Physics 120 Lab 8 (2019) Bipolar Junction Transistors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 7: AC Transistor Amplifiers

Chapter 7: Transistors, part 2 Chapter 7: AC Transistor Amplifiers The transistor amplifiers that we studied in the last chapter have some serious problems for use in AC signals. Their most serious shortcoming is that there is a “dead region” where small signals do not turn on the transistor. So, if your signal is smaller than 0.6 V, or if it is negative, the transistor does not conduct and the amplifier does not work. Design goals for an AC amplifier Before moving on to making a better AC amplifier, let’s define some useful terms. We define the output range to be the range of possible output voltages. We refer to the maximum and minimum output voltages as the rail voltages and the output swing is the difference between the rail voltages. The input range is the range of input voltages that produce outputs which are not at either rail voltage. Our goal in designing an AC amplifier is to get an input range and output range which is symmetric around zero and ensure that there is not a dead region. To do this we need make sure that the transistor is in conduction for all of our input range. How does this work? We do it by adding an offset voltage to the input to make sure the voltage presented to the transistor’s base with no input signal, the resting or quiescent voltage , is well above ground. In lab 6, the function generator provided the offset, in this chapter we will show how to design an amplifier which provides its own offset. -

Power Electronics

Diodes and Transistors Semiconductors • Semiconductor devices are made of alternating layers of positively doped material (P) and negatively doped material (N). • Diodes are PN or NP, BJTs are PNP or NPN, IGBTs are PNPN. Other devices are more complex Diodes • A diode is a device which allows flow in one direction but not the other. • When conducting, the diodes create a voltage drop, kind of acting like a resistor • There are three main types of power diodes – Power Diode – Fast recovery diode – Schottky Diodes Power Diodes • Max properties: 1500V, 400A, 1kHz • Forward voltage drop of 0.7 V when on Diode circuit voltage measurements: (a) Forward biased. (b) Reverse biased. Fast Recovery Diodes • Max properties: similar to regular power diodes but recover time as low as 50ns • The following is a graph of a diode’s recovery time. trr is shorter for fast recovery diodes Schottky Diodes • Max properties: 400V, 400A • Very fast recovery time • Lower voltage drop when conducting than regular diodes • Ideal for high current low voltage applications Current vs Voltage Characteristics • All diodes have two main weaknesses – Leakage current when the diode is off. This is power loss – Voltage drop when the diode is conducting. This is directly converted to heat, i.e. power loss • Other problems to watch for: – Notice the reverse current in the recovery time graph. This can be limited through certain circuits. Ways Around Maximum Properties • To overcome maximum voltage, we can use the diodes in series. Here is a voltage sharing circuit • To overcome maximum current, we can use the diodes in parallel. -

Notes for Lab 1 (Bipolar (Junction) Transistor Lab)

ECE 327: Electronic Devices and Circuits Laboratory I Notes for Lab 1 (Bipolar (Junction) Transistor Lab) 1. Introduce bipolar junction transistors • “Transistor man” (from The Art of Electronics (2nd edition) by Horowitz and Hill) – Transistors are not “switches” – Base–emitter diode current sets collector–emitter resistance – Transistors are “dynamic resistors” (i.e., “transfer resistor”) – Act like closed switch in “saturation” mode – Act like open switch in “cutoff” mode – Act like current amplifier in “active” mode • Active-mode BJT model – Collector resistance is dynamically set so that collector current is β times base current – β is assumed to be very high (β ≈ 100–200 in this laboratory) – Under most conditions, base current is negligible, so collector and emitter current are equal – β ≈ hfe ≈ hFE – Good designs only depend on β being large – The active-mode model: ∗ Assumptions: · Must have vEC > 0.2 V (otherwise, in saturation) · Must have very low input impedance compared to βRE ∗ Consequences: · iB ≈ 0 · vE = vB ± 0.7 V · iC ≈ iE – Typically, use base and emitter voltages to find emitter current. Finish analysis by setting collector current equal to emitter current. • Symbols – Arrow represents base–emitter diode (i.e., emitter always has arrow) – npn transistor: Base–emitter diode is “not pointing in” – pnp transistor: Emitter–base diode “points in proudly” – See part pin-outs for easy wiring key • “Common” configurations: hold one terminal constant, vary a second, and use the third as output – common-collector ties collector -

