MMP After Twenty Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iranshah Udvada Utsav

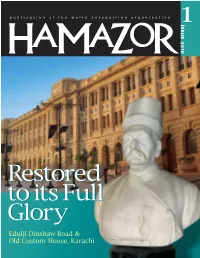

HAMAZOR - ISSUE 1 2016 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Physicist Extraordinaire, p 43 C o n t e n t s 04 WZO Calendar of Events 05 Iranshah Udvada Utsav - vahishta bharucha 09 A Statement from Udvada Samast Anjuman 12 Rules governing use of the Prayer Hall - dinshaw tamboly 13 Various methods of Disposing the Dead 20 December 25 & the Birth of Mitra, Part 2 - k e eduljee 22 December 25 & the Birth of Jesus, Part 3 23 Its been a Blast! - sanaya master 26 A Perspective of the 6th WZYC - zarrah birdie 27 Return to Roots Programme - anushae parrakh 28 Princeton’s Great Persian Book of Kings - mahrukh cama 32 Firdowsi’s Sikandar - naheed malbari 34 Becoming my Mother’s Priest, an online documentary - sujata berry COVER 35 Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE - cyrus cowasjee Image of the Imperial 39 Eduljee Dinshaw Road Project Trust - mohammed rajpar Custom House & bust of Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE. & jameel yusuf which stands at Lady 43 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Dufferin Hospital. 44 Dr Marlene Kanga, AM - interview, kersi meher-homji PHOTOGRAPHS 48 Chatting with Ami Shroff - beyniaz edulji 50 Capturing Histories - review, freny manecksha Courtesy of individuals whose articles appear in 52 An Uncensored Life - review, zehra bharucha the magazine or as 55 A Whirlwind Book Tour - farida master mentioned 57 Dolly Dastoor & Dinshaw Tamboly - recipients of recognition WZO WEBSITE 58 Delhi Parsis at the turn of the 19C - shernaz italia 62 The Everlasting Flame International Programme www.w-z-o.org 1 Sponsored by World Zoroastrian Trust Funds M e m b e r s o f t h e M a n a g i -

From Privy Council to Supreme Court: a Rite of Passage for New Zealand’S Legal System

THE HARKNESS HENRY LECTURE FROM PRIVY COUNCIL TO SUPREME COURT: A RITE OF PASSAGE FOR NEW ZEALAND’S LEGAL SYSTEM BY PROFESSOR MARGARET WILSON* I. INTRODUCTION May I first thank Harkness Henry for the invitation to deliver the 2010 Lecture. It gives me an opportunity to pay a special tribute to the firm for their support for the Waikato Law Faculty that has endured over the 20 years life of the Faculty. The relationship between academia and the profession is a special and important one. It is essential to the delivery of quality legal services to our community but also to the maintenance of the rule of law. Harkness Henry has also employed many of the fine Waikato law graduates who continue to practice their legal skills and provide leadership in the profession, including the Hamilton Women Lawyers Association that hosted a very enjoyable dinner in July. I have decided this evening to talk about my experience as Attorney General in the establish- ment of New Zealand’s new Supreme Court, which is now in its fifth year. In New Zealand, the Attorney General is a Member of the Cabinet and advises the Cabinet on legal matters. The Solici- tor General, who is the head of the Crown Law Office and chief legal official, is responsible for advising the Attorney General. It is in matters of what I would term legal policy that the Attorney General’s advice is normally sought although Cabinet also requires legal opinions from time to time. The other important role of the Attorney General is to advise the Governor General on the appointment of judges in all jurisdictions except the Mäori Land Court, where the appointment is made by the Minister of Mäori Affairs in consultation with the Attorney General. -

