Vignal Sibelius-And-Mahler.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9 September 2021

9 September 2021 12:01 AM Uuno Klami (1900-1961) Serenades joyeuses Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Jussi Jalas (conductor) FIYLE 12:07 AM Johann Gottlieb Graun (c.1702-1771) Sinfonia in B flat major, GraunWV A:XII:27 Kore Orchestra, Andrea Buccarella (harpsichord) PLPR 12:17 AM Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Violin Sonata in G minor Janine Jansen (violin), David Kuijken (piano) GBBBC 12:31 AM Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) Slavonic March in B flat minor 'March Slave' BBC Philharmonic, Rumon Gamba (conductor) GBBBC 12:41 AM Maria Antonia Walpurgis (1724-1780) Sinfonia from "Talestri, Regina delle Amazzoni" - Dramma per musica Batzdorfer Hofkapelle, Tobias Schade (director) DEWDR 12:48 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Sonata for piano (K.281) in B flat major Ingo Dannhorn (piano) AUABC 01:00 AM Luigi Boccherini (1743-1805) Quintet for guitar and strings in D major, G448 Zagreb Guitar Quartet, Varazdin Chamber Orchestra HRHRT 01:19 AM Carl Nielsen (1865-1931) Symphony No.3 (Op.27) "Sinfonia espansiva" Janne Berglund (soprano), Johannes Weisse (baritone), Stavanger Symphony Orchestra, Niklas Willen (conductor) NONRK 02:01 AM Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Estampes, L.100 Kira Frolu (piano) ROROR 02:14 AM Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) Etude in C minor Op.10'12 'Revolutionary' Kira Frolu (piano) ROROR 02:17 AM Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) Etude in E major, Op.10'3 Kira Frolu (piano) ROROR 02:20 AM Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) Etude in C minor Op.25'12 Kira Frolu (piano) ROROR 02:23 AM Constantin Silvestri (1913-1969) Chants nostalgiques, -

Tempus Magazine February 12, 2021

RE:VIEW RE:VIEW ITALIAN STYLE STEPS THE SUMMER OF MUSIC BEGINS WITH THE RETURN OF THE BBC PROMS ONTO THE PODIUM Plus + • Earl Spencer dives into English history • HOFA Gallery celebrates the mothers of mankind • Start your engines for Salon Privé • Save the Date: your luxury events calendar PROUD TO BE THE OFFICIAL TOAST OF FORMULA 1® #FERRARITRENTOF1 DRINK RESPONSIBLY The F1 logo, FORMULA 1, F1, GRAND PRIX and related marks are trademarks of Formula One Licensing BV, a Formula 1 company. All rights reserved. 90 91 MUSIC | BBC PROMS Summer of sound PARALLEL UNIVERSES Composer Britta Byström presents a world premiere inspired by the notion of a ‘hierarchical multiverse’ The world’s biggest classical festival returns to and violinist Jennifer Pike takes on Sibelius’ Violin Concerto in D minor, op.47. the Royal Albert Hall for six weeks of music 10 August STRAVINSKY FROM MEMORY The Aurora Orchestra returns to the Proms to mark the 50th anniversary of Igor Stravinsky’s death with a rendition of his Firebird Suite, performed entirely from memory. 11 August ABEL SELAOCOE: AFRICA MEETS EUROPE South African cellist Abel Selaocoe redefines his instrument in this blend of traditional styles with improv, singing and body percussion. A delight of boundary-crossing fusion. 15 August THE BBC SINGERS & SHIVA FESHAREKI Experimental composer and turntable artist Feshareki joins conductor Sofi Jeannin and the BBC Singers for a choral playlist that brings the Renaissance to the present day. 19 August his year, the Royal Albert Hall marks it was an opportunity to build a repertoire of its 150th anniversary, and what better rare and under-performed works, as well as T way to celebrate than by welcoming introducing new composers. -

Correspondences – Jean Sibelius in a Forest of Image and Myth // Anna-Maria Von Bonsdorff --- FNG Research Issue No

