BT's Response to Ofcom's Consultation Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Annual Report

BT Group plc Annual Report & Form 20-F 2017 Welcome to BT Group plc’s Annual Report and Form-20F for 2017 Where to find more information www.btplc.com www.bt.com/annualreport Delivering our Purpose Report We’re using the power of communications to make a better world. That’s our purpose. Read our annual update. www.btplc.com/purposefulbusiness Delivering our Purpose Report Update on our progress in 2016/17 THE STRATEGIC REPORT GOVERNANCE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ADDITIONAL INFORMATION The strategic report 2 Contents Review of the year 3 How we’re organised 8 An introduction from our Chairman 10 A message from our Chief Executive 12 This is the BT Annual Report for the year ended Operating Committee 14 31 March 2017. It complies with UK regulations Our strategy Our strategy in a nutshell 16 and comprises part of the Annual Report and How we’re doing Form 20-F for the US Securities and Exchange – Delivering great customer experience 17 – Investing for growth 18 Commission to meet US regulations. – Transforming our costs 19 Key performance indicators 20 This is the third year that we’ve applied an Our business model Integrated Reporting (IR) approach to how Our business model 22 we structure and present our Annual Report. What we do 24 Resources, relationships and sustainability IR is an initiative led by the International Integrated Reporting – Financial strength 26 Council (IIRC). Its principles and aims are consistent with UK – Our people 26 regulatory developments in financial and corporate reporting. – Our networks and physical assets 30 We’ve reflected guiding principles and content elements from the – Properties 31 IIRC’s IR Framework in preparing our Annual Report. -

BT Plc Modern Slavery Act Statement 2016/17 We’Re Committed to the Principles of Ethical Behaviour and Respecting Human Rights

BT plc Modern Slavery Act Statement 2016/17 We’re committed to the principles of ethical behaviour and respecting human rights. We have a Contents long-standing policy that we don't use or accept forced, bonded or involuntary prison labour or child Our business and supply chain labour; nor do we demand deposits or hold onto our – who we are and what we do 04 workers' identity papers, or work with businesses that Our lines of business 04 do. We only work with people who choose to work Our supply chain – our suppliers and freely. We respect the right to equal opportunity, procurement process 05 freedom of association and collective bargaining. We're a signatory to the United Nations Global Value of BT supplier spend by region 05 Compact and we've committed to implementing the How we check our supply chain United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and sticks to our standards 06 Human Rights. Supplier assessments – when are they done? 06 In August 2016 we published our first Modern Slavery Act The assessment process 07 statement. This year’s statement provides an update on our progress over 2016/17 and our plans for further improvements Modern Slavery Act next year 2017/18. – mapping BT’s categories of spend 08 At a glance – what we’ve done this year: Our business operations – overview of our people and recruitment 09 Stronger governance • Our resourcing contracts now say that candidates must not be Things that matter to us 10 charged fees – the employer must pay How we make sure our people • We've doubled the number of assessors we use -

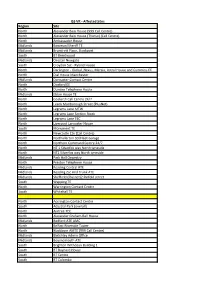

LTB 342.2019 Attachment 1

ISS VR - Affected Sites Region Site North Alexander Bain House (999 Call Centre) North Alexander Bain House (Thurso) (Call Centre) North Ambassador House Midlands Bowman/Sheriff TE Midlands Brundrett Place, Stockport South BT Brentwood Midlands Chester Newgate South Croydon Ssc - Ryland House North Darlington - Global ,Nexus, Mercia, Astral House and Cummins EE North Dial House Manchester Midlands Doncaster Contact Centre North Doxford EE North Dundee Telephone House Midlands Eldon House TE North Gosforth Call Centre 24/7 North Leeds Marlborough Street (PlusNet) North Legrams Lane MTW North Legrams Lane Section Stock North Legrams Lane TEC North Liverpool Lancaster House South Monument TE North Newcastle Cte (Call Centre) North Northallerton SD/Fleet Garage North Northern Command Centre 24/7 North NT 1 Silverfox way North tyneside North NT2 Silverfox way North tyneside Midlands Park Hall Oswestry North Preston Telephone House Midlands Reading Central ATE Midlands Reading Zsc And Trunk ATE Midlands Sheffield (Plusnet)2 Pinfold street South Wapping TE North Warrington Contact Centre South Whitehall TE North Accrington Contact Centre South Adastral Park (overall) North Aintree TEC North Alexander Graham Bell House Midlands Bedford ATE AMC North Belfast Riverside Tower North Blackburn AMTE (999 Call Centre) Midlands Bletchley Admin Office Midlands Bournemouth ATE South Brighton Withdean Building 1 South BT Baynard House South BT Centre South BT Colombo South BT Mill House South BT Tower South Canterbury Becket House South Crawley New TEC -

