The Oregon Constitutional Law Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Limited Horizons on the Oregon Frontier : East Tualatin Plains and the Town of Hillsboro, Washington County, 1840-1890

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1988 Limited horizons on the Oregon frontier : East Tualatin Plains and the town of Hillsboro, Washington County, 1840-1890 Richard P. Matthews Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Matthews, Richard P., "Limited horizons on the Oregon frontier : East Tualatin Plains and the town of Hillsboro, Washington County, 1840-1890" (1988). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3808. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5692 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Richard P. Matthews for the Master of Arts in History presented 4 November, 1988. Title: Limited Horizons on the Oregon Frontier: East Tualatin Plains and the Town of Hillsboro, Washington county, 1840 - 1890. APPROVED BY MEMBE~~~ THESIS COMMITTEE: David Johns n, ~on B. Dodds Michael Reardon Daniel O'Toole The evolution of the small towns that originated in Oregon's settlement communities remains undocumented in the literature of the state's history for the most part. Those .::: accounts that do exist are often amateurish, and fail to establish the social and economic links between Oregon's frontier towns to the agricultural communities in which they appeared. The purpose of the thesis is to investigate an early settlement community and the small town that grew up in its midst in order to better understand the ideological relationship between farmers and townsmen that helped shape Oregon's small towns. -

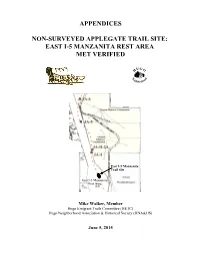

Appendices Non-Surveyed Applegate Trail Site: East I

APPENDICES NON-SURVEYED APPLEGATE TRAIL SITE: EAST I-5 MANZANITA REST AREA MET VERIFIED Mike Walker, Member Hugo Emigrant Trails Committee (HETC) Hugo Neighborhood Association & Historical Society (HNA&HS) June 5, 2015 NON-SURVEYED APPLEGATE TRAIL SITE: EAST I-5 MANZANITA REST AREA MET VERIFIED APPENDICES Appendix A. Hugo Neighborhood Association & Historical Society (HuNAHS) Standards for All Emigrant Trail Inventories and Decisions Appendix B. HuNAHS’ Policy for Document Verification & Reliability of Evidence Appendix C. HETC’s Standards: Emigrant Trail Inventories and Decisions Appendix D1. Pedestrian Survey of Stockpile Site South of Chancellor Quarry in the I-5 Jumpoff Joe-Glendale Project, Josephine County (separate web page) Appendix D2. Subsurface Reconnaissance of the I-5 Chancellor Quarry Stockpile Project, and Metal Detector Survey Within the George and Mary Harris 1854 - 55 DLC (separate web page) Appendix D3. May 18, 2011 Email/Letter to James Black, Planner, Josephine County Planning Department (separate web page) Appendix D4. The Rogue Indian War and the Harris Homestead Appendix D5. Future Studies Appendix E. General Principles Governing Trail Location & Verification Appendix F. Cardinal Rules of Trail Verification Appendix G. Ranking the Reliability of Evidence Used to Verify Trial Location Appendix H. Emigrant Trail Classification Categories Appendix I. GLO Surveyors Lake & Hyde Appendix J. Preservation Training: Official OCTA Training Briefings Appendix K. Using General Land Office Notes And Maps To Relocate Trail Related Features Appendix L1. Oregon Donation Land Act Appendix L2. Donation Land Claim Act Appendix M1. Oregon Land Survey, 1851-1855 Appendix M2. How Accurate Were the GLO Surveys? Appendix M3. Summary of Objects and Data Required to Be Noted In A GLO Survey Appendix M4. -

“We'll All Start Even”