Issue No. 6/20161/2017 CorrespondencesNordic Art History in – the Making: Carl Gustaf JeanEstlander Sibelius and in Tidskrift a Forest för of Bildande Image and Konst Myth och Konstindustri 1875–1876 Anna-Maria von Bonsdorff SusannaPhD, Chief Pettersson Curator, //Finnish PhD, NationalDirector, Gallery,Ateneum Ateneum Art Museum, Art Museum Finnish National Gallery First published in RenjaHanna-Leena Suominen-Kokkonen Paloposki (ed.), (ed.), Sibelius The Challenges and the World of Biographical of Art. Ateneum ResearchPublications in ArtVol. History 70. Helsinki: Today Finnish. Taidehistoriallisia National Gallery tutkimuksia / Ateneum (Studies Art inMuseum, Art History) 2014, 46. Helsinki:81–127. Taidehistorian seura (The Society for Art History in Finland), 64–73, 2013 __________ … “så länge vi på vår sida göra allt hvad i vår magt står – den mår vara hur ringa Thankssom to his helst friends – för in att the skapa arts the ett idea konstorgan, of a young värdigt Jean Sibeliusvårt lands who och was vår the tids composer- fordringar. genius Stockholmof his age developed i December rapidly. 1874. Redaktionen”The figure that. (‘… was as createdlong as wewas do emphatically everything we anguished, can reflective– however and profound. little that On maythe beother – to hand,create pictures an art bodyof Sibelius that is showworth us the a fashionable, claims of our 1 recklesscountries and modern and ofinternational our time. From bohemian, the Editorial whose staff, personality Stockholm, inspired December artists to1874.’) create cartoons and caricatures. Among his many portraitists were the young Akseli Gallen-Kallela1 and the more experienced Albert Edelfelt. They tended to emphasise Sibelius’s high forehead, assertiveThese words hair were and addressedpiercing eyes, to the as readersif calling of attention the first issue to ofhow the this brand charismatic new art journal person created compositionsTidskrift för bildande in his headkonst andoch thenkonstindustri wrote them (Journal down, of Finein their Arts entirety, and Arts andas the Crafts) score. -

Sibelius Society

UNITED KINGDOM SIBELIUS SOCIETY www.sibeliussociety.info NEWSLETTER No. 84 ISSN 1-473-4206 United Kingdom Sibelius Society Newsletter - Issue 84 (January 2019) - CONTENTS - Page 1. Editorial ........................................................................................... 4 2. An Honour for our President by S H P Steadman ..................... 5 3. The Music of What isby Angela Burton ...................................... 7 4. The Seventh Symphonyby Edward Clark ................................... 11 5. Two forthcoming Society concerts by Edward Clark ............... 12 6. Delights and Revelations from Maestro Records by Edward Clark ............................................................................ 13 7. Music You Might Like by Simon Coombs .................................... 20 8. Desert Island Sibelius by Peter Frankland .................................. 25 9. Eugene Ormandy by David Lowe ................................................. 34 10. The Third Symphony and an enduring friendship by Edward Clark ............................................................................. 38 11. Interesting Sibelians on Record by Edward Clark ...................... 42 12. Concert Reviews ............................................................................. 47 13. The Power and the Gloryby Edward Clark ................................ 47 14. A debut Concert by Edward Clark ............................................... 51 15. Music from WW1 by Edward Clark ............................................ 53 16. A -

Ilmari Krohn and the Early French Contacts of Finnish Musicology: Mobility, Networking and Interaction1 Helena Tyrväinen

Ilmari Krohn and the Early French Contacts of Finnish Musicology: Mobility, Networking and Interaction1 Helena Tyrväinen Abstract Conceived in memory of the late Professor of Musicology of the Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre Urve Lippus (1950–2015) and to honour her contribution to music history research, the article analyses transcultural relations and the role of cultural capitals in the discipline during its early phase in the uni- versity context. The focus is on the early French contacts of the founder of institutional Finnish musicology, the Uni- versity of Helsinki Professor Ilmari Krohn (1867–1960) and his pupils. The analysis of Krohn’s mobility, networking and interaction is based on his correspondence and documentation concerning his early congress journeys to London (1891) and to Paris (1900). Two French correspondents stand out in this early phase of his career as a musicologist: Julien Tiersot in the area of comparative research on traditional music, and Georges Houdard in the field of Gregorian chant and neume notation. By World War I Krohn was quite well-read in French-language musicology. Paris served him also as a base for international networking more generally. Accomplished musicians, Krohn and his musicology students Armas Launis, Leevi Madetoja and Toivo Haapanen even had an artistic bond with French repertoires. My results contradict the claim that early Finnish musicology was exclusively the domain of German influences. In an article dedicated to the memory of Urve Lip- Academy of Music and Theatre, Urve considered pus, who was for many years Professor of Musicol- that a knowledge of the music history of Finland, ogy and director of the discipline at the Estonian as well as of the origins of music history writing Academy of Music and Theatre, it is appropriate in this neighbouring country, would be useful to to discuss international cooperation, mobility of Estonians. -

