Approaches to Smile Design Mathematical to Artistic Interpretation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developmental Pattern of Human Milk Teeth

Int J Oral-Med Sci 9(2):75-87,2010 Original Article Developmental Pattern of Human Milk Teeth Kazuya Ohzeki,Rumi Ota-Yokota,and Hayato Ohshima Departments ofOral Diagnostics,and Histology,Cytology and Developmental Anatomy,Nihon University School of Dentistry at Matsudo,Matsudo,Chiba 271-8587,Japan Divisions of Anatomy and Cell Biology of the Hard Tissue,Niigata University Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences,Niigata,Niigata 951-8510,Japan Correspondence to: Kazuya Ohzeki The development of mammalian tooth cusps or ridges has been ex- E-mail: ohzeki.kazuya@ nihon-u.ac. plained by phylogenetic homology,such as the‘Tritubercular theory’ jp (Gregory 1934).However,descriptions of the incisor and canine are lacking, and many questions remain unanswered. In this paper, the authors examine crown development in human teeth in embryos and skulls of young children by micro computed tomography(μ-CT),and discuss these problems.The results were as follows: 1)In milk incisors and canines,the first swelling developed into the central marginal ridge,and new swellings became mesial and distal sites and also buccal and mesial sites. Mesial and distal promi- nences developed into mesial and distal mamelons,but labial and lingual swellings formed cingulums. 2)In upper first milk molars,the first swelling developed into a buccal cusp and new swellings around it became buccal and lingual,and also mesial and distal sites symmetrically.The lingual prominence formed a lingual cusp,and the mesial and distal prominences for- med mesial and distal cones or marginal ridges,but only the labial prominences developed into a mesio-buccal ridge. -

Biomechanics of Temporo-Mandibular Joint. Articilator. Movements of Mandible Protrusion Retrusion Lateral Excursion Opening-Closing

Biomechanics of temporo-mandibular joint. Articilator. Movements of mandible Protrusion Retrusion Lateral excursion Opening-Closing Opening-Closing Translatory movement of the mandibular condyle along the posterior wall of the articular eminence. Protrusion A protrusive movement occurs when the mandible moves forward. Retrusion Retraction of the mandible from any position Lateral excurcion When the mandible moves into a left lateral excurcion the right condyle moves forward and inward (Bennett angle), while the left condyle will shift slightly in a lateroposterior direction(Bennett movement). In this example, the left side is working side and the right side is nonworking side. When the mandible moves into a right lateral excurcion the left condyle moves forward and inward (Bennett angle), while the right condyle will shift slightly in a lateroposterior direction(Bennett movement). In this example, the right side is working side and the left side is nonworking side. Border movements of the mandible The most extreme positions to which the jaw is able to move. Laterally: max 10 mm Opening: 50-60 mm Protrusion: 9mm Retrusion:1 mm Described from sagittal, frontal and horizontal planes. Usually not affected by head or body posture. Mandibular movements Most mandibular movements occur around three dimensions. They include, the transverse(horizontal), vertical(frontal) and sagittal axes. Mandibular movements can be classified as border and intraborder movements. Border movements occuring in all three planes and intraborder movements are all possible movements of the mandible occur within the border envelope. Extreme movements in the sagittal plane The patient is instructed to move the mandible from centric relation(CR) to centric occlusion(CO), then edge to edge relationship(ER), then the maximum protrusive (MP) and then arc downward to the maximum opening position. -

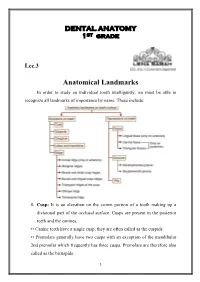

Anatomical Landmarks in Order to Study an Individual Tooth Intelligently, We Must Be Able to Recognize All Landmarks of Importance by Name

