Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2.04.26 Fecal Analysis in the Diagnosis of Intestinal Dysbiosis and Irritable Bowel Syndrome

MEDICAL POLICY – 2.04.26 Fecal Analysis in the Diagnosis of Intestinal Dysbiosis and Irritable Bowel Syndrome BCBSA Ref. Policy: 2.04.26 Effective Date: July 1, 2021 RELATED MEDICAL POLICIES: Last Revised: June 8, 2021 None Replaces: N/A Select a hyperlink below to be directed to that section. POLICY CRITERIA | DOCUMENTATION REQUIREMENTS | CODING RELATED INFORMATION | EVIDENCE REVIEW | REFERENCES | HISTORY ∞ Clicking this icon returns you to the hyperlinks menu above. Introduction Intestinal dysbiosis is a condition that occurs when the microorganisms in the digestive tract are out of balance. This condition is believed to cause diseases of the digestive tract, including poor nutrient absorption, overgrowth of certain bacteria, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Symptoms of these digestive problems are similar and may include: abdominal pain, excess gas, bloating, and changes in bowel movements (constipation or diarrhea, or both). One method of diagnosing digestive disorders is by testing a fecal sample. Using fecal analysis to diagnose intestinal dysbiosis, IBS, malabsorption, or small intestinal overgrowth of bacteria is unproven (investigational). More studies are needed to see if this testing improves health outcomes. Note: The Introduction section is for your general knowledge and is not to be taken as policy coverage criteria. The rest of the policy uses specific words and concepts familiar to medical professionals. It is intended for providers. A provider can be a person, such as a doctor, nurse, psychologist, or dentist. A provider also can be a place where medical care is given, like a hospital, clinic, or lab. This policy informs them about when a service may be covered. -

Publicly Accessible Toilets After COVID-19 a 2021 Update to Inclusive Design Guidance

PAGE 1 Publicly Accessible Toilets after COVID-19 A 2021 update to inclusive design guidance Imran Nazerali, Gail Ramster and Jo-Anne Bichard PAGE 2 Contents 03 INTRODUCTION 04 Why this matters 05 People profiles 06 Types of toilet and access 08 COMMUNICATION 12 INCLUSIVE TOILET DESIGN 20 MAINTAINING HYGIENE 22 References 24 More Information 25 Acknowledgements PAGE 3 Introduction Publicly Accessible Toilets after COVID-19 (2021) Publicly Accessible Toilets: An Inclusive Design Guide (2011) The pandemic has shed light on the importance of publicly accessible toilets to people in the UK. In this Our original design guide - available for free update to Publicly Acc essible Toilets: An Inclusive download (pdf) - shares ideas large and small to Design Guide (see panel, right), we show how future make public toilets more inclusive. toilets can be designed to be more hygienic, and also more accessible and inclusive, as a critical part of Written by Gail Ramster (née Knight) and Jo-Anne public health infrastructure. Bichard at the Royal College of Art, it draws on their experience in public toilet design research. This update revisits previous guidance about areas The guide shares the difficulties that many people of publicly accessible toilet design and provision face when trying to find and use the UK’s current affected by COVID-19, including: public toilet provision. It focuses on differences in how to share information about a facility with age and ability, and draws attention to the needs the public, including gathering feedback; of people with conditions that affect continence. inclusive improvements to toilet design that also minimise transmission of viruses; how to improve and communicate levels of hygiene. -

