Maharashtra State Gazetteers: History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Siva Chhatrapati, Being a Translation of Sabhasad Bakhar with Extracts from Chitnis and Sivadigvijaya, with Notes

SIVA CHHATRAPATI Extracts and Documents relating to Maratha History Vol. I SIVA CHHATRAPATI BEING A TRANSLATION OP SABHASAD BAKHAR WITH EXTRACTS FROM CHITNIS AND SIVADIGVTJAYA, WITH NOTES. BY SURENDRANATH SEN, M.A., Premchaxd Roychand Student, Lectcrer in MarItha History, Calcutta University, Ordinary Fellow, Indian Women's University, Poona. Formerly Professor of History and English Literature, Robertson College, Jubbulpore. Published by thz UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA 1920 PRINTED BY ATCLCHANDKA BHATTACHABYYA, AT THE CALCUTTA UNIVEB8ITY PEE 88, SENATE HOUSE, CALCUTTA " WW**, #rf?fW rT, SIWiMfT, ^R^fa srre ^rtfsre wwf* Ti^vtm PREFACE The present volume is the first of a series intended for those students of Maratha history who do not know Marathi. Original materials, both published and unpublished, have been accumulating for the last sixtv years and their volume often frightens the average student. Sir Asutosh Mookerjee, therefore, suggested that a selection in a handy form should be made where all the useful documents should be in- cluded. I must confess that no historical document has found a place in the present volume, but I felt that the chronicles or bakhars could not be excluded from the present series and I began with Sabhasad bakhar leaving the documents for a subsequent volume. This is by no means the first English rendering of Sabhasad. Jagannath Lakshman Mankar translated Sabhasad more than thirty years ago from a single manuscript. The late Dr. Vincent A. Smith over- estimated the value of Mankar's work mainly because he did not know its exact nature. A glance at the catalogue of Marathi manuscripts in the British Museum might have convinced him that the original Marathi Chronicle from which Mankar translated has not been lost. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

Satara. in 1960, the North Satara Reverted to Its Original Name Satara, and South Satara Was Designated As Sangli District

MAHARASHTRA STATE GAZETTEERS Government of Maharashtra SATARA DISTRICT (REVISED EDITION) BOMBAY DIRECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT PRINTING, STATIONARY AND PUBLICATION, MAHARASHTRA STATE 1963 Contents PROLOGUE I am very glad to bring out the e-Book Edition (CD version) of the Satara District Gazetteer published by the Gazetteers Department. This CD version is a part of a scheme of preparing compact discs of earlier published District Gazetteers. Satara District Gazetteer was published in 1963. It contains authentic and useful information on several aspects of the district and is considered to be of great value to administrators, scholars and general readers. The copies of this edition are now out of stock. Considering its utility, therefore, need was felt to preserve this treasure of knowledge. In this age of modernization, information and technology have become key words. To keep pace with the changing need of hour, I have decided to bring out CD version of this edition with little statistical supplementary and some photographs. It is also made available on the website of the state government www.maharashtra.gov.in. I am sure, scholars and studious persons across the world will find this CD immensely beneficial. I am thankful to the Honourable Minister, Shri. Ashokrao Chavan (Industries and Mines, Cultural Affairs and Protocol), and the Minister of State, Shri. Rana Jagjitsinh Patil (Agriculture, Industries and Cultural Affairs), Shri. Bhushan Gagrani (Secretary, Cultural Affairs), Government of Maharashtra for being constant source of inspiration. Place: Mumbai DR. ARUNCHANDRA S. PATHAK Date :25th December, 2006 Executive Editor and Secretary Contents PREFACE THE GAZETTEER of the Bombay Presidency was originally compiled between 1874 and 1884, though the actual publication of the volumes was spread over a period of 27 years. -

