A Digital Resource for Navigating Extended Techniques on Bass Clarinet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Julien Wilson: Improvisation and Timbral Manipulation on Selected Recordings with the Julien Wilson Trio

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2020 Julien Wilson: Improvisation and timbral manipulation on selected recordings with the Julien Wilson Trio Maximillian Wickham Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Wickham, M. (2020). Julien Wilson: Improvisation and timbral manipulation on selected recordings with the Julien Wilson Trio. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1546 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1546 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano by Maria Payan, M.M., B.M. A Thesis In Music Performance Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved Dr. Lisa Garner Santa Chair of Committee Dr. Keith Dye Dr. David Shea Dominick Casadonte Interim Dean of the Graduate School May 2013 Copyright 2013, Maria Payan Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project could not have started without the extraordinary help and encouragement of Dr. Lisa Garner Santa. The education, time, and support she gave me during my studies at Texas Tech University convey her devotion to her job. I have no words to express my gratitude towards her. In addition, this project could not have been finished without the immense help and patience of Dr. Keith Dye. For his generosity in helping me organize and edit this project, I thank him greatly. Finally, I would like to give my dearest gratitude to Donna Hogan. Without her endless advice and editing, this project would not have been at the level it is today. ii Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................. ii LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................. v 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ -

Contemporary Music Score Collection

UCLA Contemporary Music Score Collection Title Fragmente über das Marionettentheater Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6dx3b44v Author Santander, Gabriel Publication Date 2020 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Score in A440 Fragmente über das Marionettentheater para Nadia Trumpet in transposition kleine dramatische Burleske mit Texten von Heinrich v. Kleist Gabriel Santander für Sopran, Schalmei, Barocktrompete, Viola da Gamba und Gong SET UP SCHALMEI TROMPETE GAMBA TUNING: A = 440Hz for all. Trumpet is written in C flat transposition. Tuning of Gamba-Frets should be taken as reference until this A, for higher tones take the meantone tuning of Schalmei. Quarter-tones are to be found approximately half-way between the corresponding chromatic steps and should be unisono among all. SOPRAN TONBAND SCHALMEI / TROMPETE GONG Use a portable tape recorder * Metaformel 1: alternate grace note motives a, b, c (any order) with with a loud STOP button, scale fragments (any direction) in rhythmic groups of 4, 9, 2 (any order) record voice on tape once always legato and loud, fast tempo. A U D I E N C E context and timing are clear, * Metaformel 2: alternate grace note motives with rhythmic groups of non recording on several takes adjacent notes from scale, staccato / legato ad lib, fast tempo. GONG is possible as long as the * Metaformel 3: alternate grace note motives with isolated notes from scale final analog tape used for repeated in rhythmic groups of 8 / 6 or only once, always staccato, fast tempo. Gong hanging from frame, amplified through contact mic on performance is continuous. -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

Charles Ruggiero's "Tenor Attitudes": an Analytical Approach to Jazz

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2016 Charles Ruggiero's "Tenor Attitudes": An Analytical Approach to Jazz Styles and Influences Nicholas Vincent DiSalvio Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation DiSalvio, Nicholas Vincent, "Charles Ruggiero's "Tenor Attitudes": An Analytical Approach to Jazz Styles and Influences" (2016). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. CHARLES RUGGIERO’S “TENOR ATTITUDES”: AN ANALYTICAL APPROACH TO JAZZ STYLES AND INFLUENCES A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Nicholas Vincent DiSalvio B.M., Rowan University, 2009 M.M., Illinois State University, 2013 May 2016 For my wife Pagean: without you, I could not be where I am today. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my committee for their patience, wisdom, and guidance throughout the writing and revising of this document. I extend my heartfelt thanks to Dr. Griffin Campbell and Dr. Willis Delony for their tireless work with and belief in me over the past three years, as well as past professors Dr. -