Gary Halvorson, Oregon State Archives Gary Halvorson, Oregon State “We’ll All Start Even” White Egalitarianism and the Oregon Donation Land Claim Act KENNETH R. COLEMAN THIS MURAL, located in the northwest corner of the Oregon State Capitol rotunda, depicts John In Oregon, as in other parts of the world, theories of White superiority did not McLoughlin (center) of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) welcoming Presbyterian missionaries guarantee that Whites would reign at the top of a racially satisfied world order. Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding to Fort Vancouver in 1836. Early Oregon land bills were That objective could only be achieved when those theories were married to a partly intended to reduce the HBC’s influence in the region. machinery of implementation. In America during the nineteenth century, the key to that eventuality was a social-political system that tied economic and political power to land ownership. Both the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 and the 1857 Oregon Constitution provision barring Blacks from owning real Racist structures became ingrained in the resettlement of Oregon, estate guaranteed that Whites would enjoy a government-granted advantage culminating in the U.S. Congress’s passing of the DCLA.2 Oregon’s settler over non-Whites in the pursuit of wealth, power, and privilege in the pioneer colonists repeatedly invoked a Jacksonian vision of egalitarianism rooted in generation and each generation that followed. White supremacy to justify their actions, including entering a region where Euro-Americans were the minority and — without U.S. sanction — creating a government that reserved citizenship for White males.3 They used that govern- IN 1843, many of the Anglo-American farm families who immigrated to ment not only to validate and protect their own land claims, but also to ban the Oregon Country were animated by hopes of generous federal land the immigration of anyone of African ancestry. -

Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882 Jerry Rushford Pepperdine University

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Churches of Christ Heritage Center Jerry Rushford Center 1-1-1998 Christians on the Oregon Trail: Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882 Jerry Rushford Pepperdine University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/heritage_center Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Rushford, Jerry, "Christians on the Oregon Trail: Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882" (1998). Churches of Christ Heritage Center. Item 5. http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/heritage_center/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Jerry Rushford Center at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Churches of Christ Heritage Center by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHRISTIANS About the Author ON THE Jerry Rushford came to Malibu in April 1978 as the pulpit minister for the University OREGON TRAIL Church of Christ and as a professor of church history in Pepperdine’s Religion Division. In the fall of 1982, he assumed his current posi The Restoration Movement originated on tion as director of Church Relations for the American frontier in a period of religious Pepperdine University. He continues to teach half time at the University, focusing on church enthusiasm and ferment at the beginning of history and the ministry of preaching, as well the nineteenth century. The first leaders of the as required religion courses. movement deplored the numerous divisions in He received his education from Michigan the church and urged the unity of all Christian College, A.A. -

THE SIGNERS of the OREGON MEMORIAL of 1838 the Present Year, 1933, Is One of Unrest and Anxiety

THE SIGNERS OF THE OREGON MEMORIAL OF 1838 The present year, 1933, is one of unrest and anxiety. But a period of economic crisis is not a new experience in the history of our nation. The year 1837 marked the beginning of a real panic which, with its after-effects lasted well into 1844. This panic of 1837 created a restless population. Small wonder, then, that an appeal for an American Oregon from a handful of American settlers in a little log mission-house, on the banks of the distant Willamette River, should have cast its spell over the depression-striken residents of the Middle Western and Eastern sections of the United States. The Memorial itself, the events which led to its inception, and the detailed story o~ how it was carried across a vast contin ent by the pioneer Methodist missioinary, Jason Lee, have already been published by the present writer.* An article entitled The Oregon Memorial of 1838" in the Oregon Historical Quarterly for March, 1933, also by the writer, constitutes the first docu mented study of the Memorial. Present-day citizens of the "New Oregon" will continue to have an abiding interest in the life stories of the rugged men who signed this historiq first settlers' petition in the gray dawn of Old Oregon's history. The following article represents the first attempt to present formal biographical sketches of the thirty-six signers of this pioneer document. The signers of the Oregon Memorial of 1838 belonged to three distinct groups who resided in the Upper Willamette Valley and whose American headquarters were the Methodist Mission house. -

