U.S. Special Operations Forces in the Philippines, 2001-2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

Philippine Election ; PDF Copied from The

Senatorial Candidates’ Matrices Philippine Election 2010 Name: Nereus “Neric” O. Acosta Jr. Political Party: Liberal Party Agenda Public Service Professional Record Four Pillar Platform: Environment Representative, 1st District of Bukidnon – 1998-2001, 2001-2004, Livelihood 2004-2007 Justice Provincial Board Member, Bukidnon – 1995-1998 Peace Project Director, Bukidnon Integrated Network of Home Industries, Inc. (BINHI) – 1995 seek more decentralization of power and resources to local Staff Researcher, Committee on International Economic Policy of communities and governments (with corresponding performance Representative Ramon Bagatsing – 1989 audits and accountability mechanisms) Academician, Political Scientist greater fiscal discipline in the management and utilization of resources (budget reform, bureaucratic streamlining for prioritization and improved efficiencies) more effective delivery of basic services by agencies of government. Website: www.nericacosta2010.com TRACK RECORD On Asset Reform and CARPER -supports the claims of the Sumilao farmers to their right to the land under the agrarian reform program -was Project Director of BINHI, a rural development NGO, specifically its project on Grameen Banking or microcredit and livelihood assistance programs for poor women in the Bukidnon countryside called the On Social Services and Safety Barangay Unified Livelihood Investments through Grameen Banking or BULIG Nets -to date, the BULIG project has grown to serve over 7,000 women in 150 barangays or villages in Bukidnon, -

Taking Peace Into Their Own Hands

Taking Peace into An External Evaluation of the Tumikang Sama Sama of Sulu, Philippinestheir own Hands August 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD Centre) would like to thank the author of this report, Marides Gardiola, for spending time in Sulu with our local partners and helping us capture the hidden narratives of their triumphs and challenges at mediating clan confl icts. The HD Centre would also like to thank those who have contributed to this evaluation during the focused group discussions and interviews in Zamboanga and Sulu. Our gratitude also goes to Mary Louise Castillo who edited the report, Merlie B. Mendoza for interviewing and writing the profi le of the 5 women mediators featured here, and most especially to the Delegation of the European Union in the Philippines, headed by His Excellency Ambassador Guy Ledoux, for believing in the power of local suluanons in resolving their own confl icts. Lastly, our admiration goes to the Tausugs for believing in the transformative power of dialogue. DISCLAIMER This publication is based on the independent evaluation commissioned by the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue with funding support from the Delegation of the European Union in the Philippines. The claims and assertions in the report are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily refl ect the offi cial position of the HD Centre nor of the Eurpean Union. COVER “Taking Peace Into Their Own Hands” expresses how people in the midst of confl ict have taken it upon themselves to transform their situation and usher in relative peace. The cover photo captures the culmination of the mediation process facilitated by the Tumikang Sama Sama along with its partners from the Provincial Government, the Municipal Governments of Panglima Estino and Kalinggalan Caluang, the police and the Marines. -

Sopkin to Lead '49 Drive; UJA Caravan Train Here

----- ·empl e Bt: th- EL. Broad & Gl cnh~m St$. Only An51lo-Jewi1h Serving 30,000 Newspaper in This State in Rhode Island VOL. XXXIV, NO. 5 FRIDAY, APRIL 8, 1949 PROVIDENCE. R. I . TWENTY-FOUR PAGES 7 CENTS THE COPY Sopkin to Lead '49 Drive; UJA Caravan Train Here Li'I Abner Creator, Miss America Here Sun. Speakers ·Stress Capacity Crowd Need of U. S. Aid Attends Rally The a ppointment of Alvin A. j know that you will not refuse. Sopkin as chairman of the 1949 ; ' "We have it within our power fund-ra ising campa ign of the I to make "Homecoming-1949" the General J ewish Committee of realization of our dreams and Providence was announced Tues hopes of the past decade." day during the visit of the "Cara- I Economy In Danger van of Hope" train to this city. The need of United States aid This will m ark the fifth straight i to Israel and the DP's was the year that Sopkin has headed the keynote of the addresses delivered GJC's annual drive, which will by the speakers at Tuesday even start on Labor Day. ing's rally. Max Lerner, noted In his acceptance address, made columnist , author and lecturer, Tuesd ay evening at the Rhode told the packed throng that the Island School of Design auditor DP camps of Europe must be ium, where the "Caravan of Hope" e m p t i e d this year. Terming program was held before a capa Europe a cemetery, Lerner asserted city audience, Sopkin urged all , that if we fail to get the DP's contributors to the 1948 campaign f out of the camps, "their blood to pay their pledges at once, in I ALVIN A. -

