0415970342.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Savoy and Regent Label Discography

Discography of the Savoy/Regent and Associated Labels Savoy was formed in Newark New Jersey in 1942 by Herman Lubinsky and Fred Mendelsohn. Lubinsky acquired Mendelsohn’s interest in June 1949. Mendelsohn continued as producer for years afterward. Savoy recorded jazz, R&B, blues, gospel and classical. The head of sales was Hy Siegel. Production was by Ralph Bass, Ozzie Cadena, Leroy Kirkland, Lee Magid, Fred Mendelsohn, Teddy Reig and Gus Statiras. The subsidiary Regent was extablished in 1948. Regent recorded the same types of music that Savoy did but later in its operation it became Savoy’s budget label. The Gospel label was formed in Newark NJ in 1958 and recorded and released gospel music. The Sharp label was formed in Newark NJ in 1959 and released R&B and gospel music. The Dee Gee label was started in Detroit Michigan in 1951 by Dizzy Gillespie and Divid Usher. Dee Gee recorded jazz, R&B, and popular music. The label was acquired by Savoy records in the late 1950’s and moved to Newark NJ. The Signal label was formed in 1956 by Jules Colomby, Harold Goldberg and Don Schlitten in New York City. The label recorded jazz and was acquired by Savoy in the late 1950’s. There were no releases on Signal after being bought by Savoy. The Savoy and associated label discography was compiled using our record collections, Schwann Catalogs from 1949 to 1982, a Phono-Log from 1963. Some album numbers and all unissued album information is from “The Savoy Label Discography” by Michel Ruppli. -

Univeristy of California Santa Cruz Cultural Memory And

UNIVERISTY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ CULTURAL MEMORY AND COLLECTIVITY IN MUSIC FROM THE 1991 PERSIAN GULF WAR A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in MUSIC by Jessica Rose Loranger December 2015 The Dissertation of Jessica Rose Loranger is approved: ______________________________ Professor Leta E. Miller, chair ______________________________ Professor Amy C. Beal ______________________________ Professor Ben Leeds Carson ______________________________ Professor Dard Neuman ______________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Jessica Rose Loranger 2015 CONTENTS Illustrations vi Musical Examples vii Tables viii Abstract ix Acknowledgments xi CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 Purpose Literature, Theoretical Framework, and Terminology Scope and Limitations CHAPTER 2: BACKGROUND AND BUILDUP TO THE PERSIAN GULF WAR 15 Historical Roots Desert Shield and Desert Storm The Rhetoric of Collective Memory Remembering Vietnam The Antiwar Movement Conclusion CHAPTER 3: POPULAR MUSIC, POPULAR MEMORY 56 PART I “The Desert Ain’t Vietnam” “From a Distance” iii George Michael and Styx Creating Camaraderie: Patriotism, Country Music, and Group Singing PART II Ice-T and Lollapalooza Michael Franti Ani DiFranco Bad Religion Fugazi Conclusion CHAPTER 4: PERSIAN GULF WAR SONG COLLECTION, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 116 Yellow Ribbons: Symbols and Symptoms of Cultural Memory Parents and Children The American Way Hussein and Hitler Antiwar/Peace Songs Collective -

Extra Special Supplement to the Great R&B Files Includes Updated

The Great R&B Pioneers Extra Special Supplement to the Great R&B Files 2020 The R&B Pioneers Series edited by Claus Röhnisch Extra Special Supplement to the Great R&B Files - page 1 The Great R&B Pioneers Is this the Top Ten ”Super Chart” of R&B Hits? Ranking decesions based on information from Big Al Pavlow’s, Joel Whitburn’s, and Bill Daniels’ popularity R&B Charts from the time of their original release, and the editor’s (of this work) studies of the songs’ capabilities to ”hold” in quality, to endure the test of time, and have ”improved” to became ”classic representatives” of the era (you sure may have your own thoughts about this, but take it as some kind of subjective opinion - with a serious try of objectivity). Note: Songs listed in order of issue date, not in ranking order. Host: Roy Brown - ”Good Rocking Tonight” (DeLuxe) 1947 (youtube links) 1943 Don’t Cry, Baby (Bluebird) - Erskine Hawkins and his Orchestra Vocal refrain by Jimmy Mitchell (sic) Written by Saul Bernie, James P. Johnson and Stella Unger (sometimes listed as by Erskine Hawkins or Jmmy Mitchelle with arranger Sammy Lowe). Originally recorded by Bessie Smith in 1929. Jimmy 1. Mitchell actually was named Mitchelle and was Hawkins’ alto sax player. Brothers Paul (tenorsax) and Dud Bascomb (trumpet) played with Hawkins on this. A relaxed piano gives extra smoothness to it. Erskine was a very successful Hawkins was born in Birmingham, Alabama. Savoy Ballroom ”resident” bandleader and played trumpet. in New York for many years. -