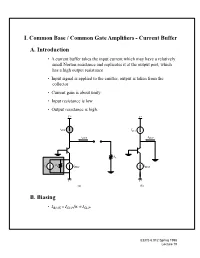

I. Common Base / Common Gate Amplifiers

I. Common Base / Common Gate Amplifiers - Current Buffer A. Introduction • A current buffer takes the input current which may have a relatively small Norton resistance and replicates it at the output port, which has a high output resistance • Input signal is applied to the emitter, output is taken from the collector • Current gain is about unity • Input resistance is low • Output resistance is high. V+ V+ i SUP ISUP iOUT IOUT RL R is S IBIAS IBIAS V− V− (a) (b) B. Biasing = /α ≈ • IBIAS ISUP ISUP EECS 6.012 Spring 1998 Lecture 19 II. Small Signal Two Port Parameters A. Common Base Current Gain Ai • Small-signal circuit; apply test current and measure the short circuit output current ib iout + = β v r gmv oib r − o ve roc it • Analysis -- see Chapter 8, pp. 507-509. • Result: –β ---------------o ≅ Ai = β – 1 1 + o • Intuition: iout = ic = (- ie- ib ) = -it - ib and ib is small EECS 6.012 Spring 1998 Lecture 19 B. Common Base Input Resistance Ri • Apply test current, with load resistor RL present at the output + v r gmv r − o roc RL + vt i − t • See pages 509-510 and note that the transconductance generator dominates which yields 1 Ri = ------ gm µ • A typical transconductance is around 4 mS, with IC = 100 A • Typical input resistance is 250 Ω -- very small, as desired for a current amplifier • Ri can be designed arbitrarily small, at the price of current (power dissipation) EECS 6.012 Spring 1998 Lecture 19 C. Common-Base Output Resistance Ro • Apply test current with source resistance of input current source in place • Note roc as is in parallel with rest of circuit g v m ro + vt it r − oc − v r RS + • Analysis is on pp. -

ECE 255, MOSFET Basic Configurations

ECE 255, MOSFET Basic Configurations 8 March 2018 In this lecture, we will go back to Section 7.3, and the basic configurations of MOSFET amplifiers will be studied similar to that of BJT. Previously, it has been shown that with the transistor DC biased at the appropriate point (Q point or operating point), linear relations can be derived between the small voltage signal and current signal. We will continue this analysis with MOSFETs, starting with the common-source amplifier. 1 Common-Source (CS) Amplifier The common-source (CS) amplifier for MOSFET is the analogue of the common- emitter amplifier for BJT. Its popularity arises from its high gain, and that by cascading a number of them, larger amplification of the signal can be achieved. 1.1 Chararacteristic Parameters of the CS Amplifier Figure 1(a) shows the small-signal model for the common-source amplifier. Here, RD is considered part of the amplifier and is the resistance that one measures between the drain and the ground. The small-signal model can be replaced by its hybrid-π model as shown in Figure 1(b). Then the current induced in the output port is i = −gmvgs as indicated by the current source. Thus vo = −gmvgsRD (1.1) By inspection, one sees that Rin = 1; vi = vsig; vgs = vi (1.2) Thus the open-circuit voltage gain is vo Avo = = −gmRD (1.3) vi Printed on March 14, 2018 at 10 : 48: W.C. Chew and S.K. Gupta. 1 One can replace a linear circuit driven by a source by its Th´evenin equivalence. -

Precision Current Sources and Sinks Using Voltage References

Application Report SNOAA46–June 2020 Precision Current Sources and Sinks Using Voltage References Marcoo Zamora ABSTRACT Current sources and sinks are common circuits for many applications such as LED drivers and sensor biasing. Popular current references like the LM134 and REF200 are designed to make this choice easier by requiring minimal external components to cover a broad range of applications. However, sometimes the requirements of the project may demand a little more than what these devices can provide or set constraints that make them inconvenient to implement. For these cases, with a voltage reference like the TL431 and a few external components, one can create a simple current bias with high performance that is flexible to fit meet the application requirements. Current sources and sinks have been covered extensively in other Texas Instruments application notes such as SBOA046 and SLYC147, but this application note will cover other common current sources that haven't been previously discussed. Contents 1 Precision Voltage References.............................................................................................. 1 2 Current Sink with Voltage References .................................................................................... 2 3 Current Source with Voltage References................................................................................. 4 4 References ................................................................................................................... 6 List of Figures 1 Current -

