Backup of CIRCLES and SEEDS W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

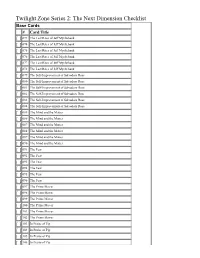

Twilight Zone Series 2: the Next Dimension Checklist

Twilight Zone Series 2: The Next Dimension Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 073 The Last Rites of Jeff Myrltebank [ ] 074 The Last Rites of Jeff Myrltebank [ ] 075 The Last Rites of Jeff Myrltebank [ ] 076 The Last Rites of Jeff Myrltebank [ ] 077 The Last Rites of Jeff Myrltebank [ ] 078 The Last Rites of Jeff Myrltebank [ ] 079 The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Rose [ ] 080 The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Rose [ ] 081 The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Rose [ ] 082 The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Rose [ ] 083 The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Rose [ ] 084 The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Rose [ ] 085 The Mind and the Matter [ ] 086 The Mind and the Matter [ ] 087 The Mind and the Matter [ ] 088 The Mind and the Matter [ ] 089 The Mind and the Matter [ ] 090 The Mind and the Matter [ ] 091 The Fear [ ] 092 The Fear [ ] 093 The Fear [ ] 094 The Fear [ ] 095 The Fear [ ] 096 The Fear [ ] 097 The Prime Mover [ ] 098 The Prime Mover [ ] 099 The Prime Mover [ ] 100 The Prime Mover [ ] 101 The Prime Mover [ ] 102 The Prime Mover [ ] 103 In Praise of Pip [ ] 104 In Praise of Pip [ ] 105 In Praise of Pip [ ] 106 In Praise of Pip [ ] 107 In Praise of Pip [ ] 108 In Praise of Pip [ ] 109 Nick of Time [ ] 110 Nick of Time [ ] 111 Nick of Time [ ] 112 Nick of Time [ ] 113 Nick of Time [ ] 114 Nick of Time [ ] 115 Shadow Play [ ] 116 Shadow Play [ ] 117 Shadow Play [ ] 118 Shadow Play [ ] 119 Shadow Play [ ] 120 Shadow Play [ ] 121 Four O'Clock [ ] 122 Four O'Clock [ ] 123 Four O'Clock [ ] 124 Four O'Clock [ ] 125 Four O'Clock [ ] 126 Four -

Collected Writings

THE DOCUMENTS O F TWENTIETH CENTURY ART General Editor, Jack Flam Founding Editor, Robert Motherwell Other titl es in the series available from University of California Press: Flight Out of Tillie: A Dada Diary by Hugo Ball John Elderfield Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt Barbara Rose Memo irs of a Dada Dnnnmer by Richard Huelsenbeck Hans J. Kl ein sc hmidt German Expressionism: Dowments jro111 the End of th e Wilhelmine Empire to th e Rise of National Socialis111 Rose-Carol Washton Long Matisse on Art, Revised Edition Jack Flam Pop Art: A Critical History Steven Henry Madoff Co llected Writings of Robert Mothen/le/1 Stephanie Terenzio Conversations with Cezanne Michael Doran ROBERT SMITHSON: THE COLLECTED WRITINGS EDITED BY JACK FLAM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Londo n University of Cali fornia Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1996 by the Estate of Robert Smithson Introduction © 1996 by Jack Flam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson, the collected writings I edited, with an Introduction by Jack Flam. p. em.- (The documents of twentieth century art) Originally published: The writings of Robert Smithson. New York: New York University Press, 1979. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-20385-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) r. Art. I. Title. II. Series. N7445.2.S62A3 5 1996 700-dc20 95-34773 C IP Printed in the United States of Am erica o8 07 o6 9 8 7 6 T he paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSII NISO Z39·48-1992 (R 1997) (Per111anmce of Paper) . -

The Machine Gun Hand: Robots, Performance, and American Ideology in the Twentieth Century

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2017 The aM chine Gun Hand: Robots, Performance, and American Ideology in the Twentieth Century Benjamin Michael Phelan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Phelan, Benjamin Michael, "The aM chine Gun Hand: Robots, Performance, and American Ideology in the Twentieth Century" (2017). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 4469. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/4469 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE MACHINE GUN HAND: ROBOTS, PERFORMANCE, AND AMERICAN IDEOLOGY IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Theatre by Benjamin Michael Phelan B.A., Brigham Young University, 2008 August 2017 Acknowledgments First, I must thank my major professor, friend, and advisor, Alan Sikes. Without his insightful comments throughout the years, this dissertation would have never gained much shape or inertia. I cannot thank him enough for his love and support and for the hours of meetings at Garden District Coffee or over the phone, helping me formulate my ideas into concrete chapters. This dissertation would not have been possible without the generous support of numerous faculty at Louisiana State University. -