DENTAL ANATOMY 1ST grade Lec.3 Anatomical Landmarks In order to study an individual tooth intelligently, we must be able to recognize all landmarks of importance by name. These include: 1. Cusp: It is an elevation on the crown portion of a tooth making up a divisional part of the occlusal surface. Cusps are present in the posterior teeth and the canines. •• Canine teeth have a single cusp; they are often called as the cuspids. •• Premolars generally have two cusps with an exception of the mandibular 2nd premolar which frequently has three cusps. Premolars are therefore also called as the bicuspids. 1 •• Maxillary and mandibular 1st molars have five cusps, while other molars generally have four cusps. Each cusp is a gothic pyramid with four sides formed by four ridges that run down from the cusp tip: •• Mesial and distal cusp ridges (cusp slopes) •• Buccal/lingual cusp ridge •• Triangular ridge of the cusp. There are two cusp slopes on either side of the triangular ridge. In case of canines, there is a labial ridge analogous to the buccal ridge posterior teeth; there is a lingual ridge analogous to triangular ridge of posterior teeth. In the Table below the Number of cusps in different types of teeth: Tooth type Maxillary arch Mandibular arch Incisors 0 0 Canines 1 1 Premolars 2 2 in 1st premolar 3 or 2 in 2nd premolar Molars 1st molar 4 +1 accessory cusp 5 (cusp of Carabelli) 2nd molar 4 4 3rd molar 4 or 3 4 or 5 A cusp is named according to its location on the tooth. -

Dental Assisting Science I

ADED 110C: Dental Assisting Science I Hours: Lecture - 3, Lab - 0, Credits - 3 Prerequisite: none Term & Dates: Fall 2020 Faculty: Kelly O’Brien, CDA, RDH, MEd Faculty Accessibility: available via discussion board and email, virtual conferences by appointment Email: [email protected] DRAFT Course Outline – official syllabus will be available in August Course Description A study of the anatomy of the head, emphasizing the osteological landmarks and the structures of the oral cavity. Both the permanent and primary dentitions are studied, including embryonic development and eruption patterns. In addition, an introduction to the structure and function of the human body systems in health and disease will be presented. Return to Top Learning Outcomes Educated Person Statement of Philosophy Upon completion of this course, students will be able to: Pronounce, spell, and define key terminology required to function within the profession. Identify any tooth on the oral cavity by name, number, location, function and shorthand terms. Discuss the development of the head and neck from conception through adulthood with a focus on the oral cavity. Describe the major systems of the body, their functions, and relationship to oral health. Acquired Knowledge and Skills: List the classifications and function of each of the teeth. Identify the different tissues of the teeth and oral cavity. Identify the arrangement of the dentitions by arch, quadrant, and sextant. Label the surfaces of any tooth, and the divisions into thirds of the root and the crown. 1 Describe the dentitions using eruption and shedding dates. Provide the shorthand identification of each tooth using Palmer, FDI, and Universal. -

Noritake Super Porcelain EX-3

Porcelain for metal ceramic dental restorations Noritake Super Porcelain EX-3 Technical Instructions Contraindications: If the patient is hypersensitive to potassium-aluminosilicate glass or any other components, this product must not be used. Caution: 1. If the patient or the dental professional demonstrates a hypersensitivity reaction, such as rash, dermatitis, etc., discontinue use of the product and seek medical attention immediately. 2. When mixing materials or grinding a restoration being fabricated, use an approved dust mask and vacuum with air filter to protect your lungs from inhaling the dust. 3. When mixing materials or grinding a restoration being fabricated, use safety glasses to prevent the dust from getting into your eyes. If the dust gets into your eyes, immediately rinse with copious amounts of water and consult a physician. 4. Do not use for any purposes except for fabricating dental restorations. This product is for dental application only. 5. Do not touch the items heated by the furnace with your bare hands. 6. Paste Opaque, Paste Opaque Modifier, PASTE OPAQUE LIQUID, IS LIQUID, ES LIQUID and UP LIQUID are flammable. Do not use them near fire or high-temperature objects. 7. IS LIQUID is a stimulant liquid. When using it, have good ventilation and if necessary wear an approved dust mask, safety glasses and gloves. 8. Stain and plaque can accumulate on a restoration, once it has been put in position in the patient’s oral cavity, depending on the patient's eating habits or food choices. Instruct patients about the importance of cleaning their restorations. Precautions in use: 2 1. -

