Industry, Transportation and Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

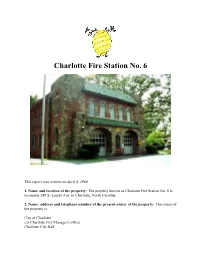

Charlotte Fire Station No. 6

Charlotte Fire Station No. 6 This report was written on April 4, 1988 1. Name and location of the property: The property known as Charlotte Fire Station No. 6 is located at 249 S. Laurel Ave. in Charlotte, North Carolina. 2. Name, address and telephone number of the present owner of the property: The owner of the property is: City of Charlotte c/o Charlotte City Manager's office Charlotte City Hall 600 E. Trade St. Charlotte, N.C. 28202 Telephone: 704/336-2241 The tenant of the building is the Charlotte Fire Department. For information contact: Mr. Robert Ellison Assistant Chief for Administration Charlotte Fire Department 125 S. Davidson St. Charlotte, N.C. 28202 Telephone: 704/336-2051 3. Representative photographs of the property: This report contains representative photographs of the property. 4. A map depicting the location of the property: This report contains a map which depicts the location of the property. Click on the map to browse 5. Current Deed Book Reference to the property: The most recent reference to this property is recorded in Mecklenburg Deed Book 717, Page 361. The Tax Parcel Number of the property is: 155-034-17. 6. A brief historical sketch of the property: This report contains a brief historical sketch of the property prepared by Dr. William H. Huffman, Ph.D. 7. A brief architectural description of the property: This report contains a brief architectural description of the property prepared by Joseph Schuchman. 8. Documentation of and in what ways the property meets the criteria for designation-set forth in N.C.G.S. -

A Brief History of the Charlotte Fire Department

A Brief History of the Charlotte Fire Department The Volunteers Early in the nineteenth century Charlotte was a bustling village with all the commercial and manufacturing establishments necessary to sustain an agrarian economy. The census of 1850, the first to enumerate the residents of Charlotte separately from Mecklenburg County, showed the population to be 1,065. Charlotte covered an area of 1.68 square miles and was certainly large enough that bucket brigades were inadequate for fire protection. The first mention of fire services in City records occurs in 1845, when the Board of Aldermen approved payment for repair of a fire engine. That engine was hand drawn, hand pumped, and manned by “Fire Masters” who were paid on an on-call basis. The fire bell hung on the Square at Trade and Tryon. When a fire broke out, the discoverer would run to the Square and ring the bell. Alerted by the ringing bell, the volunteers would assemble at the Square to find out where the fire was, and then run to its location while others would to go the station, located at North Church and West Fifth, to get the apparatus and pull it to the fire. With the nearby railroad, train engineers often spotted fires and used a special signal with steam whistles to alert the community. They were credited with saving many lives and much property. The original volunteers called themselves the Hornets and all their equipment was hand drawn. The Hornet Company purchased a hand pumper in 1866 built by William Jeffers & Company of Pawtucket, Rhode Island. -

Existing Floor Plans

a creative mixed-use district in west charlotte offering 285,000 sq ft of reclaimed industrial space in 8 distinct buildings on 30 acres MARKET & RETAIL EVENT VENUES KITCHEN INCUBATOR MAKERSPACE LOFT OFFICES FUTURE RESIDENCES A CLOSER LOOK ABOUT CHARLOTTE Carolina Panthers PARKS & GREENWAYS 2.5 MILLION CHARLOTTE DOUGLAS Charlotte Hornets colleges 7 FORTUNE 500 47 210 parks RESIDENTS (CSA) INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT Charlotte Knights & universities & GROWING the national hub of American COMPANIES Charlotte Checkers located on more than Airlines, is the 14th largest & US. National & nearly 21,000+ acres The Charlotte metro area’s of parkland population is projected to airport in the nation based 10 RANKED IN THE Whitewater Center 37 miles on passenger totals, the 31st 250,000 grow by 47% between FORTUNE 1000 Lowes Motor Speedway students of developed & 2010 & 2030 largest airport worldwide NASCAR Hall of Fame 150 miles Carowinds of undeveloped greenways in Mecklenburg County 1 To NoDa Seversville 5 Wesley 2 Heights 4 Uptown Charlotte 3 To Plaza Midwood South End IN CONTEXT 2 4 Proposed Greenway Johnson & Wales University Frazier Park Extension 1 Johnson C. Smith University 3 Bank of America Stadium 5 Start of Stewart Creek Greenway Lakewood Trolley SITE PLAN BUILDING SUMMARY 1 Savona Mill — ±199,150 sq. ft. 6 5 2 Building 2 — ±4,850 sq. ft. 3 Building 3 — ±19,900 sq. ft. 4 Building 4 — ±11,600 sq. ft. 5 7 Building 5 — ±6,750 sq. ft. 9 6 Building 6 — ±12,500 sq. ft. 7 Building 7 — ±22,970 sq. ft. 3 12 8 Blue Blaze Brewery — ±8,000 sq. -

