Salad Bowl LARDER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DESIGN REVIEW COMMITTEE AGENDA DATE: Tuesday, June 22, 2021 TIME: 1:00 P.M

DESIGN REVIEW COMMITTEE AGENDA DATE: Tuesday, June 22, 2021 TIME: 1:00 P.M. Eastern Time PLACE: Carl T. Langford Boardroom One Jeff Fuqua Boulevard, Orlando International Airport The Greater Orlando Aviation Authority will adhere to any guidelines or executive orders as established by local, state, or the federal government in which virtual meetings are permitted during certain circumstances. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines, and the Greater Orlando Aviation Authority’s ongoing focus on safety regarding events and meetings, seating at sunshine committee meetings will be limited according to space and social distancing. Attendance is on a first-come, first-served basis. The Aviation Authority is subject to federal mask mandates. Federal law requires wearing a mask at all times in and on the airport property. Failure to comply may result in removal and denial of re-entry. Refusing to wear a mask in or on the airport property is a violation of federal law; individuals may be subject to penalties under federal law. RECORDING SECRETARY PHONE NUMBER EMAIL ADDRESS Tara Ciaglia 407-825-4461 [email protected] ITEM 1 CONSIDERATION OF Barnie's Coffee & Tea T-S1388 in South Terminal C S. Smith CONSIDERATION OF Provisions by Cask & Larder and Cask & Larder Bar and ITEM 2 S. Smith Bits T-S1390 in South Terminal C ITEM 3 CONSIDERATION OF Wine Bar George T-S1391 in South Terminal C S. Smith ITEM 4 CONSIDERATION OF Sunshine Diner T-S1392 in South Terminal C S. Smith ITEM 5 CONSIDERATION OF Orlando Brewing Bar & Bites T-S1393 in South Terminal C S. -

FEVER 1793 VOCABULARY Bates Cajoling to Diminish Or Make Less Strong Persuading by Using Flattery Or Promises

FEVER 1793 VOCABULARY bates cajoling to diminish or make less strong persuading by using flattery or promises abhorred canteen hated; despised portable drinking flask addle-patted conceded dull-witted; stupid To acknowledge, often reluctantly, as being true, just, or proper; admit agile quick, nimble condolences expressions of sympathy almshouse a home for the poor, supported by charity or contracted (will be on quiz) public funds. to catch or develop an illness or disease anguish cherub Extreme mental distress a depiction of an angel apothecary delectable one who prepares and sells drugs for pleasing to the senses, especially to the medicinal purposes sense of taste; delicious arduous demure hard to do, requiring much effort quiet and modest; reserved baffled despair puzzled, confused the feeling that everything is wrong and nothing will turn out well bilious suffering from or suggesting a liver disorder destitute (will be on quiz) or gastric distress extremely poor; lacking necessities like food and shelter brandish (v.) to wave or flourish in a menacing or vigorous fashion devoured greedily eaten/consumed FEVER 1793 VOCABULARY discreetly without drawing attention gala a public entertainment marking a special event, a festive occasion; festive, showy dollop a blob or small amount of something gaunt very thin especially from disease or hunger dote or cold shower with love grippe dowry influenza; the flu money or property brought by a woman to her husband at marriage gumption courage and initiative; common sense droll comical in an odd -

Larder Beetle

Pest Control Information Sheet Larder Beetle Larder beetles are occasional pests of households where they feed on a wide variety of animal protein-based products. Common foods for these beetles include leather goods, hides, skins, dried fish, pet food, bacon, cheese and feathers. The adult beetles fly well and may be seen around the house, but infestations normally start either in kitchens where food scraps have built up, in birds’ nests or occasionally under floors where a rat or mouse has died. They rarely cause much damage in the home Appearance Adults (above) are 7-10 mm long, dark brown to black, with a lighter stripe across the back. The larvae (below) are worm-like, fairly hairy, dark brown in colour, and appear banded. They are 10-14 mm in length. Signs of Infestation Often the first indication of an infestation is finding the moulted skins of the larvae. However, sightings of several adults can also point to this. Biology Female beetle lays up to 200 eggs on a food source which hatch within a week. The larvae moult up to 5 or 6 times over a period of 5-8 weeks, the pupate and after 2-4 weeks the adult beetle hatches. The beetles can live up to 6 months. How fast each stage of the lifecycle completes depends on conditions. From egg to adult can be a little as 2 months, or as long as 12 months. Significance Larder beetles are serious pests in domestic kitchens, particularly around food cupboards, cookers (where they are attracted by grease or fat) and refrigerators. -

