The Hijab Ban and the Evolution of French Nationalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teacher Resource Packet for Vietnamese Students. INSTITUTION Washington Office of the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, Olympia

)xocliMENTRESUME ,ED 118 679 UD 015 707 TITLE- Teacher Resource Packet for Vietnamese Students. INSTITUTION Washington Office of the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, Olympia. PUB DATE Jul 75 NOTE'-. litp.; This document is available in microfiche only 'due to the print size of parts of the original 0 document EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Asian Americans; Bilingual Education; *Bilingual Students; Educational. Resources; Elementary School Students; English (Second Language); *Ethnic Groups;, Guidelines; Immigrants; *Indo hinese; Minority Group Children; Minority Groups; *Re ugees; Resource Guides; Resource Materials; Se ndary School Students; *Student Characterist cs;- Student Needs; Student Problems; Student TeacheRelationship; Teacher Guidance; Teacher Respons bility IDENTIFIERS *Vietnam r ABSTRACT This packet provides information for classroom , teachers who will be working with Vietnamese students Among the subject matter discussed in the history and general in ormation section are the Republic of Vietnam, family loyalty, p ofessional man, politeness and restraint, village life, fruits and vegetables, meat dishes, festivals, and religion. Other sections include a summary of some cultural differences, a Vietnamese language guide, and Asian immigrant impressions. A section on bilingual education information discus es theory, definition, and the legal situation concerning bilingu4lism and English as a second language. Suggestions for interacting with non-English dominant students in all grade levels in either a regular classroom setting or a secondary school setting are provided. Relevant resources, such as materials that can be used for basic instruction in English (as a second language) classes, reading resources, and community resources are enclosed. (Author/AM) **********L********************************************************* Documents acquired by ERIlinclude many informal unpublished * materials not aotailable from ther sources. -

Human Rights of Women Wearing the Veil in Western Europe

Human Rights of Women Wearing the Veil in Western Europe Research Paper I. Introduction The present paper analyses legislation, policies, and case-law surrounding religious attire in a number of countries in Western Europe and how they affect the human rights of women and girls who wear the veil in Western Europe. It also more broadly analyses discrimination and violence experienced by women wearing the veil in Europe learning from their own voice. Throughout the paper, the terminology ‘veil’ is used to refer to a variety of religious attire worn mostly, but not exclusively, by Muslim women. There are different types of clothing that cover the body. This research is focused on manifestations of veils that are the subject of regulation in several Western European Countries. They include the hijab (a piece of clothing that covers the head and neck, but not the face), niqab (a piece of clothing that covers the face, where only the eyes are visible), burqa (a piece of clothing that covers both the face and eyes), jilbab (a loose piece of clothing that covers the body from head to toe), or abaya, kaftan, kebaya (a loose, often black, full body cover overcoat). The head and body covers are often combined. In several countries, some of these clothing are based on traditional costumes rather than religion and are often worn by rural communities in the countries of origins. The paper also uses the terminology ‘full-face veil’ or ‘face-covering veil’ to refer to both niqab and burqa. Furthermore, it refers to burkini, a swimsuit that covers the body from head to ankles, completed by a dress. -

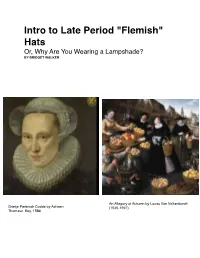

"Flemish" Hats Or, Why Are You Wearing a Lampshade? by BRIDGET WALKER

Intro to Late Period "Flemish" Hats Or, Why Are You Wearing a Lampshade? BY BRIDGET WALKER An Allegory of Autumn by Lucas Van Valkenborch Grietje Pietersdr Codde by Adriaen (1535-1597) Thomasz. Key, 1586 Where Are We Again? This is the coast of modern day Belgium and The Netherlands, with the east coast of England included for scale. According to Fynes Moryson, an Englishman traveling through the area in the 1590s, the cities of Bruges and Ghent are in Flanders, the city of Antwerp belongs to the Dutchy of the Brabant, and the city of Amsterdam is in South Holland. However, he explains, Ghent and Bruges were the major trading centers in the early 1500s. Consequently, foreigners often refer to the entire area as "Flemish". Antwerp is approximately fifty miles from Bruges and a hundred miles from Amsterdam. Hairstyles The Cook by PieterAertsen, 1559 Market Scene by Pieter Aertsen Upper class women rarely have their portraits painted without their headdresses. Luckily, Antwerp's many genre paintings can give us a clue. The hair is put up in what is most likely a form of hair taping. In the example on the left, the braids might be simply wrapped around the head. However, the woman on the right has her braids too far back for that. They must be sewn or pinned on. The hair at the front is occasionally padded in rolls out over the temples, but is much more likely to remain close to the head. At the end of the 1600s, when the French and English often dressed the hair over the forehead, the ladies of the Netherlands continued to pull their hair back smoothly. -

