Emerging Options for the Management of Travelers' Diarrhea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2.04.26 Fecal Analysis in the Diagnosis of Intestinal Dysbiosis and Irritable Bowel Syndrome

MEDICAL POLICY – 2.04.26 Fecal Analysis in the Diagnosis of Intestinal Dysbiosis and Irritable Bowel Syndrome BCBSA Ref. Policy: 2.04.26 Effective Date: July 1, 2021 RELATED MEDICAL POLICIES: Last Revised: June 8, 2021 None Replaces: N/A Select a hyperlink below to be directed to that section. POLICY CRITERIA | DOCUMENTATION REQUIREMENTS | CODING RELATED INFORMATION | EVIDENCE REVIEW | REFERENCES | HISTORY ∞ Clicking this icon returns you to the hyperlinks menu above. Introduction Intestinal dysbiosis is a condition that occurs when the microorganisms in the digestive tract are out of balance. This condition is believed to cause diseases of the digestive tract, including poor nutrient absorption, overgrowth of certain bacteria, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Symptoms of these digestive problems are similar and may include: abdominal pain, excess gas, bloating, and changes in bowel movements (constipation or diarrhea, or both). One method of diagnosing digestive disorders is by testing a fecal sample. Using fecal analysis to diagnose intestinal dysbiosis, IBS, malabsorption, or small intestinal overgrowth of bacteria is unproven (investigational). More studies are needed to see if this testing improves health outcomes. Note: The Introduction section is for your general knowledge and is not to be taken as policy coverage criteria. The rest of the policy uses specific words and concepts familiar to medical professionals. It is intended for providers. A provider can be a person, such as a doctor, nurse, psychologist, or dentist. A provider also can be a place where medical care is given, like a hospital, clinic, or lab. This policy informs them about when a service may be covered. -

Current Concepts in Management of Outlet Obstruction

Current Concepts in Management of Outlet Obstruction A. Infantino, R. Bellomo, F. Galanti, L. Pisegna Cerone Outlet constipation is often characterized by dis- ical defects should always be considered. abling symptoms consisting of the strenuous Incidences of 33% of occult rectal prolapse, 1.7% effort to expel stools, a feeling of incomplete of sigmoidocele, and 10% of anismus have been evacuation, rectal tenesmus and a repeated call defecographically demonstrated after a clinical to toilet, digitations, and the necessity of enemas diagnosis of rectocele and obstructed defecation and/or suppositories [1]. It is related to multiple [4]. This is very important because of the subse- alterations, variously associated and in different quent different approaches: conservative for degrees, of the organs of the pelvis and per- anismus or surgical intervention for other condi- ineum: rectocele, rectal occult-mucosal or full- tions. thickness prolapse, and enterocele. Synchronous anatomic alterations in the urogynecological sector can also be found: uterine, vaginal, and Rectal Intussusception bladder prolapses [2]. A unique pathophysiolog- ic theory has been suggested but not yet demon- Rectal intussusception is often difficult to diag- strated [3]. As a consequence of the variability of nose. Radiological findings that can be indicative the affected organs, great difficulty in reaching a of rectal intussusception can be found also in diagnosis exists, and the management and treat- healthy people [5, 6]. Even the interpretation of ment of outlet constipation is, to date, far from radiological images is still a controversial issue being standardized. [4, 7–10]. There is open discussion as to whether magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can add more information than cystocolpodefecography Clinical Conditions [9, 10], which remains the most useful and sim- plest test. -

Traveler's Diarrhea

Traveler’s Diarrhea JOHNNIE YATES, M.D., CIWEC Clinic Travel Medicine Center, Kathmandu, Nepal Acute diarrhea affects millions of persons who travel to developing countries each year. Food and water contaminated with fecal matter are the main sources of infection. Bacteria such as enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli, enteroaggregative E. coli, Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Shigella are common causes of traveler’s diarrhea. Parasites and viruses are less common etiologies. Travel destination is the most significant risk factor for traveler’s diarrhea. The efficacy of pretravel counseling and dietary precautions in reducing the incidence of diarrhea is unproven. Empiric treatment of traveler’s diarrhea with antibiotics and loperamide is effective and often limits symptoms to one day. Rifaximin, a recently approved antibiotic, can be used for the treatment of traveler’s diarrhea in regions where noninvasive E. coli is the predominant pathogen. In areas where invasive organisms such as Campylobacter and Shigella are common, fluoroquinolones remain the drug of choice. Azithromycin is recommended in areas with qui- nolone-resistant Campylobacter and for the treatment of children and pregnant women. (Am Fam Physician 2005;71:2095-100, 2107-8. Copyright© 2005 American Academy of Family Physicians.) ILLUSTRATION BY SCOTT BODELL ▲ Patient Information: cute diarrhea is the most com- mised and those with lowered gastric acidity A handout on traveler’s mon illness among travelers. Up (e.g., patients taking histamine H block- diarrhea, written by the 2 author of this article, is to 55 percent of persons who ers or proton pump inhibitors) are more provided on page 2107. travel from developed countries susceptible to traveler’s diarrhea. -

