1 – Introduction to Dental Anatomy

Total Page:16

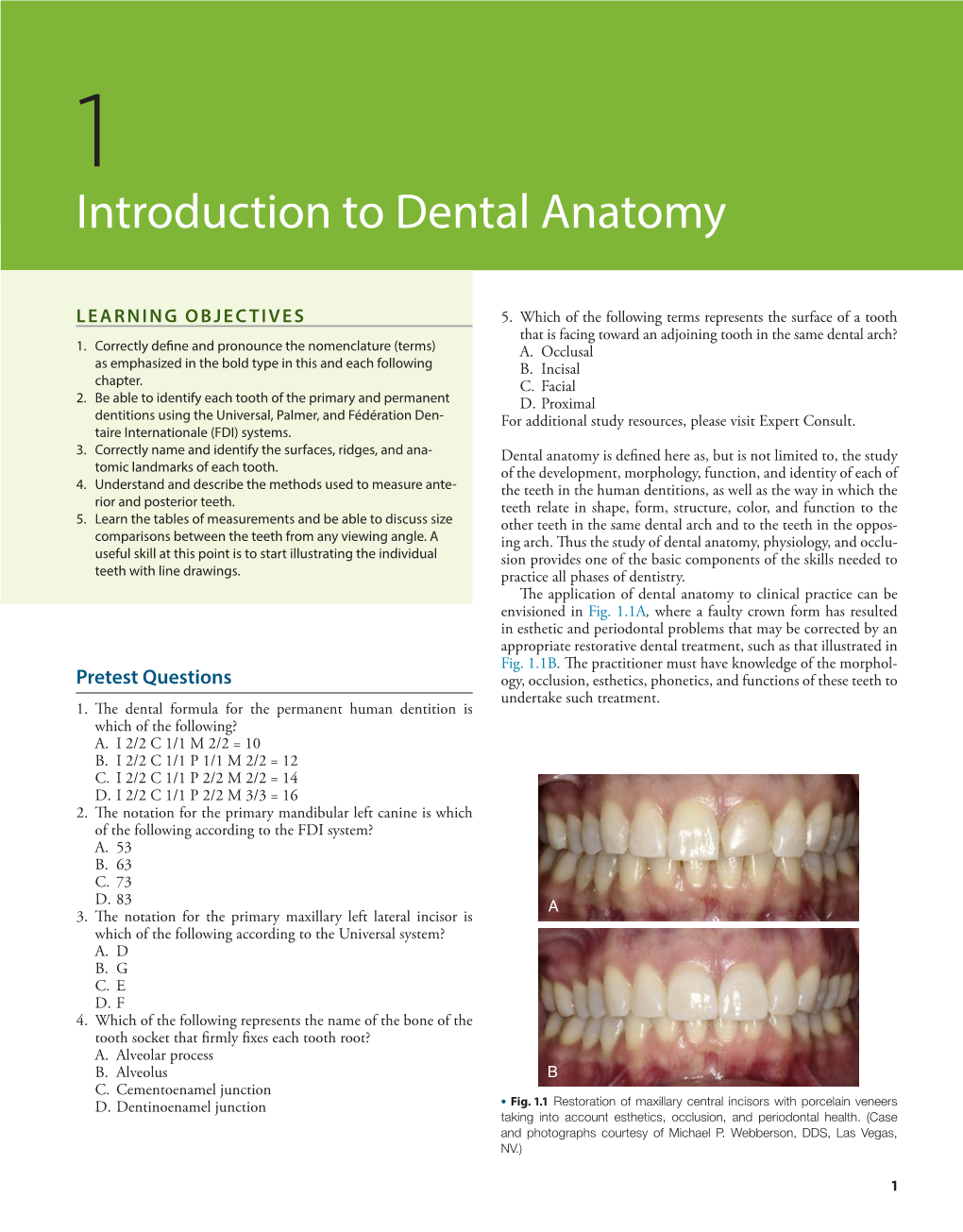

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homologies of the Anterior Teeth in Lndriidae and a Functional Basis for Dental Reduction in Primates

