Degas: a New Vision and Seurat's Circus Sideshow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8 Places to Run Away with the Circus

chicagoparent.com http://www.chicagoparent.com/magazines/going-places/2016-spring/circus 8 places to run away with the circus The Actors Gymnasium Run away with the circus without leaving Chicago! If your child prefers to hang upside down while swinging from the monkey bars or tries to jump off a kitchen cabinet to reach the kitchen fan, he belongs in the circus. He’ll be able to squeeze out every last ounce of that energy, and it’s the one place where jumping, swinging, swirling and balancing on one foot is encouraged. Here are some fabulous places where your child can juggle, balance and hang upside down. MSA & Circus Arts 1934 N. Campbell Ave., Chicago; (773) 687-8840 Ages: 3 and up What it offers: Learn skills such as juggling, clowning, rolling globe, sports acrobatics, trampoline, stilts, unicycle 1/4 and stage presentation. The founder of the circus arts program, Nourbol Meirmanov, is a graduate of the Moscow State Circus school, and has recruited trained circus performers and teachers to work here. Price starts: $210 for an eight-week class. The Actors Gymnasium 927 Noyes St., Evanston; (847) 328-2795 Ages: 3 through adult (their oldest student at the moment is 76) What it offers: Kids can try everything from gymnastics-based circus classes to the real thing: stilt walking, juggling, trapeze, Spanish web, lyra, contortion and silk knot. Classes are taught by teachers who graduated from theater, musical theater and circus schools. They also offer programs for kids with disabilities and special needs. Price starts: $165 for an 8-10 week class. -

Circus Trailer *

* CIRCUS TRAILER * 4 GROUPS With the 4 circus techniques JUGGLING ---------- Gonzalo, François, Tjaz ---------- Target gropup: 6-9 years old, begginers Welcome: Magic Space General presentations: Whisper the facilitators names. a) Movements with one ball, the group repeats. b) Call somebody only with the movement made Specific Wam up: Desplacements throughout the space, dancing, with music and one ball each other a) block the ball b) write your name with the ball c) make differents throughts d) come back to the circle and present how you've written your name Exercise with juggling balls 2 groups. Chose a leader. a) The rest of the group, takes a marker all toghether, and with eyes closed, the Leader says to them the directions of the lines that they have to draw. b) transform the lines drawed in throughts and CatXing movements, giving them a number. c) put in order the number and create a groups choreograph d) present the choreography With scarfs: 3 each one a) Everyone with 3 scarfs, two on the hands and one on the floor. Standing up, through the scarf and take the one from the floor. 3 scarfs cascade. b)Try to move around the space once you can throw and catch. c) In a circle, through 1 sacrf and move to the right, catching the scarf of the one that is at your right. Diabolo/ and balls : Calm down: Each participant one diabolo in the head, with a ball inside the diabolo. Walk within letting down the diabolo, and change de ball inside with another. If the diablo falls, you frizz until somebody putts the diabolo/ball in your head. -

Woodstock & the Circus

LOCAL HISTORY WOODSTOCK & MCHENRY COUNTY Woodstock and the Circus by Kirk Dawdy Soon after its establishment in 1852 Woodstock became a consistent destination for circus shows. Several different outfits visited Woodstock over the years, including the Burr Robbins, Forepaugh, Cole, W.B. Reynolds, Gollmar Brothers, Ringling Brothers and Barnum circuses. The first documented circus in Woodstock was “Yankee” Robinson’s Quadruple Show in October of 1856. Robinson, a direct descendant of Pastor John Robinson, religious leader of the "Pilgrim Fathers" who journeyed to North America aboard the Mayflower, established his first travelling circus in 1854, two years prior to visiting Woodstock. An ardent abolitionist, Robinson included in his circuses minstrel shows based on Harriet Beecher Stowe's 1852 book Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In fact, Robinson was the very first to ever take a dramatized version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin on the road. In “Yankee” Robinson’s 1856 Woodstock visit, in addition to presenting a band of African-American minstrels performing in a production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, he also exhibited live animals (including an elephant), a museum of curiosities, Dilly Fay the Shanghai Clown and Miss Paintero, a ‘Creole Lady’ who made a grand ascension on a 400 foot tightrope to the very top of the circus tent. Also advertised for “Yankee’s” visit was a grand parade around the Woodstock square. Circus parades were a crowd favorite and staple for all other circuses that visited Woodstock, weather permitting. Feeling his name sounded too foreign, especially during the anti-immigrant sentiments of the mid-1850s, Fayette Lodawick Robinson adopted the professional name “Yankee”. -

