Village Level Production and Exchange in an Early State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DESIGN REVIEW COMMITTEE AGENDA DATE: Tuesday, June 22, 2021 TIME: 1:00 P.M

DESIGN REVIEW COMMITTEE AGENDA DATE: Tuesday, June 22, 2021 TIME: 1:00 P.M. Eastern Time PLACE: Carl T. Langford Boardroom One Jeff Fuqua Boulevard, Orlando International Airport The Greater Orlando Aviation Authority will adhere to any guidelines or executive orders as established by local, state, or the federal government in which virtual meetings are permitted during certain circumstances. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines, and the Greater Orlando Aviation Authority’s ongoing focus on safety regarding events and meetings, seating at sunshine committee meetings will be limited according to space and social distancing. Attendance is on a first-come, first-served basis. The Aviation Authority is subject to federal mask mandates. Federal law requires wearing a mask at all times in and on the airport property. Failure to comply may result in removal and denial of re-entry. Refusing to wear a mask in or on the airport property is a violation of federal law; individuals may be subject to penalties under federal law. RECORDING SECRETARY PHONE NUMBER EMAIL ADDRESS Tara Ciaglia 407-825-4461 [email protected] ITEM 1 CONSIDERATION OF Barnie's Coffee & Tea T-S1388 in South Terminal C S. Smith CONSIDERATION OF Provisions by Cask & Larder and Cask & Larder Bar and ITEM 2 S. Smith Bits T-S1390 in South Terminal C ITEM 3 CONSIDERATION OF Wine Bar George T-S1391 in South Terminal C S. Smith ITEM 4 CONSIDERATION OF Sunshine Diner T-S1392 in South Terminal C S. Smith ITEM 5 CONSIDERATION OF Orlando Brewing Bar & Bites T-S1393 in South Terminal C S. -

FEVER 1793 VOCABULARY Bates Cajoling to Diminish Or Make Less Strong Persuading by Using Flattery Or Promises

FEVER 1793 VOCABULARY bates cajoling to diminish or make less strong persuading by using flattery or promises abhorred canteen hated; despised portable drinking flask addle-patted conceded dull-witted; stupid To acknowledge, often reluctantly, as being true, just, or proper; admit agile quick, nimble condolences expressions of sympathy almshouse a home for the poor, supported by charity or contracted (will be on quiz) public funds. to catch or develop an illness or disease anguish cherub Extreme mental distress a depiction of an angel apothecary delectable one who prepares and sells drugs for pleasing to the senses, especially to the medicinal purposes sense of taste; delicious arduous demure hard to do, requiring much effort quiet and modest; reserved baffled despair puzzled, confused the feeling that everything is wrong and nothing will turn out well bilious suffering from or suggesting a liver disorder destitute (will be on quiz) or gastric distress extremely poor; lacking necessities like food and shelter brandish (v.) to wave or flourish in a menacing or vigorous fashion devoured greedily eaten/consumed FEVER 1793 VOCABULARY discreetly without drawing attention gala a public entertainment marking a special event, a festive occasion; festive, showy dollop a blob or small amount of something gaunt very thin especially from disease or hunger dote or cold shower with love grippe dowry influenza; the flu money or property brought by a woman to her husband at marriage gumption courage and initiative; common sense droll comical in an odd -

Larder Beetle

Pest Control Information Sheet Larder Beetle Larder beetles are occasional pests of households where they feed on a wide variety of animal protein-based products. Common foods for these beetles include leather goods, hides, skins, dried fish, pet food, bacon, cheese and feathers. The adult beetles fly well and may be seen around the house, but infestations normally start either in kitchens where food scraps have built up, in birds’ nests or occasionally under floors where a rat or mouse has died. They rarely cause much damage in the home Appearance Adults (above) are 7-10 mm long, dark brown to black, with a lighter stripe across the back. The larvae (below) are worm-like, fairly hairy, dark brown in colour, and appear banded. They are 10-14 mm in length. Signs of Infestation Often the first indication of an infestation is finding the moulted skins of the larvae. However, sightings of several adults can also point to this. Biology Female beetle lays up to 200 eggs on a food source which hatch within a week. The larvae moult up to 5 or 6 times over a period of 5-8 weeks, the pupate and after 2-4 weeks the adult beetle hatches. The beetles can live up to 6 months. How fast each stage of the lifecycle completes depends on conditions. From egg to adult can be a little as 2 months, or as long as 12 months. Significance Larder beetles are serious pests in domestic kitchens, particularly around food cupboards, cookers (where they are attracted by grease or fat) and refrigerators. -