Homologies of the Anterior Teeth in lndriidae and a Functional Basis for Dental Reduction in Primates PHILIP D. GINGERICH Museum of Paleontology, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 KEY WORDS Dental reduction a Lemuriform primates . Indriidae . Dental homologies - Dental scraper . Deciduous dentition - Avahi ABSTRACT In a recent paper Schwartz ('74) proposes revised homologies of the deciduous and permanent teeth in living lemuriform primates of the family Indriidae. However, new evidence provided by the deciduous dentition of Avahi suggests that the traditional interpretations are correct, specifically: (1) the lat- eral teeth in the dental scraper of Indriidae are homologous with the incisors of Lemuridae and Lorisidae, not the canines; (2) the dental formula for the lower deciduous teeth of indriids is 2.1.3; (3) the dental formula for the lower perma- nent teeth of indriids is 2.0.2.3;and (4)decrease in number of incisors during pri- mate evolution was usually in the sequence 13, then 12, then 11. It appears that dental reduction during primate evolution occurred at the ends of integrated in- cisor and cheek tooth units to minimize disruption of their functional integrity. Anterior dental reduction in the primate Schwartz ('74) recently reviewed the prob- family Indriidae illustrates a more general lem of tooth homologies in the dental scraper problem of direction of tooth loss in primate of Indriidae and concluded that no real evi- evolution. All living lemuroid and lorisoid pri- dence has ever been presented to support the mates (except the highly specialized Dauben- interpretation that indriids possess four lower tonid share a distinctive procumbent, comb- incisors and no canines. -

Deciduous Teeth Overview

Deciduous Teeth Overview: ● Deciduous teeth are the first set of teeth a person has. They are a total of 20. ● It is important to learn about the teething stage to help make it a less painful and irritating experience for children. ● Most common problems for deciduous teeth: Caries (cavities), pain and infection, thumb sucking and using a pacifier for longer than the average age. ● A child’s face and teeth may also be injured, affecting the permanent tooth that would replace the injured primary tooth. ● Care guidelines for children’s teeth and mouths should be followed and taken seriously. What are primary teeth? They are the first set of teeth a person has and they remain until it is time for them to fall and be replaced by permanent teeth. Number: 20 teeth Other names: Baby teeth, shed teeth, temporary teeth, primary teeth, milk teeth. Importance of deciduous teeth: ● They help the child chew food. ● They aid speed and enunciation. ● Primary teeth occupy a place in the mouth so they can later allow permanent teeth to appear in their correct place. When a child loses a primary tooth prematurely, this may affect the shape and order of the permanent teeth. ● They help with a child’s aesthetic and increase confidence while smiling When do deciduous teeth appear and when do they shed? Deciduous teeth start appearing gradually starting the age of 6-7 months, beginning with the lower jaw. They are fully developed at the age of 2.5. Development of deciduous teeth (teething): Teething is when a child starts to develop his/her first teeth. -

Intrusion of Incisors to Facilitate Restoration: the Impact on the Periodontium

Note: This is a sample Eoster. Your EPoster does not need to use the same format style. For example your title slide does not need to have the title of your EPoster in a box surrounded with a pink border. Intrusion of Incisors to Facilitate Restoration: The Impact on the Periodontium Names of Investigators Date Background and Purpose This 60 year old male had severe attrition of his maxillary and mandibular incisors due to a protrusive bruxing habit. The patient’s restorative dentist could not restore the mandibular incisors without significant crown lengthening. However, with orthodontic intrusion of the incisors, the restorative dentist was able to restore these teeth without further incisal edge reduction, crown lengthening, or endodontic treatment. When teeth are intruded in adults, what is the impact on the periodontium? The purpose of this study was to determine the effect of adult incisor intrusion on the alveolar bone level and on root length. Materials and Methods We collected the orthodontic records of 43 consecutively treated adult patients (aged > 19 years) from four orthodontic practices. This project was approved by the IRB at our university. Records were selected based upon the following criteria: • incisor intrusion attempted to create interocclusal space for restorative treatment or correction of excessive anterior overbite • pre- and posttreatment periapical and cephalometric radiographs were available • no incisor extraction or restorative procedures affecting the cementoenamel junction during the treatment period pretreatment pretreatment Materials and Methods We used cephalometric and periapical radiographs to measure incisor intrusion. The radiographs were imported and the digital images were analyzed with Image J, a public-domain Java image processing program developed at the US National Institutes of Health. -

