Erkki Melartin's Symphony No. 2, E Minor (Opus 30, No. 2)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TOCC0416DIGIBKLT.Pdf

ERKKI MELARTIN Songs to Swedish Texts Four Runeberg Settings 1 Mellan friska blomster (‘Among budding fowers’), Op. 172, No. 2 (1931?) 0:48 2 Flickans klagan (‘The Girl's Lament’), Op. 14, No. 1 (1901)* 2:16 3 Törnet (‘The Thornèd Rose’), Op. 170, No. 3 (1931) 1:36 Hedvig Paulig, soprano 4 Stum kärlek (‘Silent Love’), Op. 116, No. 5 (1919) 2:21 Ilmo Ranta, piano Jan Söderblom, violin 10 – 13 , 22 Five Hemmer Settings 5 Mitt hjärta behöver… (‘My heart requires…’), Op. 116, No. 6 (1919) 2:30 6 Under häggarna (‘Under the Bird-Cherry Trees’), Op. 86, No. 3 (1914) 1:44 7 Bön om ro (‘Prayer for Rest’), Op. 122, No. 6 (1924) 2:03 8 Elegie (‘Elegy‘), Op. 96, No. 1 (1916) 2:56 9 Akvarell (‘Watercolour‘), Op. 96, No. 2 (1916) 1:56 Tagoresånger (‘Tagore Songs’), Op. 105 11:54 10 No. 1 Skyar (‘Clouds’) (1914) 3:20 11 No. 2 Sagan om vårt hjärta (‘The Tale of our Heart’) (1918) 2:24 12 No. 3 Smärtan (‘The Pain’) (1918)** 2:53 13 No. 4 Allvarsdagen (‘On the Last Day’) (1914) 3:17 Other Swedish Settings 14 Skåda, skåda hur det våras (‘See, see how the spring appears’), Op. 117, No. 2 (Löwenhjelm; 1921)* 1:57 15 I skäraste morgongryning (‘As aurora broke’), Op. 21, No. 2 (Tavaststjerna; 1896) 3:20 16 Marias vaggsång (‘Mary’s Lullaby’), Op. 3, No. 1 (Levertin; 1897)*** 3:24 17 Maria, Guds moder (‘Mary, Mother of God’), Op. 151, No. 2 (R. Ekelund; 1928) 3:13 18 Stjärnor (‘Stars’), Op. -

Sasha Mäkilä Conducting Madetoja Discoveries About the Art and Profession of Conducting

Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre Sasha Mäkilä Conducting Madetoja Discoveries About the Art and Profession of Conducting A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music) Supervisor: Prof. Mart Humal Tallinn 2018 ABSTRACT Conducting Madetoja. Discoveries About the Art and Profession of Conducting For the material of my doctoral project, I have chosen the three symphonies of the Finnish composer Leevi Madetoja (1887–1947), all of which I have performed in my doctoral concerts during years 2012–2017. In my doctoral thesis, I concentrate on his first symphony, Op. 29, but to fully understand the context it would be beneficial to familiarize oneself with my doctoral concerts on the accompanying DVDs, as well as with the available commercial and archival recordings of Madetoja’s three symphonies. The aim of this thesis is to understand the effect of scholarly activity (in this case working with manuscripts and recordings) on the artistic and practical aspects of a conductor’s work; this is not a study on the music of Madetoja per se, but I am using these hitherto unknown symphonies as a case study for my research inquiries. My main research inquiry could be formulated as: What kind of added value the study of composer’s manuscripts and other contemporary sources, the analysis of the existing recordings of the work by other performers, and the experience gained during repeated performances of the work, bring to performing (conducting) the work, as opposed to working straightforwardly using only the readily available published edition(s)? My methods are the analysis of musical scores, manuscripts and recordings, critical reflection on my own artistic practices, and two semi-structured interviews with conductor colleagues. -