Bakalářská Práce

JANÁČKOVA AKADEMIE MÚZICKÝCH UMĚNÍ V BRNĚ Hudební fakulta Katedra zpěvu Gospelová hudba Magisterská práce Autor práce: BcA. Jana Melišková Vedoucí práce: odb. as. MgA. Jan Dalecký Oponent práce: PhDr. Alena Borková Brno 2015 „A potom hovoril: Mužovia izraelskí, dobre si rozvážte, čo urobiť s týmito ľuďmi. Lebo pred nedávnom povstal Teudas, ktorý sa vydával za nejakého veľkého, a pripojilo sa k nemu asi štyristo mužov. Ale ho zabili a všetci, ktorí ho poslúchali, sa rozpŕchli a vyšli navnivoč. Po ňom, v dňoch popisu, povstal Judáš Galilejský a strhol so sebou ľud; aj on zahynul a všetci, ktorí ho poslúchali, boli rozprášení. Preto vám teraz hovorím: Dajte pokoj týmto ľuďom a nechajte ich. Lebo ak je z ľudí táto rada alebo toto dielo, rozpadne sa;ak je však z Boha, nebudete ich môcť zahubiť. Aby sa nedokázalo, že bojujete aj proti Bohu.“ Sk 5, 35-39 Bibliografický záznam MELIŠKOVÁ, Jana. Gospelová hudba [Gospel Music]. Brno. Janáčkova akademie múzických umění v Brně, Hudební fakulta, Katedra zpěvu, 2015. s. 98. Vedoucí Magisterské práce odb. as. MgA. Jan Dalecký. Anotácia Magisterská práca „Gospelová hudba“ pojednáva o vzniku, histórii a vývoji gospelovej hudby na území Ameriky a jej rozšírení do ostatných oblastí sveta. V kontexte krátko predstavuje dôležité osobnosti gospelu a ich význam pre vývoj a bohatosť gospelovej hudby. Stručne se zaoberá hudobne-teoretickými špecifikami a žánrovým rozdelením tejto hudby. Annotation Diploma thesis „Gospel Music” deals with the origin, history and evolution of gospel music in America and its expansion to other areas of the world. Presents important figures of gospel and their importance for the development and richness of gospel music and deals briefly with musical-theoretical specifics and genre division of this music. -

諾箋護憲薫葦嵩叢 Br皿ant Years of Singing Pure Gospel with the Soul Stirrers, The

OCk and ro11 has always been a hybrid music, and before 1950, the most important hybrids pop were interracial. Black music was in- 恥m `しfluenced by white sounds (the Ink Spots, Ravens and Orioles with their sentimental ballads) and white music was intertwined with black (Bob Wills, Hank Williams and two generations of the honky-tOnk blues). ,Rky血皿and gQ?pel, the first great hy垣i立垂a血QnPf †he囲fti鎧T臆ha陣erled within black Though this hybrid produced a dutch of hits in the R&B market in the early Fifties, Only the most adventurous white fans felt its impact at the time; the rest had to wait for the comlng Of soul music in the Sixties to feel the rush of rock and ro11 sung gospel-Style. くくRhythm and gospel’’was never so called in its day: the word "gospel,, was not something one talked about in the context of such salacious songs as ’くHoney Love’’or ”Work with Me Annie.’’Yet these records, and others by groups like theeBQ聖二_ inoes-and the Drif曲 閣閣閣議竪醒語間監護圏監 Brown, Otis Redding and Wilson Pickett. Clyde McPhatter, One Of the sweetest voices of the Fifties. Originally a member of Billy Ward’s The combination of gospel singing with the risqu6 1yrics Dominoes, he became the lead singer of the original Drifters, and then went on to pop success as a soIoist (‘くA I.over’s Question,’’ (、I.over Please”). 諾箋護憲薫葦嵩叢 br皿ant years of singing pure gospel with the Soul Stirrers, the resulting schism among Cooke’s fans was deeper and longer lasting than the divisions among Bob Dylan’s partisans after he went electric in 1965. -