An Osteopathic Approach to Reduction of Readmissions for Neonatal Jaundice

Osteopathic Family Physician (2013) 5, 17–23 REVIEW ARTICLE An osteopathic approach to reduction of readmissions for neonatal jaundice Rachel Click, DO,a Julie Dahl-Smith, DO,a Lindsay Fowler, DO,a Jacqueline DuBose, MD,a Margi Deneau-Saxton, RN, CCCE, CIMI, CLC, CPD,b Jennifer Herbert, MDc From aGeorgia Health Sciences University, Medical College of Georgia, Department of Family Medicine, GA; bGeorgia Health System, OB Labor and Delivery, GA; and cUniversity Primary Care, Evans, GA. KEYWORDS: Jaundice is a potentially life-threatening condition that continues to affect at-risk newborns, accounting Breastfeeding; for continued hospital readmissions. As family physicians, we should be cognizant of neonates who may Jaundice; be at risk for jaundice, including those with pathologic jaundice as well as newborns of breastfeeding Prevention; mothers, and ensure sufficient intervention is taken to help prevent further elevations in bilirubin levels. Hyperbilirubinemia; Interventions are likely to include evaluation for sepsis, education regarding feeding frequencies for both Neonatal massage breast- and bottle-fed neonates, reviewing maternal and hematologic risk factors for neonatal jaundice, and considering inborn errors of metabolism. An additional measure family physicians may consider is that of neonatal massage for those with elevated bilirubin levels. Neonatal massage, though not widely used, has been proven to promote excess bilirubin excretion, thus decreasing length of hospital stay; all the while, providing an intervention that allows parents to take an active role. r 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction morbidity rate with bilirubin 4 20 mg/dL. “It has been estimated that the risk of kernicterus in infants with total Jaundice is a product of excess bilirubin (a product of serum bilirubin (TSB) greater than 30 mg/dL is about 1 in broken down red blood cells), which manifests as a 7 infants”.1 Less serious complications of hyperbilirubine- yellowing of the skin and eyes. -

INFORMED CARING JAUNDICE Neonatal Jaundice BILIARY

1 INFORMED CARING Situations with Adults and Children with Gallbladder, Liver and Pancreatic Disorders 2 JAUNDICE ä Does NOT mean hepatitis ä Increased breakdown of RBCs ä Altered bilirubin breakdown ä Impeded flow through liver or bile duct ä First seen in sclera, then skin 3 Neonatal Jaundice ä Not liver failure ä RBC breakdown ä Phototherapy 4 BILIARY ATRESIA ä Jaundice 2-3 weeks after birth ä Easy bruising ä Stools putty like ä Tea colored urine ä Abdominal/organ distension 5 4 F’s of Gallbladder ä Fair ä Fat X size of person X amount in diet ä Fertile X BCP X Multiparity ä Forty 6 Cholelithiasis ä Calculi within the duct or gallbladder ä Severe colicky, cramp-like pain X radiates to shoulder blade X Murphy's sign ä Cholecystitis: inflammation X Can be caused by trauma, fasting, TPN or abdominal surgery 7 Diagnostic Studies ä Ultrasound of abdomen 1 X not for the obese ä HIDA scan X nuclear medicine ä Cholangiograms X endoscopic X transvenous X intraoperative 8 Post-op Care ä High abdominal incision X respiratory compromise ä T-tube X patients need to know how to empty it X may clamp it prior to removal X caution not dislodged with movements ä NO Morphine X spasms of sphincter of Oddi 9 Post-op Nutrition ä Limited fat in diet X can have rapid transit times ä Potential fat soluble vitamin deficit X A, D, E and K ä Weight loss diet 10 LIVER FAILURE ä Cirrhosis ä Drug toxicity X acetaminophen, anesthetics, HCTZ, chemotherapy ä Infection ä Cancer ä ETOH is single most linked cause 11 LIVER FAILURE S/S ä Don’t show up until 80-90% failed -