Symphony No. 4 in E Major Op. 80 by Erkki Melartin

Symphony No. 4 in E Major Op. 80 by Erkki Melartin The five first of the six symphonies by Erkki Melartin (1875–1937), dated from 1903 to 1916, represent the National Romantic Finnish musical heritage based on Austro-German sym- phonic tradition. Back in Melartin’s time, their premieres became substantial, patriotic events, as was the case with the type of national symphony concerts introduced by Jean Sibelius . Typical for these concerts was the immediate presence of the composer. Accord- ingly, Melartin conducted all the premieres of his symphonies himself. After the occasions he always was greatly applauded and celebrated with great floral tributes. In addition, the crit- ics of the time gave great acknowledgement to Melartin’s symphonies. Melartin considered himself primarily as a composer, although he also was a professional conductor, a professor of music theory and composition, and from 1911 on he also worked as the director of the Helsinki Conservatory – later the Sibelius Academy – for 25 years. In his large oeuvre, e.g. the symphonies and the opera Aino are significant works when considering their artistic importance, but were left in oblivion after the composer’s death and during post-war Modernism. Since Melartin’s large-scale works were left unpublished during the composer´s lifetime – apart from Symphony No. 6 –, there has been an unnecessarily high threshold for bringing up or getting acquainted with them. In 2006, the Erkki Melartin Society launched an editing and clean-copying project for Melar- tin’s symphonies. The aim was to promote their performing, and help them become a living part of the music culture in Finland. -

Per Speculum in Enigmatae 6 Klavierstücke / Six Pieces for Piano

Erkki Melartin Per speculum in enigmatae 6 Klavierstücke / Six pieces for piano Op. 93 PIANO I Katedralen 1 II Die andere Seite 4 III Dunkle Träume 6 IV Schwester Namenlos 8 V Souvenir 9 VI Weichnactsglocken 11 KL 78.61 ISMN 979-0-55011-630-6 Copyright © Fennica Gehrman Oy, Helsinki Music typeset by Jani Kyllönen Translation Susan Sinisalo Printed in the EU. POD 2020. Erkki Melartinin pianosarja Per speculum in enigmatae, op. 93 Erkki Melartin oli 1910-luvun alussa Suomen keskeisiä säveltäjiä, jonka uudet, opusnume- roidut pianoteokset julkaistiin lähes rutiininomaisesti. Poikkeuksen muodostaa kuusiosai- nen sarja Per speculum in enigmatae op. 93, joka julkaistaan ensimmäisen kerran vasta nyt, yli 100 vuotta syntymänsä jälkeen. Syytä sarjan torjumiseen kustantamossa ei tiedetä. Sä- veltäjällä itsellään on selvästi ollut vaikeuksia kokonaisuuden hahmottamisessa, sillä hän numeroi sarjan kolmeen kertaan. Varhaisissa luonnoksissa on opusnumero 78, kustanta- jalle menneissä 87 ja lopulta omaan teosluetteloonsa Melartin kirjasi sen numerolla 93. Nimellä Souvenir ja opusnumerolla 87, nro 5 vuonna 1945 kokoelmassa Finlandia V jul- kaistun viidennen osan käsikirjoitus on joutunut erilleen muista. Käsikirjoitusten vähien päiväysten mukaan Melartin sävelsi osia ainakin vuosina 1912–1913, mutta tarkempaa ko- konaisuuden valmistumisaikaa ei tiedetä. Melartin sovitti sarjan ensimmäisen ja kuuden- nen osan orkesterille osiksi Lyyrilliseen sarjaan III, EM144 (Impressions de Belgique), jonka ensiesitys oli tammikuussa 1916. Pianosarjaa ei tiettävästi esitetty Melartinin elinaikana, vaan Niklas Pokki kantaesitti sen Mäntän musiikkijuhlilla 4.8.2017. Sarjan latinankielinen otsikko on suomeksi suunnilleen ”Peilin kautta näemme arvoituk- sen”. Raamatun korinttolaiskirjeistä peräisin oleva ilmaisu on saksaksi käännettynä Wie in einem Spiegel, jota myös Melartin joissain yhteyksissä käytti. Ensimmäinen osa Katedralen (Tuomiokirkko) on mahdollisesti Brüggen arkkitehtuurin innoittama. -