External Root Resorption of Young Premolar Teeth in Dentition With

10.5005/jp-journals-10015-1236 KapilaORIGINAL Arambawatta RESEARCH et al External Root Resorption of Young Premolar Teeth in Dentition with Crowding Kapila Arambawatta, Roshan Peiris, Dhammika Ihalagedara, Anushka Abeysundara, Deepthi Nanayakkara ABSTRACT least understood type of root resorption, characterized by its The present study was conducted to investigate the prevalence FHUYLFDOORFDWLRQDQGLQYDVLYHQDWXUH7KLVUHVRUSWLYHSURFHVV of external cervical resorption (ECR) in different tooth surfaces which leads to prRJUHVVLYHDQGXVXDOO\GHVWUXFWLYHORVVRI RIPD[LOODU\¿UVWSUHPRODUVLQD6UL/DQNDQSRSXODWLRQ tooth structure has been a source of interest to clinicians A sample of 59 (15 males, 44 females) permanent maxillary 2-5 ¿UVWSUHPRODUV DJHUDQJH\HDUV ZHUHXVHG7KHWHHWK DQGUHVHDUFKHUVIRURYHUDFHQWXU\ 7KHH[DFWFDXVHRI had been extracted for orthodontic reasons and were stored (&5LVSRRUO\XQGHUVWRRG$OWKRXJKWKHHWLRORJ\DQG LQIRUPDOLQ0RUSKRORJLFDOO\VRXQGWHHWKZHUHVHOHFWHG SDWKRJHQHVLVUHPDLQREVFXUHVHYHUDOSRWHQWLDOSUHGLVSRVLQJ IRUWKHVWXG\7KHWHHWKZHUHVWDLQHGZLWKFDUEROIXFKVLQ7KH IDFWRUVKDYHEHHQSXWIRUZDUGDQGRIWKHVHWKHLQWUDFRURQDO cervical regions of the stained teeth were observed under 10× 6 PDJQL¿FDWLRQV XVLQJ D GLVVHFWLQJ PLFURVFRSH 2O\PSXV 6= bleaching has been the most widely documented factor. In WRLGHQWLI\DQ\UHVRUSWLRQDUHDV7KHUHVRUSWLRQDUHDVSUHVHQW addition, dental trauma, orthodontic treatment, periodontal on buccal, lingual, mesial and distal aspects of all teeth were WUHDWPHQWVXUJHU\LQYROYLQJWKHFHPHQWRHQDPHOMXQFWLRQ UHFRUGHG DQGLGLRSDWKLFHWLRORJ\KDYHDOVREHHQGHVFULEHG2,7-11 -

The Catenary Curve: a Guide to Gary Goldstein1, Yash Kapadia2, Mandibular Arch Form Terry Y Lin1 and Paul Zhivago1

Short Communication iMedPub Journals Periodontics and Prosthodontics: Open Access 2015 http://www.imedpub.com/ ISSN 2471-3082 Vol. 1 No. 1:1 DOI: 10.21767/2471-3082.100001 The Catenary Curve: A Guide to Gary Goldstein1, Yash Kapadia2, Mandibular Arch Form Terry Y Lin1 and Paul Zhivago1 1 Department of Prosthodontics, New Abstract York University College of Dentistry, New This article revisits a pre-existing geometric concept, the catenary curve, redefines York, USA its dental application and proposes it as a useful aid in visualizing the mandibular 2 Former Resident Advanced Education dental arch form both clinically and in CADCAM design. Program in Prosthodontics, New York University College of Dentistry, New Keywords: Catenary curve; Parabolic curve; CAD-CAM; Artificial tooth placement; York, USA Mandibular arch form Gary Goldstein Received: November 09, 2015; Accepted: November 17, 2015; Published: November Corresponding author: 20, 2015 [email protected] Department of Prosthodontics, New York Introduction University College of Dentistry, 308 Second Ave, NY 10010, New York, USA. The Miriam Webster online dictionary describes the catenary curve as: “the curve assumed by a cord of uniform density and cross-section that is perfectly flexible but not capable of being Citation: Goldstein G (2015) The Catenary stretched and that hangs freely from two fixed points”. It was first Curve: A Guide to Mandibular Arch Form. described by MacConaill and Scher [1], who suggested that normal Periodon Prosthodon 1: 1. human dental arches conform closely to a catenary curve. Scott [2], in a paper using a catenometer on dried skulls, concluded that the lower border of the mandible more closely follows a catenary parabola as: “a plane curve generated by a point moving so that curve rather than the dental arches. -