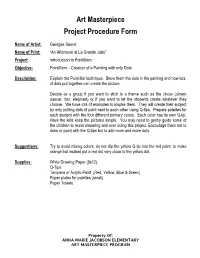

Art Masterpiece Project Procedure Form

Art Masterpiece Project Procedure Form Name of Artist: Georges Seurat Name of Print: “An Afternoon at La Grande Jatte” Project: Introduction to Pointillism Objective: Pointillism – Creation of a Painting with only Dots Description: Exlplain the Pointillist technique. Show them the dots in the painting and how lots of dots put together can create the picture. Decide as a group if you want to stick to a theme such as the circus (clowm dancer, lion, elephant) or if you want to let the students create whatever they choose. We have lots of examples to inspire them. They will create their subject by only putting dots of paint next to each other using Q-tips. Prepare palettes for each student with the four different primary colors. Each color has its own Q-tip. Have the kids keep the pictures simple. You may need to gently guide some of the children to resist smearing and over doing this project. Encourage them not to draw or paint with the Q-tips but to add more and more dots. Suggestions: Try to avoid mixing colors, do not dip the yellow Q-tip into the red paint, to make orange but instead put a red dot very close to the yellow dot. Supplies: White Drawing Paper (9x12) Q-Tips Tempera or Acrylic Paint (Red, Yellow, Blue & Green) Paper plates for palettes (small) Paper Towels Property Of: ANNA MARIE JACOBSON ELEMENTARY ART MASTERPIECE PROGRAM Georges Seurat (Zhorzh Soo-Rah) Seurat was born in 1859 in Paris. He was the son of a comfortably situated middle class family. -

How to Plan and Organize a Circus Workshop Page 2 Basics of Acrobalance Page 3

Index How to plan and organize a circus workshop page 2 Basics of acrobalance page 3 - Part 1 page 4 - Part 2 page 9 Basics of circus props page 15 - Juggling with balls page 17 - Chinese plate page 27 - Diabolo page 23 - Pois page 25 Balloon twisting workshop page 28 How to make your own props page 31 How to prepare a show page 33 Balance and equilibrism page 35 - Slack line page 36 - Stilts page 38 Anja in Denis Mikič Crovella: Circus pedagogy 2016, Cirkus La Bulle and Association CIK How to plan and organize a circus workshop There are several ways to build a program of circus workshops. The planning, organization and implementation of the workshop will depend on various factors. First of all: your pedagogical project . Consider the goals and aims of your organization. What is their main vision? Is it the personal development of the participants? Their physical development? In some cases you will organize workshop in collaboration with other organization. Also consider the goals and aims of your partners. Are they institutional partners? Etc. Then you have to think about yourself . What do you want to achieve by implementing a circus workshop? What are your pedagogical objectives? And how can you reach them? Do you aim to develop personal and social competences of your participant or do you want them only to have fun? Do you want to create a show with the participants? You will have to adapt your objectives to your capacities, that mean that you will have to think about your technical skills and your teaching skills (group management, organization…). -