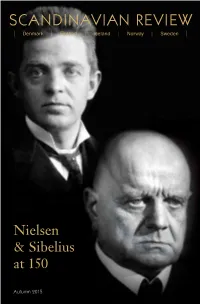

Scandinavian Review Nielsen and Sibelius at 150 Autumn—2015

SCANDINAVIAN REVIEW | Denmark | Finland | Iceland | Norway | Sweden | Nielsen & Sibelius at 150 Autumn 2015 Carl Nielsen Together with Norway’s Jean Sibelius Edvard Grieg, Carl Nielsen and Jean Sibelius are the foremost composers the Nordic countries have ever produced. The two are very different, but they at least share the same year of birth— 1865. NNielsenielsen andand SSibeliusibelius atat 150150 By Daniel M. Grimley YC N M NGER, NGER, A R G RTI / O IELSEN MUSEU GLI A N RL A HE C T PHOTO: 6 SCANDINAVIAN REVIEW AUTUMN 2015 / A. D DE AGOSTINI AUTUMN 2015 SCANDINAVIAN REVIEW 7 Both Nielsen (above) and Sibelius excelled in the field of large-scale orchestral music, but Sibelius (above) and Nielsen first met as students in Berlin in the early 1890s, and remained were equally adept in other genres. friends and colleagues for much of their professional careers. HERE ARE MANY REASONS TO ADMIRE THE LIVES AND WORKS Their strikingly divergent responses to this musical challenge, however, point of the two great Nordic composers, Jean Sibelius and Carl Nielsen, not only to profound differences of political context and cultural geography, Twell beyond celebrating the historical coincidence of their anniversary but also to their respective characters and temperaments. Casting even a year. Few composers can evoke an equivalent sense of time and place with cursory glance at the music of Sibelius and Nielsen is to acknowledge their such vivid intensity. It is difficult to name comparable figures that have been role in a remarkable wave of artistic and intellectual talent in the Nordic so intimately bound up with the formation and promotion of their countries’ region—the “breakthrough” decades of Munch, Strindberg, Gallen-Kallela, musical identities, even if both Nielsen and Sibelius struggled at times with Schjerfbeck, Lagerlöf, Bohr, and others—and to signal their essential impor- the burden that the role of “national composer” inevitably imposed. -

The Harold E. Johnson Jean Sibelius Collection at Butler University

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Special Collections Bibliographies University Special Collections 1993 The aH rold E. Johnson Jean Sibelius Collection at Butler University: A Complete Catalogue (1993) Gisela S. Terrell Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/scbib Part of the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Terrell, Gisela S., "The aH rold E. Johnson Jean Sibelius Collection at Butler University: A Complete Catalogue (1993)" (1993). Special Collections Bibliographies. Book 1. http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/scbib/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Special Collections at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Collections Bibliographies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ^ IT fui;^ JE^ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis IViembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/haroldejohnsonjeOOgise The Harold E. Johnson Jean Sibelius Collection at Butler University A Complete Catalogue Gisela Schliiter Terrell 1993 Rare Books & Special Collections Irwin Library Butler University Indianapolis, Indiana oo Printed on acid-free paper Produced by Butler University Publications ©1993 Butler University 500 copies printed $15.00 cover charge Rare Books & Special Collections Irwin Library, Butler University 4600 Sunset Avenue Indianapolis, Indiana 46208 317/283-9265 Dedicated to Harold E. Johnson (1915-1985) and Friends of Music Everywhere Harold Edgar Johnson on syntynyt Kew Gardensissa, New Yorkissa vuonna 1915. Hart on opiskellut Comell-yliopistossa (B.A. 1938, M.A. 1939) javaitellyt tohtoriksi Pariisin ylopistossa vuonna 1952. Han on toiminut musiikkikirjaston- hoitajana seka New Yorkin kaupungin kirhastossa etta Kongressin kirjastossa, Oberlin Collegessa seka viimeksi Butler-yliopistossa, jossa han toimii musiikkiopin apulaisprofessorina. -