View Annual Report

BT ANNUAL REPORT AND FORM 20-F 2013 USER GUIDE Overview OVERVIEW Welcome to the BT Annual Report and Form 20– F 2013 . In this interactive pdf you can do many things to help you easily access the information that you want, whether that’s printing, searching for a section or website. These are explained below. Strategy 1. Document controls BUSINESS REVIEW Use the document controls located in the top right corner to help you navigate through this report. Search Print Go to Back/forward Fast link to contents one page previous page viewed Business 2. Links within this document Examples Throughout this report there are links to pages, other For further discussion of these items see pages 33 and 47 to 48. sections and web addresses for additional information. by line of business, and for the group, is provided in the table at the foot of pages 34 to 35. FINANCIAL REVIEW 3. Navigating with tabs Use the tabs to quickly go to the start of a Performance different section. Performance Governance Governance Financial statements Financial statements Additional information BT Group plc Annual Report & Form 20-F 2013 view VIEW BT Group plc Over Annual Report & OVER Form 20-F 2013 Strategy BUSINESS REVIEW Business FINANCIAL REVIEW Performance Governance BT Group plc Registered office: 81 Newgate Street, London EC1A 7AJ Registered in England and Wales No. 4190816 Produced by BT Group www.bt.com Financial statements PHME 67064 Printed in England by Pindar Scarborough Ltd Design by saslondon.com Typeset by RR Donnelley Printed on Amadeus 50 Silk which is made from 50% de-inked, post-consumer waste and 50% virgin fibre. -

(By Email) Our Ref: MGLA031218-9660 21 January

(By email) Our Ref: MGLA031218-9660 21 January 2019 Dear Thank you for your request for information which the GLA received on 3 December 2019. Your request has been dealt with under the Freedom of Information Act (2000) Our response to your request is as follows: I wish to see full copies of any and all meetings and emails with any of the following companies: InLink / LinkUK / Google / BT / Alphabet / Intersection / Primesight Regarding the InLink portals. Please find attached the information we have identified within scope of your request. Please note that some names of members of staff are exempt from disclosure under s.40 (Personal information) of the Freedom of Information Act. This information could potentially identify specific employees and as such constitutes as personal data which is defined by Article 4(1) of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) to mean any information relating to an identified or identifiable living individual. It is considered that disclosure of this information would contravene the first data protection principle under Article 5(1) of GDPR which states that Personal data must be processed lawfully, fairly and in a transparent manner in relation to the data subject. A small amount of information contained within the email of 8 November 2018 (11:48) is exempt from disclosure under the exemption for Commercial Interests at section 43(2) of the FoIA. Section 43(2) provides that information can be withheld from release if its release would, or would be likely to, prejudice the commercial interests of any person. A commercial interest relates to a person’s ability to participate competitively in a commercial activity and in this instance, the information withheld from disclosure refers price estimates for advertisement space which is not publicly available, and disclosure would compromise inlinkuk’s competitiveness in the wider out of home market. -

30 Years Movement Post-London 2012

SUPERBRANDS ANNUAL 2015 BT Achievements BT Global Services serves 87 per cent of the Brand History FTSE 100 companies and 64 per cent of the Fortune 500 companies. In the UK, BT is bt.com 1984 British Telecom is privatised, one of the largest suppliers of networked IT making it the only state-owned services for the government. telecommunications company to be privatised in Europe. International investments are helping BT’s 1991 British Telecom is restructured and corporate customers to expand into fast- relaunches as BT. growing economies across the Asia Pacific 2003 BT unveils its current corporate region, Latin America, Turkey, the Middle identity, reflecting the aspirations of a technologically innovative future. East and Africa. 2005 Following the Telecommunications BT takes corporate responsibility seriously Strategic Review, BT signs legally binding undertakings with Ofcom Market Europa League football, with exclusive live and every year at least one per cent of BT’s to help create a better regulatory BT is one of the world’s BT operates in a thriving, multi-trillion broadcast rights to all 350 matches from pre-tax profits go into programmes that framework. leading providers of pound global industry. In recent years both tournaments, for three seasons benefit the communities BT operates in. 2006 Openreach launches and is responsible the boundaries between telcos, IT from 2015/16. for managing the UK access network communications services, on behalf of the telecommunications companies, software businesses, hardware YouView is also a BT partner. This gives Recent Developments industry. serving customers in more manufacturers and broadcasters have customers a unique programme guide, BT Sport, launched in August 2013, is the 2008 BT becomes the official than 170 countries. -