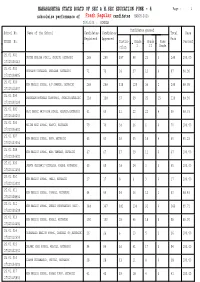

School Wise Result Statistics Report

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 1 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2020 Division : KONKAN Candidates passed School No. Name of the School Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 25.01.001 UNITED ENGLISH SCHOOL, CHIPLUN, RATNAGIRI 289 289 197 66 23 3 289 100.00 27320100143 25.01.002 SHIRGAON VIDYALAYA, SHIRGAON, RATNAGIRI 71 71 24 27 12 4 67 94.36 27320108405 25.01.003 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, A/P SAWARDE, RATNAGIRI 288 288 118 129 36 2 285 98.95 27320111507 25.01.004 PARANJAPE MOTIWALE HIGHSCHOOL, CHIPLUN,RATNAGIRI 118 118 37 39 25 15 116 98.30 27320100124 25.01.005 HAJI DAWOOD AMIN HIGH SCHOOL, KALUSTA,RATNAGIRI 61 60 11 22 22 4 59 98.33 27320100203 25.01.006 MILIND HIGH SCHOOL, RAMPUR, RATNAGIRI 70 70 38 26 6 0 70 100.00 27320106802 25.01.007 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, BHOM, RATNAGIRI 65 63 16 30 10 4 60 95.23 27320103004 25.01.008 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, MARG TAMHANE, RATNAGIRI 67 67 17 39 11 0 67 100.00 27320104602 25.01.009 JANATA MADHYAMIK VIDYALAYA, KOKARE, RATNAGIRI 65 65 38 24 3 0 65 100.00 27320112406 25.01.010 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, OMALI, RATNAGIRI 17 17 8 6 3 0 17 100.00 27320113002 25.01.011 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, POPHALI, RATNAGIRI 64 64 14 36 12 1 63 98.43 27320108904 25.01.012 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, KHERDI-CHINCHAGHARI (SATI), 348 347 181 134 31 0 346 99.71 27320101508 25.01.013 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, NIWALI, RATNAGIRI 100 100 29 46 18 6 99 99.00 27320114405 25.01.014 RATNASAGAR ENGLISH SCHOOL, DAHIWALI (B),RATNAGIRI 26 26 6 13 5 2 26 100.00 27320112604 25.01.015 DALAWAI HIGH SCHOOL, MIRJOLI, RATNAGIRI 94 94 36 41 17 0 94 100.00 27320102302 25.01.016 ADARSH VIDYAMANDIR, CHIVELI, RATNAGIRI 28 28 13 11 4 0 28 100.00 27320104303 25.01.017 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, KOSABI-FURUS, RATNAGIRI 41 41 19 18 4 0 41 100.00 27320115803 MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 2 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2020 Division : KONKAN Candidates passed School No. -

Board of College and University Development, 26

Content I. University Authorities II. Convocation III. University Adminstration IV. Schools: Campus and Sub-Centre V. Affiliated Colleges-Activites VI. List of Affiliated Colleges VII. Statistical Table Appendix 1 Editorial We are very happy to present you the annual report of Academic year 2009-2010 of Swami Ramanand Teerth Marathwada University. Education is an important instrument to enrich human mind and personality. Higher education develops the life style of common man. Therefore University and affiliated colleges are conducting many student oriented projects. The physical and qualitative development of University is the result of Hon. Vice Chancellor Dr. Sarjerao Nimse’s exceptional and outstanding leadership. We can see the change at every sphere of life which is the result of dynamic progress of science, technology and communication. Globalization has changed the traditional old methods and more opportunities. In these circumstances University updated syllabus and made more constructive and structural changes. Hon. Vice Chancellor personally thinks that overall personal development of student is more important than mare bookish merit. Therefore more fundamental facilities are being provided to the students. We believe that University is making students more perfect for the world-competation. University granted autonomy to the educational schools so that they may necessarily change syllabus whenever they need and may form more transparency in it. In this way we believe that merit of students will increase day by day. Various scholarships are being granted to students on University level. Today we can see many students are working on various research projects. Now we can see that schools of Language, Literature and Cultural Studies, Media Studies, Education Studies, etc are working in separate buildings. -

