Guiding Cases Surveys 指导性案例调查 TM Cumulative Analysis of All

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Miraculous Ningguo City of China and Analysis of Influencing Factors of Competitive Advantage

www.ccsenet.org/jgg Journal of Geography and Geology Vol. 3, No. 1; September 2011 A Miraculous Ningguo City of China and Analysis of Influencing Factors of Competitive Advantage Wei Shui Department of Eco-agriculture and Regional Development Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu Sichuan 611130, China & School of Geography and Planning Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510275, China Tel: 86-158-2803-3646 E-mail: [email protected] Received: March 31, 2011 Accepted: April 14, 2011 doi:10.5539/jgg.v3n1p207 Abstract Ningguo City is a remote and small county in Anhui Province, China. It has created “Ningguo Miracle” since 1990s. Its general economic capacity has been ranked #1 (the first) among all the counties or cities in Anhui Province since 2000. In order to analyze the influencing factors of competitive advantages of Ningguo City and explain “Ningguo Miracle”, this article have evaluated, analyzed and classified the general economic competitiveness of 61 counties (cities) in Anhui Province in 2004, by 14 indexes of evaluation index system. The result showed that compared with other counties (cities) in Anhui Province, Ningguo City has more advantages in competition. The competitive advantage of Ningguo City is due to the productivities, the effect of the second industry and industry, and the investment of fixed assets. Then the influencing factors of Ningguo’s competitiveness in terms of productivity were analyzed with authoritative data since 1990 and a log linear regression model was established by stepwise regression method. The results demonstrated that the key influencing factor of Ningguo City’s competitive advantage was the change of industry structure, especially the change of manufacture structure. -

Qingdao Port International Co., Ltd. 青島港國際股份有限公司

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness, and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. Qingdao Port International Co., Ltd. 青 島 港 國 際 股 份 有 限 公 司 (A joint stock company established in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 06198) VOLUNTARY ANNOUNCEMENT UPDATE ON THE PHASE III OF OIL PIPELINE PROJECT This is a voluntary announcement made by Qingdao Port International Co., Ltd. (the “Company”, together with its subsidiaries, the “Group”). Reference is made to the voluntary announcement of the Company dated 28 December 2018, in relation to the groundbreaking ceremony for the phase III of the Dongjiakou Port-Weifang-Central and Northern Shandong oil pipeline construction project (the “Phase III of Oil Pipeline Project”). The Phase III of Oil Pipeline Project was put into trial operation on 8 January 2020. As of the date of this announcement, the Dongjiakou Port-Weifang-Central and Northern Shandong oil pipeline has extended to Dongying City in the north, opening the “Golden Channel” of crude oil industry chain from the Yellow Sea to the Bohai Bay. SUMMARY OF THE PHASE III OF OIL PIPELINE PROJECT The Phase III of Oil Pipeline Project is the key project for the transformation of old and new energy in Shandong Province, and the key construction project of the Group. -

Analysis of the Characteristics in a Strong Convective Weather Process

Analysis of the characteristics in a strong convective weather process in China Li Zuxian Huang Xiaoyu Deng Zhaoping Xu Lin Hunan Meteorological Observatory, Changsha, China, 410007 ABSTRACT Introduction From the mid-70s, through the double Doppler By using the numerical forecasting product, the weather radar observation to understand thunderstorm convention, the automatic weather station and system's internal structure, especially the system Doppler weather radar materials, it analyzed interior's three dimensional wind field (Ray et al.1975), Hunan strong convective weather process on April 4, discovered particularly the hail storms wind field has 2006. The result indicated: The preliminary weather the cyclone type circulation characteristic, the returns to warmer continually, and accumulate ascendant current located at the weak echo region. massive unstable energies, the vertical wind shear, Chisholm and Renick (1972) and Browning(1977) the power, the thermal energy and the water vapor divides into the multi-monomer storm and the super condition are advantageous to the strong convection monomer storm the storm through using the past storm weather production; During this process, ground and research and the recognition of the storm power and the upper air temperature, the humidity, the kinetic the structure of Micro physics ; The storm has four energy perturbation quantity, the ground temperature stages: initial development period, the beginning of perturbation is bigger than each level upper air of echo characteristic, mature stage, dissipation stage. the temperature perturbation obviously, it explained Klemp(1987) reorganizes many year findings, showing that the ground thermal energy function is bigger that the Mesoscale cyclone in the fierce convection than that of the high level; In the disturbance storm is the horizontal direction scroll which cuts by moisture field, transfers the weather to have the the environment vertical wind forms does after the region each level humidity is smaller than the convection development reverse creates. -