Symptomatic Approach to Gas, Belching and Bloating 21

20 Osteopathic Family Physician (2019) 20 - 25 Osteopathic Family Physician | Volume 11, No. 2 | March/April, 2019 Gennaro, Larsen Symptomatic Approach to Gas, Belching and Bloating 21 Review ARTICLE to escape. This mechanism prevents the stomach from becoming IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME (IBS) Symptomatic Approach to Gas, Belching and Bloating damaged by excessive dilation.2 IBS is abdominal pain or discomfort associated with altered with OMT Treatment Options Many patients with GERD report increased belching. Transient bowel habits. It is the most commonly diagnosed GI disorder lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxation is the major and accounts for about 30% of all GI referrals.7 Criteria for IBS is recurrent abdominal pain at least one day per week in the Carly Gennaro, DO1; Helaine Larsen, DO1 mechanism for both belching and GERD. Recent studies have shown that the number of belches is related to the number of last three months associated with at least two of the following: times someone swallows air. These studies have concluded that 1) association with defecation, 2) change in stool frequency, 1 Good Samaritan Hospital Medical Center, West Islip, NY patients with GERD swallow more air in response to heartburn and 3) change in stool form. Diagnosis should be made using these therefore belch more frequently.3 There is no specific treatment clinical criteria and limited testing. Common symptoms are for belching in GERD patients, so for now, physicians continue to abdominal pain, bloating, alternating diarrhea and constipation, treat GERD with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and histamine-2 and pain relief after defecation. Pain can be present anywhere receptor antagonists with the goal of suppressing heartburn and in the abdomen, but the lower abdomen is the most common KEYWORDS: ABSTRACT: Intestinal gas production is a normal physiologic progress. -

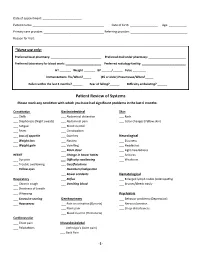

Patient Review of Systems Please Mark Any Condition with Which You Have Had Significant Problems in the Last 6 Months

Date of appointment: ________________________ Patient name: ____________________________________________ Date of birth: _________________ Age: ___________ Primary care provider: _____________________________________ Referring provider: ___________________________________ Reason for Visit: _____________________________________________________________________________________________ *Nurse use only: Preferred local pharmacy: _______________________________ Preferred mail order pharmacy: _______________________ Preferred laboratory for blood work: ______________________ Preferred radiology facility: ___________________________ HT _______ Weight _______ BP ______/______ Pulse ________ Immunizations: Flu/When?_____ (65 or older) Pneumovax/When?_____ Fallen within the last 3 months? ______ Fear of falling?______ Difficulty ambulating? ______ Patient Review of Systems Please mark any condition with which you have had significant problems in the last 6 months: Constitution Gastrointestinal Skin ___ Chills ___ Abdominal distention ___ Rash ___ Diaphoresis (Night sweats) ___ Abdominal pain ___ Color changes (Yellow skin) ___ Fatigue ___ Blood in stool ___ Fever ___ Constipation ___ Loss of appetite ___ Diarrhea Neurological ___ Weight loss ___ Nausea ___ Dizziness ___ Weight gain ___ Vomiting ___ Headaches ___ Black stool ___ Light-headedness HEENT ___ Change in bowel habits ___ Seizures ___ Eye pain ___ Difficulty swallowing ___ Weakness ___ Trouble swallowing ___ Gas/flatulence ___ Yellow eyes ___ Heartburn/indigestion ___ Bowel accidents Hematological -

Neo-Normativity, the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, and Latrinalia: the Demonstration of a Concept on Non-Heterosexual Performativities

NEO-NORMATIVITY, THE SYDNEY GAY AND LESBIAN MARDI GRAS, AND LATRINALIA: THE DEMONSTRATION OF A CONCEPT ON NON-HETEROSEXUAL PERFORMATIVITIES A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy EDGAR YUE LAP LIU School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences Faculty of Science University of New South Wales Sydney, Australia September 2008 Declaration I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person, nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project’s design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged. Edgar Yue Lap LIU COPYRIGHT STATEMENT ‘I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. -