The 2008 Election: Reviewing Seat Allocations Without the Māori Electorate Seats June 2010

working paper The 2008 Election: Reviewing seat allocations without the Māori electorate seats June 2010 Sustainable Future Institute Working Paper 2010/04 Authors Wendy McGuinness and Nicola Bradshaw Prepared by The Sustainable Future Institute, as part of Project 2058 Working paper to support Report 8, Effective M āori Representation in Parliament : Working towards a National Sustainable Development Strategy Disclaimer The Sustainable Future Institute has used reasonable care in collecting and presenting the information provided in this publication. However, the Institute makes no representation or endorsement that this resource will be relevant or appropriate for its readers’ purposes and does not guarantee the accuracy of the information at any particular time for any particular purpose. The Institute is not liable for any adverse consequences, whether they be direct or indirect, arising from reliance on the content of this publication. Where this publication contains links to any website or other source, such links are provided solely for information purposes and the Institute is not liable for the content of such website or other source. Published Copyright © Sustainable Future Institute Limited, June 2010 ISBN 978-1-877473-56-2 (PDF) About the Authors Wendy McGuinness is the founder and chief executive of the Sustainable Future Institute. Originally from the King Country, Wendy completed her secondary schooling at Hamilton Girls’ High School and Edgewater College. She then went on to study at Manukau Technical Institute (gaining an NZCC), Auckland University (BCom) and Otago University (MBA), as well as completing additional environmental papers at Massey University. As a Fellow Chartered Accountant (FCA) specialising in risk management, Wendy has worked in both the public and private sectors. -

Hauraki-Waikato

Hauraki-Waikato Published by the Parliamentary Library July 2009 Table of Contents Hauraki-Waikato: Electoral Profile......................................................................................................................3 2008 Election Results (Electorate) .................................................................................................................4 2008 Election Results - Party Vote .................................................................................................................4 2005 Election Results (Electorate) .................................................................................................................5 2005 Election Results - Party Vote .................................................................................................................5 Voter Enrolment and Turnout 2005, 2008 .......................................................................................................6 Hauraki-Waikato: People ...................................................................................................................................7 Population Summary......................................................................................................................................7 Age Groups of the Māori Descent Population .................................................................................................7 Ethnic Groups of the Māori Descent Population..............................................................................................7 -

Maori Customary Use of Native Birds, Plants & Other Traditional Materials

NEW ZEALAND CONSERVATION AUTHORITY -- TE POU ATAWHAI TAIAO O AOTEAROA MAORI CUSTOMARY USE OF NATIVE BIRDS, PLANTS & OTHER TRADITIONAL MATERIALS ------------------------------------------------------------------------- INTERIM REPORT AND DISCUSSION PAPER -------------------------------------------------------------------------- Published by the NEW ZEALAND CONSERVATION AUTHORITY TE POU ATAWHAI TAIAO O AOTEAROA P O Box 10-420 WELLINGTON New Zealand 1997 ISBN 0-9583301-6-6 NEW ZEALAND CONSERVATION AUTHORITY -- TE POU ATAWHAI TAIAO O AOTEAROA MAORI CUSTOMARY USE OF NATIVE BIRDS, PLANTS & OTHER TRADITIONAL MATERIALS ------------------------------------------------------------------------- INTERIM REPORT AND DISCUSSION PAPER -------------------------------------------------------------------------- INTRODUCTION This is the full version of the New Zealand Conservation Authority’s Interim Report and Discussion Paper. A shorter summary version is also available, from: -- the NZCA, P O Box 10-420, Wellington, or -- your local office of the Department of Conservation. These two papers are the results thus far of an ongoing process of discussion and debate on the issue of Maori customary use of native plants and animals. The NZCA has addressed the issue through the activities of a Working Group, and the intensive debate arising from its first discussion paper in 1994. Other processes and developments have also focussed attention on the use and management of New Zealand’s indigenous natural heritage, including the WAI 262 claim to the Waitangi Tribunal, controversy over access to and disposal of dead stranded whales, and the recent Court decision on Maori fishing rights. Like the 1994 paper, this Interim Report and Discussion Paper is neither a policy nor a proposal for policy. It is not a statement of any fixed or final position of the NZCA on this issue. It does not claim to be the complete answer, or any absolute definition of Maori customary use. -

