(At the Cirque Fernando) by Henri Toulouse-Lautrec

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AN ANALYTICAL STUDY of P. A. RENOIRS' PAINTINGS Iwasttr of Fint Girt

AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF P. A. RENOIRS' PAINTINGS DISSERTATION SU8(N4ITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIfJIMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF iWasttr of fint girt (M. F. A.) SABIRA SULTANA '^tj^^^ Under the supervision of 0\AeM'TCVXIIK. Prof. ASifl^ M. RIZVI Dr. (Mrs) SIRTAJ RlZVl S'foervisor Co-Supei visor DEPARTMENT OF FINE ART ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1997 Z>J 'Z^ i^^ DS28S5 dedicated to- (H^ 'Parnate ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY CHAIRMAN DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS ALIGARH—202 002 (U.P.), INDIA Dated TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN This is to certify that Sabera Sultana of Master of Fine Art (M.F.A.) has completed her dissertation entitled "AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF P.A. RENOIR'S PAINTINGS" under the supervision of Prof. Ashfaq M. Rizvi and co-supervision of Dr. (Mrs.) Sirtaj Rizvi. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work is based on the investigations made, data collected and analysed by her and it has- not been submitted in any other university or Institution for any degree. Mrs. SEEMA JAVED Chairperson m4^ &(Mi/H>e& of Ins^tifHUion/, ^^ui'lc/aace' cm^ eri<>ouruae/riefity: A^ teacAer^ and Me^^ertHs^^r^ o^tAcsy (/Mser{xUlafi/ ^rof. £^fH]^ariimyrio/ar^ tAo las/y UCM^ accuiemto &e^£lan&. ^Co Aasy a€€n/ kuid e/KHc^ tO' ^^M^^ me/ c/arin^ tA& ^r€^b<ir<itlan/ of tAosy c/c&&erla6iafi/ and Aasy cAecAe<l (Ao contents' aMd^yormM/atlan&^ arf^U/ed at in/ t/ie/surn^. 0A. Sirta^ ^tlzai/ ^o-Su^benn&o^ of tAcs/ dissertation/ Au&^^UM</e^m^o If^fi^^ oft/us dissertation/, ^anv l>eAo/den/ to tAem/ IhotA^Jrom tAe/ dee^ o^nu^ l^eut^. -

Paul Gauguin 8 February to 28 June 2015

Media Release Paul Gauguin 8 February to 28 June 2015 With Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), the Fondation Beyeler presents one of the most important and fascinating artists in history. As one of the great European cultural highlights in the year 2015, the exhibition at the Fondation Beyeler brings together over fifty masterpieces by Gauguin from leading international museums and private collections. This is the most dazzling exhibition of masterpieces by this exceptional, groundbreaking French artist that has been held in Switzerland for sixty years; the last major retrospective in neighbouring countries dates back around ten years. Over six years in the making, the show is the most elaborate exhibition project in the Fondation Beyeler’s history. The museum is consequently expecting a record number of visitors. The exhibition features Gauguin’s multifaceted self-portraits as well as the visionary, spiritual paintings from his time in Brittany, but it mainly focuses on the world-famous paintings he created in Tahiti. In them, the artist celebrates his ideal of an unspoilt exotic world, harmoniously combining nature and culture, mysticism and eroticism, dream and reality. In addition to paintings, the exhibition includes a selection of Gauguin’s enigmatic sculptures that evoke the art of the South Seas that had by then already largely vanished. There is no art museum in the world exclusively devoted to Gauguin’s work, so the precious loans come from 13 countries: Switzerland, Germany, France, Spain, Belgium, Great Britain (England and Scotland), -

Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern

Lauren Jimerson exhibition review of Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 1 (Spring 2020) Citation: Lauren Jimerson, exhibition review of “Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern ,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw. 2020.19.1.14. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License Creative Commons License. Jimerson: Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 1 (Spring 2020) Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern Grand Palais, Paris October 9, 2019–January 27, 2020 Catalogue: Stéphane Guégan ed., Toulouse-Lautrec: Résolument moderne. Paris: Musée d’Orsay, RMN–Grand Palais, 2019. 352 pp.; 350 color illus.; chronology; exhibition checklist; bibliography; index. $48.45 (hardcover) ISBN: 978–2711874033 “Faire vrai et non pas idéal,” wrote the French painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864– 1901) in a letter to his friend Étienne Devismes in 1881. [1] In reaction to the traditional establishment, constituted especially by the École des Beaux-Arts, the Paris Salon, and the styles and techniques they promulgated, Toulouse-Lautrec cultivated his own approach to painting, while also pioneering new methods in lithography and the art of the poster. He explored popular, even vulgar subject matter, while collaborating with vanguard artists, writers, and stars of Bohemian Paris. Despite his artistic innovations, he remains an enigmatic and somewhat liminal figure in the history of French modern art. -

Renoir, Impressionism, and Full-Length Painting

FIRST COMPREHENSIVE STUDY OF RENOIR’S FULL-LENGTH CANVASES BRINGS TOGETHER ICONIC WORKS FROM EUROPE AND THE U.S. FOR AN EXCLUSIVE NEW YORK CITY EXHIBITION RENOIR, IMPRESSIONISM, AND FULL-LENGTH PAINTING February 7 through May 13, 2012 This winter and spring The Frick Collection presents an exhibition of nine iconic Impressionist paintings by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, offering the first comprehensive study of the artist’s engagement with the full-length format. Its use was associated with the official Paris Salon from the mid-1870s to mid- 1880s, the decade that saw the emergence of a fully fledged Impressionist aesthetic. The project was inspired by Renoir’s La Promenade of 1875–76, the most significant Impressionist work in the Frick’s permanent collection. Intended for public display, the vertical grand-scale canvases in the exhibition are among the artist’s most daring and ambitious presentations of contemporary subjects and are today considered masterpieces of Impressionism. The show and accompanying catalogue draw on contemporary criticism, literature, and archival documents to explore the motivation behind Renoir’s full-length figure paintings as well as their reception by critics, peers, and the public. Recently-undertaken technical studies of the canvases will also shed new light on the artist’s working methods. Works on loan from international institutions are La Parisienne from Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), Dance at Bougival, 1883, oil on canvas, 71 5/8 x 38 5/8 inches, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Picture Fund; photo: © 2012 Museum the National Museum Wales, Cardiff; The Umbrellas (Les Parapluies) from The of Fine Arts, Boston National Gallery, London (first time since 1886 on view in the United States); and Dance in the City and Dance in the Country from the Musée d’Orsay, Paris. -

Art of Life: Gauguin’S Language of Color and Shape Eva Maria Raepple College of Dupage, [email protected]

College of DuPage [email protected]. Philosophy Scholarship Philosophy 10-1-2011 Art of Life: Gauguin’s Language of Color and Shape Eva Maria Raepple College of DuPage, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.cod.edu/philosophypub Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Raepple, Eva Maria, "Art of Life: Gauguin’s Language of Color and Shape" (2011). Philosophy Scholarship. Paper 27. http://dc.cod.edu/philosophypub/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy at [email protected].. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Scholarship by an authorized administrator of [email protected].. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Art of Life: Gauguin’s Language of Color and Shape “Where the tree of knowledge stands, there is always Paradise”: thus speak the oldest and the youngest serpents. (Nietzsche. Beyond Good and Evil. Aphorisms. 152) Friedrich Nietzsche, the nineteenth century philosopher (1844 -1900), whose works speak of his unyielding search for an art of life, warns of the serpent’s promise, a promise that according to Genesis 3 foreshadows tribulations.1 On the stage of life the promise to know, to know as a subject that actively grasps the world, is an alluring, call, one that permits free spirits to explore and design life as a work of art beyond the confines of the herd.2 A changing role of the knowing and imagining subject in the nineteenth century enticed philosophers and inspired artists, unleashing their creativeness to explore new modes of writing and painting. -

