Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brahms and the Changing Piano

The Aesthetics of Textural Ambiguity: Brahms and the Changing Piano Augustus Arnone The thought beneath so slight a film Is more distinctly seen As laces just reveal the surge Or Mists the Apennine -Emily Dickinson Introduction In recent years, a number of performance practice scholars writing on Brahms's piano music have commented on the prominence of low-lying melodic lines, thickly-written accompaniments, and often dense saturation of the lower register.! For such writers these textural features constitute proof that Brahms could not have intended performance on the modern piano. Firms such as Steinway, Bechstein, and Chickering were manufacturing pianos by the early 1860s, roughly the midpoint of Brahms's life, that already exhibited most of the important design innovations that distinguish modern pianos from earlier ones, and these firms enjoyed enormous success across Europe.2 Performance practice scholars have argued that the increased power and sustain of these pianos create irreparable problems of balance and clarity in much of Brahms's music, implying that he was writing for the lighter and more transparent instruments that predate the modern piano, many of which were still manufactured up until the end of the century. The view that low-lying melodies and densely packed textures in the lower register present an undesirable muddiness on the modern piano was already being elaborated towards the end of the nineteenth century. During the last decades of Brahms's life, several treatises appeared elucidating the fundamental principles of what they proclaimed to be the "modern school of pianoforte playing." Three treatises in particular, those by Hans Schmitt (1893), Aleksandr Nikitich Bukhovtsev (1897), and Adolph Christiani (c. -

Brahms Symphony 2 Gardiner

Brahms Symphony 2 Gardiner 1 Johannes Brahms 1833-1897 1 Alto Rhapsody Op.53 (1869) 12:57 Franz Schubert 1797-1828 2 Gesang der Geister über den Wassern D714 (1821) 12:18 3 Gruppe aus dem Tartarus D583 (1817, arr. Brahms 1871) 2:20 4 An Schwager Kronos D369 (1816, arr. Brahms 1871) 2:28 Symphony No.2 in D major Op.73 (1877) 5 I Allegro non troppo 19:42 6 II Adagio non troppo – L’istesso tempo, ma grazioso 9:28 7 III Allegretto grazioso (quasi andantino) – Presto ma non assai – Tempo I 5:06 8 IV Allegro con spirito 9:05 73:59 Nathalie Stutzmann contralto Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique The Monteverdi Choir John Eliot Gardiner Recorded live at the Salle Pleyel, Paris, November 2007 2 Brahms: Roots and memory John Eliot Gardiner To me Brahms’ large-scale music is brimful of vigour, drama and a driving passion. ‘Fuego y cristal’ was how Jorge Luis Borges once described it. How best to release all that fire and crystal, then? One way is to set his symphonies in the context of his own superb and often neglected choral music, and that of the old masters he particularly cherished (Schütz and Bach especially) and of recent heroes of his (Mendelssohn, Schubert and Schumann). This way we are able to gain a new perspective on his symphonic compositions, drawing attention to the intrinsic vocality at the heart of his writing for orchestra. Composing such substantial choral works as the Schicksalslied, the Alto Rhapsody, Nänie and the German Requiem gave Brahms invaluable experience of orchestral writing years before he brought his first symphony to fruition: they were the vessels for some of his most profound thoughts, revealing at times an almost desperate urge to communicate things of import. -