I Green Politics and the Reformation of Liberal Democratic

Green Politics and the Reformation of Liberal Democratic Institutions. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology in the University of Canterbury by R.M.Farquhar University of Canterbury 2006 I Contents. Abstract...........................................................................................................VI Introduction....................................................................................................VII Methodology....................................................................................................XIX Part 1. Chapter 1 Critical Theory: Conflict and change, marxism, Horkheimer, Adorno, critique of positivism, instrumental reason, technocracy and the Enlightenment...................................1 1.1 Mannheim’s rehabilitation of ideology and politics. Gramsci and social and political change, hegemony and counter-hegemony. Laclau and Mouffe and radical plural democracy. Talshir and modular ideology............................................................................11 Part 2. Chapter 2 Liberal Democracy: Dryzek’s tripartite conditions for democracy. The struggle for franchise in Britain and New Zealand. Extra-Parliamentary and Parliamentary dynamics. .....................29 2.1 Technocracy, New Zealand and technocracy, globalisation, legitimation crisis. .............................................................................................................................46 Chapter 3 Liberal Democracy-historical -

Is There a Civil Religious Tradition in New Zealand

The Insubstantial Pageant: is there a civil religious tradition in New Zealand? A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Religious Studies in the University of Canterbury by Mark Pickering ~ University of Canterbury 1985 CONTENTS b Chapter Page I (~, Abstract Preface I. Introduction l Plato p.2 Rousseau p.3 Bellah pp.3-5 American discussion on civil religion pp.S-8 New Zealand discussion on civil religion pp.S-12 Terms and scope of study pp.l2-14 II. Evidence 14 Speeches pp.lS-25 The Political Arena pp.25-32 Norman Kirk pp.32-40 Waitangi or New Zealand Day pp.40-46 Anzac Day pp.46-56 Other New Zealand State Rituals pp.56-61 Summary of Chapter II pp.6l-62 III. Discussion 63 Is there a civil religion in New Zealand? pp.64-71 Why has civil religion emerged as a concept? pp.71-73 What might be the effects of adopting the concept of civil religion? pp.73-8l Summary to Chapter III pp.82-83 IV. Conclusion 84 Acknowledgements 88 References 89 Appendix I 94 Appendix II 95 2 3 FEB 2000 ABSTRACT This thesis is concerned with the concept of 'civil religion' and whether it is applicable to some aspects of New zealand society. The origin, development and criticism of the concept is discussed, drawing on such scholars as Robert Bellah and John F. Wilson in the United States, and on recent New Zealand commentators. Using material such as Anzac Day and Waitangi Day commemorations, Governor-Generals' speeches, observance of Dominion Day and Empire Day, prayers in Parliament, the role of Norman Kirk, and other related phenomena, the thesis considers whether this 'evidence' substantiates the existence of a civil religion. -