British Telecommunications Plc Annual Report and Form 20-F 2003 1 Business Review

BRITISH TELECOMMUNICATIONS plc BRITISH TELECOMMUNICATIONS British Telecommunications plc Annual Report and Form 20-F 2003 2003 AND FORM 20-F REPORT ANNUAL As a wholly-owned subsidiary of BT Group plc, British Telecommunications plc meets the conditions set forth in General British Telecommunications plc Registered office: 81 Newgate Street, London EC1A 7AJ Registered in England No. 1800000 Instruction (I)(1)(a) and (b) of Form 10-K as applied to reports on Produced by BT Group Typeset by Greenaways Printed in England by Vitesse Printing Co Ltd Form 20-F and is therefore filing this Form 20-F with the reduced Printed on paper which meets international environmental standards disclosure format www.bt.com Business review 2 Financial review 6 Report of the directors 20 Statement of directors’ responsibility 22 Report of the independent auditors 23 Accounting policies 24 Consolidated financial statements 27 United States Generally Accepted Accounting Principles 70 Subsidiary undertakings, joint ventures and associates 78 Additional information for shareholders 79 Glossary of terms and US equivalents 85 Cross reference to Form 20-F 86 This is the annual report for the year ended 31 March 2003. It complies with UK regulations and is the annual report on Form 20-F for the Securities and Exchange Commission to meet US regulations. References to the “financial year” are to the year ended 31 March of each year, e.g. the “2003 financial year” refers to the year ended 31 March 2003. Unless otherwise stated, all non-financial statistics are at 31 March 2003. Please see cautionary statement regarding forward-looking statements on page 79. -

BT Group Plc Listing Particulars September 2001 Shareholders Are Advised to Read the Enclosed Documents Carefully

BT Group plc listing particulars September 2001 Shareholders are advised to read the enclosed documents carefully. If you have any queries please contact our Shareholder Helpline on Freefone 0808 100 4141 (or + 44 20 7864 9074 if you are calling from outside the UK). This helpline is available from: 8.30 a.m. to 8.30 p.m. Monday to Friday and 10.00 a.m. to 4.30 p.m. Saturdays, Sundays and UK public holidays. For legal reasons, the Shareholder Helpline will be unable to give advice on the merits of the Proposals or to provide financial advice. The Directors, whose names appear on page 8 of this document, accept responsibility for the information contained in this document. To the best of the knowledge and belief of the Directors (who have taken all reasonable care to ensure that such is the case), the information contained in this document is in accordance with the facts and does not omit anything likely to affect the import of such information. Application has been made to the UK Listing Authority for the BT Group Shares to be admitted to the Official List and to the London Stock Exchange for such BT Group Shares to be admitted to trading on the London Stock Exchange, which together, under the Listing Rules of the UK Listing Authority, will constitute official listing on a stock exchange. Subject to the passing of the Demerger Resolution, it is expected that admission of the BT Group Shares will become effective and that dealings for normal settlement will commence at 8.00 a.m. -

BT Social and Environmental Report

BT Social and Environmental Report Summary and Highlights 2005 BT Social and Environmental Report Contents – Summary and Highlights Performance snapshot 02 Employees 09 Economics 18 Chairman’s introduction 03 Investors 11 Sustainability 19 Chief Executive’s message 04 Suppliers 12 Key performance indicators Who we are 05 Community 13 and targets 20 Our approach to CSR 06 Environment 14 Hot Topics 21 Business principles 07 Digital inclusion 16 Customers 08 Human rights 17 As a communications company our aim is to help everyone benefit from improved communications. Doing this in a responsible way is what our corporate social responsibility (CSR) work is all about. BT’s Social and Environmental Report covers our policies, programmes and performance across a full range of social, environmental and economic issues, including targets for improvement.The full report is available online at www.bt.com/betterworld About our Social and Environmental Report This is a summary of our online Social and Environmental Report. It covers the financial year ending 31 March 2005. Our Social and Environmental Report is assured against the AA1000 Assurance Standard, which requires our report to reflect the interests and concerns of stakeholders. It is in accordance with the 2002 Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) guidelines. BT has been ranked as the world’s number BT is ranked third of the 132 companies one telecommunications company in the that took part. Dow Jones Sustainability Indexes for four years running. BT Social and Environmental Report Summary and Highlights 2005 01 Performance snapshot Highlights • Reviewed and improved our key performance indicators (KPIs) - Included a measure of our sickness absence rate for the • Connected 5 million UK customers to broadband – first time meeting our target a year early This helps identify health issues early so that we can We are on target to make broadband available to reduce the number of people taking time off sick. -