Crane Chorus Crane Symphony Orchestra

JOHANNES BRAHMS A German Requiem JOSEPH FLUMMERFELT, Conductor 2015 Dorothy Albrecht Gregory Visiting Conductor* with the Crane Chorus and the Crane Symphony Orchestra NICOLE CABELL, soprano CRAIG VERM, baritone Saturday, May 2, 2015 at 7:30 pm Hosmer Hall at SUNY Potsdam *The partnership of the Dorothy Albrecht The Lougheed-Kofoed Festival of the Gregory Visiting Conductor Fund, established Arts is made possible by the generosity by Dorothy Albrecht Gregory ’61, and the and artistic vision of Kathryn (Kofoed) Adeline Maltzan Crane Chorus Performance ’54 and Donald Lougheed (Hon. ’54). Tour Fund, established by Dr. Gary C. Jaquay ’67, brings distinguished conductors to The Crane Media Sponsor School of Music for festival performances by the Crane Chorus and Crane Symphony Orchestra, and funds travel for major performances to venues outside of Potsdam. Welcome to the concluding performance of the fourth Lougheed-Kofoed Festival of the Arts, whose scope embracing all the arts, in a continuation of our campus’ historic Spring Festival of the Arts, is generously supported by the visionary gifts of Kathy Kofoed Lougheed ’54 and her husband Don Lougheed (Hon.) ’54. The featured choral-orchestral work on this evening’s program, Johannes Brahms’ beloved German Requiem, had been among those performed most frequently in the Spring Festival, having been featured on nine separate occasions, and having been conducted by some of the iconic figures in the Festival’s history. Helen Hosmer herself conducted it just two years after the beginning of this venerable series, in 1934; and in 1939 her friend and colleague Nadia Boulanger conducted the work. -

Brahms, Johannes (B Hamburg, 7 May 1833; D Vienna, 3 April 1897)

Brahms, Johannes (b Hamburg, 7 May 1833; d Vienna, 3 April 1897). German composer. The successor to Beethoven and Schubert in the larger forms of chamber and orchestral music, to Schubert and Schumann in the miniature forms of piano pieces and songs, and to the Renaissance and Baroque polyphonists in choral music, Brahms creatively synthesized the practices of three centuries with folk and dance idioms and with the language of mid and late 19thcentury art music. His works of controlled passion, deemed reactionary and epigonal by some, progressive by others, became well accepted in his lifetime. 1. Formative years. 2. New paths. 3. First maturity. 4. At the summit. 5. Final years and legacy. 6. Influence and reception. 7. Piano and organ music. 8. Chamber music. 9. Orchestral works and concertos. 10. Choral works. 11. Lieder and solo vocal ensembles. WORKS BIBLIOGRAPHY GEORGE S. BOZARTH (1–5, 10–11, worklist, bibliography), WALTER FRISCH (6– 9, 10, worklist, bibliography) Brahms, Johannes 1. Formative years. Brahms was the second child and first son of Johanna Henrika Christiane Nissen (1789–1865) and Johann Jakob Brahms (1806–72). His mother, an intelligent and thrifty woman simply educated, was a skilled seamstress descended from a respectable bourgeois family. His father came from yeoman and artisan stock that originated in lower Saxony and resided in Holstein from the mid18th century. A resourceful musician of modest talent, Johann Jakob learnt to play several instruments, including the flute, horn, violin and double bass, and in 1826 moved to the free Hanseatic port of Hamburg, where he earned his living playing in dance halls and taverns. -

3982.Pdf (118.1Kb)

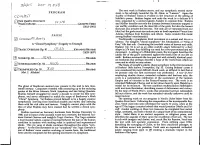

II 3/k·YC)) b,~ 1'1 ,~.>u The next work in Brahms oeuvre, and our symphonic second move . PROGRAM ment, is his achingly beautiful Op. 82, Niinie, or "Lament." Again the Ci) I~ /6':; / duality of Brahms vision is evident in the structure of the setting of Schiller's poem. Brahms begins and ends the work in a delicate 6/4 v time, separated by a central majestic Andante in common time. Brahms lD~B~=':~i.~.~~ f~.:..::.?.................... GIU~3-':;') and Schiller describe not only the distance between humanity trapped in ............. our earthly condition and the ideal life of the gods, but also the lament "" that pain also invades the heavens. Not only are we separated from our bliss, but the gods must also endure pain as death separated Venus from Adonis, Orpheus from Euridice, and others. Some consider this music PAUSE among Brahms' most beautiful. r;J ~ ~\.e;Vll> I Boe (5 Traditionally a symphonic third movement is a minuet and trio or a scherzo. For tonight's "choral symphony" the Schicksalslied, or "Song of A "Choral Symphony" -Tragedy to Triumph Fate," fills that role. Continuing the two-fold vision of heaven and earth, Brahms' Op. 54 is set as an other-worldly adagio followed by a fiery ~ TRAGIC OVERTURE Op. 81 .......... L~:.s..:>.................JOHANNES BRAHMS allegro in 3/4 time, thus fulfilling our need for a two-part minuet and trio (1833-1897) movement. A setting of a HOideriein poem, the text again describes the idyllic life of the god's contrasted against the fearful fate of our life on NANIE Op. -

