Remembering 1857

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendices Non-Surveyed Applegate Trail Site: East I

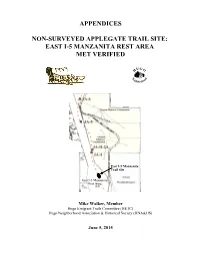

APPENDICES NON-SURVEYED APPLEGATE TRAIL SITE: EAST I-5 MANZANITA REST AREA MET VERIFIED Mike Walker, Member Hugo Emigrant Trails Committee (HETC) Hugo Neighborhood Association & Historical Society (HNA&HS) June 5, 2015 NON-SURVEYED APPLEGATE TRAIL SITE: EAST I-5 MANZANITA REST AREA MET VERIFIED APPENDICES Appendix A. Hugo Neighborhood Association & Historical Society (HuNAHS) Standards for All Emigrant Trail Inventories and Decisions Appendix B. HuNAHS’ Policy for Document Verification & Reliability of Evidence Appendix C. HETC’s Standards: Emigrant Trail Inventories and Decisions Appendix D1. Pedestrian Survey of Stockpile Site South of Chancellor Quarry in the I-5 Jumpoff Joe-Glendale Project, Josephine County (separate web page) Appendix D2. Subsurface Reconnaissance of the I-5 Chancellor Quarry Stockpile Project, and Metal Detector Survey Within the George and Mary Harris 1854 - 55 DLC (separate web page) Appendix D3. May 18, 2011 Email/Letter to James Black, Planner, Josephine County Planning Department (separate web page) Appendix D4. The Rogue Indian War and the Harris Homestead Appendix D5. Future Studies Appendix E. General Principles Governing Trail Location & Verification Appendix F. Cardinal Rules of Trail Verification Appendix G. Ranking the Reliability of Evidence Used to Verify Trial Location Appendix H. Emigrant Trail Classification Categories Appendix I. GLO Surveyors Lake & Hyde Appendix J. Preservation Training: Official OCTA Training Briefings Appendix K. Using General Land Office Notes And Maps To Relocate Trail Related Features Appendix L1. Oregon Donation Land Act Appendix L2. Donation Land Claim Act Appendix M1. Oregon Land Survey, 1851-1855 Appendix M2. How Accurate Were the GLO Surveys? Appendix M3. Summary of Objects and Data Required to Be Noted In A GLO Survey Appendix M4. -

William Henderson Packwood Holds a Unique Place in Oregon History As the Youngest Participant of Oregon's Constitutional Convention of 1857

William Packwood (1832-1917) by Gary Dielman William Henderson Packwood holds a unique place in Oregon history as the youngest participant of Oregon's Constitutional Convention of 1857. This mostly self-educated pioneer became one of Oregon's most versatile entrepreneurs. His occupations included soldier, Indian fighter, miner, cattle rancher, merchant, ditch and road builder, ferry owner, and public servant. He was a founding father of two Baker County mining boom towns—Auburn and Sparta. He is also the great-grandfather of Oregon former Senator Robert Packwood. William and Johanna Packwood, ca. 1870. Packwood was born October 23, 1832, near Mount Vernon, Illinois. The family settled in Sparta for a while and then, when he was fourteen, moved to Springfield, where Packwood clerked in a store, often meeting Abraham Lincoln on his way to work. In 1848, just before his sixteenth birthday, Packwood convinced his father and the army to allow him to enlist. In the summer of 1849, Packwood's company escorted a general and his retinue from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to Sacramento, California. The following year, Packwood was posted to Fort Vancouver. As he sailed from San Francisco to Washington Territory, the schooner Lincoln ran aground in a storm off Coos Bay January 3, 1852. The ship was wrecked, but all aboard made it ashore at the future site of Empire, where Packwood first set foot on Oregon soil. After Packwood's discharge from the army in September 1853, he worked packing, mining, and cattle ranching on the Coquille River. In 1855, Packwood was commissioned as captain of a volunteer company charged with putting down a Rogue River Indian uprising in southeastern Oregon. -

“A Proper Attitude of Resistance”