Famous Impressionist Artists Chart

Impressionist Artist 1 of the Month Name: Nationality: Date Born:________Date Died:________ Gallery: ©Nadene of http://practicalpages.wordpress.com January 2010 2 Famous Impressionist Artist Edgar Degas Vincent Van Gogh Georges Seurat Paul Cezanne Claude Monet Henri de ToulouseToulouse----LautrecLautrec PierrePierre----AugusteAuguste Renoir Paul Gauguin Mary Cassatt Paul Signac Alfred Sisley Camille Pissarro Bertha Morisot ©Nadene of http://practicalpages.wordpress.com January 2010 3 Edgar Degas Gallery: Little Dancer of Fourteen Years , Ballet Rehearsal, 1873 Dancers at The Bar The Singer with glove Edgar Degas (19 July 1834 – 27 September 1917), born HilaireHilaire----GermainGermainGermain----EdgarEdgar De GasGas, was a French artist famous for his work in painting , sculpture , printmaking and drawing . He is regarded as one of the founders of Impressionism although he rejected the term, and preferred to be called a realist. [1] A superb draughtsman , he is especially identified with the subject of the dance, and over half his works depict dancers. Early in his career, his ambition was to be a history painter , a calling for which he was well prepared by his rigorous academic training and close study of classic art. In his early thirties, he changed course, and by bringing the traditional methods of a history painter to bear on contemporary subject matter, he became a classical painter of modern life. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edgar_Degas ©Nadene of http://practicalpages.wordpress.com January 2010 4 Vincent Van Gogh Gallery: Bedroom in Arles The Starry Night Wheat Field with Cypresses Vincent Willem van Gogh (30 March 1853 – 29 July 1890) was a Dutch Post-Impressionist painter whose work had a far-reaching influence on 20th century art for its vivid colors and emotional impact. -

TOULOUSE-LAUTREC PS Toulouse Lautrect 4CENG New.Qxp P-5 15 Jun7/4/2007 07.Qxp 11:39 7/26/2007 AM Page 5:45 2 PM Page 2

TOULOUSE-LAUTREC PS Toulouse Lautrect 4CENG new.qxp P-5 15 Jun7/4/2007 07.qxp 11:39 7/26/2007 AM Page 5:45 2 PM Page 2 Layout: Baseline Co. Ltd. 127-129A Nguyen Hue Fiditourist Building, 3rd Floor District 1, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. © Sirrocco, London, UK (English version) © Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification. ISBN: 978-1-78042-440-8 PS Toulouse Lautrect 4CENG new.qxp P-5 15 Jun7/4/2007 07.qxp 11:39 25/06/2007 AM Page 3:12 3 PM Page 3 Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec PS Toulouse Lautrect 4C new.qxp 7/4/2007 11:39 AM Page 4 4 PS Toulouse Lautrect 4CENG new.qxp P-5 15 Jun7/4/2007 07.qxp 11:39 7/26/2007 AM Page 3:34 5 PM Page 5 ou know, if one were a Frenchman, or dead, or a pervert – best of all, a dead French pervert – it might be possible to enjoy life!’ laments frustrated and ‘Yunsuccessful artist in an illustration in the German satirical magazine Simplicissimus issued in 1910. He is endeavouring to paint while his domestic life crowds in on him from every direction: children run about screaming, toys lie scattered on the floor, and his wife is hanging up washing on a line stretched across his studio. -