Surfaces and Ridges

Surfaces and ridges • The crowns of incisors and canines have four surfaces and ridge, while the crowns of premolars and molars have five surfaces The surfaces are: 1. Labial surface: is the surface which is toward the lip in incisors and canines (in anterior teeth). 2. Buccal surface: is the surface which is toward the cheek in premolars and molars (posterior teeth). The labial and buccal surfaces could be termed as the "facial surfaces". 3. Lingual surface: is the surface which is facing the tongue (all teeth). 4. Occlusal surface: is the surface of the posterior teeth coming in contact with the teeth in the opposite jaw during closing the mouth. In anterior teeth, this surface is called "incisal ridge". 5. Proximal surface: is the surface of the tooth facing toward adjacent teeth in the same dental arch. a. Mesial surface: is the surface which is facing toward the median line. b. Distal surface: is the surface which is facing away from the median line. All teeth have their mesial surfaces touching the distal surfaces of the adjacent tooth except the maxillary and mandibular central incisor (both permanent and deciduous).The area of the mesial and distal surface that touch its neighbor in the arch is called the "contact area". Division of the crown into thirds • For description, the crown and the root are divided into thirds according to the position of the surface. • Line angle: it is formed by the junction of two surfaces and gets its name from these surfaces. Example: mesio-labial line angle. • Point angle: it is formed by junction of three surfaces and get its name from these surfaces. -

Application of Root and Pulp Morphology Related to Endodontic

牙體形態學Dental morphology 學習目標 Application of Root and Pulp 能辨識及敘述牙齒之形態、特徵與功能意義,並能應用於臨 床診斷與治療 Morphology Related to 1. 牙齒形態相關名辭術語之定義與敘述 Endodontic Therapy 2. 牙齒號碼系統之介紹 3. 牙齒之顎間關係與生理功能形態之考慮 4. 恒齒形態之辨識與差異之比較 臺北醫學大學 牙醫學系 5. 乳齒形態之辨識與差異之比較 6. 恒齒與乳齒之比較 董德瑞老師 7. 牙髓腔形態 [email protected] 8. 牙齒之萌出、排列與咬合 9. 牙體形態學與各牙科臨床科目之相關 10.牙科人類學與演化發育之探討 參考資料 Summary The course of Dental Morphology provides the student with knowledge in the morphological characteristics of the teeth and 1. Woelfel, J.B. and Scheid, R.C: Dental Anatomy--Its Relevance to related oral structures upon which a functional concept of intra- Dentistry, ed. 6, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2002. arch relationships may be based for the clinical application to 2. Jordan, R.E. and Abrams, L.: Kraus' Dental Anatomy and patient assessment, diagnosis, treatment planning, and oral Occlusion, ed. 2, Mosby Year Book, St. Louis,1992. rehabilitation. 3. Ash, M.M.and Nelson, S.J.: Wheeler's Dental Anatomy, Physiology and Occlusion, ed. 8, W.B. Saunders Co., 2003. I. Internal pulp cavity morphology related to II. Location of root and cervical crown endodontic and restorative therapy concavities, furcations, depressions, and canals A. The shape of pulp cavities and configuration of, pulp canals A. Maxillary central incisors B. Shape of pulp cavities in sound young teeth B. Maxillary lateral incisors C Why pulp cavities get smaller in older teeth C. Mandibular central and lateral incisors D. Clinical application of pulp morphology related to restorative D. Maxillary canines dentistry E. Mandibular canines E. Clinical application of pulp morphology related to endodontics F. Maxillary first premolars G. Maxillary second premolars H. Mandibular first premolars I. -