Charles Taylor

“God’s Got The Keys”: Three Legendary Black Pianists From Gospel’s Golden Age” Herbert “Pee Wee” Pickard, Evelyn Starks Hardy & Prof. Charles Taylor Compiled and annotated by Opal Louis Nations BISHOP CHARLES TAYLOR Percussive accompaniment within the black church experience dates back to the early part of the century. Both the Pentecostal and Holiness denominations required a measure of celebratory music to heighten their sometimes wildly ecstatic song services. First came the instruments commonly associated with minstrelsy, the banjo, harmonium and melodium, then gradually the piano became the favored instrument. One of the earliest exponents was Blind Arizona Dranes (c.1905-c.1960), a female sanctified singer and first-known gospel-pianist. Dranes served as songleader and pianist for Bishops Emmett Morey Page (1871-1944), Riley Felman Williams (c.1880-1952) and Samuel M. Crouch Jr. (1896-1976). Dranes played in the ragtime tradition synonymous with the syncopated styles that flourished in the 1890s. Dranes recorded with Sarah Martin in Chicago for Okeh Records. Then came Thomas Andrew Dorsey, known as “The Father of Gospel Music,” who took the straight forward blues refrain and together with his simple, spiritual propensity developed a style that became known as gospel piano. Dorsey, who had started out as arranger and band leader for the great Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, went on to write many jazz and blues compositions for Tampa Red (Hudson Whittaker) and for his own small ensemble, Texas Tommy & Friends. One of Dorsey’s earliest gospel compositions, “If I don’t get there,” was published in 1921 in “Gospel Pearls,” a songbook published by the newly formed National Baptist Convention. -

Guide to the Martin and Morris Music Company Records, Circa 1930-1985

Guide to the Martin and Morris Music Company Records, circa 1930-1985 NMAH.AC.0492 Deborra Richardson March 1996 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 5 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Correspondence, 1941-1980.................................................................... 6 Series 2: Business and Financial Records, 1940-1978........................................... 8 Series 3: Sheet Music, circa 1930-1985................................................................ 11 Series 4: Song Books, ca. 1930-1985.................................................................. -

Ice-T Home Invasion Mp3, Flac, Wma

Ice-T Home Invasion mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Home Invasion Country: UK & Europe Style: Gangsta MP3 version RAR size: 1766 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1173 mb WMA version RAR size: 1539 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 898 Other Formats: DTS FLAC WMA MOD AHX AIFF MP4 Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Warning 0:36 2 It's On 4:56 3 Ice M.F. T 3:41 4 Home Invasion 2:59 G Style 5 4:29 Producer – Hen Gee*, DJ L.P.* 6 Addicted To Danger 3:27 7 Question And Answer 0:33 8 Watch The Ice Break 4:24 Race War 9 4:50 Bass – Mooseman (Body Count)* 10 That's How I'm Livin' 4:39 11 I Ain't New Ta This 5:01 Pimp Behind The Wheels (DJ Evil E The Great) 12 5:04 Producer – Hen Gee*, DJ L.P.* Gotta Lotta Love 13 5:24 Producer – Donald D Hit The Fan 14 4:47 Producer – Trekan Depths Of Hell 15 5:15 Bass – Mooseman (Body Count)*Featuring – Daddy Nitro 99 Problems 16 4:50 Featuring – Brother Marquis Funky Gripsta 17 4:47 Lyrics By – Grip*Music By – DJ Aladdin, Ice-TProducer, Written-By – Grip*, Wolf 18 Message To The Soldier 5:36 19 Ain't A Damn Thing Changed 0:36 Companies, etc. Recorded At – Soundcastle Recorded At – Syndicate Studios West Recorded At – Conway Studios Mixed At – Soundcastle Mastered At – Future Disc Copyright (c) – Rhyme $yndicate Records Phonographic Copyright (p) – Rhyme $yndicate Records Published By – Warner Chappell Music Publishing Published By – Ammo Dump Music Credits Design [Lp] – Dirk Walter Design Concept [Lp Cover] – David Halili*, Ice-T Engineer – Tony Pizarro Engineer [Assistant] – Kev D Executive Producer – Ice-T -