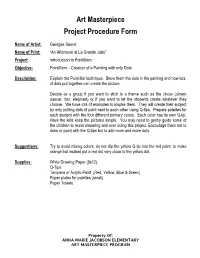

Art Masterpiece Project Procedure Form

Art Masterpiece Project Procedure Form Name of Artist: Georges Seurat Name of Print: “An Afternoon at La Grande Jatte” Project: Introduction to Pointillism Objective: Pointillism – Creation of a Painting with only Dots Description: Exlplain the Pointillist technique. Show them the dots in the painting and how lots of dots put together can create the picture. Decide as a group if you want to stick to a theme such as the circus (clowm dancer, lion, elephant) or if you want to let the students create whatever they choose. We have lots of examples to inspire them. They will create their subject by only putting dots of paint next to each other using Q-tips. Prepare palettes for each student with the four different primary colors. Each color has its own Q-tip. Have the kids keep the pictures simple. You may need to gently guide some of the children to resist smearing and over doing this project. Encourage them not to draw or paint with the Q-tips but to add more and more dots. Suggestions: Try to avoid mixing colors, do not dip the yellow Q-tip into the red paint, to make orange but instead put a red dot very close to the yellow dot. Supplies: White Drawing Paper (9x12) Q-Tips Tempera or Acrylic Paint (Red, Yellow, Blue & Green) Paper plates for palettes (small) Paper Towels Property Of: ANNA MARIE JACOBSON ELEMENTARY ART MASTERPIECE PROGRAM Georges Seurat (Zhorzh Soo-Rah) Seurat was born in 1859 in Paris. He was the son of a comfortably situated middle class family. -

Paul Gauguin

Paul Gauguin Painter, Sculptor 1848 – 1903 • Born on June 7, 1848 in Paris, france • Mother was peruvian, family lived Peru for 4 years • Family returns to France when he is 7 • Serves in the Merchant Marine, then the French Navy • Returns to Paris and becomes a Stockbroker • Marries a danish woman and they have 5 children • They live in Copenhagen where he is a stockbroker • Paints in his free time – buys art in galleries and makes friends with artists Portrait of Madame Gauguin • Decides he wants to (1880) paint full time – leaves his family in Copenhagen and goes back to Paris • His early work is in the impressionist style which is very popular at that time • He is not very successful at his art, he is poor • Leaves France to find a simpler life on a tropical island Aline Gauguin Brothers (1883) Visits his friend Vincent vanGogh in Arles, France where they both paint They quarrel, with van Gogh famously cutting off part of his ! own ear Gauguin leaves france and never sees van Gogh again Night Café at Arles (1888) Decides he doesn’t like impressionism, prefers native art of africa and asia because it has more meaning (symbolism) He paints flat areas of color and bold outlines He lives in Tahiti and The Siesta (1892) paints images of Polynesian life Tahitian women on the beach (1891) • His art is in the Primitivist style- exaggerated body proportions, animal symbolism, geometric designs and bold contrasting colors • Gauguin is the first artist of his time to become successful with this style (so different from the popular impressionism) • His work influences other painters, especially Pablo Picasso When do you get married? (1892) Gauguin spent the remainder of his life painting and living ! in the Marquesas Islands, a very remote, jungle-like ! place in French Polynesia (close to Tahiti) Gauguin’s house, Atuona, ! Marquesas Islands Gauguin lived ! alone in the ! jungle, where ! one day his houseboy arrived to find him dead, with a smile on his face. -

Pablo Picasso, One of the Most He Was Gradually Assimilated Into Their Dynamic and Influential Artists of Our Stimulating Intellectual Community

A Guide for Teachers National Gallery of Art,Washington PICASSO The Early Ye a r s 1892–1906 Teachers’ Guide This teachers’ guide investigates three National G a l l e ry of A rt paintings included in the exhibition P i c a s s o :The Early Ye a rs, 1 8 9 2 – 1 9 0 6.This guide is written for teachers of middle and high school stu- d e n t s . It includes background info r m a t i o n , d i s c u s s i o n questions and suggested activities.A dditional info r m a- tion is available on the National Gallery ’s web site at h t t p : / / w w w. n g a . gov. Prepared by the Department of Teacher & School Programs and produced by the D e p a rtment of Education Publ i c a t i o n s , Education Division, National Gallery of A rt . ©1997 Board of Tru s t e e s , National Gallery of A rt ,Wa s h i n g t o n . Images in this guide are ©1997 Estate of Pa blo Picasso / A rtists Rights Society (ARS), New Yo rk PICASSO:The EarlyYears, 1892–1906 Pablo Picasso, one of the most he was gradually assimilated into their dynamic and influential artists of our stimulating intellectual community. century, achieved success in drawing, Although Picasso benefited greatly printmaking, sculpture, and ceramics from the artistic atmosphere in Paris as well as in painting. He experiment- and his circle of friends, he was often ed with a number of different artistic lonely, unhappy, and terribly poor. -