ORGANIZERS of the FIRST GOVERNMENT in OREGON [George H

ORGANIZERS OF THE FIRST GOVERNMENT IN OREGON [George H. Himes, Assistant Secretary and Curator of the Oregon Historical Society, has for many years worked earnestly on the task of preparing the statistics of those who participated in the famous meeting at Champoeg on May 2, 1843, when the Provisional Government of Oregon was organized. At that time Oregon embraced all of Washington, Idaho, parts of Montana, Wyoming and British Columbia, as well as the area that has retained the old name. The Champoeg meeting is, therefore, im portant to the history of the entire Northwest. Mr. Himes has compiled a beautiful souvernir of the seventy-second anniversary of the meeting and its fifteenth annual celebration at Old Champoeg, thirty-three miles south of Portland, on Saturday, May I, 1915. From Mr. Himes's souvernir the following is reproduced that readers of this Quarterly may possess the valuable record.-Editor.] Champoeg was the site of the first Hudson's Bay Company's ware house on the Willamette River, south of Oregon City, and the shipping point of the first wheat in that valley, beginning about 1830. The ease with which it could be reached by land or water by the settlers was the cause of its being chosen as the place of meeting on May 2, 1843. Following is the official record of the meeting held at what they called Champc;>oick, May 2, 1843 : At a public meeting of the inhabitants of the Willamette settlements, held in accordance with the call of the committee chosen at a former meeting, for the purpose of taking steps to organize themselves into a civil community, and provide themselves with the protection secured by the enforcement of law and order, Dr. -

Tii1ztpm in the Pacific Northwest in the Pacific K Story of Missionary Days K Story of a -- T5o $T.R Arg-Nf-Tt- Aeaict in Memory of Lissette ' ?Eter

Tii1ztpM Its Rise fliTLd Fall k story of Missionary days in the Pacific Northwest 1836 184T Miles Cannors A -- T5o $t.r arg-nf-tt- aeaict in memory of Lissette_' ?eter a ThL /7i55/on'' /847 WAI1LATPU ITS RISE AND FALL 1836-1847 A STORY OF PIONEER DAYS IN THEPACIFIC NORTHWEST BASED ENTIRELY UPON HISTORICAL RESEARCH By MILES CANNON FEATURING T H B JOURNEY 0 F NARCISSA PRENTISS WHITMAN, THE FIRST AMERICAN WOMAN TO CROSS THE CONTINENT AND LOOK UPON THE COLUMBIA RIVER-HER BEAUTIFUL CHARACTER-INCIDENTS OF THE TRAIL-HER MISSIONARY LIFE WITH THE CAYUSE INDIANS -HER DREADFUL MASSACRE TOGETHER WITH HER HUSBAND AND TWELVE OTHERS-THE TAKING INTO CAPTIVITY OF TWO SCORE WOMEN AND GIRLS, AND THE TREATMENT ACCORDED THEM BY THE SAVAGE INDIANS- THE FINAL RESCUE, ETC. 'TEUS WE ARE PUT IN TRAINING FOR A. LOVE WHICH KNOWS NO SEX. NOR PERSON. NOR PARTIALITY, BUT WHICHSEEKETH VIRTUE AND WISDOM EVERYWHERE, TO THE END OF INCREAS- ING VIRTUE AND WISDOM" 1915 CAPITAL NEws JoB ROOMS BoISE. IDAHo TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I Page I NARCISSA PRENTISS-THE AMERICAN BOARD-LIBERTY LANDING-REV. SAMUEL PARKER-JYR. MARCUS WHITMAN. Chapter II Page 5 A STUDY OF DR. WHITMAN-THE MARRIAGE-HENRY H. SPAIJLDING-A PEACE CON1RENCE-WM. H. GRAY-MRS. SPAULDING. Chapter III Page S A STUDY OF HENRY H, SPAULDING-THE RECONCILIA- TION-DESCRIPTION OF MRS. SPAULDING. Chapter IV Page 11 THE START-ARRIVAL AT ST. LOUIS-TWILIGHT ON THE MISSOURI-THE AMERICAN FUR COMPANY-OTOR AGENCY - FORT LARAMIE - BELLEVUE - FORT HALL - PA'WNEE VILLAGE. Chapter V Page 17 ON THE OREGON TRAIL-THE GREEN RIVER RENDEZ- VOUS-INCIDENTS OF THE JOURNEY-GRAY'S IMPRES- SIONS-JULY 4TH, ON THE SUMMIT-THE LAMENT. -