SPRING 2017 Signature Events for Finland 100

Finlandia Foundation® National Our Mission is to sustain both Finnish-American culture in the U.S. and the ancestral tie with Finland by raising funds for grants and scholarships, initiating innovative national programs, and networking with local chapters. SPRING 2017 Signature Events for Finland 100 n tribute to Finland’s Declaration of Independence Finland 100 Signature Events taking place in 2017: Ia century ago, Finlandia Foundation National September 18 Santa Fe, New Mexico: Finland’s is hosting several former President Finland 100 Signature Tarja Halonen will Events throughout participate as a 2017. guest of the Women’s The first of these took International Study place in Florida on Center (WISC). February 18 in the September 22-23 Lake Worth/West Minneapolis: An all- Palm Beach area, Finnish concert by the with FFN as a major Minnesota Orchestra sponsor of the Finland under the baton of 100 Gala at the Delray Music Director Osmo Beach Marriott. A Vänskä. delegation from the Finnish Parliament, November 4 Seattle: led by Speaker Maria Finland 100 concert Lohela, graciously Dignitaries at the February 18 Finland 100 Gala include (far left) Consul by the Northwestern attended the event. General of New York Manu Virtamo; (center) Florida’s Honorary Consul Symphony Orchestra. Peter Makila; and Finnish Parliament Speaker Maria Lohela (in blue he Gala was gown). Photo by Rodney Paavola November 9 New one of several York City: FFN is a T Ossi Rahkonen (below, left) and Consul General Manu Virtamo visit at activities that sponsor of the Finland the Chamber luncheon. Photo by Timo Vainionpaa, usasuomeksi.com weekend, including Centennial Forum the Finnish American at the Union Club, Chamber of Commerce with Keynote Speaker luncheon; Speaker President Martti Lohela addressed the Ahtisaari. -

Erkki Melartin (1875-1937) the SOLO PIANO WORKS MARIA LETTBERG

CLASSICS Erkki Melartin (1875-1937) THE SOLO PIANO WORKS MARIA LETTBERG CD 1 1-6 Lastuja I, Op. 7, Kuusi pianokappaletta / Späne I, Op. 7, Sechs Klavierstücke Chips I, Op. 7, Six Pieces for Piano 7 Legend II, Op. 12 / Die Legende II, Op.12 / The Legend II, Op. 12 8-12 Surullinen puutarha, Op. 52 / Der traurige Garten, Op. 52 The Melancholy Garden, Op. 52 13-17 Lyyrisiä pianokappaleita, Op. 59 / Lyrisches, Op. 59 / Lyric Pieces for Piano, Op.59 18-23 Den hemlighetsfulla skogen, Op. 118, Sex pianostycken Der geheimnisvolle Wald, Op. 118, Sechs Klavierstücke The Mysterious Forest, Op. 118, Six Pieces for Piano 24-29 Sex pianostycken, Op. 123 / Sechs Klavierstücke, Op. 123 Six Pieces for Piano, Op. 123 CD 2 1-24 24 Preludier, Op. 85 / 24 Präludien, Op. 85 / 24 Preludes, Op. 85 25-29 Noli me tangere, Op. 87, Stämningsbilder / Stimmungsbilder / Impressions 30 Legend I, Op. 6 / Die Legende I, Op.6 / The Legend I, Op. 6 2-CD-Set: N 67 048 31 Sonata I, Op. 111, Fantasia apocaliptica per il pianoforte Jewelcase mit Banderole MARIA LETTBERG, Klavier / piano 4 0 4 9 7 7 4 6 7 0 4 8 0 WG: 10 PIANO RARITIES · ERKKI MELARTIN THE SOLO PIANO WORKS Lastuja I, Op. 7 · The Legend II, Op. 12 · The Melancholy Garden, Op. 52 The Mysterious Forest, Op. 118 · 24 Preludes Op. 85 · Fantasia apocaliptica Maria Lettberg The Finnish Composer Erkki before his death he stood up Melartin was a captivating and tern Finland. Later, in the Second Melartin and his Piano Works quietly, in secret, and locked the multi-talented person. -