PRT11-Xxxx-US

Inside Dental Technology November/December 2010, Volume 1, Issue 2 Published by AEGIS Communications MasterClass Implant-Retained Prosthetics Restoring the orally-handicapped with the All-on-4™ technique. by Irfan Atcha, DDS; and Luke Kahng, CDT People are living longer and demanding more functional solutions for missing dentition. Because many patients do not want to deal with the inconvenience of a conventional denture prosthetic, the demand for dental implant-retained prosthetics has increased. Any dental team that incorporates a less expensive, immediate-load product option can offer patients a great service. However, complete rehabilitation of the upper and lower jaw can be costly and time-consuming. The All-on-4 concept (Nobel Biocare, www.nobelbiocare.com) is an optimal alternative for many patients because it utilizes only four implants per arch for an immediate complete full fixed-detachable, screwretained prosthesis. The benefits are numerous and exciting for patients who have suffered with ill-fitting dentures. Dentulous patients in need of extractions with terminal dentition can take advantage of this concept, which increases stability, even with low bone volume. They can choose from several prosthetic options, such as a fixed, titanium implant bridge with acrylic veneering or individual crowns cemented to the bridgework. The treatment procedure uses tilting posterior implants to facilitate optimal support for an acrylic or composite bridge that can be fabricated and functioning just a few hours after surgery. Based on documented measurements, tilted implants have shown good clinical results. The system can be used in the maxilla, allowing the dentist to avoid sinus grafting, or in the mandible, to avoid having to place implants posterior to the symphysis.1 It also has higher patient acceptance rates because of its lower cost and shorter treatment time. -

FC Paste Stain General Precautions to Observe When Using This Product

Technical Instructions FC Paste Stain General precautions to observe when using this product 1.Cautions ① When polishing and grinding a restoration(“CERABIEN™ ZR”) being fabricated, use an approved dust mask and vacuum with an air filter to protect your lungs from inhaling either dust or liquid. ② A restoration made with “CERABIEN™ ZR” is very hot immediately after baking. Do not touch it with your bare hands for a considerable amount of time after removing it from the furnace. ③ After using "CERABIEN™ ZR" FC Paste Stain, wipe any remaining paste off the rim of the container and tighten the cap securely to prevent the contents from drying out. ④ “CERABIEN™ ZR” FC Paste Stain, IS LIQUID and ES LIQUID are flammable. Do not use them near fire or high-temperature objects. ⑤ IS LIQUID is a stimulant liquid. When using it, good ventilation and an approved dust mask, safety glasses and gloves are recommended. 2.Important notes ① When using “CERABIEN™ ZR”, if the patient or the dental professional demonstrates a hypersensitivity reaction, such as rash, dermatitis, etc., discontinue use of the product and seek medical attention immediately. ② When polishing and grinding a restoration(“CERABIEN™ ZR”) being fabricated, use safety glasses to prevent dust or liquid from getting into your eyes. If dust or liquid gets into your eyes, immediately rinse with copious amounts of water and seek medical attention. ③ Stains and plaque can accumulate on a restoration, once it has been put in position in the patient’s oral cavity, depending on the patient's eating habits or food choices. Instruct patients about the importance of cleaning their restorations. -

MD0501 4-1 LESSON ASSIGNMENT LESSON 4 Dental Anatomy

LESSON ASSIGNMENT LESSON 4 Dental Anatomy. LESSON ASSIGNMENT Paragraphs 4-1 through 4-25. LESSON OBJECTIVES After completing this lesson, you should be able to: 4-1. Identify the differences between groups of teeth. 4-2. Identify the number and characteristics of deciduous teeth. 4-3. Identify the permanent teeth according to the military numbering system. 4-4. Identify the terminology related to the surfaces of teeth. 4-5. Identify the division of teeth into thirds. 4-6. Identify basic anatomic terminology that describes the location, configuration, or shape of teeth. 4-7. Identify the correct description of the anatomy of each permanent maxillary tooth. 4-8. Identify the correct description of the anatomy of each permanent mandibular tooth. SUGGESTION After studying the assignment, complete the exercises at the end of this lesson. These exercises will help you to achieve the lesson objectives. MD0501 4-1 LESSON 4 DENTAL ANATOMY Section I. ASPECTS OF THE ANATOMIC DESCRIPTION OF TEETH 4-1. GENERAL Teeth are of different shapes and sizes. The primary function of teeth is to chew (masticate) food. They function in specialized ways in the preparation of food for digestion. There are two kinds of teeth--anterior and posterior. The anterior teeth are designed for the purpose of cutting and tearing food. The posterior teeth are designed for the purpose of grinding or crushing food. Teeth also have a role in speaking, by aiding in the production of sounds. Another function of teeth concerns appearance (esthetics). The presence or absence of teeth, their regularity or irregularity of position, and their color and condition greatly affect the appearance of the individual. -