China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States

Order Code RL32688 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States Updated April 4, 2006 Bruce Vaughn (Coordinator) Analyst in Southeast and South Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Wayne M. Morrison Specialist in International Trade and Finance Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States Summary Southeast Asia has been considered by some to be a region of relatively low priority in U.S. foreign and security policy. The war against terror has changed that and brought renewed U.S. attention to Southeast Asia, especially to countries afflicted by Islamic radicalism. To some, this renewed focus, driven by the war against terror, has come at the expense of attention to other key regional issues such as China’s rapidly expanding engagement with the region. Some fear that rising Chinese influence in Southeast Asia has come at the expense of U.S. ties with the region, while others view Beijing’s increasing regional influence as largely a natural consequence of China’s economic dynamism. China’s developing relationship with Southeast Asia is undergoing a significant shift. This will likely have implications for United States’ interests in the region. While the United States has been focused on Iraq and Afghanistan, China has been evolving its external engagement with its neighbors, particularly in Southeast Asia. In the 1990s, China was perceived as a threat to its Southeast Asian neighbors in part due to its conflicting territorial claims over the South China Sea and past support of communist insurgency. -

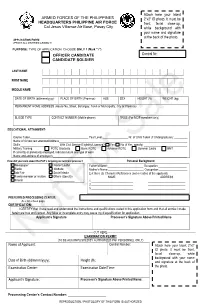

Examination Date/Time: Applicant's Signature

Attach here your latest ARMED FORCES OF THE PHILIPPINES 2”x2” ID photo. It must be HEADQUARTERS PHILIPPINE AIR FORCE front, facial close-up, Col Jesus Villamor Air Base, Pasay City white background with your name and signature at the back of the photo. APPLICATION FORM (PRINT ALL ENTRIES LEGIBLY) PURPOSE: TYPE OF APPLICATION. CHOOSE ONLY 1 (Mark “√”) Control Nr: OFFICER CANDIDATE CANDIDATE SOLDIER LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME DATE OF BIRTH (dd/mmm/yyyy) PLACE OF BIRTH (Province) AGE SEX HEIGHT (ft) WEIGHT (kg) PERMANENT HOME ADDRESS (House No.,Street, Barangay, Town or Municipality, City or Province) BLOOD TYPE CONTACT NUMBER (Mobile phone) TRIBE (For NCIP members only) EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT: Course Taken_______________________________________ Year Level _________________ Nr. of Units Taken (if Undergraduate): _________ Name of School last attended/Address______________________________________________________________________________________ Skill/s__________________________ With Civil Service Eligibility/Licensed? Yes No (if Yes, specify) _____________________________ Military Training: POTC Graduate Basic ROTC Advance ROTC Summer Cadre BMT If currently or previously employed, indicate nature and type of work_______________________________________________________________ Name and address of employer/s__________________________________________________________________________________________ How did you learn about the PAF’s ongoing recruitment process? Personal Background Newspaper Poster/Leaflet Father’s Name:________________________ -

Assessment of Impediments to Urban-Rural Connectivity in Cdi Cities

ASSESSMENT OF IMPEDIMENTS TO URBAN-RURAL CONNECTIVITY IN CDI CITIES Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project CONTRACT NO. AID-492-H-15-00001 JANUARY 27, 2017 This report is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the International City/County Management Association (ICMA) and do not necessarily reflect the view of USAID or the United States Agency for International Development USAID Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project Page i Pre-Feasibility Study for the Upgrading of the Tagbilaran City Slaughterhouse ASSESSMENT OF IMPEDIMENTS TO URBAN-RURAL CONNECTIVITY IN CDI CITIES Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project CONTRACT NO. AID-492-H-15-00001 Program Title: USAID/SURGE Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Philippines Contract Number: AID-492-H-15-00001 Contractor: International City/County Management Association (ICMA) Date of Publication: January 27, 2017 USAID Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project Page ii Assessment of Impediments to Urban-Rural Connectivity in CDI Cities Contents I. Executive Summary 1 II. Introduction 7 II. Methodology 9 A. Research Methods 9 B. Diagnostic Tool to Assess Urban-Rural Connectivity 9 III. City Assessments and Recommendations 14 A. Batangas City 14 B. Puerto Princesa City 26 C. Iloilo City 40 D. Tagbilaran City 50 E. Cagayan de Oro City 66 F. Zamboanga City 79 Tables Table 1. Schedule of Assessments Conducted in CDI Cities 9 Table 2. Cargo Throughput at the Batangas Seaport, in metric tons (2015 data) 15 Table 3. -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AURORA