Friend Or Ally? a Question for New Zealand

.......... , ---~ MeN AIR PAPERS NUMBER T\\ ELVE FRIEND OR ALLY? A QUESTION FOR NEW ZEALAND By EWAN JAMIESON THE INSTI FUTE FOR NATIONAL SI'R-~TEGIC STUDIES ! I :. ' 71. " " :~..? ~i ~ '" ,.Y:: ;,i:,.i:".. :..,-~.~......... ,,i-:i:~: .~,.:iI- " yT.. -.~ .. ' , " : , , ~'~." ~ ,?/ .... ',~.'.'.~ ..~'. ~. ~ ,. " ~:S~(::!?- ~,i~ '. ? ~ .5" .~.: -~:!~ ~:,:i.. :.~ ".: :~" ;: ~:~"~',~ ~" '" i .'.i::.. , i ::: .',~ :: .... ,- " . ".:' i:!i"~;~ :~;:'! .,"L': ;..~'~ ',.,~'i:..~,~'"~,~: ;":,:.;;, ','" ;.: i',: ''~ .~,,- ~.:.~i ~ . '~'">.'.. :: "" ,-'. ~:.." ;';, :.~';';-;~.,.";'."" .7 ,'~'!~':"~ '?'""" "~ ': " '.-."i.:2: i!;,'i ,~.~,~I~out ;popular: ~fo.rmatwn~ .o~~'t,he~,,:. "~.. " ,m/e..a~ tg:,the~6w.erw!~chi~no.wtetl~e.~gi..~e~ ;~i:~.::! ~ :: :~...i.. 5~', '+~ :: ..., .,. "'" .... " ",'.. : ~'. ,;. ". ~.~.~'.:~.'-? "-'< :! :.'~ : :,. '~ ', ;'~ : :~;.':':/.:- "i ; - :~:~!II::::,:IL:.~JmaiegMad}~)~:ib;:, ,?T,-. B~;'...-::', .:., ,.:~ .~ 'z • ,. :~.'..." , ,~,:, "~, v : ", :, -:.-'": ., ,5 ~..:. :~i,~' ',: ""... - )" . ,;'~'.i "/:~'-!"'-.i' z ~ ".. "', " 51"c, ' ~. ;'~.'.i:.-. ::,,;~:',... ~. " • " ' '. ' ".' ,This :iis .aipul~ ~'i~gtin~e ..fdi;:Na~i~real..Sfi'~te~ie.'Studi'~ ~It ;is, :not.i! -, - .... +~l~ase,~ad.~ p,g, ,,.- .~, . • ,,. .... .;. ...~,. ...... ,._ ,,. .~ .... ~;-, :'-. ,,~7 ~ ' .~.: .... .,~,~.:U7 ,L,: :.~: .! ~ :..!:.i.i.:~i :. : ':'::: : ',,-..-'i? -~ .i~ .;,.~.,;: ~v~i- ;. ~, ~;. ' ~ ,::~%~.:~.. : ..., .... .... -, ........ ....... 1'-.~ ~:-~...%, ;, .i-,i; .:.~,:- . eommenaati6'r~:~xpregseff:or ;ii~iplie'd.:;~ifl~in.:iat~ -:: -

Inequality and the 2014 New Zealand General Election

A BARK BUT NO BITE INEQUALITY AND THE 2014 NEW ZEALAND GENERAL ELECTION A BARK BUT NO BITE INEQUALITY AND THE 2014 NEW ZEALAND GENERAL ELECTION JACK VOWLES, HILDE COFFÉ AND JENNIFER CURTIN Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Vowles, Jack, 1950- author. Title: A bark but no bite : inequality and the 2014 New Zealand general election / Jack Vowles, Hilde Coffé, Jennifer Curtin. ISBN: 9781760461355 (paperback) 9781760461362 (ebook) Subjects: New Zealand. Parliament--Elections, 2014. Elections--New Zealand. New Zealand--Politics and government--21st century. Other Creators/Contributors: Coffé, Hilde, author. Curtin, Jennifer C, author. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2017 ANU Press Contents List of figures . vii List of tables . xiii List of acronyms . xvii Preface and acknowledgements . .. xix 1 . The 2014 New Zealand election in perspective . .. 1 2. The fall and rise of inequality in New Zealand . 25 3 . Electoral behaviour and inequality . 49 4. The social foundations of voting behaviour and party funding . 65 5. The winner! The National Party, performance and coalition politics . 95 6 . Still in Labour . 117 7 . Greening the inequality debate . 143 8 . Conservatives compared: New Zealand First, ACT and the Conservatives . -

Identifying Distinct Subgroups of Green Voters: a Latent Profile Analysis of Crux Values Relating to Green Party Support