Jean Sibelius Zum 50. Todestag · Voces Intimae · Streichquartett D-Moll Op

JEAN SIBELIUS ZUM 50. TODEstAG · VOCES INTIMAE · STREICHQUARTEtt D-MOLL OP. 56 SKANDINAVISCHE SEHNSUCHT · 18. 22.09.2007 KULLERVO · FINLANDIA · SUITE FÜR ORCHEstER OP. 11 · ALLA MARCIA · SCHERZINO OP. 58 NR. 2 REVERIE OP. 58 NR. 1 · SINFONIE NR. 7 C-DUR OP. 105 · RAKASTAVA · ROMANZE A-DUR OP. 24 NR. 2 · KONZERT FÜR VIOLINE UND ORCHEstER D-MOLL OP. 47 · SO KLINGT NUR DORTMUND 2,50 E KONZERTHAUS DORTMUND · JEAN SIBELIUS ZUM 50. TODESTAG. SO KLINGT NUR DORTMUND. Abo: Jean Sibelius zum 50. Todestag – Festival-Pass I Wir bitten um Verständnis, dass Bild- und Tonaufnahmen während der Vorstellung nicht gestattet sind. GEFÖRDERT DURCH DIE FINNisCHE BOtsCHaft BERLIN 4 I 5 JEAN SIBELIUS ZUM 50. TODEstAG – META4 QUARTET D IENstAG, 18.09.2007 · 20.00 Dauer: ca. 1 Stunde 45 Minuten inklusive Pause Meta4 Quartet Antti Tikkanen Violine · Minna Pensola Violine Atte Kilpeläinen Viola · Tomas Djupsjöbacka Violoncello JEAN SibELIUS (1865 –1957) Fugue for Martin Wegelius JOUNI KaipaiNEN (1956 – ) Streichquartett Nr. 5 op. 70 Andante Sostenuto, semplice – Allegro con impeto e spiritoso Adagio misterioso sospirando – meno Adagio – Tempo primo -Pause- JEAN SibELIUS Streichquartett d-moll op. 56 »Voces Intimae« Andante. Allegro molto moderato Vivace Adagio di molto Allegro (ma pesante) Allegro Einführung mit Intendant Benedikt Stampa um 19.15 Uhr im Komponistenfoyer Gefördert durch Kunststiftung NRW 6I7 PROGRAMM JEAN SIBELIUS ZUM 50. TODEstAG – KLAVIERABEND ANttI SIIRALA · MIttWOCH, 19.09.2007 · 19.00 FRÉDÉRIC CHOpiN 24 Préludes op. 28 Prélude Nr. 1 C-Dur Dauer: ca. 2 Stunden inklusive Pause Prélude Nr. 2 a-moll Prélude Nr. 3 G-Dur Antti Siirala Klavier Prélude Nr. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 12, 1892-1893

FORD'S GRAND OPERA HOUSE, BALTIMORE. BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA. ARTHUR NIKISCH, Conductor. Twelfth Season, 1892-93. ONLY CONCERT IN BALTIMORE THIS SEASON, Monday Evening, October 31, 1892, At Eight o'clock. With Historical and Descriptive Notes by William F. Apthorp. PUBLISHED BY C A. ELLIS, MANAGER. The Mason &. Hamlin Piano has been exhibited in three Great World's Competitive Exhibitions, and has received the HIGHEST POSSIBLE AWARD at each one, as follows : AMSTERDAM, . 1888. NEW ORLEANS, . 1888. JAMAICA, . ... 1891. Because of an improved method of construction, in- troduced in 1882 by this Company, the Mason Sc Hamlin PIANOFORTES Are more durable and stand in tune longer than any others manufactured. CAREFUL INSPECTION RESPECTFULLY INVITED. BOSTON. NEW YORK. CHICAGO. Local Representatives, OTTO SUTRO & CO., - BALTIMORE (2) Boston Fords _ i 4i// Grand Opera Symphony f| House. \Jl Of Ifc/O Li CjL Season of 1892-93. Mr. ARTHUR NIKISCH, Conductor. Monday Evening, October 31, At Eight. PROGRAMME. " Karl Goldmark ------ Overture, " Sakuntala " K. M. von Weber - Aria from " Oberon," " Ocean, thou mighty monster y Richard Wagner - Vorspiel and "Liebestod" (Prelude and " Love-death') y " from " Tristan und Isolde Franz Liszt - - - - Song with Orchestra, "Loreley" Ludwig van Beethoven - - Symphony in C minor, No. 5, Op. 67 Allegro con brio (C minor), - 2-4. Andante con moto (A-flat major), - - 3-8. | Scherzo, Allegro (C minor), - 3-4. i Trio (C major), - 3-4. Finale, Allegro (C major), - 4-4. Soloist, Miss EMMA JUCH, (3) : SHORE LINE BOSTON TA NEW YORK NEW YORK TO1 \J BOSTON Trains leave either city, week-days, except as noted DAY EXPRESS at 10.00 A.M. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