COVID-19 Mrna Pfizer- Biontech Vaccine Analysis Print

COVID-19 mRNA Pfizer- BioNTech Vaccine Analysis Print All UK spontaneous reports received between 9/12/20 and 22/09/21 for mRNA Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine. A report of a suspected ADR to the Yellow Card scheme does not necessarily mean that it was caused by the vaccine, only that the reporter has a suspicion it may have. Underlying or previously undiagnosed illness unrelated to vaccination can also be factors in such reports. The relative number and nature of reports should therefore not be used to compare the safety of the different vaccines. All reports are kept under continual review in order to identify possible new risks. Report Run Date: 24-Sep-2021, Page 1 Case Series Drug Analysis Print Name: COVID-19 mRNA Pfizer- BioNTech vaccine analysis print Report Run Date: 24-Sep-2021 Data Lock Date: 22-Sep-2021 18:30:09 MedDRA Version: MedDRA 24.0 Reaction Name Total Fatal Blood disorders Anaemia deficiencies Anaemia folate deficiency 1 0 Anaemia vitamin B12 deficiency 2 0 Deficiency anaemia 1 0 Iron deficiency anaemia 6 0 Anaemias NEC Anaemia 97 0 Anaemia macrocytic 1 0 Anaemia megaloblastic 1 0 Autoimmune anaemia 2 0 Blood loss anaemia 1 0 Microcytic anaemia 1 0 Anaemias haemolytic NEC Coombs negative haemolytic anaemia 1 0 Haemolytic anaemia 6 0 Anaemias haemolytic immune Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia 9 0 Anaemias haemolytic mechanical factor Microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia 1 0 Bleeding tendencies Haemorrhagic diathesis 1 0 Increased tendency to bruise 35 0 Spontaneous haematoma 2 0 Coagulation factor deficiencies Acquired haemophilia -

Post-Operative Clinical, Manometric, and Defecographic Findings in Patients Undergoing Unsuccessful STARR Operation for Obstructed Defecation

International Journal of Colorectal Disease (2019) 34:837–842 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-019-03263-9 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Post-operative clinical, manometric, and defecographic findings in patients undergoing unsuccessful STARR operation for obstructed defecation A. Picciariello1 & V. Papagni1 & G. Martines1 & M. De Fazio1 & R. Digennaro1 & D. F. Altomare1 Accepted: 6 February 2019 /Published online: 19 February 2019 # Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Aim To evaluate the reason for failure of STARR (stapled transanal rectal resection) operation for obstructed defecation. Methods A retrospective study (June 2012–December 2017) was performed using a prospectively maintained database of patients who underwent STARR operation for ODS (obstructed defecation syndrome), complaining of persisting or de novo occurrence of pelvic floor dysfunctions. Postoperative St Mark’s and ODS scores were evaluated. AVASwas used to score pelvic pain. Patients’ satisfaction was estimated administering the CPGAS (clinical patient grading assessment scale) questionnaire. Objective evaluation was performed by dynamic proctography and anorectal manometry. Results Ninety patients (83.3% females) operated for ODS using STARR technique were evaluated. Median ODS score was 19 while 20 patients (22%) reported de novo fecal urgency and 4 patients a worsening of their preoperative fecal incontinence. Dynamic proctography performed in 54/90 patients showed a significant (> 3.0 cm) rectocele in 19 patients, recto-rectal intussusception in 10 patients incomplete emptying in 24 patients. When compared with internal normal standards, anorectal manometry showed decreased rectal compliance and maximum tolerable volume in patients with urgency. Nine patients reported a persistent postoperative pelvic pain (median VAS score 6). Conclusion Failure of STARR to treat ODS, documented by persisting ODS symptoms, fecal urgency, or chronic pelvic pain, is often justified by the persistence or de novo onset of alteration of the anorectal anatomy at defecation. -