2010 Census of Population and Housing Aurora Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AURORA 201,233 BALER (Capital) 36,010 Barangay I (Pob.) 717 Barangay II (Pob.) 374 Barangay III (Pob.) 434 Barangay IV (Pob.) 389 Barangay V (Pob.) 1,662 Buhangin 5,057 Calabuanan 3,221 Obligacion 1,135 Pingit 4,989 Reserva 4,064 Sabang 4,829 Suclayin 5,923 Zabali 3,216 CASIGURAN 23,865 Barangay 1 (Pob.) 799 Barangay 2 (Pob.) 665 Barangay 3 (Pob.) 257 Barangay 4 (Pob.) 302 Barangay 5 (Pob.) 432 Barangay 6 (Pob.) 310 Barangay 7 (Pob.) 278 Barangay 8 (Pob.) 601 Calabgan 496 Calangcuasan 1,099 Calantas 1,799 Culat 630 Dibet 971 Esperanza 458 Lual 1,482 Marikit 609 Tabas 1,007 Tinib 765 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Aurora Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Bianuan 3,440 Cozo 1,618 Dibacong 2,374 Ditinagyan 587 Esteves 1,786 San Ildefonso 1,100 DILASAG 15,683 Diagyan 2,537 Dicabasan 677 Dilaguidi 1,015 Dimaseset 1,408 Diniog 2,331 Lawang 379 Maligaya (Pob.) 1,801 Manggitahan 1,760 Masagana (Pob.) 1,822 Ura 712 Esperanza 1,241 DINALUNGAN 10,988 Abuleg 1,190 Zone I (Pob.) 1,866 Zone II (Pob.) 1,653 Nipoo (Bulo) 896 Dibaraybay 1,283 Ditawini 686 Mapalad 812 Paleg 971 Simbahan 1,631 DINGALAN 23,554 Aplaya 1,619 Butas Na Bato 813 Cabog (Matawe) 3,090 Caragsacan 2,729 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and -

The Humanitarian Impact of Drones

THE HUMANITARIAN IMPACT OF DRONES The Humanitarian Impact of Drones 1 THE HUMANITARIAN IMPACT OF DRONES THE HUMANITARIAN IMPACT OF DRONES © 2017 Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom; International Contents Disarmament Institute, Pace University; Article 36. October 2017 The Humanitarian Impact of Drones 1st edition 160 pp 3 Preface Permission is granted for non-commercial reproduction, Cristof Heyns copying, distribution, and transmission of this publication or parts thereof so long as full credit is given to the 6 Introduction organisation and author; the text is not altered, Ray Acheson, Matthew Bolton, transformed, or built upon; and for any reuse or distribution, these terms are made clear to others. and Elizabeth Minor Edited by Ray Acheson, Matthew Bolton, Elizabeth Minor, and Allison Pytlak. Impacts Thank you to all authors for their contributions. 1. Humanitarian Harm This publication is supported in part by a grant from the 15 Foundation Open Society Institute in cooperation with the Jessica Purkiss and Jack Serle Human Rights Initiative of the Open Society Foundations. Cover photography: 24 Country case study: Yemen ©2017 Kristie L. Kulp Taha Yaseen 29 2. Environmental Harm Doug Weir and Elizabeth Minor 35 Country case study: Nigeria Joy Onyesoh 36 3. Psychological Harm Radidja Nemar 48 4. Harm to Global Peace and Security Chris Cole 58 Country case study: Djibouti Ray Acheson 64 Country case study: The Philippines Mitzi Austero and Alfredo Ferrariz Lubang 2 1 THE HUMANITARIAN IMPACT OF DRONES Preface Christof Heyns 68 5. Harm to Governmental It is not difficult to understand the appeal of Transparency Christof Heyns is Professor of Law at the armed drones to those engaged in war and other University of Pretoria. -

