The EU, Resilience and the MENA Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Top Current Affairs of the Week (7 July – 13 July 2019)

www.gradeup.co Top Current Affairs of the week (7 July – 13 July 2019) 1. Brazil wins the Copa America 2019 Title • Brazil defeated Peru 3-1 to win its first Copa America title since 2007. • Jesus scored the decisive goal after a penalty from Peru captain Paolo Guerrero cancelled out Everton’s opener for hosts Brazil at Rio de Janeiro’s Maracana stadium. • A last-minute penalty from substitute Richarlison sealed a win for Brazil which handed the South American giantstheir ninth Copa triumph and first since 2007. • Argentina took third place by beating Chile 2–1 in the third-place match. • Brazil's veteran right-back Dani Alves was player of the tournament. Related Information: • The 2019 Copa América (46th edition) was the international men's association football championship organized by South America's football ruling body CONMEBOL. • It was held in Brazil (between 14 June to 7 July 2019) at 6 venues across the country. 2. Vinesh Phoga & Divya Kakran wins the Gold medal at Grand Prix of Spain • India’s wrestler Vinesh Phogat (in 53 Kg category) and Divya Kakran (in 68 kg category) have won Gold Medal at the Grand Prix of Spain. • Vinesh comfortably beat Peru's Justina Benites and Russia's Nina Minkenova before getting the better of Dutch rival Jessica Blaszka in the final. • Among others, World Championship bronze medallist Pooja Dhanda (57kg), Seema (50kg), Manju Kumari (59kg) and Kiran (76kg) won silver medal. • India finished second with 130 points in team championship behind Russia (165- points) 3. Hima Das clinches gold in Kutno Athletics Meet in Poland • Indian sprinter Hima Das (19-years) won her second international gold in women's 200m with a top finish at the Kutno Athletics Meet in Poland. -

Ranking 2019 Po Zaliczeniu 182 Dyscyplin

RANKING 2019 PO ZALICZENIU 182 DYSCYPLIN OCENA PKT. ZŁ. SR. BR. SPORTS BEST 1. Rosja 384.5 2370 350 317 336 111 33 2. USA 372.5 2094 327 252 282 107 22 3. Niemcy 284.5 1573 227 208 251 105 17 4. Francja 274.5 1486 216 192 238 99 15 5. Włochy 228.0 1204 158 189 194 96 10 6. Wielka Brytania / Anglia 185.5 915 117 130 187 81 5 7. Chiny 177.5 1109 184 122 129 60 6 8. Japonia 168.5 918 135 135 108 69 8 9. Polska 150.5 800 103 126 136 76 6 10. Hiszpania 146.5 663 84 109 109 75 6 11. Australia 144.5 719 108 98 91 63 3 12. Holandia 138.5 664 100 84 96 57 4 13. Czechy 129.5 727 101 114 95 64 3 14. Szwecja 123.5 576 79 87 86 73 3 15. Ukraina 108.0 577 78 82 101 52 1 16. Kanada 108.0 462 57 68 98 67 2 17. Norwegia 98.5 556 88 66 72 42 5 18. Szwajcaria 98.0 481 66 64 89 59 3 19. Brazylia 95.5 413 56 63 64 56 3 20. Węgry 89.0 440 70 54 52 50 3 21. Korea Płd. 80.0 411 61 53 61 38 3 22. Austria 78.5 393 47 61 83 52 2 23. Finlandia 61.0 247 30 41 51 53 3 24. Nowa Zelandia 60.0 261 39 35 35 34 3 25. Słowenia 54.0 278 43 38 30 29 1 26. -

Sportonsocial 2018 1 INTRODUCTION

#SportOnSocial 2018 1 INTRODUCTION 2 RANKINGS TABLE 3 HEADLINES 4 CHANNEL SUMMARIES A) FACEBOOK CONTENTS B) INSTAGRAM C) TWITTER D) YOUTUBE 5 METHODOLOGY 6 ABOUT REDTORCH INTRODUCTION #SportOnSocial INTRODUCTION Welcome to the second edition of #SportOnSocial. This annual report by REDTORCH analyses the presence and performance of 35 IOC- recognised International Sport Federations (IFs) on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and YouTube. The report includes links to examples of high-performing content that can be viewed by clicking on words in red. Which sports were the highest climbers in our Rankings Table? How did IFs perform at INTRODUCTION PyeongChang 2018? What was the impact of their own World Championships? Who was crowned this year’s best on social? We hope you find the report interesting and informative! The REDTORCH team. 4 RANKINGS TABLE SOCIAL MEDIA RANKINGS TABLE #SportOnSocial Overall International Channel Rank Overall International Channel Rank Rank* Federation Rank* Federation 1 +1 WR: World Rugby 1 5 7 1 19 +1 IWF: International Weightlifting Federation 13 24 27 13 2 +8 ITTF: International Table Tennis Federation 2 4 10 2 20 -1 FIE: International Fencing Federation 22 14 22 22 3 – 0 FIBA: International Basketball Federation 5 1 2 18 21 -6 IBU: International Biathlon Union 23 11 33 17 4 +7 UWW: United World Wrestling 3 2 11 9 22 +10 WCF: World Curling Federation 16 25 12 25 5 +3 FIVB: International Volleyball Federation 7 8 6 10 23 – 0 IBSF: International Bobsleigh and Skeleton Federation 17 15 19 30 6 +3 IAAF: International -