Mantilla Veil NHV Winners and More

Issue 113 - August 2015 This month... Next Issue: August 19th, 2015 Marketing Hats Caren Lee Make a Mantilla Veil NHV Winners And More... the e-magazine for those who make hats Issue 113 August 2015 Contents: The Hatwalk 2 SJ Brown’s advice for marketing millinery on fashion weeks’ runways. Hat of the Month 6 A Melbourne Cup piece by Caren Lee. Make a Shoulder Length Mantilla Veil 8 A tutorial by Denise Innes-Spencer of The British School of Millinery. The NHV Hat Contest 19 The Dutch Hat Association’s 2015 competition winners. Letter to the Editor 24 Advice on applying stiffener. The Back Page 25 Royal Ascot 2015, HATalk Give Away and how to contact us. Cover/Back Pages: 1 www.hatalk.com Head wear by Denise Innes The Hatwalk: Marketing millinery on fashion weeks’ runways Not every country can boast a ‘Hat handing out thousands of business Week’ like England. As a milliner in cards. Still, I was getting nowhere. the United States, I wish there was a So, how does a milliner sell hats New York Hat Week or Chicago Hat in a country where hats are not so Week, but no such luck. Until those commonplace? As with any good cities take the cue from London and marketing plan, you have to know create their own Hat Weeks, I will be your audience. perfectly content just crashing the party on my local runway. After trying all the normal marketing ploys, I realized the normal American Why am I crashing the ‘fashion week’ woman is not my target audience. -

December 18, 1953

Temple !3 e tl1,-El 6S8 Bro~d St . R. :L~.--------. Rhode lslond's Only Anglo-Jewish Greotest Newspoper Independent In Weekly The JewisffHl'fiJa Rhode Island VOL. XXXVIIl, No. 42 FRIDAY, DECEMBER 18, 1913 PROVIDENCE, R. I TWELVE PAGES 10 CENTS THE COPY Prevention, Control of Family l'roblems to , Be Study Project Technion Starts Capital NEW YORK-Three. American of St. Paul and the Rosenberg communities. each typical of its Foundation of San Francisco. The $100,000 Fund Campaign type, but widely separated as to three new projects will be under geographic location, population, way by January, 1954, and will history and pe-rsonality, have been help check findings concerning selected by the Community Re social problem patterns which Fain, Weisberg search Associates, Inc., to test and were uncovered in the Community demonstrate methods of preven Research Associates' original St. tion and control of family prob Paul study. To Head Drive lems in a new million dollar, four Out of the original study by year project. Community. Research Associates Joseph W. Wunsch, national From East to West. the three are came the startling fact that about president of the American Tech~ Hagerstown, Md., with a popUla six per cent of the population were nton Society, announced today tion of 70.000 and a great h istori absorbing well over half of all that Irving Jay Fain and Mark cal tradition; Winona, Minn., health and welfare funds, both Weisberg have accepted the co typical mid-western town with a public and voluntary. ch airmanship of the Southern New population cf 40,000; and San England Chapter of the American Mateo, Cal., comparatively new Multi-Problem Patterns Technion Society's Capital Fund and fast - growing metropolitan Further, it disclosed that more Campaign. -

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts Shahnaz Begum Laghari PhD University of York Women’s Studies March 2016 Abstract The aim of this project is to investigate the phenomenon of honour-related violence, the most extreme form of which is honour killing. The research was conducted in Sindh (one of the four provinces of Pakistan). The main research question is, ‘Are these killings for honour?’ This study was inspired by a need to investigate whether the practice of honour killing in Sindh is still guided by the norm of honour or whether other elements have come to the fore. It is comprised of the experiences of those involved in honour killings through informal, semi- structured, open-ended, in-depth interviews, conducted under the framework of the qualitative method. The aim of my thesis is to apply a feminist perspective in interpreting the data to explore the tradition of honour killing and to let the versions of the affected people be heard. In my research, the women who are accused as karis, having very little redress, are uncertain about their lives; they speak and reveal the motives behind the allegations and killings in the name of honour. The male killers, whom I met inside and outside the jails, justify their act of killing in the name of honour, culture, tradition and religion. Drawing upon interviews with thirteen women and thirteen men, I explore and interpret the data to reveal their childhood, educational, financial and social conditions and the impacts of these on their lives, thoughts and actions. -