Mmtc Unpaid Dividend 30092013

FNAME MNAME LNAME FHFNAME FHMNAME FHLNAME ADD COUNTRY STATE DISTRICT PIN FOLIO INVST AMOUNT DATE PARVEZ ANSARI NA NA Indra Nagar Bhel Jhansi U P INDIA Uttar Pradesh Jhansi 1201320000 Amount for Unclaimed 4.00 30-Oct-2016 282523 and Unpaid Dividend ZACHARIAH THOMAS NA NA Po Box 47257 Fahaheel KUWAIT NA 9NRI9999 1304140005 Amount for Unclaimed 12.00 30-Oct-2016 Fahaheel Kuwait 656021 and Unpaid Dividend ANKUR VILAS KULKARNI NA NA 25, River Dr South, Aptmt # UNITED NA 9NRI9999 1203440000 Amount for Unclaimed 16.00 30-Oct-2016 2511, Jersey City, Jersey Nj STATES OF 062447 and Unpaid Dividend Usa AMERICA ERAM HASHMI NA NA House No-3031 Kaziwara INDIA Delhi 110002 IN30011811 Amount for Unclaimed 4.00 30-Oct-2016 Darya Ganj New Delhi 249819 and Unpaid Dividend DURGA DEVI NA NA 451- Robin Cinema, Subzi INDIA Delhi 110007 1201911000 Amount for Unclaimed 4.00 30-Oct-2016 Mandi Delhi Delhi 017111 and Unpaid Dividend SOM DUTT DUEVEDI NA NA D-5/5, Ii Nd Floor Rana INDIA Delhi 110007 1203450000 Amount for Unclaimed 4.00 30-Oct-2016 Pratap Bagh New Delhi 443528 and Unpaid Dividend Delhi SUNIL GOYAL NA NA D 27 Cc Colony Opp Rana INDIA Delhi 110007 IN30114310 Amount for Unclaimed 4.00 30-Oct-2016 Pratap Bagh New Delhi 427000 and Unpaid Dividend AVM ENTERPRISES PVTLTD NA NA F 40, Okhla Ind Area Phase I INDIA Delhi 110020 IN30105510 Amount for Unclaimed 8.00 30-Oct-2016 New Delhi 266034 and Unpaid Dividend 30-Oct-2016 SUDARSHA H-80 Shivaji Park Punjabi IN30011811 Amount for Unclaimed GURPREET SINGH MEHTA N SINGH MEHTA Bagh New Delhi INDIA Delhi 110026 065484 -

Maharashtra State Boatd of Sec & H.Sec Education Pune

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE PAGE : 1 College wise performance ofFresh Regular candidates for HSC 2021 Candidates passed College No. Name of the collegeStream Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 01.01.001 Z.P.BOYS JUNIOR COLLEGE, AKOLA SCIENCE 66 66 66 0 0 0 66 100.00 27050803901 ARTS 14 14 7 7 0 0 14 100.00 COMMERCE 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 100.00 TOTAL 81 81 74 7 0 0 81 100.00 01.01.002 GOVERNMENT TECHNICAL COLLEGE, AKOLA SCIENCE 17 17 16 1 0 0 17 100.00 27050117183 TOTAL 17 17 16 1 0 0 17 100.00 01.01.003 R.L.T. SCIENCE COLLEGE, AKOLA CIVIL LINE SCIENCE 544 544 543 1 0 0 544 100.00 27050117184 TOTAL 544 544 543 1 0 0 544 100.00 01.01.004 SHRI.SHIVAJI ARTS COMMERCE & SCIENCE SCIENCE 238 238 238 0 0 0 238 100.00 27050117186 COLLEGE,AKOLA ARTS 160 160 60 100 0 0 160 100.00 COMMERCE 183 183 110 73 0 0 183 100.00 TOTAL 581 581 408 173 0 0 581 100.00 01.01.005 SMT L.R.T. COMMERCE COLLEGE , AKOLA COMMERCE 761 761 748 12 1 0 761 100.00 27050117187 TOTAL 761 761 748 12 1 0 761 100.00 01.01.006 SITABAI ARTS COLLEGE, AKOLA CIVIL LINE ROAD SCIENCE 7 7 7 0 0 0 7 100.00 27050119003 ARTS 111 111 47 61 3 0 111 100.00 COMMERCE 105 105 97 8 0 0 105 100.00 MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE PAGE : 2 College wise performance ofFresh Regular candidates for HSC 2021 Candidates passed College No. -