CENTER CITY: the Business District and the Original Four Wards

THE CENTER CITY: The Business District and the Original Four Wards By Dr. Thomas W. Hanchett The history of Charlotte's Center City area is largely a story of what is no longer there. The grid of straight streets that lies within today's innermost expressway loop was the whole of Charlotte less than one hundred years ago. Today it contains a cluster of skyscrapers, three dozen residential blocks, and a vast area of vacant land with only scattered buildings. This essay will trace the Center City's development, then look at the significant pre-World War II structures remaining in each of the area's four wards. The Center City has experienced three distinct development phases as Charlotte has grown from a village to a town to a major city. In the first phase, the area was the entire village. It was what geographers term a "walking city," arranged for easy pedestrian movement with the richest residents living the shortest walk to the commercial core. This era lasted from settlement in 1753 through the 1880s. In 1891 the new electric trolley system transformed Charlotte into a "streetcar city" with new suburbs surrounding the old village. In the old Center City the commercial core expanded, clustered around the trolley crossroads at Independence Square. Residence continued to be important, and the area continued to grow in population, but now the wealthy moved outward to the suburbs and the middle class and poor moved inward. In the 1930s and 1940s the automobile replaced the trolley as Charlotte's prime people mover, and the Center City changed again. -

West Trade / Rozzelles Ferry Road Date: May 31, 2017

PLANNING REPORT COMPREHENSIVE NEIGHBORHOOD IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM FINAL REPORT WEST TRADE / ROZZELLES FERRY ROAD DATE: MAY 31, 2017 This program is part of the City of Charlotte’s Community Investment Plan. Learn more at www.CharlotteFuture.com. West Trade/Rozzelles Ferry CNIP Coordination Team Lamar Davis E&PM ES Project Manager, West Trade Rozzelles Ferry CNIP Stephen Bolt CDOT Fred Hunter Charlotte Works Julie Millea E&PM, Real Estate Alberto Gonzalez Planning, West Trade Rozzelles CNIP Gary King E&PM, Business Services Mike Carsno E&PM, ES Construction Craig Monroe Landscape Management Roy Ezell E&PM, ES Utilities Randy Harris N&BS, West Trade Rozzelles Ferry CNIP Jimmy Rhyne CDOT, Implementation Jeff Black CDOT, Street Maintenance John Keene E&PM, Storm water Brian Horton CATS Veronica Wallace West Strategy Team Lead Debbie Smith CDOT, West Trade Rozzelles Ferry CNIP Stephanie Roberts Mecklenburg County Stormwater Consulting Support Stantec Consulting Services Inc.: Mike Rutkowski (Project Manager), Matt Noonkester, Jeff Rice, Mike Lindgren, Scott Lane, Hagen Hammons, Ashley Bonawitz, Anthony Isley, Michelle Peele, Erin Convery, Sam Williams, Jaquasha Colón The Dodd Studio: Dan Dodd, Brandon Green and Anna Simpson W C T N PROCESS & INTENT 2 R I F P Page 05 USDG Process and Intent A brief overview of the Urban Street Design Guidelines and process Page 05 Purpose and Intent Page 05 Background and Prior Actions Page 07 Guiding Lights: The USDG Process Page 11 The Study Area Highlighting the context that shaped the actions of the Project -