An Osteopathic Approach to Reduction of Readmissions for Neonatal Jaundice

Osteopathic Family Physician (2013) 5, 17–23 REVIEW ARTICLE An osteopathic approach to reduction of readmissions for neonatal jaundice Rachel Click, DO,a Julie Dahl-Smith, DO,a Lindsay Fowler, DO,a Jacqueline DuBose, MD,a Margi Deneau-Saxton, RN, CCCE, CIMI, CLC, CPD,b Jennifer Herbert, MDc From aGeorgia Health Sciences University, Medical College of Georgia, Department of Family Medicine, GA; bGeorgia Health System, OB Labor and Delivery, GA; and cUniversity Primary Care, Evans, GA. KEYWORDS: Jaundice is a potentially life-threatening condition that continues to affect at-risk newborns, accounting Breastfeeding; for continued hospital readmissions. As family physicians, we should be cognizant of neonates who may Jaundice; be at risk for jaundice, including those with pathologic jaundice as well as newborns of breastfeeding Prevention; mothers, and ensure sufficient intervention is taken to help prevent further elevations in bilirubin levels. Hyperbilirubinemia; Interventions are likely to include evaluation for sepsis, education regarding feeding frequencies for both Neonatal massage breast- and bottle-fed neonates, reviewing maternal and hematologic risk factors for neonatal jaundice, and considering inborn errors of metabolism. An additional measure family physicians may consider is that of neonatal massage for those with elevated bilirubin levels. Neonatal massage, though not widely used, has been proven to promote excess bilirubin excretion, thus decreasing length of hospital stay; all the while, providing an intervention that allows parents to take an active role. r 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction morbidity rate with bilirubin 4 20 mg/dL. “It has been estimated that the risk of kernicterus in infants with total Jaundice is a product of excess bilirubin (a product of serum bilirubin (TSB) greater than 30 mg/dL is about 1 in broken down red blood cells), which manifests as a 7 infants”.1 Less serious complications of hyperbilirubine- yellowing of the skin and eyes. -

Endoscopic Characteristics and Causes of Misdiagnosis of Intestinal Schistosomiasis

MOLECULAR MEDICINE REPORTS 8: 1089-1093, 2013 Endoscopic characteristics and causes of misdiagnosis of intestinal schistosomiasis CHUNCUI YE, SHIYUN TAN, LIN JIANG, MING LI, PENG SUN, LEI SHEN and HESHENG LUO Department of Gastroenterology, Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, Hubei 430060, P.R. China Received February 21, 2013; Accepted July 27, 2013 DOI: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1648 Abstract. The aim of this study was to determine the clinical Introduction and endoscopic manifestations, and pathological character- istics of intestinal schistosomiasis in China, in order to raise Schistosomiasis is one of the most widespread parasitic infec- awareness of intestinal schistosomiasis and prevent misdi- tions worldwide. The three predominant schistosome species agnosis and missed diagnosis. The retrospective analysis of identified to infect humans are Schistosoma haematobium clinical and endoscopic manifestations, and histopathological (endemic in Africa and the eastern Mediterranean), S. mansoni characteristics, were conducted for 96 patients with intestinal (endemic in Africa, the Middle East, the Caribbean and South schistosomiasis. Among these patients, 21 lived in areas that America) and S. japonicum (endemic mainly in China, Japan were not infected with Schistosoma and 25 (26%) had no history and the Philippines) (1). It is estimated that 843,007 individuals of schistosome infection or contact with infected water. These in China are infected with S. japonicum (2). Intestinal schis- patients were mainly hospitalized due to symptoms of diarrhea, tosomiasis is an acute or chronic, specific enteropathy caused mucus and bloody purulent stool. Sixteen cases were of the by the deposition of schistosome ovum on the colon and rectal acute enteritis type, and colonoscopy results determined hyper- walls. -