Subdivisions of the Original Lewis County

SUBDIVISIONS OF THE ORIGINAL LEWIS COUNTY The people of the provisional government of Oregon claimed all the land in Old Oregon which extended from the Pacific Coast to the Rocky Mountains and from the forty-second parallel to fifty four forty. At a meeting held at Champoeg on July 5, 1843, the people adopted a law dividing Oregon into four districts, two of which embraced all of the future State of Washington. Twality District took in all of the land west of the Willamette River and a sup posed line running north and south from that river and lying be tween fifty-four forty on the north and the Yamhill River on the south. Clackamas District embraced all the land east of that Wil lamette line to the Rocky Mountains, north of a line projected eastward from the mouth of the Anchiyoke River to the Rocky Mountains, and bounded on the north by the parallel fifty-four forty. This was the first subdivision of the land now known as the State of Washington.1 On August 12, 1845 a bill was introduced in the legislative assembly to create two new counties north of the Columbia River and give one the name of Lewis and the other the name of Clark in honor of the famous explorers. The bill passed but with a rider attached substituting the name Vancouver in place of I,ewis and Clark, and defining one district instead of two counties. Thus, Vancouver District .was created to include "all that portion of the Territory of Oregon lying north of the middle of the main channel of the Columbia River."2 At the next session of the assembly the eastern boundary was changed from the Rockies to the Columbia River.3 On December 18, 1845, Mr. -

Tribal Perspectives Teacher Guide

Teacher Guide for 7th – 12th Grades for use with the educational DVD Tribal Perspectives on American History in the Northwest First Edition The Regional Learning Project collaborates with tribal educators to produce top quality, primary resource materials about Native Americans and regional history. Teacher Guide prepared by Bob Boyer, Shana Brown, Kim Lugthart, Elizabeth Sperry, and Sally Thompson © 2008 Regional Learning Project, The University of Montana, Center for Continuing Education Regional Learning Project at the University of Montana–Missoula grants teachers permission to photocopy the activity pages from this book for classroom use. No other part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher. For more information regarding permission, write to Regional Learning Project, UM Continuing Education, Missoula, MT 59812. Acknowledgements Regional Learning Project extends grateful acknowledgement to the tribal representatives contributing to this project. The following is a list of those appearing in the DVD Tribal Perspectives on American History in the Northwest, from interviews conducted by Sally Thompson, Ph.D. Lewis Malatare (Yakama) Lee Bourgeau (Nez Perce) Allen Pinkham (Nez Perce) Julie Cajune (Salish) Pat Courtney Gold (Wasco) Maria Pascua (Makah) Armand Minthorn (Cayuse–Nez Perce) Cecelia Bearchum (Walla Walla–Yakama) Vernon Finley -