Traveller's Diarrhoea (TD) Is the Commonest Health

Diarrhoea • THEME Traveller's diarrhoea BACKGROUND There has been little if any Traveller's diarrhoea (TD) is the commonest health change in the incidence of traveller's diarrhoea problem facing travellers to less developed countries over the past 20 years. of the world. It is costly to both the traveller (time lost) and the host country (eg. cancelled activities). OBJECTIVE This article aims to provide a basic understanding on why travellers are more likely to Definition experience diarrhoea during travel. Classic TD is described as three or more loose bowel DISCUSSION In a 20 minute pretravel actions with at least one of the following accompanying consultation time is precious, and providing symptoms: nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps or information on traveller's diarrhoea often has pain, fever or blood in the stools. Lesser degrees a low priority over prescribing the necessary vaccinations and discussing antimalarials. (moderate or mild) of TD are also described. Severity is Bob Kass, Travellers do not follow the rules of eating and usually defined by the number of bowel actions per 24 drinking safely, and diarrhoea is common. 'What hour period (severe >6). According to the World Health MBBS, MRCP (UK), MScMCH, Organisation, symptoms lasting less than 14 days may to do in the event of illness' is an important DCH, FAFPHM, consideration. Presumptive treatment should be defined as 'acute diarrhoea', and those lasting more is a consultant, be offered to all travellers whose itinerary and than 14 days 'persistent diarrhoea'.1 International Public activities put them at risk. Between 30 and 50% of travellers will be affected Health Medicine, Rede-Health in a 2 week overseas stay, with approximately 12% International. -

Type 2 Diabetes SCAN Formulary Drugs

Pharmacologic Agents for Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes SCAN Formulary Drugs 2020 2021 Risk for Dosing & Drug- Drug Medication Formulary Formulary Adverse Drug Reactions Administration Interactions Tier UM Tier UM * Biguanides 500 – 850 mg Nausea/ vomiting, GI upset, metallic taste, metformin tabs 1 1 QD - TID diarrhea, flatulence, lactic acidosis (rare) metformin er Neutral 500 – 2000 mg Nausea/ vomiting, GI upset, diarrhea, flatulence, uncoated tabs 1 1 daily lactic acidosis 500 mg & 750 mg Sulfonylureas Dizziness, headache, hypoglycemia, nausea, glimepiride 1 1 1 – 8 mg daily weight gain 2.5 – 20 mg Rash, diarrhea, dizziness, headache, diarrhea, glipizide 1 1 daily Moderate hypoglycemia, nausea, weight gain Asthenia, headache, dizziness, rash, nausea, glipizide er 1 1 5 – 20 mg daily hypoglycemia, weight gain glipizide / 2.5 / 500 mg Rash, diarrhea, dizziness, headache, nausea, 1 1 Moderate metformin tabs BID flatulence, hypoglycemia, lactic acidosis Thiazolidinediones & Thiazolidinedione Combination Agents 15 – 45 mg Anemia, edema, weight gain, headache, myalgia, pioglitazone 1 1 daily bone fracture, heart failure 15 / 500 mg – pioglitazone / Rash, diarrhea, dizziness, headache, nausea, 2 2 45 / 1500mg metformin Neutral flatulence, hypoglycemia, lactic acidosis daily 15 / 500 mg – pioglitazone / Anemia, edema, weight gain, headache, myalgia, 2 [QL] 2 [QL] 45 / 2550 mg glimepiride dizziness, hypoglycemia, nausea daily R. Brower and N. Nguyen rev. 11/2012; R. Brower rev. 11/2013, 9/2014, 11/2015; D. Yoon rev 8/2016, 11/2016, 8/2017; K. -

Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Diet

Irritable bowel syndrome and diet What is irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)? IBS is a very common condition. It describes a wide range of symptoms that vary from one person to another and can be worse for some people than others. The most common symptoms are: • wind and/or bloating • feeling the need to open the bowels even after • diarrhoea or constipation, or both having just been to the toilet • low abdominal pain, which may ease after opening the • a feeling of urgency bowels or be accompanied by a change in bowel habit • feeling that your symptoms are worse after or stool appearance eating. • passing mucus If you have any of the following symptoms consult your doctor immediately: unintentional and unexplained weight loss; rectal bleeding; a family history of bowel or ovarian cancer; if you are over 60 years old, a change in bowel habit to looser and/or more frequent stools for more than 6 weeks. Before attempting to manage symptoms via your diet, it is important to rule our other medical conditions, and to have a diagnosis established by your doctor or healthcare professional. Ensure that you: Helpful hints: • eat regular meals • keep a food and symptom diary to see if • do not skip meals or eat late at night diet affects your symptoms. Remember • take your time when eating meals symptoms may not be caused by the food • sit down to eat and chew your food well you have just eaten, but what you ate • take regular exercise – for example, earlier that day or the day before. walking, cycling or swimming • give your bowels time to adjust to any • make time to relax. -