Lower Lip Numbness Due to Peri-Radicular Dental Infection

Lower Lip Numbness Due to Peri~Radicular Dental Infection WC Ngeow, FFDRCS, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Faculty of Dentistry, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), Jalan Raja Muda Abdul Aziz, 50300 Kuala Lumpur lip numbness. She complained of a toothache on her lower left first premolar and had seen her dentist who Loss of sensation in the lower lip is a common symptom. performed emergency root canal treatment. Following Frequently, it can be ascribed to surgical procedures that, she felt numbness of her lower lip. carried our in the region of the inferior alveolar nerve or its mental branch. In addition, trauma, haematoma or Clinical examination revealed a mandibular left first acute infections may cause the problem 1. Localised and premolar with a dressing. The tooth was slightly tender metastatic neoplasms, systemic disorders and some to percussion. Other neighbouring teeth reacted nor drugs are the other causes responsible 1. mally to percussion. No swelling could be seen at the buccal sulcus of the premolar. Her lower left lip looked Although benign in appearance, mental nerve normal, but she could not distinguish sharp pain when neuropathy is frequently of significance. Most often it pricked with a dental probe. is associated with malignant diseases. Breast cancer is the most common cause '. Other common causes Radiographic examination revealed a radiolucency at the include malignant blood diseases 2 which may include peri-radicular area of the mandibular left first premolar Burkitt's lymphoma, Hodgkins lymphoma and and another radiolucency just slightly away from the multiple myeloma. peri-radicular area of the mandibular left canine tooth. -

Micro-CT Evaluation of Root and Canal Morphology of Mandibular First Premolars with Radicular Grooves

Brazilian Dental Journal (2017) 28(5): 597-603 ISSN 0103-6440 http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0103-6440201601784 1Department of Restorative Dentistry, Micro-CT Evaluation of Root and School of Dentistry of Ribeirao Preto, USP – Universidade de São Canal Morphology of Mandibular First Paulo, Ribeirao Preto, SP, Brazil 2Department of Endodontics, Premolars with Radicular Grooves School of Dentistry, UNAERP - Universidade de Ribeirão Preto, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil Correspondence: Manoel Damião de Sousa-Neto, Rua Célia de Oliveira 1 2 Emanuele Boschetti , Yara Terezinha Correa Silva-Sousa , Jardel Francisco Meirelles 350, 14024-070, Ribeirão Mazzi-Chaves1, Graziela Bianchi Leoni2, Marco Aurélio Versiani1, Jesus Djalma Preto, SP, Brasil. Tel: +55-16-9991- Pécora1, Paulo Cesar Saquy1, Manoel Damião de Sousa-Neto1 2696. e-mail: [email protected] The aim of this study was to evaluate morphological features of 70 single-rooted mandibular first premolars with radicular grooves (RG) using micro-CT technology. Teeth were scanned and evaluated regarding the morphology of the roots and root canals as well as length, depth and percentage frequency location of the RG. Volume, surface area and Structure Model Index (SMI) of the canals were measured for the full root length. Two-dimensional parameters and frequency of canal orifices were evaluated at 1, 2, and 3 mm levels from the apical foramen. The number of accessory canals, the dentinal thickness, and cross-sectional appearance of the canal at different root levels were also recorded. Expression of deep grooves was observed in 21.42% of the sample. Mean lengths of root and RG were 13.43 mm and 8.5 mm, respectively, while depth of the RG ranged from 0.75 to 1.13 mm. -