Fedec Fédération Européenne Des Écoles De Cirque Professionnelles the Fedec 3

THE CIRCUS ARTIST TODAY ANALYSIS OF THE KEY COMPETENCES WHAT TYPE OF TRAINING IS NEEDED TODAY FOR WHAT TYPE OF ARTIST AND IN WHAT FIELD OF ACTIVITY? PASCAL JACOB FEDEC FÉDÉRATION EUROPÉENNE DES ÉCOLES DE CIRQUE PROFESSIONNELLES THE FEDEC 3 PREAMBLE 4 OBJECTIVES AND FINDINGS OF SURVEY 6 INTRODUCTION 7 The landscape – requirements and resources 7 Sources? 8 Methodological issues 9 FIRST PART 10 SOME REFERENCE POINTS 11 QUESTIONS OF PRINCIPLE 15 SECOND PART 18 TYPOLOGIES OF SETTINGS 19 QUESTIONNAIRE 25 - Inventory 25 - Objectives 26 - Analysis 26 - Expectations 27 THIRD PART 34 Transmission and validation 35 CONCLUSION 39 RECOMMENDATIONS 41 APPENDIX 45 Questionnaire used in survey 45 Students from the schools of the European Federation under contract in classic or contemporary circus businesses 47 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 49 This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication refl ects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. THE CIRCUS ARTIST TODAY ANALYSIS OF THE KEY COMPETENCES PERFORMANCE WITHOUT SPIRIT OR SPIRIT WITHOUT PERFORMANCE? WHAT TYPE OF TRAINING IS NEEDED TODAY FOR WHAT TYPE OF ARTIST AND IN WHAT FIELD OF ACTIVITY? PASCAL JACOB 1 2 THE FEDEC Created in 1998, the European Federation of Professional Circus Schools (FEDEC) is a network that is comprised of 38 professional circus schools located in 20 different countries (Albania, Australia, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Denmark, Finland, France, -

Pablo Picasso, One of the Most He Was Gradually Assimilated Into Their Dynamic and Influential Artists of Our Stimulating Intellectual Community

A Guide for Teachers National Gallery of Art,Washington PICASSO The Early Ye a r s 1892–1906 Teachers’ Guide This teachers’ guide investigates three National G a l l e ry of A rt paintings included in the exhibition P i c a s s o :The Early Ye a rs, 1 8 9 2 – 1 9 0 6.This guide is written for teachers of middle and high school stu- d e n t s . It includes background info r m a t i o n , d i s c u s s i o n questions and suggested activities.A dditional info r m a- tion is available on the National Gallery ’s web site at h t t p : / / w w w. n g a . gov. Prepared by the Department of Teacher & School Programs and produced by the D e p a rtment of Education Publ i c a t i o n s , Education Division, National Gallery of A rt . ©1997 Board of Tru s t e e s , National Gallery of A rt ,Wa s h i n g t o n . Images in this guide are ©1997 Estate of Pa blo Picasso / A rtists Rights Society (ARS), New Yo rk PICASSO:The EarlyYears, 1892–1906 Pablo Picasso, one of the most he was gradually assimilated into their dynamic and influential artists of our stimulating intellectual community. century, achieved success in drawing, Although Picasso benefited greatly printmaking, sculpture, and ceramics from the artistic atmosphere in Paris as well as in painting. He experiment- and his circle of friends, he was often ed with a number of different artistic lonely, unhappy, and terribly poor. -

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Wings 0000-01 2:30-3:45PM Pre-Professional Program 0000-01 2:00-3:30PM Open Gym 0000-01 2:30-4:00PM Pre-Professional Program 0000-01 2:00-3:30PM Swinging Trapeze 1000-01 3:00-3:30PM 9:00 AM Swinging Trapeze 1000-01 3:00-3:30PM Bite Balance 1000-01 3:15-4:00PM Duo Trapeze 1000-03 3:30-4:15PM Chair Stacking 0100-01 3:15-4:00PM Hammock 0300-01 3:30-4:00PM Acrobatics 0105-02 ages 10+ 3:00 PM 3:00 Audition Preparation for Professional Circus Schools 0000-01 3:30-4:30PM Mexican Cloud Swing 0000-01 3:15-4:00PM Pre-Professional Program 0000-01 Shoot-Thru Ladder 0200-02 3:30-4:15PM Swinging Trapeze 0000-03 3:30-4:00PM Flying Trapeze Recreational 0000-01 4-Girl Spinning Cube 0100-01 3:45-4:15PM Handstands 1000-01 Globes 0000-01 Audition Preparation for Professional Circus Schools 0000-01 3:30-4:30PM Acrobatics 0105-01 ages 10+ Duo Trapeze 1000-03 3:30-4:15PM Shoot-Thru Ladder 0200-02 3:30-4:15PM Acrobatics 0225-02 Low Casting Fun 0000-04 4-Girl Spinning Cube 0100-01 3:45-4:15PM Chinese Poles 0050-02 Hammock 0100-01 4:00-4:30PM Double Trapeze 0000-01 4:15-5:00PM Bungee Trapeze 0200-01 Mini Hammock 0000-03 4:00 PM 4:00 Mexican Cloud Swing 0200-01 4:15-5:00PM Dance Ballet 1000-01 Duo Trapeze 1000-01 4:15-5:00PM Shoot-Thru Ladder 0200-01 4:15-5:00PM Duo Unicycle 1000-01 Star 0100-01 Triangle Trapeze 0100-03 4:15-5:00PM Globes 0000-02 Hammock 0200-01 4:30-5:00PM Acrobatics 0250-01 Mini Hammock 0000-02 Toddlers 0300-01 ages 4-5 Circus Experience for Parks and Rec 0000-01 4:30-5:00PM Handstands 0005-01 -