The First Piano Concerto of Johannes Brahms: Its History and Performance Practice

THE FIRST PIANO CONCERTO OF JOHANNES BRAHMS: ITS HISTORY AND PERFORMANCE PRACTICE A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS by Mark Livshits Diploma Date August 2017 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Joyce Lindorff, Advisory Chair, Keyboard Studies Dr. Charles Abramovic, Keyboard Studies Dr. Michael Klein, Music Studies Dr. Maurice Wright, External Member, Temple University, Music Studies ABSTRACT In recent years, Brahms’s music has begun to occupy a larger role in the consciousness of musicologists, and with this surge of interest came a refreshingly original approach to his music. Although the First Piano Concerto op. 15 of Johannes Brahms is a beloved part of the standard piano repertoire, there is a curious under- representation of the work through the lens of historical performance practice. This monograph addresses the various aspects that comprise a thorough performance practice analysis of the concerto. These include pedaling, articulation, phrasing, and questions of tempo, an element that takes on greater importance beyond just complicating matters technically. These elements are then put into the context of Brahms’s own pianism, conducting, teaching, and musicological endeavors based on first and second-hand accounts of the composer’s work. It is the combining of these concepts that serves to illuminate the concerto in a far more detailed fashion, and ultimately enabling us to re-evaluate whether the time honored modern interpretations of the work fall within the boundaries that Brahms himself would have considered effective and accurate. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to my committee and Dr. -

Shepherd School Chamber Orchestra

RICE CHORALE THOMAS JABER , music director SHEPHERD SCHOOL CHAMBER ORCHESTRA LARRY RACHLEFF, music director THOMAS JABER, conductor Thursday, October 27, 1994 8:00p.m. Stude Concert Hall c~ RICE UNNERSITY SchOol Of Music PROGRAM Schicksalslied (Song of Destiny), Op. 54 Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) You wander on high in light on ground that is soft, blessed spirits! Shining, godly zephyrs brush you as lightly as the player's fingers brush holy strings. Fateless, like sleeping infants, the Celestial breathe. They are chastely preserved in modest bud. In eternal blossom their spirit lives and their blissful eyes gaze in calm clarity. Yet to us is given no place to rest. They vanish, they fall, suffering mortals, blindly from one hour to the next, ,... • J like water flung from cliff to clifffor years down into the unknown. [Friedrich Holder/in] INTERMISSION Requiem, K. 626 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) .. edited by Richard Maunder I. Requiem aeternam Eternal rest grant them, 0 Lord; and may perpetual light shine upon them. A hymn, 0 God, becometh Thee in Sion, and a vow shall be paid to Thee in Jerusalem. Hear my prayer; to Thee all flesh shall come. Eternal rest, etc. Michelle Jockers, soprano II. Kyrie Lord, have mercy, Christ, have mercy, Lord, have mercy. III. Dies irae Day of wrath, that day shall dissolve the world into embers, as David prophesied with the Sibyl. How great the trembling will be, when the Judge shall come, the rigorous investigator of all things I IV. Tuba mirum The trumpet, spreading its wondrous sound through the tombs of every land, will summon all before the throne. -

Unknown Brahms.’ We Hear None of His Celebrated Overtures, Concertos Or Symphonies