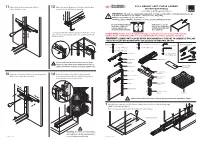

FULL HEIGHT SOFT CLOSE LARDER 11 Adjust Vertical Door Alignment with the 12 Adjust the Vertical Alignment of the Door with the Alen 3 Door Bracket Screws

FULL HEIGHT SOFT CLOSE LARDER 11 Adjust vertical door alignment with the 12 Adjust the vertical alignment of the door with the Alen 3 door bracket screws. screw located under the bottom runner. 300/400/500/600mm Assembly and fitting instructions IMPORTANT - The unit has a maximum loading limit of 100kg. Load should be evenly distributed across all trays with maximum load capacity for each tray not exceeding 16kg. No lubricant should be used on the runners. All fixings supplied MUST be used in the locations specified during installation. Wall For units 400mm wide and Unit must be securely above, two additional Additional fixed to the wall using a cabinet support legs legs suitable fixing bracket G should be fitted centrally. (not supplied). ‘Fine’ adjustment of the vertical alignment of the door can be achieved by compressing the stop cover and sliding towards PLEASE NOTE - Failure to use all supplied fittings according to instructions may void warranty. the front or rear. Handles must be mounted on the door in a central position in order to guarantee operation. WARNING! LARDER UNITS CAN BE HEAVY AND DANGEROUS. FAILURE TO CORRECTLY FOLLOW THESE INSTALLATION INSTRUCTIONS COULD LEAD TO PERSONAL INJURY. A x6 M6 washer D x6 M6 x 12mm countersunk screw Parts F x1 Alen key 2.5mm Tools required B x30 3.5 x 16mm screw E x3 M5 x 12mm screw G x1 Alen key 4mm C x6 M6 x 12mm screw Top runner x1 H x6 M5 Grub screw T (pre installed in frame) J K Stop spring x1 Bottom runner x1 Now refer back to instruction No. -

Furniture Brochure

Furniture Furniture solutions in movement solutions in movement Thomas Regout International B.V. offers a broad range of sliding solutions that help move your application in any direction: horizontal, vertical and diagonal. Our slides can be found in a wide range of applications in many market segments. In our long history we have grown into the company we are today: a major innovative player in automotive and industrial markets, as well as in furniture, professional storage and audio visual segments. We are continuously broadening our product range with new product groups, features and other solutions to fulfil your needs. Furniture In our own R&D department we design innovative sliding systems for different furniture applications. During the years we have gained a lot of experience and for that reason we can provide our customers with an extensive line of special features and telescopic slides with a high quality feeling. Besides Thomas Regout’s outstanding design capabilities for the wide range of products in the furniture markets, the company is also competent in designing complete customized systems. Our main focus is to be and to remain the best quality partner for our customers in mutual beneficial partnerships; partnerships that add value and power to your and our organization. Office furniture Kitchen furniture Shopfitting Furniture Furniture Ulf HD Titan Larder unit Finn Products Our wide range of sliding systems can be used in a lot of different Finn The Finn is a 2-beam cold rolled drawer slide applicable furniture applications. Our main products in this program are the for medium duty applications such as kitchen and bathroom Ulf HD, the Titan, Larder unit and the Finn slide. -

The Syrian Orthodox Church and Its Ancient Aramaic Heritage, I-Iii (Rome, 2001)

Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies 5:1, 63-112 © 2002 by Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Institute SOME BASIC ANNOTATION TO THE HIDDEN PEARL: THE SYRIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH AND ITS ANCIENT ARAMAIC HERITAGE, I-III (ROME, 2001) SEBASTIAN P. BROCK UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD [1] The three volumes, entitled The Hidden Pearl. The Syrian Orthodox Church and its Ancient Aramaic Heritage, published by TransWorld Film Italia in 2001, were commisioned to accompany three documentaries. The connecting thread throughout the three millennia that are covered is the Aramaic language with its various dialects, though the emphasis is always on the users of the language, rather than the language itself. Since the documentaries were commissioned by the Syrian Orthodox community, part of the third volume focuses on developments specific to them, but elsewhere the aim has been to be inclusive, not only of the other Syriac Churches, but also of other communities using Aramaic, both in the past and, to some extent at least, in the present. [2] The volumes were written with a non-specialist audience in mind and so there are no footnotes; since, however, some of the inscriptions and manuscripts etc. which are referred to may not always be readily identifiable to scholars, the opportunity has been taken to benefit from the hospitality of Hugoye in order to provide some basic annotation, in addition to the section “For Further Reading” at the end of each volume. Needless to say, in providing this annotation no attempt has been made to provide a proper 63 64 Sebastian P. Brock bibliography to all the different topics covered; rather, the aim is simply to provide specific references for some of the more obscure items. -