Impressionism and Post-Impressionism

09.10.2010 ART IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY: IMPRESSIONISM AND POST-IMPRESSIONISM Week 2 WORLD HISTORY ART HISTORY ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY Marx and Engels issue Communist Manifesto, 1848 Smirke finished British Museum Gold discovered in California 1849 The Stone Broker, Courbet 1850 Bibliotheque Sainte-Genevieve (Neo- Renaissance) 1852 The Third Class Carriage by Daumier Houses of Parliment, London (Neo-Gothic) 1854 Crystal Palace, First cast-iron and glass structure 1855 Courbet’s Pavillion of Realism Flaubert writes Madame Bovary 1856-1857 Mendel begins genetic experiments 1857 REALISM First oil well drilled, 1859-60 Red House by Philip Webb (Arts &Crafts) Darwin publishes Origin of Spaces Steel developed 1860 Snapshot photography developed U.S. Civil War breaks out 1861 Corot Painted Orpheus Leading Eurydice 1862 Garnier built Paris Opera (Neo-Baraque) Lincoln abolishes slavery 1863 Manet painted Luncheon on the Grass Suez Canal built 1869 Prussians besiege Paris 1871 1873 First color photos appear IMPRESSIONISM 1874 Impressionists hold first group show Custer defeated at Little Big Horn, 1876 Bell patents telephone Edison invents electric light 1879 1880 VanGogh begins painting career Population of Paris hits 2,200,000 1881 1882 Manet painted A Bar at the Folies-Bergère 1883 Monet settles at Giverny First motorcar built 1885 First Chicago Skyscraper built 1886 Impressionists hold last group show 1888 Portable Kodak camera perfected Hitler born 1889 Eiffel Tower built 1901 1902 1903 POSTIMPRESSIONISM 1905 1 09.10.2010 REALISM VALUES: Real , Fair, Objective INSPIRATION: The Machine Age, Marx and Engel’s Communist Manifesto, Photography, Renaissance art TONE: Calm, rational, economy of line and color SUBJECTS: Facts of the modern world, as the artist experienced them; Peasants and the urban working class; landcape; Serious scenes from ordinary life, mankind. -