Library of Congress, sn84026366 “A Proper Attitude of Resistance” The Oregon Letters of A.H. Francis to Frederick Douglass, 1851–1860 PRIMARY DOCUMENT by Kenneth Hawkins BETWEEN 1851 AND 1860, A.H. Francis wrote over a dozen letters to his friend Frederick Douglass, documenting systemic racism and supporting Black rights. Douglass I: “A PROPER ATTITUDE OF RESISTANCE” 1831–1851 published those letters in his newspapers, The North Star and Frederick Douglass’ Paper. The November 20, 1851, issue of Frederick Douglass’ Paper is shown here. In September 1851, when A.H. Francis flourished. The debate over whether and his brother I.B. Francis had just to extend slavery to Oregon contin- immigrated from New York to Oregon ued through the decade, eventually and set up a business on Front Street entangling A.H. in a political feud in Portland, a judge ordered them to between Portland’s Whig newspaper, in letters to Black newspapers, Francis 200 White Oregonians (who signed a leave the territory. He found them in the Oregonian, edited by Thomas explored the American Revolution’s petition to the territorial legislature on violation of Oregon’s Black exclusion Dryer, and Oregon’s Democratic party legacy of rights for Blacks, opposed their behalf), the brothers successfully law, which barred free and mixed-race organ in Salem, the Oregon States- schemes to colonize Africa with free resisted the chief Supreme Court jus- Black people from residence and man, edited by Asahel Bush.2 Francis American Black people, and extolled tice’s expulsion order and negotiated most civil rights. A.H. had been an also continued his collaboration with the opportunities available through accommodations to succeed on the active abolitionist in New York for two Douglass through a series of letters economic uplift and immigration to the far periphery of what Thomas Jefferson decades, working most recently with that Douglass published between American West. -

Congressional. Record

. CONGRESSIONAL. RECORD. PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE FORTY-SEVENTH CONGRESS. SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE. SENATE. Maryland-Arthur P. Gorman and James B. Groome. Massachusetts-Henry L. Dawes and George F. Hoar. MoNDAY, October 10, 1881. Michigan-Omar D. Conger and Thomas W. Ferry. In Minnesota-Alonzo J. Edgerton and Samuel J. R. McMillan. pursuance of the proclamation of September 23, 1881, issued by Missi.sBippi-Jamea Z. George and Lucius Q. C. Lamar. President Arthur (James A. Garfield, the late President ofthe United M'us&uri-Francis M. Cockrell and George G. Vest. Sta.tes, having died on the 19th of September, and the powers and Nebraska-Alvin Saunders and Charles H. VanWyck. duties of the office having, in. conformity with the Constitution, de Nevada-John P. Jones. volved upon Vice-President Arthur) the Senate convened to-day in New Hampshire-Henry W. Blair and Edward H. Rollins. special session at the Capitol in the city of Washington. New Jersey-John R. McPherson and William J. Sewell. PRAYER. North Carolina-Matt. W. Ransom and Zebulon B. Vance. Rev. J. J. BULLOCK, D. D., Chaplain to the Senate, offered the fol Ohio-George H. Pendleton and John Sherman. lowing prayer : Oregon-La Fayette Grover and James H. Slater. Almighty God, our heavenly Father, in obedience to the call of the Pennsylvania-James Donald Cameron and John I. Mitchell. President of the United States, we have met together this day. We Rhode Island-Henry B. Anthony. meet under circumstances of the greatest solemnity, for since our last S&uth Carolina-M. -

Title: the Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher's Guide of 20Fh Century Physics

REPORT NSF GRANT #PHY-98143318 Title: The Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher’s Guide of 20fhCentury Physics DOE Patent Clearance Granted December 26,2000 Principal Investigator, Brian Schwartz, The American Physical Society 1 Physics Ellipse College Park, MD 20740 301-209-3223 [email protected] BACKGROUND The American Physi a1 Society s part of its centennial celebration in March of 1999 decided to develop a timeline wall chart on the history of 20thcentury physics. This resulted in eleven consecutive posters, which when mounted side by side, create a %foot mural. The timeline exhibits and describes the millstones of physics in images and words. The timeline functions as a chronology, a work of art, a permanent open textbook, and a gigantic photo album covering a hundred years in the life of the community of physicists and the existence of the American Physical Society . Each of the eleven posters begins with a brief essay that places a major scientific achievement of the decade in its historical context. Large portraits of the essays’ subjects include youthful photographs of Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, and Richard Feynman among others, to help put a face on science. Below the essays, a total of over 130 individual discoveries and inventions, explained in dated text boxes with accompanying images, form the backbone of the timeline. For ease of comprehension, this wealth of material is organized into five color- coded story lines the stretch horizontally across the hundred years of the 20th century. The five story lines are: Cosmic Scale, relate the story of astrophysics and cosmology; Human Scale, refers to the physics of the more familiar distances from the global to the microscopic; Atomic Scale, focuses on the submicroscopic This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 QMS Mo. 1024-0018 (Rev. 846) '" n i;n r? r United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name Goodwin-Wilkinson Farmhouse other names/site number 2. Location street & number Route 1 , Box 574 N/ LJ not for publication city, town Warrenton 1C- vicinity state Oregon code OR county Clatsop code 007 zip code 97146 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property [x~ private E building(s) Contributing Noncontributing I public-local district i i buildings I public-State site ____ ____ sites I public-Federal C structure ____ ____ structures I I object ____ ____objects 1 i Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register M/A 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this [xj nomination LJ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Bush House Today Lies Chiefly in Its Rich, Unaltered Interior,Rn Which Includes Original Embossed French Wall Papers, Brass Fittings, and Elaborate Woodwork