Lecture 12 Digital Circuits (II) MOS INVERTER CIRCUITS

Lecture 12 Digital Circuits (II) MOS INVERTER CIRCUITS Outline • NMOS inverter with resistor pull-up –The inverter • NMOS inverter with current-source pull-up • Complementary MOS (CMOS) inverter • Static analysis of CMOS inverter Reading Assignment: Howe and Sodini; Chapter 5, Section 5.4 6.012 Spring 2007 Lecture 12 1 1. NMOS inverter with resistor pull-up: Dynamics •CL pull-down limited by current through transistor – [shall study this issue in detail with CMOS] •CL pull-up limited by resistor (tPLH ≈ RCL) • Pull-up slowest VDD VDD R R VOUT: VOUT: HI LO LO HI V : VIN: IN C LO HI CL HI LO L pull-down pull-up 6.012 Spring 2007 Lecture 12 2 1. NMOS inverter with resistor pull-up: Inverter design issues Noise margins ↑⇒|Av| ↑⇒ •R ↑⇒|RCL| ↑⇒ slow switching •gm ↑⇒|W| ↑⇒ big transistor – (slow switching at input) Trade-off between speed and noise margin. During pull-up we need: • High current for fast switching • But also high incremental resistance for high noise margin. ⇒ use current source as pull-up 6.012 Spring 2007 Lecture 12 3 2. NMOS inverter with current-source pull-up I—V characteristics of current source: iSUP + 1 ISUP r i oc vSUP SUP _ vSUP Equivalent circuit models : iSUP + ISUP r r vSUP oc oc _ large-signal model small-signal model • High current throughout voltage range vSUP > 0 •iSUP = 0 for vSUP ≤ 0 •iSUP = ISUP + vSUP/ roc for vSUP > 0 • High small-signal resistance roc. 6.012 Spring 2007 Lecture 12 4 NMOS inverter with current-source pull-up Static Characteristics VDD iSUP VOUT VIN CL Inverter characteristics : iD = V 4 3 VIN VGS I + DD SUP roc 2 1 = vOUT vDS VDD (a) VOUT 1 2 3 4 VIN (b) High roc ⇒ high noise margins 6.012 Spring 2007 Lecture 12 5 PMOS as current-source pull-up I—V characteristics of PMOS: + S + VSG _ VSD G B − _ + IDp 5 V + D − V + G − V − D − ID(VSG,VSD) (a) = VSG 3.5 V 300 V = V + V = V − 1 V 250 (triode SD SG Tp SG region) V = 3 V 200 SG − IDp (µA) (saturation region) 150 = VSG 25 100 = 0, 0.5, VSG 1 V (cutoff region) V = 2 V 50 SG = VSG 1.5 V 12345 VSD (V) (b) Note: enhancement-mode PMOS has VTp <0. -

6 Insulated-Gate Field-Effect Transistors

Chapter 6 INSULATED-GATE FIELD-EFFECT TRANSISTORS Contents 6.1 Introduction ......................................301 6.2 Depletion-type IGFETs ...............................302 6.3 Enhancement-type IGFETs – PENDING .....................311 6.4 Active-mode operation – PENDING .......................311 6.5 The common-source amplifier – PENDING ...................312 6.6 The common-drain amplifier – PENDING ....................312 6.7 The common-gate amplifier – PENDING ....................312 6.8 Biasing techniques – PENDING ..........................312 6.9 Transistor ratings and packages – PENDING .................312 6.10 IGFET quirks – PENDING .............................313 6.11 MESFETs – PENDING ................................313 6.12 IGBTs ..........................................313 *** INCOMPLETE *** 6.1 Introduction As was stated in the last chapter, there is more than one type of field-effect transistor. The junction field-effect transistor, or JFET, uses voltage applied across a reverse-biased PN junc- tion to control the width of that junction’s depletion region, which then controls the conduc- tivity of a semiconductor channel through which the controlled current moves. Another type of field-effect device – the insulated gate field-effect transistor, or IGFET – exploits a similar principle of a depletion region controlling conductivity through a semiconductor channel, but it differs primarily from the JFET in that there is no direct connection between the gate lead 301 302 CHAPTER 6. INSULATED-GATE FIELD-EFFECT TRANSISTORS and the semiconductor material itself. Rather, the gate lead is insulated from the transistor body by a thin barrier, hence the term insulated gate. This insulating barrier acts like the di- electric layer of a capacitor, and allows gate-to-source voltage to influence the depletion region electrostatically rather than by direct connection. In addition to a choice of N-channel versus P-channel design, IGFETs come in two major types: enhancement and depletion. -

Chapter 10 Differential Amplifiers

Chapter 10 Differential Amplifiers 10.1 General Considerations 10.2 Bipolar Differential Pair 10.3 MOS Differential Pair 10.4 Cascode Differential Amplifiers 10.5 Common-Mode Rejection 10.6 Differential Pair with Active Load 1 Audio Amplifier Example An audio amplifier is constructed as above that takes a rectified AC voltage as its supply and amplifies an audio signal from a microphone. CH 10 Differential Amplifiers 2 “Humming” Noise in Audio Amplifier Example However, VCC contains a ripple from rectification that leaks to the output and is perceived as a “humming” noise by the user. CH 10 Differential Amplifiers 3 Supply Ripple Rejection vX Avvin vr vY vr vX vY Avvin Since both node X and Y contain the same ripple, their difference will be free of ripple. CH 10 Differential Amplifiers 4 Ripple-Free Differential Output Since the signal is taken as a difference between two nodes, an amplifier that senses differential signals is needed. CH 10 Differential Amplifiers 5 Common Inputs to Differential Amplifier vX Avvin vr vY Avvin vr vX vY 0 Signals cannot be applied in phase to the inputs of a differential amplifier, since the outputs will also be in phase, producing zero differential output. CH 10 Differential Amplifiers 6 Differential Inputs to Differential Amplifier vX Avvin vr vY Avvin vr vX vY 2Avvin When the inputs are applied differentially, the outputs are 180° out of phase; enhancing each other when sensed differentially. CH 10 Differential Amplifiers 7 Differential Signals A pair of differential signals can be generated, among other ways, by a transformer. -