1 – Introduction to Dental Anatomy

1 Introduction to Dental Anatomy LEARNING OBJECTIVES 5. Which of the following terms represents the surface of a tooth that is facing toward an adjoining tooth in the same dental arch? 1. Correctly define and pronounce the nomenclature (terms) A. Occlusal as emphasized in the bold type in this and each following B. Incisal chapter. C. Facial 2. Be able to identify each tooth of the primary and permanent D. Proximal dentitions using the Universal, Palmer, and Fédération Den- For additional study resources, please visit Expert Consult. taire Internationale (FDI) systems. 3. Correctly name and identify the surfaces, ridges, and ana- Dental anatomy is defined here as, but is not limited to, the study tomic landmarks of each tooth. of the development, morphology, function, and identity of each of 4. Understand and describe the methods used to measure ante- the teeth in the human dentitions, as well as the way in which the rior and posterior teeth. teeth relate in shape, form, structure, color, and function to the 5. Learn the tables of measurements and be able to discuss size other teeth in the same dental arch and to the teeth in the oppos- comparisons between the teeth from any viewing angle. A ing arch. Thus the study of dental anatomy, physiology, and occlu- useful skill at this point is to start illustrating the individual sion provides one of the basic components of the skills needed to teeth with line drawings. practice all phases of dentistry. The application of dental anatomy to clinical practice can be envisioned in Fig. 1.1A, where a faulty crown form has resulted in esthetic and periodontal problems that may be corrected by an appropriate restorative dental treatment, such as that illustrated in Fig. -

Oral Biology Practical Manual 2 ISBN

ORAL BIOLOGY PRACTICAL MANUAL 2 (Dental Anatomy/Morphology) Name: ………………………….……….………………………………..... Matric No: ..................................................................... Year: 20..….. ORAL BIOLOGY PRACTICAL MANUAL 2 (Dental Anatomy) (Purposely left blank) 2 ORAL BIOLOGY PRACTICAL MANUAL 2 (Dental Anatomy) ORAL BIOLOGY PRACTICAL MANUAL 2 (Dental Anatomy) Objectives The objectives of this manual are for students to: 1. Understand and describe the nomenclature of both the human primary and permanent dentitions. 2. Describe the structural and morphological similarities and differences of each tooth comprising the dentitions. 3. Draw the morphological features characteristic of each tooth of the human permanent dentition. The exercises in this manual must be completed periodically as to coincide with the relevant lectures and submit to the lecturer concern. The marks will contribute to the Oral Biology continuous assessment. Prepared by: Assoc Prof Col (R) Dr Basuri bin Faki July 2015 3 ORAL BIOLOGY PRACTICAL MANUAL 2 (Dental Anatomy) Table of Contents Ser Items Page 1 Dental Terminology 5 2 Maxillary Incisors 13 3 Mandibular Incisors 16 4 Maxillary and Mandibular Canines 20 5 Maxillary Premolars 23 6 Mandibular Premolars 26 7 Maxillary Molars 28 8 Mandibular Molars 31 9 Deciduous Dentition 34 10 Tooth Development and Age Identification 41 11 Tooth Variations / Anomalies 44 12 Dental Occlusion 47 4 ORAL BIOLOGY PRACTICAL MANUAL 2 (Dental Anatomy) 1. DENTAL TERMINOLOGY This part is concerned with the explanation and illustration of dental terminology. It deals with two groups of terms, the first relating to the anatomical and supporting structures of the tooth, and second consisting of terms of orientation. OBJECTIVES Upon completing this unit, you should be able to: a.