Dental Anatomy

Dental Anatomy: 101 bcbsfepdental.com Learn more about your teeth! What Makes a Tooth? Check out the definitions of the anatomical terms depicted in the diagram to the right. Enamel - Dental enamel is the hard thin translucent layer that serves as protection for the dentin of a tooth. It is made up of calcium salts. It is the hardest substance in the body. Dentin - Dentin is the hard, dense, calcareous (made up of calcium carbonate) material that makes up the majority of the tooth underneath the enamel. It is harder and denser than bone. It is one of four components that make up the tooth. It is the second layer of the tooth. Anatomical Crown - The natural, top part of a tooth, which is covered in enamel and is the part that you can see extending above the gum line. Pulp Chamber – The area within the natural crown of the tooth where the tooth pulp resides. Gingiva – also known as gums – the soft tissues that cover part of the tooth and bone. Gingiva helps protect the teeth The Anatomy of a Tooth from any infection or damage from food and everyday Your teeth are composed of hard (calcified) and soft (non-calcified) interactions with the outer world. dental tissues. Enamel, dentin and Neck - The area of the tooth where the crown joins the root. cementum are hard tissues. Pulp, or the center of the tooth that contains Root Canal – Not to be confused with Root Canal nerves, blood vessels and connective Treatment, the root canal is a space inside your tooth root tissue—is a soft tissue. -

Clinical Significance of Dental Anatomy, Histology, Physiology, and Occlusion

1 Clinical Significance of Dental Anatomy, Histology, Physiology, and Occlusion LEE W. BOUSHELL, JOHN R. STURDEVANT thorough understanding of the histology, physiology, and Incisors are essential for proper esthetics of the smile, facial soft occlusal interactions of the dentition and supporting tissues tissue contours (e.g., lip support), and speech (phonetics). is essential for the restorative dentist. Knowledge of the structuresA of teeth (enamel, dentin, cementum, and pulp) and Canines their relationships to each other and to the supporting structures Canines possess the longest roots of all teeth and are located at is necessary, especially when treating dental caries. The protective the corners of the dental arches. They function in the seizing, function of the tooth form is revealed by its impact on masticatory piercing, tearing, and cutting of food. From a proximal view, the muscle activity, the supporting tissues (osseous and mucosal), and crown also has a triangular shape, with a thick incisal ridge. The the pulp. Proper tooth form contributes to healthy supporting anatomic form of the crown and the length of the root make tissues. The contour and contact relationships of teeth with adjacent canine teeth strong, stable abutments for fixed or removable and opposing teeth are major determinants of muscle function in prostheses. Canines not only serve as important guides in occlusion, mastication, esthetics, speech, and protection. The relationships because of their anchorage and position in the dental arches, but of form to function are especially noteworthy when considering also play a crucial role (along with the incisors) in the esthetics of the shape of the dental arch, proximal contacts, occlusal contacts, the smile and lip support. -

Oral Structure, Dental Anatomy, Eruption, Periodontium and Oral

Oral Structures and Types of teeth By: Ms. Zain Malkawi, MSDH Introduction • Oral structures are essential in reflecting local and systemic health • Oral anatomy: a fundamental of dental sciences on which the oral health care provider is based. • Oral anatomy used to assess the relationship of teeth, both within and between the arches The color and morphology of the structures may vary with genetic patterns and age. One Quadrant at the Dental Arches Parts of a Tooth • Crown • Root Parts of a Tooth • Crown: part of the tooth covered by enamel, portion of the tooth visible in the oral cavity. • Root: part of the tooth which covered by cementum. • Posterior teeth • Anterior teeth Root • Apex: rounded end of the root • Periapex (periapical): area around the apex of a tooth • Foramen: opening at the apex through which blood vessels and nerves enters • Furcation: area of a two or three rooted tooth where the root divides Tooth Layers • Enamel: the hardest calcified tissue covering the dentine in the crown of the tooth (96%) mineralized. • Dentine: hard calcified tissue surrounding the pulp and underlying the enamel and cementum. Makes up the bulk of the tooth, (70%) mineralized. Tooth Layers • Pulp: the innermost noncalsified tissues containing blood vessels, lymphatics and nerves • Cementum: bone like calcified tissue covering the dentin in the root of the tooth, 50% mineralized. Tooth Layers Tooth Surfaces • Facial: Labial , Buccal • Lingual: called palatal for upper arch. • Proximal: mesial , distal • Contact area: area where that touches the adjacent tooth in the same arch. Tooth Surfaces • Incisal: surface of an incisor which toward the opposite arch, the biting surface, the newly erupted “permanent incisors have mamelons”: projections of enamel on this surface. -