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Oregon COUNTTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Mari on INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE (Type all entries — complete applica#ie\s&ctipns) / \ ' •• &•••» JAN 211974 COMMON: /W/' .- ' L7 w G I 17 i97«.i< ——————— Bush (Asahel) House —— U^ ——————————— AND/OR HISTORIC: \r«----. ^ „. I.... ; „,. .....,.„„.....,.,.„„,„,..,.,..,..,.,, , ,, . .....,,,.,,,M,^,,,,,,,,M,MM^;Mi,,,,^,,p'K.Qic:r,£: 'i-; |::::V^^:iX.::^:i:rtW^:^ :^^ Sii U:ljif&:ii!\::T;:*:WW:;::^^ STREET AND NUMBER: "^s / .•.-'.••-' ' '* ; , X •' V- ; '"."...,, - > 600 Mission Street s. F. W J , CITY OR TOWN: Oregon Second Congressional Dist. Salem Representative Al TJllman STATE CODE COUNT ^ : CO D E Oreeon 97301 41 Marien Q47 STATUS ACCESSIBLE CATEGORY OWNERSHIP (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC r] District |t] Building SO Public Public Acquisit on: E Occupied Yes: r-, n . , D Restricted G Site Q Structure D Private Q ' n Process ( _| Unoccupied -j . —. _ X~l Unrestricted [ —[ Object | | Both [ | Being Consider ea Q Preservation work ^~ ' in progress ' — I PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) \ | Agricultural | | Government | | Park [~] Transportation l~l Comments | | Commercial CD Industrial | | Private Residence G Other (Specify) Q Educational d] Military Q Religious [ | Entertainment GsV Museum QJ] Scientific ...................... OWNER'S NAME: Ul (owner proponent of nomination) P ) ———————City of Salem————————————————————————————————————————— - ) -

Opening Brief of Intervenors-Appellants Elizabeth Trojan, David Delk, and Ron Buel

FILED July 12, 2019 04:42 AM Appellate Court Records IN THE SUPREME COURT THE STATE OF OREGON In the Matter of Validation Proceeding To Determine the Regularity and Legality of Multnomah County Home Rule Charter Section 11.60 and Implementing Ordinance No. 1243 Regulating Campaign Finance and Disclosure. MULTNOMAH COUNTY, Petitioner-Appellant, and ELIZABETH TROJAN, MOSES ROSS, JUAN CARLOS ORDONEZ, DAVID DELK, JAMES OFSINK, RON BUEL, SETH ALAN WOOLLEY, and JIM ROBISON, Intervenors-Appellants, and JASON KAFOURY, Intervenor, v. ALAN MEHRWEIN, PORTLAND BUSINESS ALLIANCE, PORTLAND METROPOLITAN ASSOCIATION OF REALTORS, and ASSOCIATED OREGON INDUSTRIES, Intervenors-Respondents Multnomah County Circuit Court No. 17CV18006 Court of Appeals No. A168205 Supreme Court No. S066445 OPENING BRIEF OF INTERVENORS-APPELLANTS ELIZABETH TROJAN, DAVID DELK, AND RON BUEL On Certi¡ ed Appeal from a Judgment of the Multnomah County Circuit Court, the Honorable Eric J. Bloch, Judge. caption continued on next page July 2019 LINDA K. WILLIAMS JENNY MADKOUR OSB No. 78425 OSB No. 982980 10266 S.W. Lancaster Road KATHERINE THOMAS Portland, OR 97219 OSB No. 124766 503-293-0399 voice Multnomah County Attorney s Office 855-280-0488 fax 501 SE Hawthorne Blvd., Suite 500 [email protected] Portland, OR 97214 503-988-3138 voice Attorney for Intervenors-Appellants [email protected] Elizabeth Trojan, David Delk, and [email protected] Ron Buel Attorneys for Petitioner-Appellant Multnomah County DANIEL W. MEEK OSB No. 79124 10949 S.W. 4th Avenue GREGORY A. CHAIMOV Portland, OR 97219 OSB No. 822180 503-293-9021 voice Davis Wright Tremaine LLP 855-280-0488 fax 1300 SW Fifth Avenue, Suite 2400 [email protected] Portland, OR 97201 503-778-5328 voice Attorney for Intervenors-Appellants [email protected] Moses Ross, Juan Carlos Ordonez, James Ofsink, Seth Alan Woolley, Attorney for Intervenors-Resondents and Jim Robison i TABLE OF CONTENTS I. -