DND, DPWH Start Construction of More Infra Projects

Date Released: 24 June 2021 Releasing Officer: DIR. ARSENIO R. ANDOLONG Chief, Defense Communications Service DND, DPWH start construction of more infra projects Representing the Secretary of National Defense, Secretary Delfin N Lorenzana, the DND TIKAS Champion, Defense Undersecretary Reynaldo B Mapagu together with DPWH Secretary Mark Villar attended the virtual ground breaking ceremonies for the construction of Barracks with Parking Way located at the Naval Station Felix Apolinario, Panacan, Davao City and the blessing and inauguration of the Six-Story Academic Building of the PA Intelligence Center of Excellence, Army Intelligence Regiment (PAICOE, AIR) located at Fort Andres Bonifacio, Metro Manila. They also witnessed the ceremonial signing and turn-over of documents for the Academic Building of the PAICOE, AIR between Col Yegor Rey Barroquillo, Regiment Commander, AIR and Engr. Medel Chua, District Engineer, Metro Manila 1st District Engineering Office, DPWH. The two projects are part of the DND-DPWH TIKAS Program aimed at addressing the various facility requirements of different AFP units across the country. The Academic Building of the PAICOE, AIR, is just one of the tangible accomplishments under the TIKAS Program. Previously, Sec Lorenzana and Sec Villar have inaugurated other completed TIKAS projects such as the new Camp Aguinaldo Station Hospital in Camp Aguinaldo, Quezon City; Admin Building and Headquarters of the 7th Infantry Division in Fort Magsaysay, Nueva Ecija; and, the various infrastructure projects for Training and Doctrine Command, PA in Camp O'Donnell, Capas, Tarlac. In the message of Secretary Lorenzana, delivered by Usec Mapagu, Sec Lorenzana expressed the profound appreciation and gratitude of the One Defense Team for the continuous support of the DPWH under the leadership of Sec Villar in the implementation of various peace and security infrastructure projects for the AFP. -

Counter-Insurgency Vs. Counter-Terrorism in Mindanao

THE PHILIPPINES: COUNTER-INSURGENCY VS. COUNTER-TERRORISM IN MINDANAO Asia Report N°152 – 14 May 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. ISLANDS, FACTIONS AND ALLIANCES ................................................................ 3 III. AHJAG: A MECHANISM THAT WORKED .......................................................... 10 IV. BALIKATAN AND OPLAN ULTIMATUM............................................................. 12 A. EARLY SUCCESSES..............................................................................................................12 B. BREAKDOWN ......................................................................................................................14 C. THE APRIL WAR .................................................................................................................15 V. COLLUSION AND COOPERATION ....................................................................... 16 A. THE AL-BARKA INCIDENT: JUNE 2007................................................................................17 B. THE IPIL INCIDENT: FEBRUARY 2008 ..................................................................................18 C. THE MANY DEATHS OF DULMATIN......................................................................................18 D. THE GEOGRAPHICAL REACH OF TERRORISM IN MINDANAO ................................................19 -

ADDRESSING ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE in the PHILIPPINES PHILIPPINES Second-Largest Archipelago in the World Comprising 7,641 Islands

ADDRESSING ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE IN THE PHILIPPINES PHILIPPINES Second-largest archipelago in the world comprising 7,641 islands Current population is 100 million, but projected to reach 125 million by 2030; most people, particularly the poor, depend on biodiversity 114 species of amphibians 240 Protected Areas 228 Key Biodiversity Areas 342 species of reptiles, 68% are endemic One of only 17 mega-diverse countries for harboring wildlife species found 4th most important nowhere else in the world country in bird endemism with 695 species More than 52,177 (195 endemic and described species, half 126 restricted range) of which are endemic 5th in the world in terms of total plant species, half of which are endemic Home to 5 of 7 known marine turtle species in the world green, hawksbill, olive ridley, loggerhead, and leatherback turtles ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE The value of Illegal Wildlife Trade (IWT) is estimated at $10 billion–$23 billion per year, making wildlife crime the fourth most lucrative illegal business after narcotics, human trafficking, and arms. The Philippines is a consumer, source, and transit point for IWT, threatening endemic species populations, economic development, and biodiversity. The country has been a party to the Convention on Biological Diversity since 1992. The value of IWT in the Philippines is estimated at ₱50 billion a year (roughly equivalent to $1billion), which includes the market value of wildlife and its resources, their ecological role and value, damage to habitats incurred during poaching, and loss in potential