Middle-Easterners and North Africans in America Power of the Purse: Middle-Easterners and North Africans in America

JANUARY 2019 POWER OF THE PURSE: Middle-Easterners and North Africans in America Power of the Purse: Middle-Easterners and North Africans in America Paid for by the Partnership for a New American Economy Research Fund CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Introduction 4 Income and Tax Contributions 6 Spending Power 9 Entrepreneurship 11 Filling Gaps in the Labor Force 13 Communities Benefitting from MENA Immigrants 17 MENA Immigrants in Detroit 21 Conclusion 23 Methodology Appendix 24 Endnotes 26 © Partnership for a New American Economy Research Fund. Power of the Purse: Middle-Easterners and North Africans in America | Executive Summary Executive Summary ver the last few decades, immigrants from the born residents from the Middle East and North Africa Middle East and North Africa (MENA) have make critically important contributions to our country O gone from a small minority of the immigrants through their work as everything from physicians to in America to a growing and highly productive segment technology workers to entrepreneurs. The contributions of the U.S. economy. Yet very little attention has been they make as taxpayers support the growth of many paid to the economic contributions of MENA immigrants. key cities, including several in the Midwest. And their This occurs for a variety of reasons. First, despite their expenditures as consumers support countless growing numbers they still represent one of the smallest U.S. businesses. groups of American newcomers, numbering fewer than 1.5 million people—or less than 0.5 percent of the U.S. The contributions Middle Eastern population overall. Second, the U.S. Census has a short and North African immigrants history of tracking socioeconomic data on immigrants from the Middle East.1 make as taxpayers support the growth of many key cities, Foreign-born residents including several in the Midwest. -

Lebanon: Background and US Policy

Lebanon: Background and U.S. Policy name redacted Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs April 4, 2014 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R42816 Lebanon: Background and U.S. Policy Summary Lebanon’s small geographic size and population belie the important role it has long played in the security, stability, and economy of the Levant and the broader Middle East. Congress and the executive branch have recognized Lebanon’s status as a venue for regional strategic competition and have engaged diplomatically, financially, and at times, militarily to influence events there. For most of its independent existence, Lebanon has been torn by periodic civil conflict and political battles between rival religious sects and ideological groups. External military intervention, occupation, and interference have exacerbated Lebanon’s political struggles in recent decades. Lebanon is an important factor in U.S. calculations regarding regional security, particularly regarding Israel and Iran. Congressional concerns have focused on the prominent role that Hezbollah, an Iran-backed Shia Muslim militia, political party, and U.S.-designated terrorist organization, continues to play in Lebanon and beyond, including its recent armed intervention in Syria. Congress has appropriated more than $1 billion since the end of the brief Israel-Hezbollah war of 2006 to support U.S. policies designed to extend Lebanese security forces’ control over the country and promote economic growth. The civil war in neighboring Syria is progressively destabilizing Lebanon. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, more than 1 million predominantly Sunni Syrian refugees have fled to Lebanon, equivalent to close to one-quarter of Lebanon’s population. -

The-Recitals-May-2019.Pdf

INDEX Message From The Desk Of Director 1 1. Feature Article 2-12 a. Universal Basic Income b. India In Indo-Pacific Region c. UNSC: Evaluation And Reforms 2. Mains Q&A 13-42 3. Prelims Q&A 43-73 4. Bridging Gaps 74-100 VAJIRAM AND RAVI The Recitals (May 2019) Dear Students The preparation of current affairs magazine is an evolutionary process as its nature and content keeps changing according to the demands of Civil Service Exam. As you are aware about the importance of current affairs for the prelims as well as mains exam, our aim is to follow an integrated approach covering all stages of examination from prelims to interview. Keeping these things in mind, we, at Vajiram and Ravi Institute, are always in the process of evolving our self so as to help aspirants counter the challenges put forward by UPSC. In fulfillment of our objective and commitment towards the students, we have introduced some changes in our current affairs magazine. The CA Magazines, now with the name of “The Recitals”, will have four sections. These are: 1. Feature Article: As you are aware of the fact that civil service mains exam has become quite exhaustive and analytical, especially since 2013 after the change in syllabus, we have decided to focus on 2-3 topics every month that will provide an insight into the issue so as to help students understand the core of the issue. This will help in Essay writing as well as Mains Exam. 2. Mains Q&A: New students quite often struggle to find out that in what way the given topic is useful for them and in what form questions can be framed from the article. -