Unit 10.2 the Physics of Music Objectives Notes on a Piano

Unit 10.2 The Physics of Music Teacher: Dr. Van Der Sluys Objectives • The Physics of Music – Strings – Brass and Woodwinds • Tuning - Beats Notes on a Piano Key Note Frquency (Hz) Wavelength (m) 52 C 524 0.637 51 B 494 0.676 50 A# or Bb 466 0.717 49 A 440 0.759 48 G# or Ab 415 0.805 47 G 392 0.852 46 F# or Gb 370 0.903 45 F 349 0.957 44 E 330 1.01 43 D# or Eb 311 1.07 42 D 294 1.14 41 C# or Db 277 1.21 40 C (middle) 262 1.27 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piano_key_frequencies 1 Vibrating Strings - Fundamental and Overtones A vibration in a string can L = 1/2 λ1 produce a standing wave. L = λ Usually a vibrating string 2 produces a sound whose L = 3/2 λ3 frequency in most cases is constant. Therefore, since L = 2 λ4 frequency characterizes the pitch, the sound produced L = 5/2 λ5 is a constant note. Vibrating L = 3 λ strings are the basis of any 6 string instrument like guitar, L = 7/2 λ7 cello, or piano. For the fundamental, λ = 2 L where Vibration, standing waves in a string, L is the length of the string. The fundamental and the first 6 overtones which form a harmonic series http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vibrating_string Length of Piano Strings The highest key on a piano corresponds to a frequency about 150 times that of the lowest key. If the string for the highest note is 5.0 cm long, how long would the string for the lowest note have to be if it had the same mass per unit length and the same tension? If v = fλ, how are the frequencies and length of strings related? Other String Instruments • All string instruments produce sound from one or more vibrating strings, transferred to the air by the body of the instrument (or by a pickup in the case of electronically- amplified instruments). -

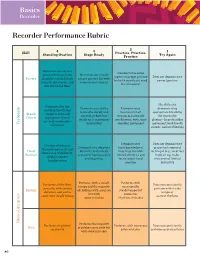

Recorder Performance Rubric

Basics Recorder Recorder Performance Rubric 2 Skill 4 3 Practice, Practice, 1 Standing Ovation Stage Ready Practice Try Again Demonstrates correct Demonstrates some posture with neck and Demonstrates mostly aspects of proper posture Does not demonstrate Posture shoulders relaxed, back proper posture but with but with significant need correct posture straight, chest open, and some inconsistencies for refinement feet flat on the floor Has difficulty Demonstrates low Demonstrates ability Demonstrates demonstrating and deep breath that to breathe deeply and inconsistent air appropriate breathing Breath supports even and control air flow, but stream, occasionally for successful Control appropriate flow of steady air is sometimes overblowing, with some playing—large shoulder air, with no shoulder Technique inconsistent shoulder movement movement, loud breath movement sounds, and overblowing Demonstrates Does not demonstrate Consistently fingers Demonstrates adequate basic knowledge of proper instrumental the notes correctly and Hand dexterity with mostly fingerings but with technique (e.g., incorrect shows ease of dexterity; Position consistent hand position limited dexterity and hand on top, holes displays correct and fingerings inconsistent hand not covered, limited hand position position dexterity) Performs with a steady Performs with Performs all rhythms Does not consistently tempo and the majority occasionally correctly, with correct perform with steady Rhythm of rhythms with accuracy steady tempo but duration, and with a tempo or but -