Exploring the Gospel Fusion Arrangements of the Recording Collective

Belmont University Belmont Digital Repository Composition/Recording Projects School of Music Fall 11-20-2020 Exploring the Gospel Fusion Arrangements of The Recording Collective Tyler Williams [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.belmont.edu/music_comp Part of the Composition Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Williams, Tyler, "Exploring the Gospel Fusion Arrangements of The Recording Collective" (2020). Composition/Recording Projects. 2. https://repository.belmont.edu/music_comp/2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Music at Belmont Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Composition/Recording Projects by an authorized administrator of Belmont Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXPLORING THE GOSPEL FUSION ARRANGEMENTS OF THE RECORDING COLLECTIVE By TYLER WILLIAMS A PRODUCTION PAPER Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in Commercial Music, Media Composition and Arranging in the School of Music of the College of Music and Performing Arts Belmont University NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE November 2020 Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the contributions of numerous individuals. I first want to thank Dr. Tony Moreira for being such an encouraging presence during my time here at Belmont. The fruits of his musical instruction can be seen and heard in the arrangements included in this production. Thank you also to Keith Mason and Dr. Peter Lamothe, whose seminar classes directly impacted the trajectory and execution of this project. I am deeply grateful to the musicians whose incredible talents brought pure magic to the recording process. -

ERROLL GARNER by Mimi Clar

how many of these great CONTEMPORARY ALBUMS are in your collection ROUNDS! nrT?TF N,EHAUS UCTET.^ mm C3540 Niehaus, one of the top alto men in jazz, long time leader of the Kenton sax section, stars with two swinging C3538 Red Mitchell, one of the nation's Octets featuring such famous jazzmen favorite bassists, in a swinging program as Bill Perkins, Pepper Adams, Shelly C3542 Leroy Vinnegar, a bass player who of modern jazz classics by Parker, Roll• Manne, Frank Rosolino, Mel Lewis, Jack "walks the most!" presents his first album ins, etc. New star James Clay plays tenor Montrose, Red Mitchell, Lou Levy, the as a leader. Featured on a selection of & flute, with Lorraine GelLer, piano, and late Bob Gordon, etc. standards with a walking motif ("I'll Billy Higgins, drums. Mitchell's bass solos Walk Alone," "Walkin' My Baby Back are standouts! Home," "Would You Like To Take a Walk," etc.) are Teddy Edwards, tenor, Gerald Wilson, trumpet, Victor Feldman, vibes, the late Carl Perkins, piano, and Tony Bazley, drums. You get more , %i bounce with Curtis \ CounceL5i temporary C3544 Bob Cooper's extended "Jazz Theme & Four Variations" is a major work by C3539 The Curtis Counce Group comes up a major jazzman. Side two features with some West Coast "cooking." Tasty, Coop's tenor in swinging combo perform• with plenty of funk and soul. Bassist ances (including an intriguing "Frankie Counce's group includes ace tenorman & Johnny") with Victor Feldman, Frank C3541 Vibist, pianist, drummer, composer- Harold Land, trumpeter Jack Sheldon, Rosolino, and an all-star rhythm section: arranger Feldman is the most important the late Carl Perkins on piano, and the ianist Lou Levy; Max Bennett, bass; Mel British import in the fleld of modern jazz. -