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA)

Regional strategy for development cooperation with The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) 2006 – 2008 The Swedish Government resolved on 27 April 2006 that Swedish support for regional development cooperation in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA region) during the period 2006-2008 should be conducted in accordance with the enclosed regional strategy. The Government authorized the Swedish International Development Coope- ration Agency (Sida) to implement in accordance with the strategy and decided that the financial framework for the development cooperation programme should be SEK 400–500 million. Regional strategy for development cooperation with the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) 2006 – 2008 Contents 1. Summary ........................................................................................ 2 2. Conclusions of the regional assessment ........................................... 3 3. Assessment of observations: Conclusions ......................................... 6 4. Other policy areas .......................................................................... 8 5. Cooperation with other donors ........................................................ 10 6. The aims and focus of Swedish development cooperation ................ 11 7. Areas of cooperation with the MENA region ..................................... 12 7.1 Strategic considerations ............................................................. 12 7.2 Cooperation with the Swedish Institute in Alexandria and ............... 14 where relevant with the Section for -

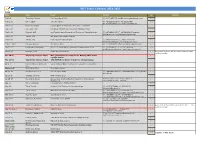

WTF Event Calendar 2014-2015 2014 Date Place Event Contact G Remark

WTF Event Calendar 2014-2015 2014 Date Place Event Contact G Remark Feb 8-9 Trelleborg, Sweden Trelleborg Open 2014 (T) +46709922594 [email protected] G-1 Feb 11-16 Luxor, Egypt 1st Luxor Open (T) +20222631737 (F) +20222617576 G-2 [email protected] / www.egypt-tkd.org Feb 13-16 Montreal, Canada Canada Open International Taekwondo Tournament G-1 Feb 18-24 Las Vegas, USA U.S Open International Taekwondo Championships G-2 Feb 20-22 Fujairah, UAE 2nd Fujairah Open International Taekwondo Championships (T) +97192234447 (F) +97192234474 fujairah- G-1 [email protected] / [email protected] Feb 21-23 Tehran, Iran 4th Asian Clubs Championships N/A Feb 24-26 Tehran, Iran 25th Fajr International Open (T) +982122242441 (F) +982122242444 G-1 [email protected] / www.fajr.iritf.org.ir Feb 27 - Mar 1 Manama, Bahrain 6th Bahrain Open (T) +73938888350 / [email protected] G-1 Mar 15-16 Eindhoven, Netherlands 41st Lotto Dutch Open Taekwondo Championships 2014 (T) +31235428867 (F) +31235428869 G-2 [email protected] / www.taekwondobond.nl Mar 15-17 Santiago, Chile South American Games G-1 Last event in March will be counted into the April ranking for GP1. Mar 20-21 Taipei City, Chinese Taipei WTF Qualification Tournament for Nanjing 2014 Youth N/A Olympic Games Mar 23-26 Taipei City, Chinese Taipei 10th WTF World Junior Taekwondo Championships N/A Apr 4-6 Santo Domingo, Dominican Santo Domingo Open International Taekwondo Tournament G-1 Rep. [Canceled] Kish Island, Iran West Asian Games G-1 Apr 11-13 Hamburg. Germany German Open -

Explaining the MENA Paradox: Rising Educational Attainment, Yet Stagnant Female Labor Force Participation

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11385 Explaining the MENA Paradox: Rising Educational Attainment, Yet Stagnant Female Labor Force Participation Ragui Assaad Rana Hendy Moundir Lassassi Shaimaa Yassin MARCH 2018 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 11385 Explaining the MENA Paradox: Rising Educational Attainment, Yet Stagnant Female Labor Force Participation Ragui Assaad Moundir Lassassi University of Minnesota, ERF and IZA Center for Research in Applied Economics for Development Rana Hendy Doha Institute for Graduate Studies Shaimaa Yassin and ERF University of Lausanne (DEEP) and University of Le Mans (GAINS-TEPP) MARCH 2018 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. -

