I want a sexy little convertible! And I want to buy one, right now! Why are all rich men such jerks? The way I see it is that good friends support each other after something bad has happened, great friends act as if nothing has happened. -

Državni Izpit ZAKLJUČNI DOKUMENT RAZREDNEGA SVETA 5

ISTITUTO STATALE DI ISTRUZIONE SUPERIORE CON LINGUA D'INSEGNAMENTO SLOVENA Liceo delle scienze umane e liceo scientifico "S. Gregorčič" Liceo classico „P. Trubar“ DRŽAVNI IZOBRAŽEVALNI ZAVOD S SLOVENSKIM UČNIM JEZIKOM Humanistični in znanstveni licej „S. Gregorčič“ Klasični licej „P. Trubar“ 34170 GORIZIA GORICA via/Ul. Puccini 14 tel. 0481 82123 – Pres./Ravn. 0481 32387 C.F./D.Š. 91021440317 email [email protected] Državni izpit Šolsko leto 2015/16 ZAKLJUČNI DOKUMENT RAZREDNEGA SVETA 5. RAZREDA ZNANSTVENEGA LICEJA OPCIJA UPORABNE ZNANOSTI Z DNE 15. MAJA 2016 odobren na seji razrednega profesorskega zbora dne 13. maja 2016 po 2. odst. 5. čl. OPR št. 323 z dne 23.7.1998 Zaključni dokument razrednega sveta 5. razreda znanstvene smeri (5.čl. pravilnika) 1. Predstavitev razreda a) Sestava razreda a) Razred sestavlja osem dijakov, pet iz Gorice in okoliških vasi, dva dijaka z Laskega in eden iz tržaške pokrajine. Razred je v prvem letniku stel 16 dijakov; 5 jih je zapustilo razred in zamenjalo smer po prvem letniku, ena dijakinja po drugem letniku, druga dijakinja pa se je v tretjem razredu vrnila v Slovenijo; tretja dijakinja je v cetrtem letniku izbrala studij v tujini. Seznam dijakov 1. Daneluzzo Jaroš 2. Furlan Jan 3. Giacomazzi Cecilia 4. Marvin Elena 5. Muller Philip 6. Pahor Katja 7. Papais Franceso 8. Zio Leonardo b) Po prvem letniku, ko je bilo v razredu zaznati kar nekaj tezav s strani vec dijakov, ki jih gre v glavnem pripisati novemu solskemu okolju in bolj zahtevnemu pristopu do solskega dela, je razred zapustilo sest dijakov. V naslednjih letih je v razredu zavladalo pozitivno in konstruktivno vzdušje tako, da je razred postal homogen kolektiv, v katerem je šolsko delo potekalo tekoce in brez vecjih ovir in zastojev. -

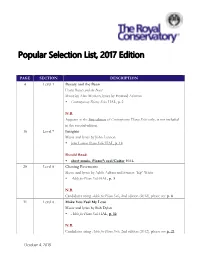

Popular Selection List, 2017 Edition

Popular Selection List, 2017 Edition PAGE SECTION DESCRIPTION 4 Level 1 Beauty and the Beast From Beauty and the Beast Music by Alan Menken; lyrics by Howard Ashman Contemporary Disney Solos HAL, p. 2 N.B. Appears in the first edition of Contemporary Disney Solos only, is not included in the second edition. 18 Level 7 Imagine Music and lyrics by John Lennon John Lennon Piano Solos HAL, p. 18 Should Read: sheet music, Piano/Vocal/Guitar HAL 20 Level 8 Chasing Pavements Music and lyrics by Adele Adkins and Francis “Eg” White Adele for Piano Solo HAL, p. 3 N.B. Candidates using Adele for Piano Solo, 2nd edition (2012), please see p. 8 21 Level 8 Make You Feel My Love Music and lyrics by Bob Dylan Adele for Piano Solo HAL, p. 12 N.B. Candidates using Adele for Piano Solo, 2nd edition (2012), please see p. 21 October 4, 2018 21 Level 8 Someone Like You Music and lyrics by Adele Adkins and Dan Wilson Adele for Piano Solo HAL, p. 30 N.B. Candidates using Adele for Piano Solo, 2nd edition (2012), please see p. 34 21 Level 8 Somewhere From West Side Story Music by Leonard Bernstein; lyrics by Stephen Sondheim West Side Story, Vocal Selections B&H, p. 64 Should Read: West Side Story, Vocal Selections B&H, p. 6 24 Level 9 One and Only Music and lyrics by Adele Adkins, Dan Wilson, and Greg Wells Adele for Solo Piano HAL, p. 15 N.B. Candidates using Adele for Piano Solo, 2nd edition (2012), please see p.