Transistor Current Source

PY 452 Advanced Physics Laboratory Hans Hallen Electronics Labs One electronics project should be completed. If you do not know what an op-amp is, do either lab 2 or lab 3. A written report is due, and should include a discussion of the circuit with inserted equations and plots as appropriate to substantiate the words and show that the measurements were taken. The report should not consist of the numbered items below and short answers, but should be one coherent discussion that addresses most of the issues brought out in the numbered items below. This is not an electronics course. Familiarity with electronics concepts such as input and output impedance, noise sources and where they matter, etc. are important in the lab AND SHOULD APPEAR IN THE REPORT. The objective of this exercise is to gain familiarity with these concepts. Electronics Lab #1 Transistor Current Source Task: Build and test a transistor current source, , +V with your choice of current (but don't exceed the transistor, power supply, or R ratings). R1 Rload You may wish to try more than one current. (1) Explain your choice of R1, R2, and Rsense. VCE (a) In particular, use the 0.6 V drop of VBE - rule for current flow to calculate I in R2 VBE Rsense terms of Rsense, and the Ic/Ib rule to estimate Ib hence the values of R1&R2. (2) Try your source over a wide range of Rload values, plot Iload vs. Rload and interpret. You may find it instructive to look at VBE and VCE with a floating (neither side grounded) multimeter. -

High-Impedance Fault Diagnosis: a Review

energies Review High-Impedance Fault Diagnosis: A Review Abdulaziz Aljohani 1,* and Ibrahim Habiballah 2 1 Unconventional Resources Engineering and Project Management Department, Saudi Arabian Oil Company (Saudi Aramco), Dhahran 31311, Saudi Arabia 2 Electrical Engineering Department, King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, Dhahran 31261, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 9 November 2020; Accepted: 30 November 2020; Published: 5 December 2020 Abstract: High-impedance faults (HIFs) represent one of the biggest challenges in power distribution networks. An HIF occurs when an electrical conductor unintentionally comes into contact with a highly resistive medium, resulting in a fault current lower than 75 amperes in medium-voltage circuits. Under such condition, the fault current is relatively close in value to the normal drawn ampere from the load, resulting in a condition of blindness towards HIFs by conventional overcurrent relays. This paper intends to review the literature related to the HIF phenomenon including models and characteristics. In this work, detection, classification, and location methodologies are reviewed. In addition, diagnosis techniques are categorized, evaluated, and compared with one another. Finally, disadvantages of current approaches and a look ahead to the future of fault diagnosis are discussed. Keywords: high-impedance fault; fault detection techniques; fault location techniques; modeling; machine learning; signal processing; artificial neural networks; wavelet transform; Stockwell transform 1. Introduction High-impedance faults (HIFs) represent a persistent issue in the field of power system protection. Hence, a comprehensive understanding of such faults is a necessity for many engineers in order to innovate practical solutions. The authors of [1,2] introduced an HIF detection-oriented review. -

Differential Amplifiers

www.getmyuni.com Operational Amplifiers: The operational amplifier is a direct-coupled high gain amplifier usable from 0 to over 1MH Z to which feedback is added to control its overall response characteristic i.e. gain and bandwidth. The op-amp exhibits the gain down to zero frequency. Such direct coupled (dc) amplifiers do not use blocking (coupling and by pass) capacitors since these would reduce the amplification to zero at zero frequency. Large by pass capacitors may be used but it is not possible to fabricate large capacitors on a IC chip. The capacitors fabricated are usually less than 20 pf. Transistor, diodes and resistors are also fabricated on the same chip. Differential Amplifiers: Differential amplifier is a basic building block of an op-amp. The function of a differential amplifier is to amplify the difference between two input signals. How the differential amplifier is developed? Let us consider two emitter-biased circuits as shown in fig. 1. Fig. 1 The two transistors Q1 and Q2 have identical characteristics. The resistances of the circuits are equal, i.e. RE1 = R E2, RC1 = R C2 and the magnitude of +VCC is equal to the magnitude of �VEE. These voltages are measured with respect to ground. To make a differential amplifier, the two circuits are connected as shown in fig. 1. The two +VCC and �VEE supply terminals are made common because they are same. The two emitters are also connected and the parallel combination of RE1 and RE2 is replaced by a resistance RE. The two input signals v1 & v2 are applied at the base of Q1 and at the base of Q2.