PROGRAM NOTES November 19 and 20, 2016 This weekend’s program might well be called ‘Unknown Brahms.’ We hear none of his celebrated overtures, concertos or symphonies. With the exception of the opening work, all the pieces are rarities on concert programs. Spanning Brahms’s youth through his early maturity, the music the Wichita Symphony performs this weekend broadens our knowledge and appreciation of this German Romantic genius. Hungarian Dance No. 6 Johannes Brahms Born in Hamburg, Germany May 7, 1833 in Hamburg, Germany Died April 3, 1897 in Vienna, Austria Last performed March 28/29, 1992 We don’t think of Brahms as a composer of pure entertainment music. He had as much gravitas as any 19th-century master and is widely regarded as a great champion of absolute music, music in its purest, most abstract form. Yet Brahms loved to quaff a stein or two of beer with friends and, within his circle, was treasured for his droll sense of humor. His Hungarian Dances are perhaps the finest examples of this side of his character: music for relaxation and diversion, intended to give pleasure to both performer and listener. Their music is familiar and beloved - better known to the general public than many of Brahms’s concert works. Thus it comes as a surprise to many listeners to learn that Brahms specifically denied authorship of their melodies. He looked upon these dances as arrangements, yet his own personality is so evident in them that they beg for consideration as original compositions. But if we deem them to be authentic Brahms, do we categorize them as music for one-piano four-hands, solo piano, or orchestra? Versions for all three exist in Brahms's hand. -

Kansas State University Orchestra Programs 1990—2018 Updated January 13, 2018 David Littrell, Conductor

Kansas State University Orchestra Programs 1990—2018 updated January 13, 2018 David Littrell, conductor 1990-1991 October 16, 1990 Tragic Overture, Op. 81 Brahms Oboe Concerto R. Strauss Dr. Sara Funkhouser, oboe Symphony No. 4 in C Minor (“Tragic”) Schubert December 11, 1990 Orchestral Suite No. 1 in C Major, BWV 1066 JS Bach “Vedrai, carino” from Don Giovanni Mozart Dayna Snook, mezzo-soprano Scaramouche Suite, 2nd & 3rd mvts. Milhaud Christopher Goins, alto saxophone “Son vergin vezzosa” from I Puritani Bellini Ai-ze Wang, soprano Symphony No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 10 Shostakovich April 4-5-6, 1991 The Magic Flute (Opera) Mozart April 23, 1991 Overture to Ruy Blas Mendelssohn Symphony No. 101 in D Major (“Clock”) Haydn Symphony No. 5 in Eb Major, Op. 82 Sibelius 1991-1992 October 1, 1991 Overture to Il Signor Bruschino Rossini Concerto Grosso for Four String Orchestras Vaughan Williams assisting musicians: Manhattan public school string students Symphony No. 2 in B Minor Borodin repeat performance October 2, 1991 at Concordia KS October 24-25-26, 1991 West Side Story Bernstein December 9, 1991 In Memoriam, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Sinfonia concertante in Eb Major, K. 364 Mozart Cora Cooper, violin Melinda Scherer Bootz, viola Requiem, K. 626 Mozart John Alldis, guest conductor soloists: Lori Zoll, Juli Borst, Rob Fann, Andy Stuckey KSU Concert Choir March 3, 1992 Overture to Der Freischütz von Weber “Faites-lui mes aveux” from Faust Gounod Juli Borst, mezzo-soprano “Ah, per sempre” from I Puritani Bellini Andy Stuckey, baritone Concerto in D Haydn Lisa Leuthold, horn Symphony No. -

Historicism and German Nationalism in Max Reger's Requiems

Historicism and German Nationalism in Max Reger’s Requiems Katherine FitzGibbon Background: Historicism and German During the nineteenth century, German Requiems composers began creating alternative German Requiems that used either German literary material, as in Schumann’s Requiem für ermans have long perceived their Mignon with texts by Goethe, or German literary and musical traditions as being theology, as in selections from Luther’s of central importance to their sense of translation of the Bible in Brahms’s Ein Gnational identity. Historians and music scholars in deutsches Requiem. The musical sources tended the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to be specifically German as well; composers sought to define specifically German attributes in made use of German folk materials, German music that elevated the status of German music, spiritual materials such as the Lutheran chorale, and of particular canonic composers. and historical forms and ideas like the fugue, the pedal point, antiphony, and other devices derived from Bach’s cantatas and Schütz’s funeral music. It was the Requiem that became an ideal vehicle for transmitting these German ideals. Although there had long been a tradition of As Daniel Beller-McKenna notes, Brahms’s Ein German Lutheran funeral music, it was only in deutsches Requiem was written at the same the nineteenth century that composers began time as Germany’s move toward unification creating alternatives to the Catholic Requiem under Kaiser Wilhelm and Bismarck. While with the same monumental scope (and the same Brahms exhibited some nationalist sympathies— title). Although there were several important he owned a bust of Bismarck and wrote the examples of Latin Requiems by composers like jingoistic Triumphlied—his Requiem became Mozart, none used the German language or the Lutheran theology that were of particular importance to the Prussians. -