2005 Summer Bridge

he Sibelius Academy, located in Helsinki, Finland, was founded in T1882. The Academy is named for the internationally renowned and loved Finnish composer Jean Sibelius. As a state music academy, the Sibelius Academy enjoys university status and is an integral part of the system of higher education in Finland. It is the only university of music in Finland, and the largest in Scandinavia. World-class student musicians from the prestigious music academy are invited annually by Finlandia University to present a series of outstanding public performances. This year, three consecutive evening concerts will be presented at the historic Calumet Theatre; an additional festival concert will be presented at the Holy Cross Lutheran Church in Wheaton, IL. summer 2005 This year’s award-winning performers are solo pianist Marko Mustonen, piano-cello duo Anna Kuvaja and Alexander Gebert, and chamber music quartet Soli Amici (Annu Salminen, Performance Dates horn; Paula Kitinoja, oboe; Timo Jäntti, Calumet Theatre Holy Cross Lutheran Church bassoon; and Kaisa Koivula, clarinet; with piano Calumet, MI Wheaton, IL accompanist Jussi Rinta). on August 3 rd, 4 th, and 5 th on August 1st SEVENTH ANNUAL SIBELIUS ACADEMY MUSIC FESTIVAL TICKET ORDER FORM Name: ________________________________________________ CALUMET THEATRE 340 Sixth Stree t • P.O. Box 167 • Calumet, MI 49913 Address: ________________________________________________ Box Office: (906) 337-2610 • Fax: (906) 337-4073 Address: ________________________ Phone: ________________ E-mail: [email protected] http://www.calu mettheatre.com CALUMET THEATRE ONLY Date Artist Tickets Price Qty Best Available Seat On Total Aug. 3, 2005: Soli Amici: chamber music quartet Adult $15 ______ K Main Floor K Balcony $ ______ Jussi Rintä, piano (accompaniment) Student/Senior $10 ______ K Main Floor K Balcony $ ______ Aug. -

Zur Reger-Rezeption Des Wiener Vereins Für Musikalische Privataufführungen

3 „in ausgezeichneten, gewissenhaften Vorbereitungen, mit vielen Proben“ Zur Reger-Rezeption des Wiener Vereins für musikalische Privataufführungen Mit Max Regers frühem Tod hatte der unermüdlichste Propagator seines Werks im Mai 1916 die Bühne verlassen. Sein Andenken in einer sich rasant verändernden Welt versuchte seine Witwe in den Sommern 1917, 1918 und 1920 abgehaltenen Reger-Festen in Jena zu wahren, während die schon im Juni 1916 gegründete Max- Reger-Gesellschaft (MRG) zwar Reger-Feste als Kern ihrer Aufgaben ansah, we- gen der schwierigen politischen und fnanziellen Lage aber nicht vor April 1922 ihr erstes Fest in Breslau veranstalten konnte. Eine kontinuierliche Auseinandersetzung zwischen diesen zwar hochkarätigen, jedoch nur sporadischen Initiativen bot Arnold Schönbergs Wiener „Verein für mu- sikalische Privataufführungen“, dessen Musiker, anders als die der Reger-Feste, in keinem persönlichen Verhältnis zum Komponisten gestanden hatten. Mit seinen idealistischen Zielen konnte der Verein zwar nur drei Jahre überleben, war aber in der kurzen Zeit seines Wirkens vom ersten Konzert am 29. Dezember 1918 bis zum letzten am 5. Dezember 1921 beeindruckend aktiv: In der ersten Saison veranstal- tete er 26, in der zweiten 35, in der dritten sogar 41 Konzerte, während die vorzeitig beendete vierte Saison nur noch elf Konzerte bringen konnte. Berücksichtigt wur- den laut Vereinsprospekt Werke aller Stilrichtungen unter dem obersten Kriterium einer eigenen Physiognomie ihres Schöpfers. Pädagogisches Ziel war es, das Pu- blikum auf -