Book Reviews

150 Book Reviews le montre l’étude des dynasties lilloises du négoce étudiées par Jean-Pierre Hirsch (Les Deux Rêves du commerce [Paris : Éditions de l’École des hautes études en sciences sociales, 1992]), le partage égalitaire peut être contourné grâce aux différentes modalités du contrat de mariage à la dispositions des familles, lesquelles utilisent celles qui les arrangent de manière à conserver l’entreprise dans le lignage, quoi qu’il puisse arriver au couple et quel que soit le nombre des enfants nés du mariage. Plus près de nous, les lois et décrets facilitant les donations en France ont profondément bouleversé les transferts de ressource entre les générations, parfois au point que les dons entre vifs ont atteint en vo- lume monétaire celui de l’héritage. Plus encore, si l’on ajoute la défiscalisation des dons entre vifs à la hausse de la masse successorale qui peut être transmise sans être soumise à impôt, on a, dans la France contemporaine, une abolition de fait de l’imposition successorale pour une grande partie de la population, à l’exception des fractions les plus riches du dernier décile. On doit donc prêter attention aussi au fait que l’héritage prend place dans un complexe de disposi- tifs qui s’entremêlent, se chevauchent, s’appuient mutuellement les uns sur les autres, dans les pratiques effectives sinon dans les rhétoriques de légitimation. Finalement, ce travail me semble ouvrir la voie à une approche nouvelle et suggestive en matière d’étude des dispositifs de transferts de ressources. Beckert a centré sa recherche sur la comparaison d’un même dispositif mis en place dans trois pays, mais il est loisible de modifier, puis de complexifier le travail comparatif de la manière suivante. -

Hat, Cap, Hood, Mitre

CHAPTER 1 Headgear: Hat, Cap, Hood, Mitre Introduction down over his shoulders;4 and in Troilus and Criseyde Pandarus urges his niece, a sedate young widow, to Throughout the later Middle Ages (the twelfth to early cast off her face-framing barbe, put down her book and sixteenth centuries), if we are to believe the evidence of dance.5 art, some kind of headgear was worn by both sexes in- In art of the middle medieval period (from about doors and out: at dinner, in church, even in bed. This is the eighth to the eleventh centuries), headgear is less understandable if we consider the lack of efficient heat- well attested. Men are usually depicted bareheaded. ing in medieval buildings, but headgear was much more Women’s heads and necks are wrapped in voluminous than a practical item of dress. It was an immediate mark- coverings, usually depicted as white, so possibly linen is er of role and status. In art, it is possible to distinguish being represented in most cases. There is no clue to the immediately the head of a man from that of woman, as shape of the piece of cloth that makes up this headdress, for example in a fourteenth-century glass panel with a sa- how it is fastened, or whether there is some kind of cap tirical depiction of a winged serpent which has the head beneath it to which it is secured. Occasionally a fillet is of a bishop, in a mitre, and a female head, in barbe* and worn over, and more rarely under, this veil or wimple. -

Honour, Head-Coverings and Headship: 1 Corinthians 11.2-16 in Its Social Context

JSNT 33.1 (2010): 31-58 © The Author(s) 2010 Reprints and Permissions: http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav http://JSNT.sagepub.com DOI: 10.1177/0142064X10376002 Honour, Head-coverings and Headship: 1 Corinthians 11.2-16 in its Social Context Mark Finney Department of Biblical Studies, University of Sheffield, 45 Victoria St, Sheffield S3 7QB, UK m.t.finney@sheffield.ac.uk Abstract A significant yet missing dimension of scholarly engagement with 1 Cor. 11.2-16 is the consideration of honour-shame and its critical importance in ancient cultures. As this section of Paul’s letter abounds in honour-shame terminology, analysis of the text within such a framework will allow a profitable exploration of the reasons why the Corinthians are changing their attire (for purposes of this paper, their head- coverings), in a way that appears to be contrary to what may be considered the Pauline norm. The argument offered here is that notions of honour come to the fore and higher-status male Corinthians are employing modes of head attire to maintain distinctions of status. At the same time, Paul insists upon female head-coverings to safeguard the honour of the community within a context of the potential presence of non-believers in a communal service of worship. Keywords Honour, shame, head-coverings, elite(s), authority Introduction1 The consensual view of this section of Paul’s letter is that it is so enigmatic that its original meaning may be beyond recovery, and this has led 1. For reasons of space this section will deal only with the issue of veils/head- coverings and not hair styles/hair length. -