Traders Kings and Pilgrims Page 1 of 64

CBSE-STD VI-Social Science-Traders Kings and Pilgrims Page 1 of 64 Master Lesson Plan For Traders Kings and Pilgrims Board Standard Subject Chapter Language Reference Link Creation date Traders Kings and Traders, Kings and CBSE STD VI Social Science English 2021-04-20 22:09:51 Pilgrims Pilgrims DISCLAIMER 1.Strictly not for Commercial use. 2.Provided on as is basis with no warranties of any kind. 3.Content that falls in Public Domain or common Knowledge facts can be used freely. 4.Some of the contents are owned by the Third parties and are used in compliance with their licensing conditions. Any one infringing the Copyright of such Third parties will be doing so at their own risks and costs. 5.Content can be downloaded and used for Personal, educational and informational purposes only. Any attempt to remove, alter, circumvent or distort the data that is accessed Is Illegal and strictly prohibited. ©SriSathyaSaiVidyaVahini www.srisathyasaividyavahini.org CBSE-STD VI-Social Science-Traders Kings and Pilgrims Page 2 of 64 ©SriSathyaSaiVidyaVahini www.srisathyasaividyavahini.org CBSE-STD VI-Social Science-Traders Kings and Pilgrims Page 3 of 64 Traders Kings and Pilgrims 1. MS_Objectives - Traders, Kings and Pilgrims Objectives - Traders, Kings and Pilgrims Notes to teacher: This asset lays down the proposed plan for transacting this chapter, It states the asset objectives of the MLP, This asset is for teacher’s reference and need not be taught to the students. Students will be able to - analyse the importance of trade among the major empires in the past, - trace the Silk Route and discuss its origin and importance in the spread of Buddhism, - describe the pilgrimages of famous Chinese Buddhist pilgrims, - explain the meaning and significance of Bhakti in people’s life, - compare the past trading process with the present-day technology-based trade. -

THE Tl1ird ENGLISH EMBASSY to POON~

THE Tl1IRD ENGLISH EMBASSY TO POON~ COMPRISING MOSTYN'S DIARY September, 1772-February, 1774 AND MOSTYN'S LETTERS February-177 4-Novembec- ~~:;, EDITED BY ]. H. GENSE, S. ]., PIL D. D. R. BANAJI, M. A., LL. B. BOMBAY: D. B. TARAPOREV ALA SONS & CO. " Treasure House of Books" HORNBY ROAD, FORT· COPYRIGHT l934'. 9 3 2 5.9 .. I I r\ l . 111 f, ,.! I ~rj . L.1, I \! ., ~ • I • ,. "' ' t.,. \' ~ • • ,_' Printed by 1L N. Kulkarni at the Katnatak Printing Pr6SS, "Karnatak House," Chira Bazar, Bombay 2, and Published by Jal H. D. Taraporevala, for D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Hornby Road, Fort, Bombay. PREFACE It is well known that for a hundred and fifty years after the foundation of the East India Company their representatives in ·India merely confined their activities to trade, and did not con· cern themselves with the game of building an empire in the East. But after the middle of the 18th century, a severe war broke out in Europe between England and France, now known as the Seven Years' War (1756-1763), which soon affected all the colonies and trading centres which the two nations already possessed in various parts of the globe. In the end Britain came out victorious, having scored brilliant successes both in India and America. The British triumph in India was chiefly due to Clive's masterly strategy on the historic battlefields in the Presidencies of Madras and Bengal. It should be remembered in this connection that there was then not one common or supreme authority or control over the three British establishments or Presidencies of Bengal, Madras and Bombay. -