City of Brunswick Comprehensive Plan Update | 2019‐2023

City of Brunswick Comprehensive Plan Update | 2019‐2023 Table of Contents Chapter 1 – Introduction & Overview ............................................................................................. 1 Chapter 2 – Community Goals ........................................................................................................ 6 Chapter 3 – Needs and Opportunities ............................................................................................ 8 Chapter 4 – Economic Development ............................................................................................ 10 Chapter 5 – Land Use .................................................................................................................... 14 Character Area: North Brunswick ................................................................................................ 15 Chapter 6 – Transportation ........................................................................................................... 52 Chapter 7 – Housing ...................................................................................................................... 55 Chapter 8 – Stormwater ............................................................................................................... 56 Chapter 9 – Community Work Program ....................................................................................... 57 Chapter 10 – Summary ................................................................................................................. 58 Appendix -

Larder Beetle.Pub

CORNELL COOPERATIVE EXTENSION OF ONEIDA COUNTY 121 Second Street Oriskany, NY 13424-9799 (315) 736-3394 or (315) 337-2531 FAX: (315) 736-2580 Larder Beetle Dermestes lardatius L. Injury In the past, home stored meats and raw hides were frequently damaged by larder beetles. Modern meth- ods of meat storage and meat distribution have elimi- nated this food source for the beetle larvae. Presently, larder beetles are more of a nuisance pest, although they may attack some pantry products such as dried pet food. The occurrence of larder beetles in the home may be associated with the presence of a dead rodent— mouse, rat, chipmunk or squirrel—between walls of the house or in an attic or crawl space. Accumula- larder beetle tions of dead insects such as cluster flies in lamp Dermestes lardarius Linnaeus globes, between walls or attic windows may also Adult(s) support large numbers of larder beetles. Fledgling Photo by Joseph Berger birds or abandoned nests beneath the eaves or in an www.insectimages.org attic may attract larder beetles. Museum specimens, feathers, horn, hair, hides and beeswax along with dried meat or fish, biscuits or other dry pet food are susceptible to attack. Description and Life History Adult beetles are about 1/3 inch (8-10mm) long, dark brown in color for most of the body, interrupted by a broad, somewhat yellowish gray band across the front portion of the forewings. The band may show six darker spots. Adult beetles are sometimes observed outdoors where they have been feeding upon the pollen of flowers. -

AIA Bulletin, Fiscal Year 2005

ARCHAEOLOGICAL INSTITUTE OF AMERICA A I A B U L L E T I N Volume 96 Fiscal Year 2005 AIA BULLETIN, Fiscal Year 2005 Table of Contents GOVERNING BOARD Governing Board . 3 AWARD CITATIONS Gold Medal Award for Distinguished Archaeological Achievement . 4 Pomerance Award for Scientific Contributions to Archaeology . 5 Martha and Artemis Joukowsky Distinguished Service Award . 6 James R . Wiseman Book Award . 6 Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching Award . 7 Conservation and Heritage Management Award . 8 Outstanding Public Service Award . 8 ANNUAL REPORTS Report of the President . 10 Report of the First Vice President . 12 Report of the Vice President for Professional Responsibilities . 13 Report of the Vice President for Publications . 15 Report of the Vice President for Societies . 16 Report of the Vice President for Education and Outreach . 17 Report of the Treasurer . 19 Report of the Editor-in-Chief, American Journal of Archaeology . 24 Report of the Development Committee . 26 MINUTES OF MEETINGS Executive Committee: August 13, 2004 . 28 Executive Committee: September 10, 2004 . 32 Governing Board: October 16, 2004 . 36 Executive Committee: December 8, 2004 . 44 Governing Board: January 6, 2005 . 48 nstitute of America nstitute I 126th Council: January 7, 2005 . 54 Executive Committee: February 11, 2005 . 62 Executive Committee: March 9, 2005 . 66 Executive Committee: April 12, 2005 . 69 Governing Board: April 30, 2005 . 70 R 2006 LECTURES AND PROGRAMS BE M Special Lectures . 80 TE P AIA National Lecture Program . 81 E S 96 (July 2004–June 2005) Volume BULLETIN, the Archaeological © 2006 by Copyright 2 ARCHAEOLOgic AL INStitute OF AMERic A ROLL OF SPECIAL MEMBERS . -