Finland's Nature, Arts and Independence

Finland’s Nature, Arts and Independence Finns have relied on the nature to keep them warm, nourished and clothed throughout the ancient history. The land has provided clean water, crops, fish and game, and materials for transportation and housing. The harsh climate has required survival skills and sisu, but it has also provided natural beauty that has created inspiration and works of art in a number of disciplines. Late 1800’s brought forward the Finnish identity in language, music, poetry, architecture and design. It continued to strengthen and was presented in various fields of life. The Finnish proverb ‘We are not Swedish, we will not become Russian, so let’s be Finnish’ describes well the commitment of the people. Kalevala, Elias Lönnrot’s work of epic poetry of Karelian and Finnish folklore and mythology brings the early poems, songs, music and pictorial art together. The life was straightforward and simple, because it was efficient and it helped the people survive in the challenging environment. Finland became an autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland in 1809 after the Swedish armies minus the Finnish solders had retreated across the Ahvenanmeri (Åland Sea) and Tornionjoki (Tornio River) and Russia became the new ruler. The idea of independence had started to develop toward the end of the period when Finland was part of the Swedish Empire, but got to a faster pace under the rule of the Russian Tsars, or rather their governor generals. In the mid-1800’s the Central European romanticism reached Finland and the German composer Fredrik Pacius, the Father of Finnish music, came with it, liked Finland and stayed. -

Erkki Melartin

SCORE LIBRARY Erkki Melartin SYMPHONY NO. 3 op. 40 (1906–1907) STUDY SCORE Erkki Melartin SYMPHONY NO. 3 in F Major Op. 40 (1906–1907) Durata: 35 min. 2 Flöten (auch 2 Kleine Flöten) 2 Oboen (2. Oboe auch Englisch Horn) 2 Klarinetten in B 2 Fagotte 4 Hörner in F 3 Trompeten in F 3 Posaunen Bass Tuba Pauken Glockenspiel Triangel Tamburin Kleine Trommel Becken Große Trommel Tam tam Harfe Violinen I Violinen II Bratschen Violoncelli Kontrabässe ISMN 979-0-55011-134-9 (study score) KL 78.541 Copyright © Fennica Gehrman Oy, Helsinki Printed in Helsinki www.fennicagehrman.fi Erkki Melartinin 3. sinfonia, F-duuri (op. 40) Säveltäjä Erkki Melartinin (1875–1937) kuudesta sinfoniasta viisi ensimmäistä vuosilta 1903–1916 edustavat saksalaiseen orkesteritraditioon nojautuvaa, kansallisromanttista suomalaista sävellysperin- nettä. Aikoinaan niiden kantaesitykset muodostuivat suuriksi isänmaallisiksi juhlatilaisuuksiksi Jean Sibeliuksen myötä syntyneen kansallisen sinfoniakonsertin lajityypin mukaisesti. Tunnusmerkillistä näissä konserteissa oli säveltäjän välitön läsnäolo. Myös Melartin johti itse kaikkien sinfonioidensa ensiesitykset ja hän sai helsinkiläisyleisöltä poikkeuksetta suuret suosionosoitukset ja ylenpalttiset kukkatervehdykset. Myös ajankohdan musiikkikriitikot antoivat Melartinin sinfonioille suurta tun- nustusta. Melartin tunsi olevansa kutsumukseltaan ensisijaisesti säveltäjä, vaikka hän toimi myös ammattimai- sena kapellimestarina, musiikinteorian ja sävellyksen opettajana sekä vuo-desta 1911 alkaen 25 vuo- den ajan nykyiseksi Sibelius-Akatemiaksi kehittyneen konser-vatorion johtajana. Melartinin laajassa tuotannossa hänen sinfoniansa ja oopperansa Aino ovat taiteelliselta painoarvoltaan merkittäviä teok- sia, mutta joutuivat konserttielämässämme säveltäjän kuoleman jälkeen ja sodanjälkeisen modernis- min vuosina varjoon. Kun sinfonioita ei ole aikoinaan kustannettu eikä 6. sinfoniaa lukuun ottamatta koskaan painettu, kynnys teosten esille ottamiseen ja niihin tutustumiseen on ollut myöhemmin tar- peettoman korkea. -