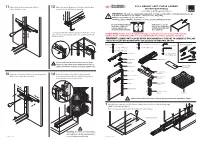

FULL HEIGHT SOFT CLOSE LARDER 11 Adjust Vertical Door Alignment with the 12 Adjust the Vertical Alignment of the Door with the Alen 3 Door Bracket Screws

FULL HEIGHT SOFT CLOSE LARDER 11 Adjust vertical door alignment with the 12 Adjust the vertical alignment of the door with the Alen 3 door bracket screws. screw located under the bottom runner. 300/400/500/600mm Assembly and fitting instructions IMPORTANT - The unit has a maximum loading limit of 100kg. Load should be evenly distributed across all trays with maximum load capacity for each tray not exceeding 16kg. No lubricant should be used on the runners. All fixings supplied MUST be used in the locations specified during installation. Wall For units 400mm wide and Unit must be securely above, two additional Additional fixed to the wall using a cabinet support legs legs suitable fixing bracket G should be fitted centrally. (not supplied). ‘Fine’ adjustment of the vertical alignment of the door can be achieved by compressing the stop cover and sliding towards PLEASE NOTE - Failure to use all supplied fittings according to instructions may void warranty. the front or rear. Handles must be mounted on the door in a central position in order to guarantee operation. WARNING! LARDER UNITS CAN BE HEAVY AND DANGEROUS. FAILURE TO CORRECTLY FOLLOW THESE INSTALLATION INSTRUCTIONS COULD LEAD TO PERSONAL INJURY. A x6 M6 washer D x6 M6 x 12mm countersunk screw Parts F x1 Alen key 2.5mm Tools required B x30 3.5 x 16mm screw E x3 M5 x 12mm screw G x1 Alen key 4mm C x6 M6 x 12mm screw Top runner x1 H x6 M5 Grub screw T (pre installed in frame) J K Stop spring x1 Bottom runner x1 Now refer back to instruction No. -

Village Level Production and Exchange in an Early State

The Village Larder: Village Level Production and Exchange in an Early State Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Klucas, Eric Eugene, 1957- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 21:26:36 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/565574 THE VILLAGE LARDER: VILLAGE LEVEL PRODUCTION AND EXCHANGE IN AN EARLY STATE by Eric Eugene Klueas A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 9 6 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA ® GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Final Examination Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by____ Eric Eugene Klucas______ entitled The Village Larder: Village Level Production and Exchange in an Early State _______ ~__________ ________ and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy__________ Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate's submission of the final copy of the dissertation to the Graduate College, I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement• 9y/7/f6 Dissertation Director Date 7 3 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This dissertation has been submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. -

1 Alexander Kitroeff Curriculum Vitae – May 2019 Current Position: Professor, History Department, Haverford College Educa