Zuhrah Shrine Ceremonial – May 22Nd

JUNE 2010 VOLUME LXXXIII • NUMBER 6 MINNEAPOLIS, MINNESOTA • www.zuhrah.org Zuhrah Shrine Ceremonial – May 22nd 2 ZUHRAH ARABIAN JUNE 2010 ZUHRAH ARABIAN Zuhrah USPS 699-560 Stated 2540 Park Avenue, Minneapolis, MN 55404 Meeting TELEPHONE: 612-871-3555 Friday, June 11th FAX: 612-871-2632 WEB: www.zuhrah.org Time: 7:00 p.m. RSVP for dinner by JUNE 2010 Monday, June 7th All communications regarding the editorial content or advertising should be addressed to The Zuhrah Arabian, 2540 Park Avenue, Minneapolis, MN 55404. Entered as periodicals at Carlton, Minnesota, with additional mailing offices. Printed monthly at Carlton, Minnesota 55718. IN MEMORIAM Published at 2540 Park Avenue, Minneapolis, Minnesota. Subscription price, $12.00 a year. Send changes of Address to 2540 Park Avenue, Minneapolis, MN 55404. ZUHRAH SHRINE DIVAN ELECTED Potentate ..................................................Darryl Metzger (Linda) Chief Rabban...................................................Gary Sibben (Terri) Assistant Rabban .............................................Tony R. Krall (Bev) High Priest & Prophet.................................Al Neiderhaus (Deb) Oriental Guide.....................................Theodore M. Martz (Lori) Treasurer...................................................Timothy R. Jirak (Jami) Edward D Shimek Recorder ....................................Vyrl D.“Nib” Norby, PP (Peggy) Russel D Stauber Marvin Friedman APPOINTED Cedric M Bonner First Ceremonial Master ......................Ross E. Hjermstad (Deb) Robert W Apelt -

Understanding Racial Segregation

CULtivate. 100 Years and Counting: The Enduring Legacy of Racial Residential Segregation in Chicago in the Post-Civil Rights Era PART ONE: The Impact of Chicago’s Racial Residential Segregation on Residence,Housing and Transportation The Chicago Urban League March, 2016 Prepared by Stephanie Schmitz Bechteler, Director of Research and Evaluation The CULtivate Series The mission of the Chicago Urban League is to work for economic, educational and social progress for African Americans and promote strong, sustainable communities through advocacy, collaboration and innovation. Our work is guided by a strategic plan that outlines four key organizational goals, one of which is as follows: “Be a leader on issues impacting African-Americans.” Strategies under this goal include identifying and prioritizing key focal issues, conducting research and gathering information, building collaborative partnerships and advocating for social change. Beginning in early 2015, the Chicago Urban League began developing the CULtivate Series to ensure that our organization was actively pursuing a thought leadership role on behalf of the African-American community in Chicago. We wanted to commit our time and resources to examining a key issue or set of issues, disseminating our findings and recommendations and committing to action steps to begin addressing these issues.. Issues We’ll Explore Over the upcoming years, we’ll examine a range of issues impacting African-Americans, from business and economic development to educational equity, to public safety and criminal justice system issues and reform. At the start of each series, the Chicago Urban League leadership team will review the political, business and social landscapes nationally and in Chicago to identify a set of issues impacting African-Americans. -

INSTRUCTION MANUAL MODEL No.: PL167GWA 55Cm UNDER

55cm UNDER COUNTER LARDER INSTRUCTION MANUAL MODEL No.: PL167GWA Please read this instruction manual carefully before operation Keep these instructions in a safe place for future reference CONTENTS Getting to know your larder fridge 1 Safety Information 2 Installation 2 Electrical Connection 3 Operating your refrigerator 4 Setting the Thermostat Control 4 Defrosting the fridge 4 Storage of fresh food in the refrigerator 5 Cleaning your refrigerator 6 Replacing the lamp 6 Reversing the door 7 Maintenance 8 Trouble shooting 9 Prolonged off periods 11 Do’s and Don’ts 11 Technical data 13 Important disposal instructions 14 If something doens't seem to work 14 Getting to know your larder fridge 1. Top Cover 2. Cabinet 3. Shelves 4. Crisper Box Cover 5. Crisper Box 6. Levelling Legs 7. Bottle Racks 8. Door Storage Compartment 9. Recessed Door Handle 10. Temperature Control Knob/Lamp 11. Door switch Dear Customer: Thank you for buying a Proline Refrigerator. To ensure that you get the best results from your new refrigerator, please take time to read through the simple instructions in this manual. Please ensure that the packing material is disposed of in accordance with the current environmental requirements. Safety information This information is provided in the interest of your safety. Please read the following carefully before carrying out the installation or use of the refrigerator. If you are discarding an old refrigerator / chiller with a lock/catch fitted. Ensure that it is left in a safe condition with the lock / catch broken to prevent the entrapment of children. Old refrigerator equipment may contain CFC’s that will damage the ozone layer.