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Through Brahms the ninth season July 22–August 13, 2011 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 Through Brahms Program Overview 6 Essay: “Johannes Brahms: The Great Romantic” by Calum MacDonald 8 Encounters I–IV 11 Concert Programs I–VI 30 String Quartet Programs 37 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 50 Chamber Music Institute 52 Prelude Performances 61 Koret Young Performers Concerts 64 Café Conversations 65 Master Classes 66 Open House 67 2011 Visual Artist: John Morra 68 Listening Room 69 Music@Menlo LIVE 70 2011–2012 Winter Series 72 Artist and Faculty Biographies 85 Internship Program 86 Glossary 88 Join Music@Menlo 92 Acknowledgments 95 Ticket and Performance Information 96 Calendar Cover artwork: Mertz No. 12, 2009, by John Morra. Inside (p. 67): Paintings by John Morra. Photograph of Johannes Brahms in his studio (p. 1): © The Art Archive/Museum der Stadt Wien/ Alfredo Dagli Orti. Photograph of the grave of Johannes Brahms in the Zentralfriedhof (central cemetery), Vienna, Austria (p. 5): © Chris Stock/Lebrecht Music and Arts. Photograph of Brahms (p. 7): Courtesy of Eugene Drucker in memory of Ernest Drucker. Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 69) and Ani Kavafian (p. 75): Christian Steiner. Paul Appleby (p. 72): Ken Howard. Carey Bell (p. 73): Steve Savage. Sasha Cooke (p. 74): Nick Granito. -

1 CURRICULUM VITAE for MARGARET NOTLEY Business

1 CURRICULUM VITAE FOR MARGARET NOTLEY Business Contact Information: Personal Contact Information: College of Music 1904 Hollyhill Lane University of North Texas Denton, TX 76205 (940) 565–3751 (940) 390–1980 [email protected] [email protected] EDUCATION Yale University: M.Phil., PhD in music (1985–1992) Mannes College of Music: piano major (Fall 1972–Winter 1973) Barnard College of Columbia University: A.B. magna cum laude; English major (1967–71) Full-time piano studies with Edith Oppens (1972–76) and Sophia Rosoff (1976–80) EMPLOYMENT Professor of Music at University of North Texas (Fall 2011–) Associate Professor of Musicology at University of North Texas (Fall 2006–Spring 2011) Assistant Professor of Musicology at University of North Texas (Fall 2000–Spring 2006) Full-time Lecturer in Musicology at University of North Texas (1999–2000) Part-time Lecturer at University of Connecticut, Storrs (Fall 1997) Full-time Lecturer at Yale University (1992–93) Part-time Instructor at Yale University (Spring 1990) Part-time research assistant (1971–83) for The Poetical Works of Oliver Wendell Holmes, revised and with a new introduction by Eleanor M. Tilton (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1975); and volumes 7–9 of The Letters of Ralph Waldo Emerson, edited by Eleanor M. Tilton (New York, Columbia University Press, 1990, 1991, 1994). GRANTS AND FELLOWSHIPS External October 2015: Franklin Research Grant, American Philosophical Society ($6,000) Mid-May through June 2011: Franklin Research Grant, American Philosophical Society ($6,000) 2 Mid-May through mid-July 2001: Fulbright Scholar Grant, Austrian-American Educational Commission and J. William Fulbright Foreign Scholarship Board (70,000 Schillings) January-December 1996: Fellowship for College Teachers and Independent Scholars, National Endowment for the Humanities ($22,750) 1996–97: I was offered a fellowship by the American Council of Learned Societies but had to decline it because I accepted the NEH Fellowship instead.