Alexander Kitroeff Curriculum Vitae – May 2019 History Department, Haverford College, 370 Lancaster Avenue, Haverford PA, 19041 Mobile phone: 610-864-0567 e-mail: [email protected] Current Position: Professor, History Department, Haverford College Education: D.Phil. Modern History, Oxford University 1984 M.A. History, University of Keele 1979 B.A. Politics, University of Warwick 1977 Research Interests: Identity in Greece & its Diaspora from politics to sport Teaching Fields: Nationalism & ethnicity in Modern Europe, Mediterranean, & Modern Greece C19-20th Professional Experience: Professor, Haverford College 2019-present Visiting Professor, College Year in Athens, Spring 2018 Visiting Professor, American College of Greece, 2017-18 Associate Professor, History Dept., Haverford College, 2002-2019 Assistant Professor, History Dept., Haverford College, 1996-2002 Assistant Professor, History Dept. & Onassis Center, New York University, 1990-96 Adjunct Assistant Professor, History Department, Temple University, 1989-90 Visiting Lecturer, History Dept., & Hellenic Studies, Princeton University, Fall 1988 Adj. Asst. Professor, Byz. & Modern Greek Studies, Queens College CUNY, 1986-89 Fellowships & Visiting Positions: Venizelos Chair Modern Greek Studies, The American College in Greece 2011-12 Research Fellow, Center for Byz. & Mod. Greek Studies, Queens College CUNY 2004 Visiting Scholar, Vryonis Center for the Study of Hellenism, Sacramento, Spring 1994 Senior Visiting Member, St Antony’s College, Oxford University, Trinity 1991 Major Research Awards & Grants: Selected as “12 Great Greek Minds at Foreign Universities” by News in Greece 2016 Jaharis Family Foundation, 2013-15 The Stavros S. Niarchos Foundation, 2012 Immigrant Learning Center, 2011 Bank of Piraeus Cultural Foundation, 2008 Proteus Foundation, 2008 Center for Neo-Hellenic Studies, Hellenic Research Institute, 2003 1 President Gerald R. -

Information Seeking Patterns of Ethnic Enclave Communities of Los Angeles: Sustainability Model for Mainstream Community Development

Information Seeking Patterns Of Ethnic Enclave Communities of Los Angeles: Sustainability Model For Mainstream Community Development Murali D. Nair, PhD Clinical Professor, School of Social Work University of Southern California E-mail [email protected] www.muralinair.com International Community Development Conference, Minneapolis Tuesday, July 26, 2016. 3:30 p.m. – 5:00 p.m. Nearly one-third of all foreign- born persons in the US live in California. Diversity of Los Angeles Los Angeles County is home to 10 million people—more than any other county in the U.S. It includes the City of Los Angeles and 87 other cities. City of Los Angeles has always had the region’s greatest ethnic diversity. Languages spoken • According to Professor Vyacheslav Ivanov of UCLA: there are at least 224 identified languages in Los Angeles County. Ethnic publications are locally produced in about 180 of these languages. Nearly 200 Languages being spoken 150 Publications in different languages As of 2012, nearly four-fifths of foreign- born Californians lived in the metropolitan areas of Los Angeles (5.1 million). Los Angeles hosts the largest populations of Cambodians, Iranians, Armenians, Belizeans, Bulgarians, Ethiopians, Filipinos, Guatemalans, Hungarians, Koreans, Mexicans, Salvadorans, Thais, and Pacific Islanders such as Samoans in both the U.S. and world outside of their respective countries. Los Angeles has one of the largest Native American populations in the country. The metropolitan area also is home to the second largest concentration of people of Jewish descent, after New York City. Los Angeles also has the second largest Nicaraguan community in the US after Miami. -

A Brief History of the Charlotte Fire Department

A Brief History of the Charlotte Fire Department The Volunteers Early in the nineteenth century Charlotte was a bustling village with all the commercial and manufacturing establishments necessary to sustain an agrarian economy. The census of 1850, the first to enumerate the residents of Charlotte separately from Mecklenburg County, showed the population to be 1,065. Charlotte covered an area of 1.68 square miles and was certainly large enough that bucket brigades were inadequate for fire protection. The first mention of fire services in City records occurs in 1845, when the Board of Aldermen approved payment for repair of a fire engine. That engine was hand drawn, hand pumped, and manned by “Fire Masters” who were paid on an on-call basis. The fire bell hung on the Square at Trade and Tryon. When a fire broke out, the discoverer would run to the Square and ring the bell. Alerted by the ringing bell, the volunteers would assemble at the Square to find out where the fire was, and then run to its location while others would to go the station, located at North Church and West Fifth, to get the apparatus and pull it to the fire. With the nearby railroad, train engineers often spotted fires and used a special signal with steam whistles to alert the community. They were credited with saving many lives and much property. The original volunteers called themselves the Hornets and all their equipment was hand drawn. The Hornet Company purchased a hand pumper in 1866 built by William Jeffers & Company of Pawtucket, Rhode Island. -