Robert Charles Lesser & Co., Llc Commercial Market

ROBERT CHARLES LESSER & CO., LLC COMMERCIAL MARKET ANALYSIS TO SUPPORT PLANNING AND REVITALIZATION EFFORTS IN THE LAKEWOOD NEIGHBORHOOD; CHARLOTTE, NORTH CAROLINA Prepared for: CHARLOTTE NEIGHBORHOOD DEVELOPMENT - LAKEWOOD November 5, 2004 ATLANTA OFFICE • 999 PEACHTREE STREET, SUITE 2690 • ATLANTA, GA 30309 • TEL 404 365 9501 FAX 404 365 8363 CHARLOTTE NEIGHBORHOOD DEVELOPMENT - LAKEWOOD REPORT ROBERT CHARLES LESSER & CO., LLC CHARLOTTE NEIGHBORHOOD DEVELOPMENT - LAKEWOOD REPORT CONTENTS Page BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES.....................................................................................1 - 2 Background Engagement Objective and Methodology CRITICAL ASSUMPTIONS ...................................................................................................3 SUBJECT PROPERTY............................................................................................................4 - 7 Lakewood Neighborhood Strengths and Challenges Current Land Uses DEMOGRAPHIC AND ECONOMIC ANALYSIS ..................................................................8 - 10 Demographic Analysis Economic Analysis MARKET OVERVIEW...........................................................................................................11 - 24 Retail Office Residential Community and Civic Space SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS...........................................25 - 28 GENERAL LIMITING CONDITIONS....................................................................................29 Page i ROBERT CHARLES LESSER & CO., LLC 02-10055.00 -

History of Mecklenburg County and the City Of

2 THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL THE COLLECTION OF NORTH CAROLINIANA C971.60 T66m v. c.2 UNIVERSITY OF N.C. AT CHAPEL HILL 00015565808 This book is due on the last date stamped below unless recalled sooner. It may be renewed only once and must be brought to the North Carolina Collection for renewal. —H 1979 <M*f a 2288 *» 1-> .._ ' < JoJ Form No. A- 369 BRITISH MAP OF MECKLENBURG IN 1780. History of Mecklenburg County AND The City of Charlotte From 1740 to 1903. BY D. A. TOMPKINS, Author of Cotton and Cotton Oil; Cotton Mill, Commercial Features ; Cotton Values in Tex- Fabrics Cotton Mill, tile ; Processes and Calculations ; and American Commerce, Its Expansion. Charlotte, N. C, 1903. VOLUME TWO—APPENDIX. CHARLOTTE, N. C: Observer Printing House. 1903. COPYRIGHT, 1904. BY I). \. TOMPKINS. EXPLANATION. This history is published in two volumes. The first volume contains the simple narrative, and the second is in the nature of an appendix, containing- ample discussions of important events, a collection of biographies and many official docu- ments justifying and verifying- the statements in this volume. At the end of each chapter is given the sources of the in- formation therein contained, and at the end of each volume is an index. PREFACE. One of the rarest exceptions in literature is a production devoid of personal feeling. Few indeed are the men, who, realizing that the responsibility for their writings will be for them alone to bear, will not utilize the advantage for the promulgation of things as they would like them to be. -

Advanced Pedestrian Safety Using Education and Enforcement In

Advancing Pedestrian Safety Using Education and Enforcement In Pedestrian Focus Cities and States: North Carolina Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. DOT HS 812 286 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Advancing Pedestrian Safety Using Education and Enforcement Efforts June 2016 in Pedestrian Focus Cities and States: North Carolina 6. Performing Organization Code UNC Highway Safety Research Center 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Laura Sandt, James Gallagher, Dan Gelinne 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) University of North Carolina 11. Contract or Grant No. Highway Safety Research Center 730 MLK, Jr. Blvd. Suite 300, CB# 3430 DTNH22-09-H-00278 Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3430 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Draft Final Report 1200 New Jersey Avenue SE. Oct 2009 – Sept 2013 Washington, DC 20590 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes Supported by a grant from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration with additional funds from the North Carolina Department of Transportation. Several other current and former HSRC staff contributed to this effort, including Nancy Pullen-Seufert, Seth LaJeunesse, Max Bushell, Libby Thomas, Charlie Zegeer, Bill Hunter, Rob Foss, Laura Wagner, Jonathon Weisenfeld, Graham Russell, Mike Rogers, and Carol Martell. Credit goes to Nelson Holden, Artur Khalikov, Matt Evans, and Bryan Poole for their role in field data collection and entry. 16. Abstract The goal of this effort was to assist selected communities in North Carolina in implementing and evaluating education and enforcement activities. -