Expanding Horizons: the International Avant-Garde, 1962-75

452 ROBYNN STILWELL Joplin, Janis. 'Me and Bobby McGee' (Columbia, 1971) i_ /Mercedes Benz' (Columbia, 1971) 17- Llttle Richard. 'Lucille' (Specialty, 1957) 'Tutti Frutti' (Specialty, 1955) Lynn, Loretta. 'The Pili' (MCA, 1975) Expanding horizons: the International 'You Ain't Woman Enough to Take My Man' (MCA, 1966) avant-garde, 1962-75 'Your Squaw Is On the Warpath' (Decca, 1969) The Marvelettes. 'Picase Mr. Postman' (Motown, 1961) RICHARD TOOP Matchbox Twenty. 'Damn' (Atlantic, 1996) Nelson, Ricky. 'Helio, Mary Lou' (Imperial, 1958) 'Traveling Man' (Imperial, 1959) Phair, Liz. 'Happy'(live, 1996) Darmstadt after Steinecke Pickett, Wilson. 'In the Midnight Hour' (Atlantic, 1965) Presley, Elvis. 'Hound Dog' (RCA, 1956) When Wolfgang Steinecke - the originator of the Darmstadt Ferienkurse - The Ravens. 'Rock All Night Long' (Mercury, 1948) died at the end of 1961, much of the increasingly fragüe spirit of collegial- Redding, Otis. 'Dock of the Bay' (Stax, 1968) ity within the Cologne/Darmstadt-centred avant-garde died with him. Boulez 'Mr. Pitiful' (Stax, 1964) and Stockhausen in particular were already fiercely competitive, and when in 'Respect'(Stax, 1965) 1960 Steinecke had assigned direction of the Darmstadt composition course Simón and Garfunkel. 'A Simple Desultory Philippic' (Columbia, 1967) to Boulez, Stockhausen had pointedly stayed away.1 Cage's work and sig- Sinatra, Frank. In the Wee SmallHoun (Capítol, 1954) Songsfor Swinging Lovers (Capítol, 1955) nificance was a constant source of acrimonious debate, and Nono's bitter Surfaris. 'Wipe Out' (Decca, 1963) opposition to himz was one reason for the Italian composer being marginal- The Temptations. 'Papa Was a Rolling Stone' (Motown, 1972) ized by the Cologne inner circle as a structuralist reactionary. -

The Creative Application of Extended Techniques for Double Bass in Improvisation and Composition

The creative application of extended techniques for double bass in improvisation and composition Presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music) Volume Number 1 of 2 Ashley John Long 2020 Contents List of musical examples iii List of tables and figures vi Abstract vii Acknowledgements viii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Historical Precedents: Classical Virtuosi and the Viennese Bass 13 Chapter 2: Jazz Bass and the Development of Pizzicato i) Jazz 24 ii) Free improvisation 32 Chapter 3: Barry Guy i) Introduction 40 ii) Instrumental technique 45 iii) Musical choices 49 iv) Compositional technique 52 Chapter 4: Barry Guy: Bass Music i) Statements II – Introduction 58 ii) Statements II – Interpretation 60 iii) Statements II – A brief analysis 62 iv) Anna 81 v) Eos 96 Chapter 5: Bernard Rands: Memo I 105 i) Memo I/Statements II – Shared traits 110 ii) Shared techniques 112 iii) Shared notation of techniques 115 iv) Structure 116 v) Motivic similarities 118 vi) Wider concerns 122 i Chapter 6: Contextual Approaches to Performance and Composition within My Own Practice 130 Chapter 7: A Portfolio of Compositions: A Commentary 146 i) Ariel 147 ii) Courant 155 iii) Polynya 163 iv) Lento (i) 169 v) Lento (ii) 175 vi) Ontsindn 177 Conclusion 182 Bibliography 191 ii List of Examples Ex. 0.1 Polynya, Letter A, opening phrase 7 Ex. 1.1 Dragonetti, Twelve Waltzes No.1 (bb. 31–39) 19 Ex. 1.2 Bottesini, Concerto No.2 (bb. 1–8, 1st subject) 20 Ex.1.3 VerDi, Otello (Act 4 opening, double bass) 20 Ex. -

The Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano (1988) by David Maslanka