The Democratic Split During Buchanan's Administration

THE DEMOCRATIC SPLIT DURING BUCHANAN'S ADMINISTRATION By REINHARD H. LUTHIN Columbia University E VER since his election to the presidency of the United States Don the Republican ticket in 1860 there has been speculation as to whether Abraham Lincoln could have won if the Democratic party had not been split in that year.' It is of historical relevance to summarize the factors that led to this division. Much of the Democratic dissension centered in the controversy between President James Buchanan, a Pennsylvanian, and United States Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois. The feud was of long standing. During the 1850's those closest to Buchanan, par- ticularly Senator John Slidell of Louisiana, were personally antagonistic toward Douglas. At the Democratic national conven- tion of 1856 Buchanan had defeated Douglas for the presidential nomination. The Illinois senator supported Buchanan against the Republicans. With Buchanan's elevation to the presidency differences between the two arose over the formation of the cabinet.2 Douglas went to Washington expecting to secure from the President-elect cabinet appointments for his western friends William A. Richardson of Illinois and Samuel Treat of Missouri. But this hope was blocked by Senator Slidell and Senator Jesse D. Bright of Indiana, staunch supporters of Buchanan. Crestfallen, 'Edward Channing, A History of the United States (New York, 1925), vol. vi, p. 250; John D. Hicks, The Federal Union (Boston and New York, 1937), p. 604. 2 Much scholarly work has been done on Buchanan, Douglas, and the Democratic rupture. See Philip G. Auchampaugh, "The Buchanan-Douglas Feud," and Richard R. -

Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882 Jerry Rushford Pepperdine University

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Churches of Christ Heritage Center Jerry Rushford Center 1-1-1998 Christians on the Oregon Trail: Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882 Jerry Rushford Pepperdine University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/heritage_center Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Rushford, Jerry, "Christians on the Oregon Trail: Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882" (1998). Churches of Christ Heritage Center. Item 5. http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/heritage_center/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Jerry Rushford Center at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Churches of Christ Heritage Center by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHRISTIANS About the Author ON THE Jerry Rushford came to Malibu in April 1978 as the pulpit minister for the University OREGON TRAIL Church of Christ and as a professor of church history in Pepperdine’s Religion Division. In the fall of 1982, he assumed his current posi The Restoration Movement originated on tion as director of Church Relations for the American frontier in a period of religious Pepperdine University. He continues to teach half time at the University, focusing on church enthusiasm and ferment at the beginning of history and the ministry of preaching, as well the nineteenth century. The first leaders of the as required religion courses. movement deplored the numerous divisions in He received his education from Michigan the church and urged the unity of all Christian College, A.A. -

Report on the History of Matthew P. Deady and Frederick S. Dunn

Report on the History of Matthew P. Deady and Frederick S. Dunn By David Alan Johnson Professor, Portland State University former Managing Editor (1997-2014), Pacific Historical Review Quintard Taylor Emeritus Professor and Scott and Dorothy Bullitt Professor of American History. University of Washington Marsha Weisiger Julie and Rocky Dixon Chair of U.S. Western History, University of Oregon In the 2015-16 academic year, students and faculty called for renaming Deady Hall and Dunn Hall, due to the association of Matthew P. Deady and Frederick S. Dunn with the infamous history of race relations in Oregon in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. President Michael Schill initially appointed a committee of administrators, faculty, and students to develop criteria for evaluating whether either of the names should be stripped from campus buildings. Once the criteria were established, President Schill assembled a panel of three historians to research the history of Deady and Dunn to guide his decision-making. The committee consists of David Alan Johnson, the foremost authority on the history of the Oregon Constitutional Convention and author of Founding the Far West: California, Oregon, Nevada, 1840-1890 (1992); Quintard Taylor, the leading historian of African Americans in the U.S. West and author of several books, including In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West, 1528-1990 (1998); and Marsha Weisiger, author of several books, including Dreaming of Sheep in Navajo Country (2009). Other historians have written about Matthew Deady and Frederick Dunn; although we were familiar with them, we began our work looking at the primary sources—that is, the historical record produced by Deady, Dunn, and their contemporaries. -

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 BLACK JACK BATTLEFIELD Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Black Jack Battlefield Other Name/Site Number: Evergreen Stock Farm; Pearson, Robert Hall, Farm; Sites #04000365, 04001373, 04500000389 2. LOCATION Street & Number: U.S. Highway 56 and County Road 2000, 3 miles east of Baldwin City Not for publication: City/Town: Baldwin City Vicinity: X State: Kansas County: Douglas Code: 045 Zip Code: 66006 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): ___ Public-Local: X District: ___ Public-State: ___ Site: X _ Public-Federal: ___ Structure: ___ Object: ___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 0 6 buildings 3 0 sites 0 3 structures 0 6 objects 3 15 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 6 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 BLACK JACK BATTLEFIELD Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60.