Download Program Notes

Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 43 Jean Sibelius hanks to benefactions arranged by Axel four tone poems based on characters from TCarpelan, a Finnish man-about-the-arts Dante’s Divine Comedy . But once Sibelius re - and the eventual dedicatee of this work, Jean turned to Finland that June, he began to rec - Sibelius and his family were able to undertake ognize that what was forming out of his a trip to Italy from February to April 1901. So sketches was instead a full-fledged sym - it was that much of the Second Symphony phony — one that would end up exhibiting was sketched in the Italian cities of Florence an extraordinary degree of unity among its and, especially, Rapallo, where Sibelius sections. With his goal now clarified, Sibelius rented a composing studio apart from the worked assiduously through the summer and home in which his family was lodging. fall and reached a provisional completion of Aspects of the piece had already begun to his symphony in November 1901. Then he form in his mind almost two years earlier, al - had second thoughts, revised the piece pro - though at that point Sibelius seems to have foundly, and definitively concluded the Sec - assumed that his sketches would end up in ond Symphony in January 1902. various separate compositions rather than in The work’s premiere, two months later, a single unified symphony. Even in Rapallo marked a signal success, as did three sold-out he was focused on writing a tone poem. He performances during the ensuing week. The reported that on February 11, 1901, he enter - conductor Robert Kajanus, who would be - tained a fantasy that the villa in which his come a distinguished interpreter of Sibelius’s studio was located was the fanciful palace of works, was in attendance, and he insisted Don Juan and that he himself was the that the Helsinki audiences had understood amorous, amoral protagonist of that legend. -

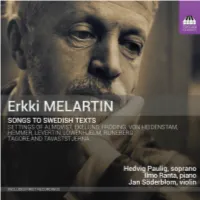

TOCC0416DIGIBKLT.Pdf

ERKKI MELARTIN Songs to Swedish Texts Four Runeberg Settings 1 Mellan friska blomster (‘Among budding fowers’), Op. 172, No. 2 (1931?) 0:48 2 Flickans klagan (‘The Girl's Lament’), Op. 14, No. 1 (1901)* 2:16 3 Törnet (‘The Thornèd Rose’), Op. 170, No. 3 (1931) 1:36 Hedvig Paulig, soprano 4 Stum kärlek (‘Silent Love’), Op. 116, No. 5 (1919) 2:21 Ilmo Ranta, piano Jan Söderblom, violin 10 – 13 , 22 Five Hemmer Settings 5 Mitt hjärta behöver… (‘My heart requires…’), Op. 116, No. 6 (1919) 2:30 6 Under häggarna (‘Under the Bird-Cherry Trees’), Op. 86, No. 3 (1914) 1:44 7 Bön om ro (‘Prayer for Rest’), Op. 122, No. 6 (1924) 2:03 8 Elegie (‘Elegy‘), Op. 96, No. 1 (1916) 2:56 9 Akvarell (‘Watercolour‘), Op. 96, No. 2 (1916) 1:56 Tagoresånger (‘Tagore Songs’), Op. 105 11:54 10 No. 1 Skyar (‘Clouds’) (1914) 3:20 11 No. 2 Sagan om vårt hjärta (‘The Tale of our Heart’) (1918) 2:24 12 No. 3 Smärtan (‘The Pain’) (1918)** 2:53 13 No. 4 Allvarsdagen (‘On the Last Day’) (1914) 3:17 Other Swedish Settings 14 Skåda, skåda hur det våras (‘See, see how the spring appears’), Op. 117, No. 2 (Löwenhjelm; 1921)* 1:57 15 I skäraste morgongryning (‘As aurora broke’), Op. 21, No. 2 (Tavaststjerna; 1896) 3:20 16 Marias vaggsång (‘Mary’s Lullaby’), Op. 3, No. 1 (Levertin; 1897)*** 3:24 17 Maria, Guds moder (‘Mary, Mother of God’), Op. 151, No. 2 (R. Ekelund; 1928) 3:13 18 Stjärnor (‘Stars’), Op.