Pittura Ideista: the Spiritual in Divisionist Painting1

Pittura ideista: The Spiritual in Divisionist Painting1 Vivien Greene The Divisionists were a loosely associated group of late-nineteenth-century painters intent on creating a distinctly Italian avant-garde art. Their mission was underpinned by modernist and nationalist aspirations,2 while their painting method drew on scientific theories of optics and chromatics and relied on the application of brushstrokes of individual, often complementary, colors to craft shimmering surfaces that capitalized on light effects.3 Although the movements’ members generally aligned I am grateful to those who read this essay: firstly, at its inception, Giovanna Ginex, more recently, Jon Snyder, and, lastly, my anonymous readers. I am also thankful to all my colleagues at the museums and archives named herein who gave me access to artworks and documents and supported my research efforts, even long distance. 1 This article is a recast and expanded version of an earlier essay of mine, “Divisionism’s Symbolist Ascent,” in Radical Light: Italy’s Divisionist Painters, 1891-1910 (exh. cat.), ed. Simonetta Fraquelli (London: National Gallery; Zurich: Kunsthaus Zurich, 2008), 47-59. My title borrows from a term that the Divisionist artist and critic Vittore Grubicy De Dragon developed to differentiate Italian Symbolism from similar tendencies among other artists and in other nations, calling it pittura ideista. See especially Vittore Grubicy De Dragon, “Pittura Ideista,” in Prima esposizione triennale Brera 1891. Tendenze evolutive nelle arti plastiche: Pensiero italiano 9 (Milan: Tipografia Cooperativa Insubria, 1891), 47-50. Grubicy’s moniker was probably inspired by G.-Albert Aurier’s concept of “art idéiste,” a term bandied about then, which was most famously discussed in his “Le Symbolisme en peinture: Paul Gauguin,” Mercure de France 2 (March 1891): 155-64. -

(At the Cirque Fernando) by Henri Toulouse-Lautrec

Equestrienne (At the Circus Fernando) 1887–1888 By Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO Department of Museum Education Division of Teacher Programs Crown Family Educator Resource Center Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec enjoyed breaking the rules. When Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec he came across an idea that interested him, he tried it—re- gardless of whether it was acceptable or not. Toulouse-Lautrec loved life and took inspiration from everything he came across. As a young man, he became interested in the circus and in Equestrienne (At the circus performers, and when a fellow artist showed him how to look at subjects as if they were cut off or “cropped” like a Circus Fernando) photograph, he took up that idea as well.1 Painted when he was only 24 years old, Equestrienne (At the Circus Fernando) 1887-1888 became one of his most well-known works. Oil on Canvas, 100.3 x 161.3 cm (39.5" x63.5") Toulouse-Lautrec: Childhood and Training As his name implies, Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse- Joseph Winterbotham Collection, 1925.523 Lautrec-Montfa was born into a wealthy family on November 24, 1864. As a young child, his parents were aware that his physical development was not normal as he often was ill, his leg bones broke easily, his speech was unclear, and he didn’t grow taller as he aged. Discussing Toulouse-Lautrec’s condition in 1994, biographer Julia Frey calls it congenital (something he was essentially born with) and states, “Although posthumous diagnosis is always risky, experts on endocrine disorders say that Henry was probably suffering from a genetic mishap which caused fragility at the growth end of the bones, hindering normal bone development and causing pain, deformation and weakness in the skeletal structure.”2 She adds, “As he entered adolescence, Henry’s long bones began to atrophy at the joints where the adolescent growth spurt would typically manifest itself.”3 His cousins also showed such symptoms, making this a genetic defect within the family. -

A Bouquet of Five Art Movements a Crash Course in 19Th & 20Th Century Art Movements and Using Its Inspiration to Paint Flowers

A Bouquet Of Five Art Movements A crash course in 19th & 20th century art movements and using its inspiration to paint flowers. Did you know that according to Wikipedia there are over 180 art movements? For this week’s project we are going to spend time looking at just 5 of these movements and these were hugely influential during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. They are: Day 1 - Impressionism Day 2 - Fauvism Day 3 - Cubism Day 4 - Abstract art Day 5 - Pop Art Day 6 challenge to create a picture for a Contactless Creativity group painting in the style of your preferred art movement Each day I will give you a little background information on the day’s art movement and its styles of painting. Then the task will be to create your own painting in the style of the art movement. The overall theme for the pictures is Flowers, however, if you have an alternative subject then you are very welcome to use that. At the end of the week the plan is for you to do a picture of a flower in your preferred art movement style and then pass it back to the Corn Exchange volunteer when they pick up your pack for it to be placed together to make a large piece of wonderful Contactless Creativity art work to be displayed somewhere at the Corn Exchange. A wonderful picture of loads of bright and colourful flowers will surely cheer us all up after lockdown! Materials For this week, I have provided you with simple materials: ❖ A couple of pencils and pencil sharpener ❖ A couple of paint brushes ❖ Tin of watercolours ❖ A4 sketchbook for you to keep.