Anterior Esthetic Crown-Lengthening Surgery: a Case Report

C LINICAL P RACTICE Anterior Esthetic Crown-Lengthening Surgery: A Case Report • Jim Yuan Lai, BSc, DMD, MSc (Perio) • • Livia Silvestri, BSc, DDS, MSc (Perio) • • Bruno Girard, DMD, MSc (Perio) • Abstract The theoretical concepts underlying crown-lengthening surgery are reviewed, and a patient who underwent esthetic crown-lengthening surgery is described. An overview of the various indications and contraindications is presented. MeSH Key Words: case report; crown lengthening; periodontium/surgery © J Can Dent Assoc 2001; 67(10):600-3 This article has been peer reviewed. he appearance of the gingival tissues surrounding room for adequate crown preparation and reattachment of the teeth plays an important role in the esthetics of the epithelium and connective tissue.4 Furthermore, by T the anterior maxillary region of the mouth. altering the incisogingival length and mesiodistal width of Abnormalities in symmetry and contour can significantly the periodontal tissues in the anterior maxillary region, the affect the harmonious appearance of the natural or pros- crown-lengthening procedure can build a harmonious thetic dentition. As well nowadays, patients have a greater appearance and improve the symmetry of the tissues. desire for more esthetic results which may influence treat- Good communication between the restoring dentist and ment choice. the periodontist is important to achieve optimal results An ideal anterior appearance necessitates healthy and with crown-lengthening surgery, particularly in esthetically inflammation-free periodontal tissues. Garguilo1 described demanding cases. In addition to establishing the smile line, various components of the periodontium, giving mean the restoring dentist evaluates the anterior and posterior dimensions of 1.07 mm for the connective tissue, 0.97 mm occlusal planes for harmony and balance, as well as the for the epithelial attachment and 0.69 mm for the sulcus anterior and posterior gingival contours. -

Human Anatomy and Physiology

LECTURE NOTES For Nursing Students Human Anatomy and Physiology Nega Assefa Alemaya University Yosief Tsige Jimma University In collaboration with the Ethiopia Public Health Training Initiative, The Carter Center, the Ethiopia Ministry of Health, and the Ethiopia Ministry of Education 2003 Funded under USAID Cooperative Agreement No. 663-A-00-00-0358-00. Produced in collaboration with the Ethiopia Public Health Training Initiative, The Carter Center, the Ethiopia Ministry of Health, and the Ethiopia Ministry of Education. Important Guidelines for Printing and Photocopying Limited permission is granted free of charge to print or photocopy all pages of this publication for educational, not-for-profit use by health care workers, students or faculty. All copies must retain all author credits and copyright notices included in the original document. Under no circumstances is it permissible to sell or distribute on a commercial basis, or to claim authorship of, copies of material reproduced from this publication. ©2003 by Nega Assefa and Yosief Tsige All rights reserved. Except as expressly provided above, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission of the author or authors. This material is intended for educational use only by practicing health care workers or students and faculty in a health care field. Human Anatomy and Physiology Preface There is a shortage in Ethiopia of teaching / learning material in the area of anatomy and physicalogy for nurses. The Carter Center EPHTI appreciating the problem and promoted the development of this lecture note that could help both the teachers and students.