Women and Arts : 75 Quotes

WOMEN AND ARTS : 75 QUOTES Compiled by Antoni Gelonch-Viladegut For the Gelonch Viladegut Collection website Paris, March 2011 1 SOMMARY A GLOBAL INTRODUCTION 3 A SHORT HISTORY OF WOMEN’S ARTISTS 5 1. The Ancient and Classic periods 5 2. The Medieval Era 6 3. The Renaissance era 7 4. The Baroque era 9 5. The 18th Century 10 6. The 19th Century 12 7. The 20th Century 14 8. Contemporary artists 17 A GENERAL BIBLIOGRAPHY 19 75 QUOTES: WOMEN AND THE ART 21 ( chronological order) THE QUOTES ORDERED BY TOPICS 30 Art’s Definition 31 The Artist and the artist’s work 34 The work of art and the creation process 35 Function and art’s understanding 37 Art and life 39 Adjectives’ art 41 2 A GLOBAL INTRODUCTION In the professional world we often speak about the "glass ceiling" to indicate a situation of not-representation or under-representation of women regarding the general standards presence in posts or roles of responsibility in the profession. This situation is even more marked in the world of the art generally and in the world of the artists in particular. In the art history women’s are not almost present and in the world of the art’s historians no more. With this panorama, the historian of the art Linda Nochlin, in 1971 published an article, in the magazine “Artnews”, releasing the question: "Why are not there great women artists?" Nochlin throws rejects first of all the presupposition of an absence or a quasi-absence of the women in the art history because of a defect of " artistic genius ", but is not either partisan of the feminist position of an invisibility of the women in the works of art history provoked by a sexist way of the discipline. -

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Hitmakers: The Teens Who Stole Pop Music. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Dionne Warwick: Don’t Make Me Over. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – Bobby Darin. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – [1] Leiber & Stoller; [2] Burt Bacharach. c2001. A & E Top 10. Show #109 – Fads, with commercial blacks. Broadcast 11/18/99. (Weller Grossman Productions) A & E, USA, Channel 13-Houston Segments. Sally Cruikshank cartoon, Jukeboxes, Popular Culture Collection – Jesse Jones Library Abbott & Costello In Hollywood. c1945. ABC News Nightline: John Lennon Murdered; Tuesday, December 9, 1980. (MPI Home Video) ABC News Nightline: Porn Rock; September 14, 1985. Interview with Frank Zappa and Donny Osmond. Abe Lincoln In Illinois. 1939. Raymond Massey, Gene Lockhart, Ruth Gordon. John Ford, director. (Nostalgia Merchant) The Abominable Dr. Phibes. 1971. Vincent Price, Joseph Cotton. Above The Rim. 1994. Duane Martin, Tupac Shakur, Leon. (New Line) Abraham Lincoln. 1930. Walter Huston, Una Merkel. D.W. Griffith, director. (KVC Entertaiment) Absolute Power. 1996. Clint Eastwood, Gene Hackman, Laura Linney. (Castle Rock Entertainment) The Abyss, Part 1 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss, Part 2 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: [1] documentary; [2] scripts. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: scripts; special materials. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – I. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – II. Academy Award Winners: Animated Short Films. -

Terra Nova, an Experiment in Creating Cult Televison for a Mass Audience

Syracuse University SURFACE S.I. Newhouse School of Public Media Studies - Theses Communications 8-2012 Terra Nova, An Experiment in Creating Cult Televison for a Mass Audience Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/ms_thesis Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Terra Nova, An Experiment in Creating Cult Televison for a Mass Audience" (2012). Media Studies - Theses. 5. https://surface.syr.edu/ms_thesis/5 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Media Studies - Theses by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When it aired in Fall 2011 on Fox, Terra Nova was an experiment in creating a cult television program that appealed to a mass audience. This thesis is a case study of that experiment. I conclude that the show failed because of its attempts to maintain the sophistication, complexity and innovative nature of the cult genre while simultaneously employing an overly simplistic narrative structure that resembles that of mass audience programming. Terra Nova was unique in its transmedia approach to marketing and storytelling, its advanced special effects, and its dystopian speculative fiction premise. Terra Nova’s narrative, on the other hand, presented a nostalgically simple moralistic landscape that upheld old-fashioned ideologies and felt oddly retro to the modern SF TV audience. Terra Nova’s failure suggests that a cult show made for this type of broad audience is impossible. -