Changsha:Gateway to Inland China

0 ︱Changsha: Gateway to Inland China Changsha Gateway to Inland China Changsha Investment Environment Report 2013 0 1 ︱ Changsha: Gateway to Inland China Changsha Changsha is a central link between the coastal areas and inland China ■ Changsha is the capital as well as the economic, political and cultural centre of Hunan province. It is also one of the largest cities in central China(a) ■ Changsha is located at the intersection of three major national high- speed railways: Beijing-Guangzhou railway, Shanghai-Kunming railway (to commence in 2014) and Chongqing-Xiamen railway (scheduled to start construction before 2016) ■ As one of China’s 17 major regional logistics hubs, Changsha offers convenient access to China’s coastal areas; Hong Kong is reachable by a 1.5-hour flight or a 3-hour ride by CRH (China Railways High-speed) Changsha is well connected to inland China and the world economy(b) Domestic trade (total retail Total value of imports and CNY 245.5 billion USD 8.7 billion sales of consumer goods) exports Value of foreign direct Total value of logistics goods CNY 2 trillion, 19.3% investment and y-o-y USD 3.0 billion, 14.4% and y-o-y growth rate growth rate Total number of domestic Number of Fortune 500 79.9 million, 34.7% tourists and y-o-y growth rate companies with direct 49 investment in Changsha Notes: (a) Central China area includes Hunan Province, Hubei Province, Jiangxi Province, Anhui Province, Henan Province and Shanxi Province (b) Figures come from 2012 statistics Sources: Changsha Bureau of Commerce; Changsha 2012 National Economic and Social Development Report © 2013 KPMG Advisory (China) Limited, a wholly foreign owned enterprise in China and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative ("KPMG International"), a Swiss entity. -

Xiaodong.Deng Add : Wenzhou Zhejiang China Partner Tel : 13758802800 Email : [email protected]

Law Firm : Shanghai Landing Law Offices(Wenzhou) Xiaodong.Deng Add : Wenzhou Zhejiang China Partner Tel : 13758802800 Email : [email protected] Settlement on intellectual property rights and unfair competition, civil and commercial dispute Practice Areas Graduated from Zhejiang University on June 30, 2004 (self-taught examination) Education The lawyer Xiaodong Deng focuses on legal services for cultural media, film and television Experiences entertainment, intellectual property protection and civil and commercial dispute settlement. He is good at providing comprehensive legal services for enterprises and has rich practical experience in intellectual property protection and application, civil and commercial disputes. • The case of infringement of the exclusive right to use a registered trademark sued by Osram Achievements Co., LTD. against Dai X; • The case of infringement of the exclusive right to use a registered trademark sued by Honeywell Internataional Inc.against Ruian Wanlicheng Filter Co. LTD; • The case of infringement of the exclusive right to use a registered trademark sued by Bestiu Shoes Co. LTD. against Jiangsu Danyang Kaixin Apple Shoes Co. LTD; • The case of infringement of copyright sued by Guangdong Zhongke Culture Communication Co., LTD. against Hangzhou Trust-Mart, Century Lianhua, Vanguard, Tesco, Ningbo Gabby, Xinyijia, Taizhou Netcom, Taizhou Guoshang, Taizhou Hualian, Jinhuazhongyang, Jinhua Wanshun, etc; • The case of infringement of copyright sued by Ningbo Chenggong Multimedia Communication Co., LTD. against Shaoxing Yimin Network Technology Co., LTD; • The case of infringement of copyright sued by Lin X against Qiaodong Town People's Government of Cangnan County; • The case of infringement of patent sued by Luo X against KWONG CHAK FAT MANUFACTORY LIMITED; • Patent invalidation case of Tong X; • Trademark licensing contract dispute case sued by Lin X against Wenzhou Binxue Clothing Co. -