Symphonic Poem Traumgesicht, Op. 70 by Erkki Melartin

Symphonic Poem Traumgesicht , Op. 70 by Erkki Melartin Principally, Erkki Melartin (1875–1937) thought of himself as a composer, although he also was a professional conductor, a professor of music theory and composition, and from 1911 on he also worked as the director of the Helsinki Conservatory – later the Sibelius Academy – for 25 years. In Melartin’s large oeuvre, e.g. his symphonies and the opera Aino were sig- nificant works when considering their artistic importance. However, they were left in obliv- ion after the composer’s death and during the post-war Modernism. Since Melartin’s large-scale works were left unpublished during the composer’s lifetime – apart from Symphony No. 6 –, there has been an unnecessarily high threshold for bringing up or getting acquainted with them. In order to promote their performing, and to help them become a living part of the music culture in Finland, the Erkki Melartin Society launched an editing and clean-copying project for Melartin’s symphonies in 2006. Besides the works of Jean Sibelius, the public of today should be given a possibility of hearing the more lyrical symphonic music of Melartin, which has been more influenced by the Finnish folk songs, the Finnish scenery, and the idyll of summer. Melartin saw himself mainly as a symphonic composer. Between 1903 and 1925, he com- posed six symphonies which mainly lean on Austro-German symphonic tradition. Back then, their premieres became substantial, patriotic events, and these works were per- formed also abroad, e.g. in Stockholm, Copenhagen, Riga, Moscow and Berlin. In addition to six symphonies, Melartin also composed three symphonic poems: Siikajoki (Op. -

Vignal Sibelius-And-Mahler.Pdf

Sibelius and Mahler Marc Vignal (tr. from French Ilkka Oramo) We know that Jean Sibelius (1865–1957) and Gustav Mahler (1860–1911) met only once: in 1907 in Helsinki, where Mahler conducted Kajanus’s orchestra on Friday November 1 in a concert with works by Beethoven and Wagner, his favorite composers. In his book on Sibelius, published almost thirty years later (1935), Karl Ekman Jr (1895–1961) conveys a conversation between the two composers reproduced innumerable times since then, putting into Sibelius’s mouth words, the authenticity of which is far from guaranteed: “Mahler and I spent much time in each other’s company. Mahler’s grave heart-trouble forced him to lead an ascetic life and he was not fond of dinners and banquets. Contact was established between us in some walks, during which we discussed all the great questions of music thoroughly. When our conversation touched the essence of symphony, I said that I admired its severity and style and the profound logic that created an inner connection between all the motifs. This was the experience I had come to in composing. Mahler’s opinion was just the reverse. ‘Nein, die Symphonie muss sein wie die Welt, Sie muss alles umfassen.’ [‘No, symphony must be like the world. It must embrace everything.’] Personally, Mahler was very modest. [...] A very interesting person. I respected him as a personality, his ethically exalted qualities as a man and an artist, in spite of his ideas on art being different than mine. I did not wish him to think that I had only looked him up in order to get him interested in my compositions.