Subgroups of Green Voters Identifying Distinct Subgroups of Green Voters: A Latent Profile Analysis of Crux Values Relating to Green Party Support Lucy J. Cowie, Lara M. Greaves, Chris G. Sibley University of Auckland, New Zealand Abstract In the present study we aim to explore this possibility by assessing whether The Green Party experienced unprecedented support in the 2011 New there are distinct subgroups of Green Zealand General Election. However, people may vote Green for very voters who differ in terms of their core different reasons. The Green voter base is thus likely to be comprised of social values and level of environmental a number of distinct subpopulations. We employ Latent Profile Analysis concern. to uncover subgroups within the Green voter base (n = 1,663) using data from the New Zealand Attitudes and Values Study at Time Four (2012). We The Green Party of Aotearoa delineate subgroups based on variation in attitudes about the environment, A brief history and context of the equality, wealth, social justice, climate change, and biculturalism. Core Green Green Party is warranted at this point. Liberals (56% of Green voters) showed strong support across all ideological/ The Green Party of Aotearoa can be value domains except wealth, while Green Dissonants (4%) valued the traced as far back as May 1972 to the environment and believed in anthropogenic climate change, but were low formation of the New Zealand Values across other domains. Ambivalent Biculturalists (20%) expressed strong Party, which won 2% of the vote in the support for biculturalism and weak support for social justice and equality. -

New Zealand: 2020 General Election

BRIEFING PAPER Number CBP 9034, 26 October 2020 New Zealand: 2020 By Nigel Walker general election Antonia Garraway Contents: 1. Background 2. 2020 General Election www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 New Zealand: 2020 general election Contents Summary 3 1. Background 4 2. 2020 General Election 5 2.1 Political parties 5 2.2 Party leaders 7 2.3 Election campaign 10 2.4 Election results 10 2.5 The 53rd Parliament 11 Cover page image copyright: Jacinda Ardern reopens the Dunedin Courthouse by Ministry of Justice of New Zealand – justice.govt.nz – Wikimedia Commons page. Licensed by Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) / image cropped. 3 Commons Library Briefing, 26 October 2020 Summary New Zealand held a General Election on Saturday 17 October 2020, with advance voting beginning two weeks earlier, on 3 October. Originally planned for 19 September, the election was postponed due to Covid-19. As well as electing Members of Parliament, New Zealand’s electorate voted on two referendums: one to decriminalise the recreational use of marijuana; the other to allow some terminally ill people to request assisted dying. The election was commonly dubbed the “Covid election”, with the coronavirus pandemic the main issue for voters throughout the campaign. Jacinda Ardern, the incumbent Prime Minister from the Labour Party, had been widely praised for her handling of the pandemic and the “hard and early” plan introduced by her Government in the early stages. She led in the polls throughout the campaign. Preliminary results from the election show Ms Ardern won a landslide victory, securing 49.1 per cent of the votes and a projected 64 seats in the new (53rd) Parliament: a rare outright parliamentary majority. -

Confidence and Supply Agreement with United Future New Zealand

Confidence and Supply Agreement with United Future New Zealand United Future agrees to provide confidence and supply for the term of this Parliament, to a National-led government The relationship between United Future and the government will be based on good faith and no surprises. Consultation arrangements The Government will consult with United Future on issues including: • The broad outline of the legislative programme • Key legislative measures • Major policy issues; and • Broad budget parameters. Consultation will occur in a timely fashion to ensure United Future views can be incorporated into final decision-making. Formal consultation will be managed between the Prime Minister's Office and the Office of the Leader of United Future. Other co-operation will include: • Access to relevant Ministers • Regular meetings between the Prime Minister and the United Future Leader • Advance notification to the other party of significant announcements by either the Government or United Future; and • Briefings by the Government on significant issues before any public announcement. Ministerial Position The Leader of United Future will be appointed to the positions of Minister of Revenue, Associate Minister of Health and Associate Minister of Conservation. These ministerial positions will be outside of Cabinet. 1 Policy Programme The National-led government has agreed during this term of Parliament to adopt and implement the following broad principles, policies and priorities advanced by United Future: • Passage of the Game Animal Council legislation