Originally, the Descendants of Hua Xia Were Not the Descendants of Yan Huang

E-Leader Brno 2019 Originally, the Descendants of Hua Xia were not the Descendants of Yan Huang Soleilmavis Liu, Activist Peacepink, Yantai, Shandong, China Many Chinese people claimed that they are descendants of Yan Huang, while claiming that they are descendants of Hua Xia. (Yan refers to Yan Di, Huang refers to Huang Di and Xia refers to the Xia Dynasty). Are these true or false? We will find out from Shanhaijing ’s records and modern archaeological discoveries. Abstract Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Seas ) records many ancient groups of people in Neolithic China. The five biggest were: Yan Di, Huang Di, Zhuan Xu, Di Jun and Shao Hao. These were not only the names of groups, but also the names of individuals, who were regarded by many groups as common male ancestors. These groups first lived in the Pamirs Plateau, soon gathered in the north of the Tibetan Plateau and west of the Qinghai Lake and learned from each other advanced sciences and technologies, later spread out to other places of China and built their unique ancient cultures during the Neolithic Age. The Yan Di’s offspring spread out to the west of the Taklamakan Desert;The Huang Di’s offspring spread out to the north of the Chishui River, Tianshan Mountains and further northern and northeastern areas;The Di Jun’s and Shao Hao’s offspring spread out to the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River, where the Di Jun’s offspring lived in the west of the Shao Hao’s territories, which were near the sea or in the Shandong Peninsula.Modern archaeological discoveries have revealed the authenticity of Shanhaijing ’s records. -

![Investigation No. 337-TA-1216]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0446/investigation-no-337-ta-1216-420446.webp)

Investigation No. 337-TA-1216]

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 09/03/2020 and available online at federalregister.gov/d/2020-19465, and on govinfo.gov 7020-02 INTERNATIONAL TRADE COMMISSION [Investigation No. 337-TA-1216] Certain Vacuum Insulated Flasks and Components Thereof; Institution of Investigation AGENCY: U.S. International Trade Commission. ACTION: Notice. SUMMARY: Notice is hereby given that a complaint was filed with the U.S. International Trade Commission on July 29, 2020, under section 337 of the Tariff Act of 1930, as amended, on behalf of Steel Technology, LLC d/b/a Hydro Flask of Bend, Oregon and Helen of Troy Limited of El Paso, Texas. A supplement was filed on August 18, 2020. The complaint, as supplemented, alleges violations of section 337 based upon the importation into the United States, the sale for importation, and the sale within the United States after importation of certain vacuum insulated flasks and components thereof by reason of infringement of: (1) the sole claims of U.S. Design Patent No. D806,468 (“the ’468 patent”); U.S. Design Patent No. D786,012 (“the ’012 patent”); U.S. Design Patent No. D799,320 (“the ’320 patent”); and (2) U.S. Trademark Registration No. 4,055,784 (“the ’784 trademark”); U.S. Trademark Registration No. 5,295,365 (“the ’365 trademark”); U.S. Trademark Registration No. 5,176,888 (“the ’888 trademark”); and U.S. Trademark Registration No. 4,806,282 (“the ’282 trademark”). The complaint further alleges that an industry in the United States exists as required by the applicable Federal Statute. -

An Empirical Analysis of Industrialization Development Based on AHP in Shandong Peninsula City Group