The Semiotics of Waste World Cultures: on Traveling, Toilets, and Belonging

CULTURA CULTURA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY OF CULTURE CULTURA AND AXIOLOGY Founded in 2004, Cultura. International Journal of Philosophy of 2012 Culture and Axiology is a semiannual peer-reviewed journal devo- 2 2012 Vol IX No 2 ted to philosophy of culture and the study of value. It aims to pro- mote the exploration of different values and cultural phenomena in regional and international contexts. The editorial board encourages OLOGY the submission of manuscripts based on original research that are I judged to make a novel and important contribution to understan- LOSOPHY OF I ding the values and cultural phenomena in the contempo rary world. CULTURE AND AX AND CULTURE ONAL JOURNAL OF PH I INTERNAT ISBN 978-3-631-62905-5 www.peterlang.de PETER LANG CULTURA 2012_262905_VOL_9_No2_GR_A5Br.indd 1 16.11.12 12:39:44 Uhr CULTURA CULTURA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY OF CULTURE CULTURA AND AXIOLOGY Founded in 2004, Cultura. International Journal of Philosophy of 2014 Culture and Axiology is a semiannual peer-reviewed journal devo- 1 2014 Vol XI No 1 ted to philosophy of culture and the study of value. It aims to pro- mote the exploration of different values and cultural phenomena in regional and international contexts. The editorial board encourages the submission of manuscripts based on original research that are judged to make a novel and important contribution to understan- ding the values and cultural phenomena in the contempo rary world. CULTURE AND AXIOLOGY CULTURE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY INTERNATIONAL www.peterlang.com CULTURA 2014_265846_VOL_11_No1_GR_A5Br.indd.indd 1 14.05.14 17:43 Cultura. -

Standard of Care: Anorectal Disorders ICD 10 Codes

Department of Rehabilitation Services Physical Therapy Standard of Care: Anorectal Disorders ICD 10 Codes: Constipation (outlet dysfunction): K5902 Anal Spasm: K594 Constipation (NEC): K5900 Other Specified Diseases of Anus or Rectum: K6289 Fecal Incontinence (full): R159 Fecal Incontinence (incomplete emptying): R150 Fecal Incontinence (smearing): R151 Fecal Incontinence (fecal urgency): R152 Additional ICD-10 codes that may be used to address common coexisting impairments: Pelvic muscle wasting: N8184 Rectocele: N816 Muscle spasm: M62838 Case Type / Diagnosis: dyssynergic defecation (outlet dysfunction); slow transit constipation, fecal incontinence, anorectal pain/Levator Ani Syndrome, proctalgia fugax Anorectal disorders encompass multiple diagnoses including: dyssynergic defecation, fecal incontinence and levator ani syndrome, all of which are evaluated and treated in pelvic health physical therapy. The current Rome IV diagnostic criterion (released in May 2016), which is the standard for clinical practice and research for functional gastrointestinal disorders, recognizes several anorectal disorders, including: fecal incontinence, functional anorectal pain, and functional defecation disorders and functional constipation.1 Please refer to the tables below for complete review of the Rome IV diagnostic criteria for each condition. 1,2 . Anorectal disorders are common and affect up to 25% of the adult and pediatric population, causing a significant negative impact on quality of life and a burden to health care. 3 The exact definition of fecal incontinence and anal incontinence is important in differential diagnosis for the pelvic floor physical therapist. Fecal incontinence, (FI) as defined by Bharucha, is uncontrolled passage of fecal material recurring for less than or equal to 3 months and is not considered a medical problem before age four.