PART II (A) Women Artists of the Renaissance in Italy

PART II (A) Women Artists of the Renaissance in Italy In the Italian Renaissance, among the women painters, there was no great female artist who was the equivalent of Raphael, Michelangelo, or Leonardo da Vinci. That is not to say that there were not some very good, even exceptional women artists from this period, and this in spite of social conditions that made it difficult for women to become artists at all. The Renaissance was an age of equality and intellectual advancement for mankind but this did not mean that women were seen to be on an equal footing with men. At the time of the Italian Renaissance, Athena, the goddess of wisdom, was revered and her image presented as that of a victorious woman soldier but real women were relatively invisible during this period, caught in the roles of wives and mothers and as yet uneducated. Some noblewomen continued to learn painting, drawing and embroidery in the convents but otherwise women did not have access to art training. This was the age of the individual artist or master, the artist as genius, and the status of both art and the artist was elevated in society. The important or "high" arts were now considered to be painting, which took the form of frescoes or panel painting, drawing, sculpture and architecture. It was impossible for women to become artists because of the master and apprentice system that existed in the art studios or bottegas. The master reigned supreme in his bottega and signed his name to all of the work that was produced there. -

A Grounded Theory Study of People Living with HIV/AIDS in the Thai

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Achieving Harmony of Mind A Grounded Theory Study of People Living with HIV/AIDS in the Thai Context A thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand Quantar Balthip 2010 Abstract The aims in this Straussian grounded theory inquiry were to gain better understanding of the meaning of spirituality and of the process of spiritual development in people living with HIV/AIDS in the Thai context. In Western contexts, spirituality has been described as the essence of human existence. However, in the Thai context, where Buddhist teachings underpin the understanding of life as body and mind, rather than as body, mind and spirit, the concept of spirituality is little understood by lay people. This gap in understanding called for an inductive approach to knowledge generation. HIV/AIDS is a life-altering and deeply stigmatized disease that results in significant distress and calls into question the meaning and purpose of life for many who are diagnosed with the disease. Nevertheless, some Thai people living with the disease successfully adjust their lives to their situation and are able to live with peace and harmony. These findings raise questions firstly as to the process by which those participants achieved peace and harmony despite the nature of the disease and the limited access to ARV drugs at the time of that study; and secondly as to whether or not the peace and harmony that they described could be linked to the Western concept of spirituality. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Owner\Desktop

The Twilight Zone Checklist SEASON ONE (1959-60) Episode Aired Stars U Where Is Everybody? 10/2/59 Earl Holliman, James Gregory One for the Angels 10/9/59 Ed Wynn, Murray Hamilton Mr. Denton on Doomsday 10/16/59 Dan Duryea, Martin Landau The 16-Millimeter Shrine 10/23/59 Ida Lupino, Martin Balsam Walking Distance 10/30/59 Gig Young, Frank Overton Escape Clause 11/06/59 David Wayne, Thomas Gomez The Lonely 11/13/59 Jack Warden, Jean Marsh Time Enough at Last 11/20/59 Burgess Meredith, Jacqueline DeWitt Perchance to Dream 11/27/59 Richard Conte, Suzanne Lloyd Judgment Night 12/04/59 Nehemiah Persoff, Ben Wright, Patrick Macnee And When The Sky Was Opened 12/11/59 Rod Taylor, Charles Aidman, Jim Hutton What You Need 12/25/59 Steve Cochran, Ernest Truex, Arlene Martel The Four of Us Are Dying 01/01/60 Harry Townes, Ross Martin Third from the Sun 01/08/60 Fritz Weaver, Joe Maross I Shot An Arrow Into the Air 01/16/60 Dewey Martin, Edward Binns The Hitch-Hiker 01/22/60 Inger Stevens, Leonard Strong The Fever 01/29/60 Everett Sloane, Vivi Janiss The Last Flight 02/05/60 Kenneth Haigh, Simon Scott The Purple Testament 02/12/60 William Reynolds, Dick York Elegy 02/19/60 Cecil Kellaway, Jeff Morrow, Kevin Hagen Mirror Image 02/26/60 Vera Miles, Martin Milner The Monsters Are Due on Maple St 03/04/60 Claude Atkins, Barry Atwater, Jack Weston A World of Difference 03/11/60 Howard Duff, Eileen Ryan, David White Long Live Walter Jameson 03/18/60 Kevin McCarthy, Estelle Winwood People Are Alike All Over 03/25/60 Roddy McDowall, Susan Oliver The Twilight Zone Checklist SEASON ONE - continued Episode Aired Stars UUU Execution 04/01/60 Albert Salmi, Russell Johnson The Big Tall Wish 04/08/60 Ivan Dixon, Steven Perry A Nice Place to Visit 04/15/60 Larry Blyden, Sebastien Cabot Nightmare as a Child 04/29/60 Janice Rule, Terry Burnham A Stop at Willoughby 05/06/60 James Daly, Howard Smith The Chaser 05/13/60 George Grizzard, John McIntire A Passage for Trumpet 05/20/60 Jack Klugman, Mary Webster Mr. -