THE SONATA FOR ALTO SAXOPHONE AND PIANO (1988) BY DAVID MASLANKA: AN ANALYTIC AND PERFORMANCE GUIDE. by CAMILLE LOUISE OLIN (Under the Direction of Kenneth Fischer) ABSTRACT In recent years, the Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by David Maslanka has come to the forefront of saxophone literature, with many university professors and graduate students aspiring to perform this extremely demanding work. His writing encompasses a range of traditional and modern elements. The traditional elements involved include the use of “classical” forms, a simple harmonic language, and the lyrical, vocal qualities of the saxophone. The contemporary elements include the use of extended techniques such as multiphonics, slap tongue, manipulation of pitch, extreme dynamic ranges, and the multitude of notes in the altissimo range. Therefore, a theoretical understanding of the musical roots of this composition, as well as a practical guide to approaching the performance techniques utilized, will be a valuable aid and resource for saxophonists wishing to approach this composition. INDEX WORDS: David Maslanka, saxophone, performer’s guide, extended techniques, altissimo fingerings. THE SONATA FOR ALTO SAXOPHONE AND PIANO (1988) BY DAVID MASLANKA: AN ANALYTIC AND PERFORMANCE GUIDE. by CAMILLE OLIN B. Mus. Perf., Queensland Conservatorium Griffith University, Australia, 2000 M.M., The University of Georgia, 2003 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2006 © 2007 Camille Olin All Rights Reserved THE SONATA FOR ALTO SAXOPHONE AND PIANO (1988) BY DAVID MASLANKA: AN ANALYTIC AND PERFORMANCE GUIDE. by CAMILLE OLIN Major ProfEssor: KEnnEth FischEr CommittEE: Adrian Childs AngEla JonEs-REus D. -

Why Do Singers Sing in the Way They

Why do singers sing in the way they do? Why, for example, is western classical singing so different from pop singing? How is it that Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballe could sing together? These are the kinds of questions which John Potter, a singer of international repute and himself the master of many styles, poses in this fascinating book, which is effectively a history of singing style. He finds the reasons to be primarily ideological rather than specifically musical. His book identifies particular historical 'moments of change' in singing technique and style, and relates these to a three-stage theory of style based on the relationship of singing to text. There is a substantial section on meaning in singing, and a discussion of how the transmission of meaning is enabled or inhibited by different varieties of style or technique. VOCAL AUTHORITY VOCAL AUTHORITY Singing style and ideology JOHN POTTER CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 IRP, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, United Kingdom 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia © Cambridge University Press 1998 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1998 Typeset in Baskerville 11 /12^ pt [ c E] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library library of Congress cataloguing in publication data Potter, John, tenor. -

Slap Tongue (Saxophone Pizzicato)

Excerpt from “Part IV: Extended Techniques for Saxophone” Writing for Saxophones: A Guide to the Tonal Palette of the Saxophone Family for Composers, Arrangers and Performers by Jay C. Easton, D.M.A. (for further excerpts and ordering information, please visit http://baxtermusicpublishing.com) • Slap Tongue (saxophone pizzicato) Slap tongue is a versatile and interesting effect that is available in four varieties: 1. “melodic” slap or pizzicato (clearly pitched): melodic “plucking” sound entire keyed range of horn (but not altissimo) Maximum tempo: 240 beats per minute Possible from p to f dynamics 2. “slap tone” (clearly pitched): melodic slap attack followed by normal tone Maximum tempo: 200 beats per minute Possible from p to f dynamics 3. “woodblock” slap (unpitched): soft, dry percussive sound Maximum tempo: 200 beats per minute Possible from p to mf dynamics 4. “explosive” slap or “open” slap (unpitched): loud percussive sound Maximum tempo: 70 beats per minute Possible from mf to ff dynamics Not all saxophonists know how to slap tongue but an increasing number are learning the technique. The “melodic” slap and “slap tone” are produced by holding the tongue against about 1/3 to 1/2 of the tip end of the reed surface – a centimeter or so – and creating a suction-cup effect between tongue and reed. This is accomplished by pulling the middle of the tongue slightly away from the reed while keeping the edges and tip of the tongue sealed tight against it. The tongue is then quickly released by pushing it forward and downward away from the reed, creating suction between the tongue and the reed; this tongue motion is accompanied by sudden slight impulse of air.