Industry, Transportation and Education

Industry, Transportation and Education The New South Development of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County Prepared by Sarah A. Woodard and Sherry Joines Wyatt David E, Gall, AIA, Architect September 2001 Introduction Purpose The primary objective of this report is to document and analyze the remaining, intact, early twentieth-century industrial and school buildings in Charlotte and Mecklenburg County and develop relevant contexts and registration requirements that will enable the Charlotte- Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission and the North Carolina Historic Preservation Office to evaluate the individual significance of these building types. Limits and Philosophy The survey and this report focus on two specific building types: industrial buildings and schools. Several of these buildings have already been listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Nevertheless, the increase in rehabilitation projects involving buildings of these types has necessitated the creation of contexts and registration requirements to facilitate their evaluation for National Register eligibility. The period of study was from the earliest resources, dating to the late nineteenth century, until c.1945 reflecting the large number of schools and industrial buildings recorded during the survey of Modernist resources in Charlotte, 1945 - 1965 (prepared by these authors in 2000). Developmental History From Settlement to the Civil War White settlers arrived in the Piedmont region of North Carolina beginning in the 1740s and Mecklenburg County was carved from Anson County in 1762. Charlotte, the settlement incorporated as the Mecklenburg county seat in 1768, was established primarily by Scots-Irish Presbyterians at the intersection of two Native American trade routes. These two routes were the Great Wagon Road leading from Pennsylvania and a trail that connected the backcountry of North and South Carolina with Charleston. -

Citizenship Under Siege Humanities in the Public Square VOL

VOL. 20, NO. 1 | WINTER 2017 CIVIC LEARNING FOR SHARED FUTURES A Publication of the Association of American Colleges and Universities Citizenship Under Siege Humanities in the Public Square VOL. 20, NO. 1 | WINTER 2017 KATHRYN PELTIER CAMPBELL, Editor TABLE OF CONTENTS BEN DEDMAN, Associate Editor ANN KAMMERER, Design 3 | From the Editor MICHELE STINSON, Production Manager DAWN MICHELE WHITEHEAD, Editorial Advisor Citizenship Under Siege SUSAN ALBERTINE, Editorial Advisor 4 | Diversity and the Future of American Democracy TIA BROWN McNAIR, Editorial Advisor WILLIAM D. ADAMS, National Endowment for the Humanities CARYN McTIGHE MUSIL, Senior Editorial 7 | Clashes Over Citizenship: Lady Liberty, Under Construction or On the Run? Advisor CARYN McTIGHE MUSIL, Association of American Colleges and Universities ANNE JENKINS, Senior Director for Communications 10 | Bridges of Empathy: Crossing Cultural Divides through Personal Narrative and Performance Advisory Board DONA CADY and MATTHEW OLSON—both of Middlesex Community College; and DAVID HARVEY CHARLES, University at Albany, PRICE, Santa Fe College State University of New York 13 | Affirming Interdependency: Interfaith Encounters through the Humanities TIMOTHY K. EATMAN, Rutgers University / Imagining America DEBRA L. SCHULTZ, Kingsborough Community College, City University of New York KEVIN HOVLAND, NAFSA: Association 16 | Addressing Wicked Problems through Deliberative Dialogue of International Educators JOHN J. THEIS, Lone Star College System, and FAGAN FORHAN, Mount Wachusett ARIANE HOY, -

Chinese Cambodian Refugees in the Washington Metropolitan Area

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing theUMI World’s Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Order Number 8820660 Family, ethnicity, and power: Chinese Cambodian refugees in the Washington metropolitan area Hackett, Beatrice Nied, Ph.D. The American University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by Hackett, Beatrice Nied. -

National Register of Historic Places Weekly Lists for 2014

National Register of Historic Places 2014 Weekly Lists National Register of Historic Places 2014 Weekly Lists ................................................................................ 1 January 3, 2014 ......................................................................................................................................... 3 January 10, 2014 ....................................................................................................................................... 9 January 17, 2014 ..................................................................................................................................... 16 January 24, 2014 ..................................................................................................................................... 24 January 31, 2014 ..................................................................................................................................... 29 February 7, 2014 ..................................................................................................................................... 34 February 14, 2014 ................................................................................................................................... 37 February 21, 2014 ................................................................................................................................... 43 February 28, 2014 ..................................................................................................................................