La Zona Del Crepuscolo Di Aleksandar Mickovic E Marcello Rossi

La zona del crepuscolo di Aleksandar Mickovic e Marcello Rossi Dal 1959, intere generazioni di telespettatori sono rimaste affascinate, terrorizzate o semplicemente conquistate dalle trame di una delle più memorabili serie televisive mai realizzate: Ai c i i r t (The Twilight Zone, 1959-1964). Nei suoi 156 episodi non vengono narrate le vicende di un gruppo di personaggi che puntata dopo puntata vivono avventure simili tra loro, ma una varietà di semplici storie che attendono di essere raccontate... o vissute i i i r t è infatti una serie antologica, senza personaggi e interpreti fissi, in ui g i pis i r hiu u st ri mp t L‟u i pu t i ri rim t st t è u distinto signore con una sottile cravatta nera, con il compito di introdurre gli spettatori nella zona r pus : R S r i g M S r i g r s t t ‟ spit s ri ; g i è st t i r t r , ‟ ut r pri ip i pr utt r i i i r t debuttò sugli schermi statunitensi il 2 ottobre 1959, ma la sua storia inizia ben due anni prima, quando Rod Serling, un affermato sceneggiatore televisivo, ultimò il pi p r u p ssibi pis i pi t i tit t “Th Tim E m t” Serling aveva iniziato a scrivere prima per la radio e poi per la televisione già ai tempi dei suoi stu i g , si r r pi m t gu g t u ‟ ttim r put zi N 1958, ‟ t i 33 i, v iv r t ‟Emmy w r (g i Os r p r t visi ) p r t rz v t S r i g aveva dimostrato di essere uno scrittore di talento soprattutto nel genere drammatico; aveva raggiunto sia il successo artistico che quello finanziario. -

'Why?': Contested Concepts of Ultimacy In

Generation ‘Why?’: Contested Concepts of Ultimacy in Contemporary Western European Culture Pieter Cammeraat, BA (Hons.) Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for an MA in Religious Studies at the Department of Humanities and Languages, College of Tourism and Arts, Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology Supervisor of Research Barry McMillan, STL Supervision Mentor Dr Pauline Logue Collins I, hereby, declare that this is my own work. …………………………………………………………….. Submitted to the Higher Education and Training Awards Council 2012 Table of Contents Acknowledgements i Abstract ii Introduction 3 0.1 Introduction 4 0.2 Background of Author 5 0.3 Culture 5 0.4 Contemporary Western European Culture 6 0.5 Image, Imagination, and Ultimacy 8 0.6 Contrasting ‘Languages’ 10 0.7 The Foundations of the Christian Weltanschauung: Grace and Revelation 11 Chapter One: Critiquing Contemporary Western European Culture 13 1.1 Introduction 14 1.2 Culture 14 1.3 Communicated Meanings 18 1.4 Contemporary Western European Culture 22 1.5 The Generation Title 24 1.6 The Connected World 26 1.7 Tools for Communication 30 1.7.1 Television 30 1.7.2 Constructionism and Television 33 1.7.3 The Internet 36 1.8 Advertising Transcendence 41 1.9 Conclusion 50 Chapter Two: Questions of Meaning and Ultimacy 53 2.1 Introduction 54 2.2 ‘Language’ and the Cultural Universe 55 2.3 ‘Language’ and Consciousness 56 2.4 The Potency of Imagery 60 2.5 ‘Language’ and Concepts of Reality 64 2.6 Reality and Ideology 67 2.7 Lived Experience and the Formation of Imagination 73 2.8 Imagination, -

University of Nevada, Reno Between the Pit of Man's Fears and The

University of Nevada, Reno Between the Pit of Man’s Fears and the Summit of his Knowledge: Rethinking Masculine Paradigms in Postwar America via Television’s The Twilight Zone A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by Erin Kathleen Cummings Dr. C. Elizabeth Raymond/Thesis Advisor August 2011 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by ERIN KATHLEEN CUMMINGS entitled Between the Pit of Man’s Fears and the Summit of his Knowledge: Rethinking Masculine Paradigms in Postwar America via Television’s The Twilight Zone be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Advisor Alicia Barber, Ph.D., Committee Member Dennis Dworkin, Ph.D., Committee Member Stacey Burton, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative Marsha H. Read, Ph. D., Dean, Graduate School August, 2011 i Abstract During the opening credits of the first season of The Twilight Zone, Rod Serling defined the Twilight Zone as another dimension located “between the pit of man’s fears and the summit of his knowledge.” Serling’s creative commentary theoretically speaks to the process through which gender paradigms have been constructed and transformed over time. As Gail Bederman explains in Manliness and Civilization (1995), gender construction is a historical, dynamic process in which men and women actively transform gender ideals by blending, adapting, and renegotiating older models in conjunction with concurrent modes. Between the summit of knowledge (that which is known) and the pit of fear (that which is unknown) gender is indeed constructed.