Rapport Au President De La Republique

COMMISSION DE REFLEXION SUR L’APPLICATION DU PRINCIPE DE LAÏCITE DANS LA REPUBLIQUE RAPPORT AU PRESIDENT DE LA REPUBLIQUE Remis le 11 décembre 2003 1 LETTRE DE MISSION 3 juillet 2003 Monsieur le Président, Je vous remercie d’avoir accepté de présider à la Commission indépendante que j’ai décidé de mettre en place pour mener la réflexion sur l’application du principe de laïcité dans la République. La France est une République laïque. Cette règle solennellement affirmée par notre Constitution est le fruit d’une longue tradition historique. Elle s’est imposée comme une garantie de neutralité des pouvoirs publics et de respect des croyances. Elle s’est profondément enracinée dans nos institutions avec la loi du 9 décembre 1905, qui a séparé les Eglises de l’Etat. Cette grande loi républicaine a su s’adapter aux évolutions de la société française depuis un siècle en respectant les particularités de chaque religion. Elle recueille l’adhésion de toutes les confessions religieuses et de tous les courants de pensée, qui y voient la meilleure défense de la liberté de croire ou de ne pas croire. Cependant, l’application du principe de laïcité fait aujourd’hui l’objet d’interrogations. Sa mise en œuvre dans le monde du travail, dans les services publics, et notamment à l’école, se heurte à des difficultés nouvelles. La République est composée de citoyens ; elle ne peut être segmentée en communautés. Devant le risque d’une dérive vers le communautarisme, plusieurs initiatives ont été prises, comme la création d’une mission d’information parlementaire sur les signes religieux ou le dépôt de propositions de lois relatives à la laïcité. -

Unveiling the Veil: Debunking the Stereotypes of Muslim Women Jennifer Sands Rollins College, [email protected]

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses Summer 2014 Unveiling the Veil: Debunking the Stereotypes of Muslim Women Jennifer Sands Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Sands, Jennifer, "Unveiling the Veil: Debunking the Stereotypes of Muslim Women" (2014). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 60. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/60 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Unveiling the Veil: Debunking the Stereotypes of Muslim Women A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Liberal Studies by Jennifer C. Sands August, 2014 Mentor: Dr. Rachel Newcomb Reader: Dr. Kathryn Norsworthy Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Masters of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Chapter I: Introduction 5 Chapter II: Origins of the Veil 12 Chapter III: Religious Justifications 24 Chapter IV: Misconceptions of Muslim Women 34 Chapter V: Muslim Women of Central Florida 49 Works Referenced 64 3 Acknowledgements It is difficult to express in words the sincere gratitude I feel for all who have helped guide me on my journey through the Masters of Liberal Studies at Rollins College. I have nothing but the highest regard for all who have contributed to my success. First and foremost, I must say an enormous thank you to my amazing thesis advisors. -

To Veil Or Not to Veil: Voices of Malaysian Muslim Women

Intercultural Communication Studies XXII: 2 (2013) Sandra HOCHEL To Veil or Not to Veil: Voices of Malaysian Muslim Women Sandra HOCHEL University of South Carolina Aiken, USA Abstract: Few cultural artifacts exemplify the power of nonverbal communication more than the veil worn by some Muslim women. Rarely has a piece of clothing held such disparate and controversial meanings around the globe. This ethnographic study explores the meanings that some veiled, unveiled, and sometimes-veiled Muslim women in one state in Malaysia assign to this head covering by examining the reasons for their veiling decisions. Results illustrate that meanings are complex and individually assigned and that one cannot gauge religious beliefs or devotion solely on dress. The findings also demonstrate the power of this nonverbal artifact to influence self-image and behavior. Many of the results of this study are congruent with previous research on the meanings of the veil to Muslim women in other parts of the globe, but some are incongruent, emphasizing that meanings are both culturally and contextually dependent. Keywords: Veil, Nonverbal Communication, Malaysian Muslim Women, Religious Clothing, Tudung 1. Introduction Over the last few decades, a piece of fabric has become a powerful and divisive symbol worldwide. The veil as worn by some Muslim women has assumed iconic proportions around the globe. To some it symbolizes piety; to others, oppression. To some it is a rejection of Western morality; to others, a rejection of modernity. To some, it is a religious statement supporting Islam as a way of living; to others, a political statement supporting violent Islamists.