Legislative Assembly Territory of Washington

ACTS. OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE TERRITORY OF WASHINGTON, PASSED AT THE THIRD REGULAR SESSION, BEGUN AND HELD AT OLYMPIA, DECEMBER 3, 1855, AND OF TUE INDEPENDENCE OF THE UNITED STATES, THE EIGIPTY-FIRST. PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY. OLYMPIA: GEO. B. GOUDY, PUBLIC PRINTER. 1856. LAWS OF THE TERRITORY OF WASHINGTON, 1855-6. AN ACT TO REPEAL THE LAWS OF OREGON TERRITORY, NOW IN FORCE IN WASH- INGTON TERRITORY. SEc. 1. Oregon territorial laws repealed. County seats and county lines not affected by this act. Proceedings, heretofore commenced, not interfered with. Common law in force in certain eases. 2. Act to take effect from passage. SEc. 1. Be it enacted by the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Washington, That all laws, heretofore in force in this Territory, by virtue of any legislation of the Territory of Oregon, be, and the same are here- by, repealed: Provided, That nothing in this act shall be so construed as to change any county seat, or county lines, established by said laws of Oregon, or to render invalid any proceeding commenced under and by vir- tue of said laws: And provided, further, That the common law, in all civil cases, except where otherwise provided by law, shall be in force. SEc. 2. This act to take effect and be in, force from and after its passage. Passed January 31, 1856. 8 AN ACT TO AMEND AN ACT, TO REGULATE THE PRACTICE AND PROCEEDING IN CIVIL ACTIONS. SEc. 1.' Section 323, of " Civil Practice Act," amended. Manner of taking depositions of non-resident witness. -

An Historical Perspective of Oregon's and Portland's Political and Social

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 3-14-1997 An Historical Perspective of Oregon's and Portland's Political and Social Atmosphere in Relation to the Legal Justice System as it Pertained to Minorities: With Specific Reference to State Laws, City Ordinances, and Arrest and Court Records During the Period -- 1840-1895 Clarinèr Freeman Boston Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons, and the Public Administration Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Boston, Clarinèr Freeman, "An Historical Perspective of Oregon's and Portland's Political and Social Atmosphere in Relation to the Legal Justice System as it Pertained to Minorities: With Specific Reference to State Laws, City Ordinances, and Arrest and Court Records During the Period -- 1840-1895" (1997). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4992. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6868 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Clariner Freeman Boston for the Master of Science in Administration of Justice were presented March 14, 1997, and accepted by the thesis committee and the department. COMMITTEE APPROVAL: Charles A. Tracy, Chair. Robert WLOckwood Darrell Millner ~ Representative of the Office of Graduate Studies DEPARTMENT APPROVAL<: _ I I .._ __ r"'liatr · nistration of Justice ******************************************************************* ACCEPTED FOR PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY BY THE LIBRARY by on 6-LL-97 ABSTRACT An abstract of the thesis of Clariner Freeman Boston for the Master of Science in Administration of Justice, presented March 14, 1997. -

Lake Oswego Portland

Lake Oswego to Portland TRANSIT PROJECT Public scoping report August 2008 Metro People places. Open spaces. Clean air and clean water do not stop at city limits or county lines. Neither does the need for jobs, a thriving economy and good transportation choices for people and businesses in our region. Voters have asked Metro to help with the challenges that cross those lines and affect the 25 cities and three coun- ties in the Portland metropolitan area. A regional approach simply makes sense when it comes to protecting open space, caring for parks, planning for the best use of land, managing garbage disposal and increasing recycling. Metro oversees world-class facilities such as the Oregon Zoo, which contributes to conservation and educa- tion, and the Oregon Convention Center, which benefits the region’s economy Metro representatives Metro Council President – David Bragdon Metro Councilors – Rod Park, District 1; Carlotta Collette, District 2; Carl Hosticka, District 3; Kathryn Harrington, District 4; Rex Burkholder, District 5; Robert Liberty, District 6. Auditor – Suzanne Flynn www.oregonmetro.gov Lake Oswego to Portland Transit Project Public scoping report Table of contents SECTION 1: SCOPING REPORT INTRODUCTION …………………………………......... 1 Introduction Summary of outreach activities Summary of agency scoping comments Public comment period findings Conclusion SECTION 2: PUBLIC SCOPING MEETING ………………………………………………… 7 Summary Handouts SECTION 3: AGENCY SCOPING COMMENTS ………………………………………..... 31 Environmental Protection Agency SECTION 4: PUBLIC