Vol.11 No 16 August 30, 2019.Pmd

1 Nuclear, MissileNuclear, Missile & Space Digest & Space Digest Volume 11, Number 16 A Fortnightly Newsletter from the Indian Pugwash Society August 31, 2019 Convenor A. India Cabinet approves MoU between India and Tunisia on Cooperation in the Amb. Sujan R. Chinoy Exploration and Use of Outer Space for Peaceful Purposes ISRO announces Vikram Sarabhai Journalism Award in Space Science, Technology and Research 2-day exhibition on DAE Technologies: Empowering India through Technology, inaugurated in New Delhi Vikram lander will land on Moon as a tribute to Vikram Sarabhai from crores of Indians: PM Shri Narendra Modi Arms tangle Nuke plants' rescue jolts conservatives, environmentalist Earth as viewed by Chandrayaan-2: Isro shares 1st pictures Indian science has landmark moment at ITER, a global effort to create first- Executive Council ever nuclear fusion device Cdr. (Dr.) Probal K. Ghosh Chandrayaan 2: When will Lunar spacecraft reach Moon's orbit? ISRO reveals date Air Marshal S. G. Inamdar ISRO's new commercial arm gets first booking for launch (Retd.) ISRO's success is Vikram Sarabhai's lasting legacy Dr. Roshan Khanijo B. China Amb. R. Rajagopalan New port will host sea-based space launches Dr. Rajesh Rajagopalan Shanghai kicks off military recruitment, targeting college graduates Shri Dinesh Kumar China builds more powerful 'eyes' to observe the sun Yadvendra Commander of PLA Garrison in HK says violence 'totally intolerant' 7th Military World Games torch relay starts from Nanchang China's micro lunar orbiter crashes into Moon under control Russian deputy defense minister: China-Russian relations help safeguard international stability China opposes U.S. -

2018 Near East and North Africa Regional Overview of Food Security

2 018 Near East and North Africa REGIONAL OVERVIEW OF FOOD SECURITY AND NUTRITION RURAL TRANSFORMATION-KEY FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT IN THE NEAR EAST AND NORTH AFRICA COVER PHOTOGRAPH A Farmer cultivating crops. ©FAO/Franco Mattioli 2 018 REGIONAL OVERVIEW OF FOOD SECURITY AND NUTRITION RURAL TRANSFORMATION-KEY FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT IN THE NEAR EAST AND NORTH AFRICA Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Cairo, 2019 RECOMMENDED CITATION: FAO. 2019. Rural transformation-key for sustainable development in the near east and North Africa. Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2018. Cairo. 80 pp. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. ISBN 978-92-5-131348-0 © FAO, 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial -Share Alike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/ 3.0/igo/legalcode/legalcode). Under the terms of this licence, this work may be copied, redistributed and adapted for non-commercial purposes, provided that the work is appropriately cited. -

MIDDLE EASTERN STUDIES Cilt Volume 6 • Sayı Number 2 • Ocak January 2015

Siyaset ve Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi Journal of Politics and International Relations RTADOĞU ETÜTLERİ MIDDLE EASTERN STUDIES Cilt Volume 6 • Sayı Number 2 • Ocak January 2015 • Syria’s Firestorm: Where from? Where to? William Harris • Hizballah’s Resilience During the Arab Uprisings Joseph Alagha Implications of the Arab Spring for Iran’s Policy towards the • Middle East Bayram Sinkaya Implications of the Arab Uprisings on the Islamist Movement: • Lessons from Ikhwan in Tunisia, Egypt and Jordan Nur Köprülü European Powers and the Naissance of Weak States in the • Arab Middle East After World War I 2 • Ocak Gudrun Harrer Unpredictable Power Broker: Russia’s Role in Iran’s Nuclear • Capability Development Muhammet Fatih Özkan & Gürol Baba • Israel and the Gas Resources of the Levant Basin A. Murat Ağdemir 6 • Sayı İranlı Kadınların Hatıratlarında İran-Irak Savaşı: Seyyide • Fiyatı: 12 TL Zehra Hoseyni’nin Da’sını Yorumlamak Metin Yüksel BOOK REVIEWS • The New Middle East: Protest and Revolution in the Arab World ORSAM Rümeysa Eldoğan ISSN: 1309-1557 ORSAM ORTADOĞU STRATEJİK ARAŞTIRMALAR MERKEZİ CENTER FOR MIDDLE EASTERN STRATEGIC STUDIES ORTADOĞU ETÜTLERİ MIDDLE EASTERN STUDIES Siyaset ve Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi Journal of Politics and International Relations Ocak 2015, Cilt 6, Sayı 2 / January 2015, Volume 6, No 2 www.orsam.org.tr Hakemli Dergi / Refereed Journal Yılda iki kez yayımlanır / Published biannualy Sahibi / Owner: Şaban KARDAŞ, TOPAZ A.Ş. adına / on behalf of TOPAZ A.Ş. Editör / Editor-in-Chief: Özlem TÜR Yardımcı Editör/ Associate Editor: Ali Balcı Kitap Eleştirisi Editörü/ Book Review Editor: Gülriz Şen Yönetici Editör / Managing Editör: Tamer KOPARAN Sorumlu Yazı İşleri Müdürü / Managing Coordinator: Habib HÜRMÜZLÜ YAYIN KURULU / EDITORIAL BOARD Meliha Altunışık Middle East Technical University İlker Aytürk Bilkent Universitesi Recep Boztemur Middle East Technical University Katerina Dalacoura London School of Economics F.