FINAL REPORT Charlotte Comprehensive Architectural

FINAL REPORT Charlotte Comprehensive Architectural Survey, Phase II Charlotte, North Carolina Prepared for: John G. Howard Charlotte Historic District Commission Charlotte Mecklenburg Planning Department 600 East Fourth Street Charlotte, North Carolina 28202 Prepared by: Mattson, Alexander and Associates, Inc. 2228 Winter Street Charlotte, North Carolina 28205 2 September 2015 Charlotte Comprehensive Architectural Survey, Phase II August 2015 I. Phase II Reconnaissance Survey Methodology In 2014, the City of Charlotte was awarded a federal grant from the North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office (HPO) to conduct a second reconnaissance-level architectural survey of Charlotte. The survey was conducted between January and August 2015. The earlier Phase I survey of 2013-2014 focused on the area within the radius of Route 4, a partial ring road around Charlotte’s central business district and surrounding neighborhoods. This Phase II survey concentrated on the areas within the current city limits that lie outside Route 4, much of which had been rural until the annexations and suburban development of recent decades. These outlying areas are currently documented in 361 HPO database records, seventeen of which are surveyed neighborhood or historic districts. The remaining records documented individual properties. In addition, this second study included an investigation of the Dilworth National Register Historic District, south of the center city, to determine the status of the individual resources within the district. Listed in the National Register in 1987 (locally designated 1983; 1992) the Dilworth Historic District has experienced intense development pressure in recent years. It is anticipated that these reconnaissance-level surveys (completed August 2014 and August 2015) will be the basis for three future intensive-level architectural investigations. -

Unlocking the Potential of Charlotte's Food System

UNLOCKING THE POTENTIAL OF CHARLOTTE’S FOOD SYSTEM AND FARMERS’ MARKETS July 2018 good food is good business PREPARED FOR The City of Charlotte BY 27 East 21st Street, 3rd Floor T: 212.260.1070 kkandp.com New York, NY 10010 F: 917.591.5104 PROJECT TEAM Founded as Karp Resources in 1990, Karen Karp & Partners (KK&P) is the nation’s Market Ventures, Inc. is an award-winning specialty urban planning and economic leading problem-solver for food-related enterprises, programs, and policies. Our development firm that assists public, non-profit, and for-profit clients with planning, personalized approach is designed to meet the unique challenges facing our clients. We creating, and managing innovative food-based projects and programs. We have apply a combination of analytic, strategic, and tactical approaches to every problem and particular expertise in public markets and farmers’ markets, where we blend cutting- deliver solutions that can be measured and are always meaningful. edge business practices with a thorough understanding of and appreciation for the unique challenges facing local farmers and small businesses. Our Good Food is Good Business division supports the healthy development, execution, and operations of food businesses and initiatives in the public and private sectors. Founded in 1996, Market Ventures stands apart from other firms because we are both Our services include strategic sourcing, feasibility analysis, market research, business experienced consultants and hands-on developers and operators. As consultants, we planning, project management, and evaluation. Our Good People are Good Business produce accurate, independent analyses and recommendations tailored to meet the division builds leadership and organizational effectiveness in the food sector through individual needs and circumstances of our clients. -

National Register of Historic Places Weekly Lists for 2004

National Register of Historic Places 2004 Weekly Lists January 2, 2004 ............................................................................................................................................. 3 January 9, 2004 ............................................................................................................................................. 5 January 16, 2004 ........................................................................................................................................... 8 January 23, 2004 ......................................................................................................................................... 10 January 30, 2004 ......................................................................................................................................... 14 February 6, 2004 ......................................................................................................................................... 19 February 13, 2004 ....................................................................................................................................... 23 February 20, 2004 ....................................................................................................................................... 25 February 27, 2004 ....................................................................................................................................... 29 March 5, 2004 ............................................................................................................................................ -

National Register of Historic Places Weekly Lists for 2014

National Register of Historic Places 2014 Weekly Lists National Register of Historic Places 2014 Weekly Lists ................................................................................ 1 January 3, 2014 ......................................................................................................................................... 3 January 10, 2014 ....................................................................................................................................... 9 January 17, 2014 ..................................................................................................................................... 16 January 24, 2014 ..................................................................................................................................... 24 January 31, 2014 ..................................................................................................................................... 29 February 7, 2014 ..................................................................................................................................... 34 February 14, 2014 ................................................................................................................................... 37 February 21, 2014 ................................................................................................................................... 43 February 28, 2014 ..................................................................................................................................