BT International Media Centre

Since 1989 VSC Design Ltd, has been planning, designing, installing and servicing the requirements of a rapidly changing broadcasting and media industry, delivering the highest standard of engineering BT excellence and International Media Centre customer service across a variety of technology platforms. The iconic concrete and glass circular BT Tower might be considered a piece of vintage architecture on the outside, but on the inside it plays host to a state of the 2007, VSC project managed and installed the art television facility. production and broadcast facility, a project that took four months and included bespoke The BT Tower Facilities suites designed by VSC. Originally set up as the centre point of the More recently VSC provided systems British Telecom microwave network, the 191 integration, project management and foot tower now relies on its subterranean fi bre installation for BT Media’s upgrade to a Snell optics links. With BT TV and the launch last Sirius 830 routing system and three MV-Series year of BT Sport, based at the International multi-viewers to support television outside Broadcast Centre in Stratford, the need for broadcasting (TVOB) operations for the BT an effi cient, modern facility has increased Tower facility. After the SMC, the IMC was the sharply. next step for the tower facility: a high profi le Its central London production and post- and critical business project to modernise and production hub also works with outside upgrade the outmoded centre was devised by clients, so upgrading the facilities has been VSC who successfully secured the tender. an advantage for external, as well as in-house The Brief users. -

140513 MASTER Full Draft.Docx

•••• Chapter II, Competition Act 1998 Article 102, Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union Decision of The Office of Communications CW/1103/03/13: Complaint from TalkTalk Group against BT about alleged margin squeeze in relation to superfast broadband pricing Non-confidential Issue date: 21 October 2014 Decision About this document In March 2013, Ofcom received a complaint from TalkTalk Group alleging that BT was abusing a dominant position, by operating a margin squeeze on its superfast broadband products. This document sets out Ofcom’s reasons for its decision that there are no grounds for action following its Competition Act 1998 investigation into this allegation. It explains the context of Ofcom’s decision, the facts on which Ofcom bases its decision and the legal and economic analysis that leads it to conclude that there are no grounds for action in this case. This document is a notice for the purpose of Rule 10(4) of the Competition Act 1998 (Competition and Markets Authority’s Rules) Order 2014. 1 Decision Contents Section Page 1 Executive Summary 3 2 Background 7 3 Legal framework for the investigation 27 4 BT’s position on the relevant markets 31 5 Methodology for assessment of BT’s margins 38 6 Approach to BT Sport 70 7 Results of Ofcom’s margin squeeze assessment 88 Annex Page 1 BT’s margins on superfast broadband before BT Sport 102 2 Shared costs 174 3 BT Sport ‘net costs’ 197 4 Glossary 268 2 Decision Section 1 1 Executive Summary Ofcom’s findings 1.1 This document sets out Ofcom’s reasons for its decision that there are no grounds for action in relation to its investigation of an alleged margin squeeze by BT Group plc (BT) in relation to superfast broadband (SFBB) pricing. -

Better World

Better World BT’s Social & Environment Report Contents Summary and highlights Business principles Community Customers Employees BT and the environment Suppliers CSR for investors Economics Human rights Stakeholder dialogue Sustainability BT and Digital Inclusion Data and Targets About the report Summary and highlights Better World BT’s Social & Environment Report Summary and highlights The Better World website is the BT social and environmental report. It contains a wealth of information about BT’s policies, programmes and performance across a full range of social, environmental and economic issues. It also sets out a number of targets for improvement. We publish all our social and environmental performance Chairman’s Introduction online because we believe this enables us to Our purpose is to connect the worlds of our customers communicate these impacts more effectively and engage through encouraging effective communication, irrespective in a two-way dialogue. of geography, distance, time or complexity. This summary and highlights is intended as a guide to Our industry is at the heart of society – the central the Better World site, bringing out the key points and nervous system of the modern economy and a 2 providing a flavour of the depth of content available. fundamental part of human experience. We hope it tempts you to delve further. It brings friends and families together and enables businesses and other organisations to work in partnership. Social and environmental performance This purpose is based on a social agenda and a The Better World site contains a huge amount of data commitment to inclusiveness. Our aim is to try and help about our social and environmental performance.