2015 2nd International Conference on Material Engineering and Application (ICMEA 2015) ISBN: 978-1-60595-323-6 An Empirical Analysis of Industrialization Development Based on AHP in Shandong Peninsula City Group Ning Liu1, Jinghua Sha & Hongyun Ma2 1School of Humanities and Economic Management, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, China 2Key Laboratory of Carrying Capacity Assesssment for Resource and Environment, Ministry of Land & Resources, Beijing, China ABSTRACT: It is very meaningful to evaluate the degree of industrialization in Shandong Peninsula City Group for internal development of the cities group and the construction of new urbanization in China. This study analyzed the industrialization development of Shandong peninsula city group and every city with the method of AHP. The conclusion indicted that the industrialization stage of Shandong peninsula city group is the advanced stage of industrial implementation phase, while the industrialization stage of Shandong province is the primary stage of industrial implementation phase. Jinan and Qingdao have been after industrialization stage, while Zibo, Dongying, Yantai and Weihai have been the advanced stage of industrial implementation phase, and Weifang and Rizhao have been the primary stage of industrial implementation phase. 1 INTRODUCTION Industrialization is defined to be a process that with the continuous development of modern industry, especially the development of manufacturing, the proportion of industrial value accounted for gross domestic product (GDP) keep increasing, and the industry have developed to be the pillar of the economy. World industrialization originated British industrial revolution in the 18th century. Industrialization process with characteristics of mechanized production changed mode of production and way of life, transferring labor, capital and other factors of production from countryside to city, driving the progress of the society. -

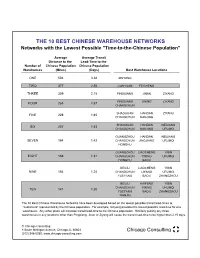

10 BEST CHINESE WAREHOUSE NETWORKS Networks with the Lowest Possible "Time-To-The-Chinese Population"

THE 10 BEST CHINESE WAREHOUSE NETWORKS Networks with the Lowest Possible "Time-to-the-Chinese Population" Average Average Transit Distance to the Lead-Time to the Number of Chinese Population Chinese Population Warehouses (Miles) (Days) Best Warehouse Locations ONE 504 3.38 XINYANG TWO 377 2.55 LIANYUAN FEICHENG THREE 309 2.15 PINGXIANG JINAN ZIYANG PINGXIANG JINING ZIYANG FOUR 265 1.87 CHANGCHUN SHAOGUAN HANDAN ZIYANG FIVE 228 1.65 CHANGCHUN NANJING SHAOGUAN HANDAN NEIJIANG SIX 207 1.53 CHANGCHUN NANJING URUMQI GUANGZHOU HANDAN NEIJIANG SEVEN 184 1.42 CHANGCHUN JINGJIANG URUMQI HONGHU GUANGZHOU LIAOCHENG YIBIN EIGHT 168 1.31 CHANGCHUN YIXING URUMQI HONGHU BAOJI BEILIU LIAOCHENG YIBIN NINE 154 1.24 CHANGCHUN LIYANG URUMQI YUEYANG BAOJI ZHANGZHOU BEILIU KAIFENG YIBIN CHANGCHUN YIXING URUMQI TEN 141 1.20 YUEYANG BAOJI ZHANGZHOU TIANJIN The 10 Best Chinese Warehouse Networks have been developed based on the lowest possible transit lead-times to "customers" represented by the Chinese population. For example, Xinyang provides the lowest possible lead-time for one warehouse. Any other place will increase transit lead-time to the Chinese population. Similarly putting any three warehouses in any locations other than Pingxiang, Jinan or Ziyang will cause the transit lead-time to be higher than 2.15 days. © Chicago Consulting 8 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, IL 60603 Chicago Consulting (312) 346-5080, www.chicago-consulting.com THE 10 BEST CHINESE WAREHOUSE NETWORKS Networks with the Lowest Possible "Time-to-the-Chinese Population" Best One City -