L"'" Industry Fears of Music Bootleg- Ging Via 7H3 Memel

BACKIN BOULDER A3 SUMMIT SUMMARY THE MOST TRUSTEDtAME IN RADIO ISSUE 2020 SEPTEMBER 2 1994 This Week Ed McMahon: The answer is: `Between a rock and a hard place.'" Carnac: "On commercial where is lard rock?" Ed: `YES!! You are corRECT, sirl Fio- r o -ho!" Carnac, though retired, is indeed correct. As our Rob Hend notes, metal -based music-and even the many ac:s that rare broken through-have traditionally been sadaled with miscon- ceptions and stereotypes. Classic Rock station now feat r3 many acts consid- ered too outrageous a couple of decades ago, but their contempo- rary comfieroarts re still %in- n ng up aga 1st mantras like "tom hard" and "nar- row demos." Tnis issa. it salute to tne music au tre Sixth Annual Foundations Forum, Mt Rend and Sheila Reue survey programmers and record people, iloixiinig CathyMani (top) of <ISW-Seattle, Susan Naramore (middle) of Geffen Records anc Jessica Harley (belovo cf Elektra Records on -he big questions surrounding tt-e MUSIC a -Id the format. Sacs Faulkner: don't let fear drive my musi- cal decisions.' jai ...-A In News, the fin101011111/11S, Keith and Kent, am It's got its owu initials: SOUNDGARDEN back fron another triumphant Gavin A3 sianmit in Boulder Ed :4ANTERA offer an overview. We also che,cK CORIRAWKlaud ROAR, 1 KILLING JOKE out Lollapaloota '94, note changes at RCA and Virgil Records, chat but outside of College iiir li- VACH NE HEAD with President Clinton's rockily', rollin'. radio -Min' younger half- stations, Hard Rock is brother, Roger, and report on l"'" industry fears of music bootleg- ging via 7h3 Memel. -

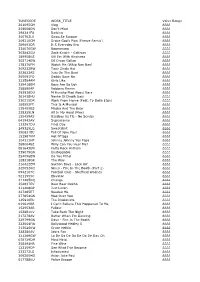

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261095CM

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261095CM Vlog ££££ 259008DN Don't Mind ££££ 298241FU Barking ££££ 300703LV Swag Se Swagat ££££ 309210CM Drake God's Plan (Freeze Remix) ££££ 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 234070GW Boomerang ££££ 302842GU Zack Knight - Galtiyan ££££ 189958KS Kill Em With Kindness ££££ 302714EW Dil Diyan Gallan ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 309232BW Tiger Zinda Hai ££££ 253823AS Juju On The Beat ££££ 265091FQ Daddy Says No ££££ 232584AM Girls Like ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 258890AP Robbery Remix ££££ 292938DU M Huncho Mad About Bars ££££ 261438HU Nashe Si Chadh Gayi ££££ 230215DR Work From Home (Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign) ££££ 188552FT This Is A Musical ££££ 135455BS Masha And The Bear ££££ 238329LN All In My Head (Flex) ££££ 155459AS Bassboy Vs Tlc - No Scrubs ££££ 041942AV Supernanny ££££ 133267DU Final Day ££££ 249325LQ Sweatshirt ££££ 290631EU Fall Of Jake Paul ££££ 153987KM Hot N*Gga ££££ 304111HP Johnny Johnny Yes Papa ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 081643EN Party Rock Anthem ££££ 239079GN Unstoppable ££££ 254096EW Do You Mind ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 216422EM Section Boyz - Lock Arf ££££ 325052KQ Nines - Fire In The Booth (Part 2) ££££ 0942107C Football Club - Sheffield Wednes ££££ 5211555C Elevator ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 254637EV Baar Baar Dekho ££££ 311408GP Just Listen ££££ 227485ET Needed Me ££££ 277854GN Mad Over You ££££ 125910EU The Illusionists ££££ 019619BR I Can't Believe This Happened To Me ££££ 152953AR Fallout ££££ 153881KV Take Back The Night ££££ 217278AV Better When