INFORMED CARING JAUNDICE Neonatal Jaundice BILIARY

1 INFORMED CARING Situations with Adults and Children with Gallbladder, Liver and Pancreatic Disorders 2 JAUNDICE ä Does NOT mean hepatitis ä Increased breakdown of RBCs ä Altered bilirubin breakdown ä Impeded flow through liver or bile duct ä First seen in sclera, then skin 3 Neonatal Jaundice ä Not liver failure ä RBC breakdown ä Phototherapy 4 BILIARY ATRESIA ä Jaundice 2-3 weeks after birth ä Easy bruising ä Stools putty like ä Tea colored urine ä Abdominal/organ distension 5 4 F’s of Gallbladder ä Fair ä Fat X size of person X amount in diet ä Fertile X BCP X Multiparity ä Forty 6 Cholelithiasis ä Calculi within the duct or gallbladder ä Severe colicky, cramp-like pain X radiates to shoulder blade X Murphy's sign ä Cholecystitis: inflammation X Can be caused by trauma, fasting, TPN or abdominal surgery 7 Diagnostic Studies ä Ultrasound of abdomen 1 X not for the obese ä HIDA scan X nuclear medicine ä Cholangiograms X endoscopic X transvenous X intraoperative 8 Post-op Care ä High abdominal incision X respiratory compromise ä T-tube X patients need to know how to empty it X may clamp it prior to removal X caution not dislodged with movements ä NO Morphine X spasms of sphincter of Oddi 9 Post-op Nutrition ä Limited fat in diet X can have rapid transit times ä Potential fat soluble vitamin deficit X A, D, E and K ä Weight loss diet 10 LIVER FAILURE ä Cirrhosis ä Drug toxicity X acetaminophen, anesthetics, HCTZ, chemotherapy ä Infection ä Cancer ä ETOH is single most linked cause 11 LIVER FAILURE S/S ä Don’t show up until 80-90% failed -

Seetha Kazhichal

A STUDY ON SEETHA KAZHICHAL Dissertation submitted to THE TAMILNADU DR. M.G.R MEDICAL UNIVERSITY Chennai-32 For the partial fulfillment of the requirements to the Degree of DOCTOR OF MEDICINE (SIDDHA) (Branch IV - Kuzhanthai Maruthuvam) Department of Kuzhanthai Maruthuvam GOVERNMENT SIDDHA MEDICAL COLLEGE PALAYAMKOTTAI – 627 002. MARCH 2008 CONTENTS Page. No INTRODUCTION 1 AIM AND OBJECTIVES 3 REVIEW OF SIDDHA LITERATURES 5 REVIEW OF MODERN LITERATURES 25 MATERIALS AND METHODS 44 RESULTS AND OBSERVATIONS 46 DISCUSSION 67 SUMMARY 73 CONCLUSION 75 ANNEXURES ¾ PREPARATION AND PROPERTIES OF TRIAL MEDICINE 76 ¾ BIOCHEMICAL ANALYSIS OF TRIAL MEDICINE 81 ¾ ANTI MICROBIAL STUDY OF TRIAL MEDICINE 84 ¾ PHARMACOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF TRIAL MEDICINE 85 ¾ LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS OF SHIGELLA AND ENTAMOEBA HISTOLYTICA 97 ¾ PROFORMA OF CASE SHEET 102 BIBLIOGRAPHY 114 CERTIFICATE Certified that I have gone through the dissertation submitted by ------------------- a student of Final M.D.(s), Branch IV, Kuzhandhai Maruthuvam of this college and the dissertation does not represent or reproduce the dissertation submitted and approved earlier. Place: Palayamkottai Date: Professor and Head of the Department, (PG) Br IV, Kuzhanthai Maruthuvam, Govt. Siddha Medical College, Palayamkottai. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, I thank God for his blessings to complete my dissertation work successfully. My foremost thanks to The Vice Chancellor, The Tamil Nadu Dr.M.G.R.Medical University-Chennai , for giving permission to undertake this dissertation. I contribute my thanks to Dr.M.Thinakaran M.D(s)., The Principal,Govt. Siddha Medical College, Palayamkottai for granting permission and facilities to complete this dissertation. I owe a deep sense of gratitude to Dr.R.Patrayan M.D (s)., The Head of the department , Dr.N.Chandra Mohan M.D (s)., Lecturer, Department of Kuzhanthai Maruthuvam , Govt.Siddha Medical College, Palaymkottai for their encouragements , valuable suggestions and necessary guidance during this study. -

Symptomatic Approach to Gas, Belching and Bloating 21

20 Osteopathic Family Physician (2019) 20 - 25 Osteopathic Family Physician | Volume 11, No. 2 | March/April, 2019 Gennaro, Larsen Symptomatic Approach to Gas, Belching and Bloating 21 Review ARTICLE to escape. This mechanism prevents the stomach from becoming IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME (IBS) Symptomatic Approach to Gas, Belching and Bloating damaged by excessive dilation.2 IBS is abdominal pain or discomfort associated with altered with OMT Treatment Options Many patients with GERD report increased belching. Transient bowel habits. It is the most commonly diagnosed GI disorder lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxation is the major and accounts for about 30% of all GI referrals.7 Criteria for IBS is recurrent abdominal pain at least one day per week in the Carly Gennaro, DO1; Helaine Larsen, DO1 mechanism for both belching and GERD. Recent studies have shown that the number of belches is related to the number of last three months associated with at least two of the following: times someone swallows air. These studies have concluded that 1) association with defecation, 2) change in stool frequency, 1 Good Samaritan Hospital Medical Center, West Islip, NY patients with GERD swallow more air in response to heartburn and 3) change in stool form. Diagnosis should be made using these therefore belch more frequently.3 There is no specific treatment clinical criteria and limited testing. Common symptoms are for belching in GERD patients, so for now, physicians continue to abdominal pain, bloating, alternating diarrhea and constipation, treat GERD with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and histamine-2 and pain relief after defecation. Pain can be present anywhere receptor antagonists with the goal of suppressing heartburn and in the abdomen, but the lower abdomen is the most common KEYWORDS: ABSTRACT: Intestinal gas production is a normal physiologic progress. -