World Bank-Financed Anhui Aged Care

SFG3798 REV Zhongzi Huayu REV RR RREV Public Disclosure Authorized G. H. P. Z. J. Zi No. 1051 World Bank-financed Anhui Aged Care System Demonstration Project Public Disclosure Authorized Environment and Social Management Framework (ESMF) Public Disclosure Authorized Commissioned by: Department of Civil Affairs of Anhui Public Disclosure Authorized Province Prepared by: Beijing Zhongzi Huayu Environmental Protection Technology Co., Ltd. Prepared in: December 2017 Table of Contents I. Introduction and Objectives........................................................................................ 3 II. Project Overview ....................................................................................................... 3 III. Policy Framework of Environmental and Social Problems ..................................... 5 IV. Paths of Solving Environmental and Social Problems ........................................... 11 4.1 The first step: identify sub-projects according to project selection criteria ... 11 4.2 The second step: screen potential environmental and social impacts ............ 11 4.3 The third step: review the screening results ................................................... 13 4.4 The fourth step: prepare the safeguard documents and have public consultation and information disclosure .............................................................. 14 4.5 The fifth step: review and approve the safeguard documents ........................ 15 4.6 The sixth step: implement, supervise, monitor and assess the approved actions -

January 04, 1939 Translation of a Letter from Governor Shicai Sheng to Cdes

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified January 04, 1939 Translation of a Letter from Governor Shicai Sheng to Cdes. Stalin, Molotov, and Voroshilov Citation: “Translation of a Letter from Governor Shicai Sheng to Cdes. Stalin, Molotov, and Voroshilov,” January 04, 1939, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, RGASPI f. 82 op. 2 d. 1238, l. 176-182. Obtained by Jamil Hasanli and translated by Gary Goldberg. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/121890 Summary: Governor Sheng Shicai expresses gratitude to Cdes. Stalin, Molotov, and Voroshilov for the opportunity to visit Moscow. After reporting critical remarks made by Fang Lin against the Soviet Union and the Communist Party, Sheng Shicai requests that the All-Union Communist Party dispatch a politically experienced person to Urumqi to discuss Party training and asks that the Comintern order the Chinese Communist Party in Xinjiang to liquidate the Party organization. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the MacArthur Foundation. Original Language: Russian Contents: English Translation Scan of Original Document Top Secret Copy Nº [left blank] TRANSLATION OF A 4 JANUARY 1939 LETTER OF GOVERNOR SHENG SHICAI TO CDES. STALIN, MOLOTOV, AND VOROSHILOV "Deeply respected Mr. STALIN, Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars MOLOTOV, and Marshal VOROSHILOV! Although a quite long four-month period has passed since I left Moscow, recalling my stay in Moscow, it seems that it was not long ago at all. When my wife and I were in Moscow, you gave us a good reception and devoted much of your valuable time to us. My wife and I were not only grateful to you for this, but were also left with an unforgettable deep impression. -

The Darkest Red Corner Matthew James Brazil

The Darkest Red Corner Chinese Communist Intelligence and Its Place in the Party, 1926-1945 Matthew James Brazil A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Doctor of Philosophy Department of Government and International Relations Business School University of Sydney 17 December 2012 Statement of Originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted previously, either in its entirety or substantially, for a higher degree or qualifications at any other university or institute of higher learning. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources has been acknowledged. Matthew James Brazil i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Before and during this project I met a number of people who, directly or otherwise, encouraged my belief that Chinese Communist intelligence was not too difficult a subject for academic study. Michael Dutton and Scot Tanner provided invaluable direction at the very beginning. James Mulvenon requires special thanks for regular encouragement over the years and generosity with his time, guidance, and library. Richard Corsa, Monte Bullard, Tom Andrukonis, Robert W. Rice, Bill Weinstein, Roderick MacFarquhar, the late Frank Holober, Dave Small, Moray Taylor Smith, David Shambaugh, Steven Wadley, Roger Faligot, Jean Hung and the staff at the Universities Service Centre in Hong Kong, and the kind personnel at the KMT Archives in Taipei are the others who can be named. Three former US diplomats cannot, though their generosity helped my understanding of links between modern PRC intelligence operations and those before 1949.