Chapter 10—Mediaeval Administration and Social

CHRONOLOGY 1296 Ala-ud-din invades the kingdom of Devagiri, in the Deccan (p. 1). 1303 Failure of an expedition to Warangal (p. 2). 1306-1307 Expedition of Kafur (Malik Naib) to Devagiri (p. 3). 1310 Expedition to Warangal. Prataparudraveda II submits and pays tribute (p. 3). 1311 Expedition, under Malik Naib, into the Peninsula. Capture of Dvaravatipura and Madura. Mosque built at Rames-waram. Submission of the Pandya and Kerala kingdoms (pp. 4 and 5). 1311 Death of Ramchandra and accession of Shankardev (p. 6). 1316 Death of ' Ala-ud-din and accession of Shihab-ud-din ' Umar. Death of Malik Naib, Deposition of Umar and accession of Qutb-ud-din Mubarak (p. 7). 1318 Mubarak's expedition to Devagiri. Capture and death of Harpal (p. 7). 1321 Expedition to Warangal under Muhammad Jauna (Ulugh Khan) (pp. 8, 9). 1323 Second expedition to Warangal under Muhammad. Capture of Prataparudradeva II. (p. 9). 1327 Rebellion of Gurshasp (p. II). 1327 Capital transferred from Delhi to Daulatabad (p. 11). 1337 Rebellion of Nusrat Khan at Bidar (pp. 11, 12). 1340 Rebellion of Ali Shah Natthu in the Deccan (p. 12). 1346 Rebellion of the Centurions in Gujarat. Muhammad leaves Delhi for Gujarat, and suppresses the rebellion (p. 12). 1346 Rebellion in Daulatabad: Ismail Mukh proclaimed king of the Deccan. Muhammad besieges Daulatabad (p. 13). 1347 Ala-ud-din Bahman Shah proclaimed king of the Deccan. (p. 13). 1353 Rebellion of Muhammad Alam, Ali Lachin and Fakhruddin Muhurdar at Sagar (p. 15). 1358 Death of Bahman Shah and accession of Muhammad I Bahamani in the Deccan. -

GIPE-248676-Contents.Pdf (2.661Mb)

APPENDIX (I) A. SHORT NOTE ON THE PHOTOGRAPHS INSERTED IN THE Boox. No. 1. Shivaji's Seals and Coins: is a plain design including two seals, one gold coin and seven copper pieces ascribed to Shivaji., No.1 Is the principal seal used long before his corona• cion, from his very childhood and continued even after that Kignificant ceremony. The inscription, thus, is devoid of any royal insignia. Dignified in its plain majesty, the couplet, freely' rendered, reads-'This seal of Shiva, the son of Shiha. waxing ( daily ) like the crescent of the moon and adored by the universe, 11hines with benevolent splendour'. No.2 Is the closing seal and reads 'here', the limit.' No.3 Represents the obverse and reverse of a gold 'Mohur' of Shiv~ji, and bears the usual legend 'Shri RajJ. Shiva' on one aide and 'Chhatrapati' on the other. N 01. ' to 8 are the usual copper pieces called 'Shivarli.' with similar legends imprinted. No.5 bears the whole legend in full. Others carry it only partially, Nos • .& and 8 showing op.ly one letter e&ch. No. ' including nothing of regal significance ie considered to h&ve been struck before the Coronation. Nos. 9 & 10 &;e tokens of lighter weight and were known w a Ruka and Dam respectively. No. :a A Page from the Factory Record.-Thi• is inserted to ,i.,e ihe readers some idea of the nature of the or1ine.l mit.teri&l r 353 Appendix from which the extracts are made. Caref'qlly studied, the photo. graph affords a considerable knowledge of the spelling, caligraphy and similar other things in which a student ls interested.