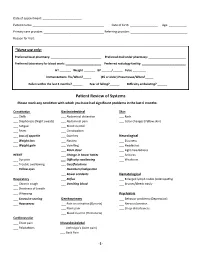

Patient Review of Systems Please Mark Any Condition with Which You Have Had Significant Problems in the Last 6 Months

Date of appointment: ________________________ Patient name: ____________________________________________ Date of birth: _________________ Age: ___________ Primary care provider: _____________________________________ Referring provider: ___________________________________ Reason for Visit: _____________________________________________________________________________________________ *Nurse use only: Preferred local pharmacy: _______________________________ Preferred mail order pharmacy: _______________________ Preferred laboratory for blood work: ______________________ Preferred radiology facility: ___________________________ HT _______ Weight _______ BP ______/______ Pulse ________ Immunizations: Flu/When?_____ (65 or older) Pneumovax/When?_____ Fallen within the last 3 months? ______ Fear of falling?______ Difficulty ambulating? ______ Patient Review of Systems Please mark any condition with which you have had significant problems in the last 6 months: Constitution Gastrointestinal Skin ___ Chills ___ Abdominal distention ___ Rash ___ Diaphoresis (Night sweats) ___ Abdominal pain ___ Color changes (Yellow skin) ___ Fatigue ___ Blood in stool ___ Fever ___ Constipation ___ Loss of appetite ___ Diarrhea Neurological ___ Weight loss ___ Nausea ___ Dizziness ___ Weight gain ___ Vomiting ___ Headaches ___ Black stool ___ Light-headedness HEENT ___ Change in bowel habits ___ Seizures ___ Eye pain ___ Difficulty swallowing ___ Weakness ___ Trouble swallowing ___ Gas/flatulence ___ Yellow eyes ___ Heartburn/indigestion ___ Bowel accidents Hematological -

Reflux Esophagitis

Reflux Esophagitis KEY FACTS TERMINOLOGY • Caustic esophagitis • Inflammation of esophageal mucosa due to PATHOLOGY gastroesophageal (GE) reflux • Lower esophageal sphincter: Decreased tone leads to IMAGING increased reflux • Irregular ulcerated mucosa of distal esophagus • Hydrochloric acid and pepsin: Synergistic effect • Foreshortening of esophagus: Due to muscle spasm CLINICAL ISSUES • Inflammatory esophagogastric polyps: Smooth, ovoid • 15-20% of Americans commonly have heartburn due to elevations reflux; ~ 30% fail to respond to standard-dose medical • Hiatal hernia in > 95% of patients with stricture therapy ○ Probably is result, not cause, of reflux ○ Prevalence of GE reflux disease has increased sharply • Peptic stricture (1- to 4-cm length): Concentric, smooth, with obesity epidemic tapered narrowing of distal esophagus • Symptoms: Heartburn, regurgitation, angina-like pain TOP DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES ○ Dysphagia, odynophagia • Scleroderma • Confirmatory testing: Manometric/ambulatory pH- monitoring techniques • Drug-induced esophagitis ○ Endoscopy, biopsy • Infectious esophagitis Imaging in Gastrointestinal Disorders: Diagnoses • Eosinophilic esophagitis (Left) Graphic shows a small type 1 (sliding) hiatal hernia ſt linked with foreshortening of the esophagus, ulceration of the mucosa, and a tapered stricture of distal esophagus. (Right) Spot film from an esophagram shows a small hiatal hernia with gastric folds ſt extending above the diaphragm. The esophagus appears shortened, presumably due to spasm of its longitudinal muscles. A stricture is present at the gastroesophageal (GE) junction, and persistent collections of barium indicate mucosal ulceration. (Left) Prone film from an esophagram shows a tight stricture ſt just above the GE junction with upstream dilation of the esophagus. The herniated stomach is pulled taut as a result of the foreshortening of the esophagus, a common and important sign of reflux esophagitis.