Post-Impressionism and the Late Nineteenth Century College, Cambridge

164. Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Apples, c. 1875-77. Oil on canvas, 19.1 x 27.3. King’s Post-Impressionism and the Late Nineteenth Century College, Cambridge The term post-Impressionism, meaning “After Impressionism,” designates the work of Life with Apples (fig. 164), of c. certain late 19th-century painters, whose diverse styles were significantly influenced 1875-77, painted at the height of by Impressionism. Like the Impressionists, the Post-Impressionists were drawn to his Impressionist period, Cézanne bright color and visible, distinctive brushstrokes. But Post-Impressionist forms do not subordinates narrative to form. He dissolve into the medium and their edges. whether outlined or defined by sharp color condenses the rich thematic asso- separations, are relatively clear. ciations of the apple in Western im- Within Post-Impressionism two important trends evolved. These are exemplified on agery with a new structured abstrac- the one hand by Cézanne and Seurat, who reassert formal and structural values; and tion. Cézanne’s punning assertion on the other by Gauguin and van Gogh, who explore emotional content. Both trends that he wanted to “astonish Paris set the stage for major trends in early 20th-century art. Certain Post-Impressionist with an apple” [see Box] is nowhere artists were also influenced by the late 19th century Symbolist movement. more evident than in this work. Seven brightly colored apples are set on a slightly darker surface. Each is a sphere, outlined in black and built up with patches of color- Paul Cézanne reds, greens, yellows, and oranges-like the many facets of a crystal. -

Vangogh'sjapanandgauguin's Tahitireconsidered

“Van Gogh's Japan and Gauguin's Tahiti reconsidered,” Ideal Places East and West, International Research Center for Japanese Studies, March 31,1997, pp.153-177. Van Gogh's Japan and Gauguin's Tahiti Tahiti reconsidered Shigemi Shigemi INAGA Mie U University niversity INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM NO.l0 International International Research Center for Japanese]apanese Studies Idealld e al Places in HistoryHisto η - East and West - 1995 : 153-178153 -178 “Van Gogh's Japan and Gauguin's Tahiti reconsidered,” Ideal Places East and West, International Research Center for Japanese Studies, March 31,1997, pp.153-177. Van Gogh's Japan and Gauguin's Tahiti Tahiti reconsidered Shigemi INAGA Mie University If If the mountain paradise represents one type of ideal place place,, the other can be categorized categorized as the island paradise. Both in the East and in the WestWest, , it has been a common gardening practice to create an isle in the middle of a lake or a pond of a garden. garden. In JJapanese apanese the word island (“ (" shima") was literally a metonymical substitute for for the “"garden".garden". A small and isolated “"tops" tops" surrounded by water is a miniatur- miniatur ized ized version version,, or a regressive formform,, of the desire for marvelous possessions possessions,, to use Stephen Stephen Greenblatt's expression expression,, which prompted people to venture into the ocean in in search of hidden paradise. From the Greek Hesperides down to William Buttler Yeat's Yeat's Innisj Innisfree同e (or rather downdownto .to its parody as “"LakeLake Isles" in the “"Whispering Whispering Glades" Glades" by Evelyn Waugh in The Loved One [1948]),[1 948]) , the imagery of islands is abun-abun dant dant in Western literature.