James Short and the Eclipses of 1908, 1910 and 1911

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eclipse Science Results: Past and Present

The Last Total Solar Eclipse of the Mil lennium in Turkey ASP Conference Series Vol W Livingston and A Ozgu c eds Eclipse Science Results Past and Present W Livingston National Solar Observatory NOAO PO Box Tucson AZ USA S Koutchmy Institut dAstrophysique de ParisCNRS Bis Boulevard Arago F Paris France Abstract We review the signicant advances that havebeenachieved by eclipse exp eriments First we note the anomaly that the corona was not even seen until relatively mo dern times Beginning in whitelight WL photographs suggested structures that must have b een dominated by magnetic elds This led to the disco very of surface magnetism in sunsp ots by Hale in the rst detection of cosmic magnetism Deli cate direct photographic observations conrmed the b ending of starlight near the eclipsed Sun as predicted by Einsteins General Theory of Rela tivity Chromospheric ash sp ectra indicated that the outer layer of the Sun was much hotter than the underlying photosphere leading to non lo cal thermo dynamic equilibrium concepts and the idea of various me chanical and wave pro cesses to maintain it Decades have been devoted to understanding the corona Discovery of its million degree plus tem p erature and guring howto heat it how co ol prominences can coexist within it all are topics to which eclipse observations havecontributed Totality without a Corona Eclipses have b een chronicled for o ver years but the corona escap ed b eing noticed until mo dern times The single exception Leonis Deaconis in AD mentions a certain dull and feeble glow -

EPSC2015-913, 2015 European Planetary Science Congress 2015 Eeuropeapn Planetarsy Science Ccongress C Author(S) 2015

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 10, EPSC2015-913, 2015 European Planetary Science Congress 2015 EEuropeaPn PlanetarSy Science CCongress c Author(s) 2015 The “Station de Planétologie des Pyrénées” (S2P), a collaborative science program in the course of a long history at Pic du Midi observatory. F. Colas (1), A. Klotz (2), F. Vachier (1), M. Birlan (1), B. Sicardy (3), J. Lecacheux (3), M. Antuna (6), R. Behrend (4), C. Birnbaum (6), G. Blanchard (6), C. Buil (4,5), J. Caquel (6), M. Castets (5), C. Cavadore (4), B. Christophe (6), F. Cochard (4), J.L. Dauvergne (6), F. Deladerriere (6), M. Delcroix (6), V. Denoux (4), J.B. DeVanssay (6), P. Devechere (6), P. Dupouy (5), E. Frappa (6), S. Fauvaud (5), B. Gaillard (6), F. Jabet (6), M. Lavayssiere (6), T. Legault (6), A. Leroy (5), A. Maury (6), M. Meunier (6), C. Pellier (6), C. Rinner (4), E. Rolland (6), O. Stenuit (6), I. Testar (6), P. Thierry (4), O. Thizy (4), B. Tregon (5), F. Vaissiere (4), S. Vauclair (6), C. Viladrich (6), C. Angeli (6), J.E. Arlot (1), M. Assafin (28), D. Bancelin (1), D. Baratoux (29), N. Barrado-Izagirre (8), M.A. Barucci (3), L. Beauvalet (9), P. Bendjoya (13), J. Berthier (1), N. Biver (3), D. Bockelee-Morvan (3), D. Berard (3), S. Bouley (10), S. Bouquillon (9), P. Bourget (11), F. Bragas- Ribas (7), J. Camargo (7), B. Carry (1), S. Chevrel (2), M; Chevreton, (3), P. Colom (3), J. Crovisier (3), J. Demars (1), R. Despiau (2), P. Descamps (1), N. Dolez (2), A. -

February 2014 the Newsletter of the Barnard-Seyfert Astronomical Society

February TheECLIPSE 2014 The Newsletter of the Barnard-Seyfert Astronomical Society From the President Next Membership Meeting: February 19, 2014, 7:30 pm Cumberland Valley Professionals vs. amateurs… the distinctions have Girl Scout Council Building blurred over the years in different ways. There was 4522 Granny White Pike a time when mere money could get you the gear to have a professional observatory. Many large Program Topic: telescopes were built with private funds by Joshua Emery - interested individuals… think of William Hershel and the “Don Quixote” object (details on page 5) Percival Lowell. Then amateurs were pushed aside by large scale photography and the truly large telescopes that needed institutions to care for and run them… like the Mt. Wilson and Mt. Palomar observatories. Expensive ccd cameras, exotic cooling, the computing power needed even after In this Issue: glass plates were replaced put meaningful observations out of reach of amateurs. Then with President’s Message 1 the advent of the personal computer and digital Observing Highlights 2 cameras, the playing field was leveled by computers that anyone could own, low noise digital Happy Birthday, cameras and powerful software. Bernard Ferdinand Lyot by Robin Byrne 3Today, you can take the hobby or second life in astronomy as far as you wish, in partnership with Board Meeting Minutes January 8, 2014 6professionals. On any given clear night, enthusiasts around the world are recording not just pretty Membership Meeting Minutes pictures, but data. Our sheer numbers allow us to January 15, 2013 9look at things in depth and at a frequency not possible if we depended just on the large research Membership Information 10 telescopes. -

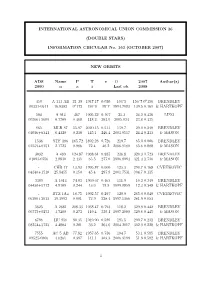

CIRCULAR No. 163 (OCTOBER 2007)

INTERNATIONAL ASTRONOMICAL UNION COMMISSION 26 (DOUBLE STARS) INFORMATION CIRCULAR No. 163 (OCTOBER 2007) NEW ORBITS ADS Name P T e (2000) 2007 Author(s) ®2000± n a i ! Last ob. 2008 450 A 111 AB 21y38 1947.17 0.020 104±5 156±7 000156 BRENDLEY 00321-0511 16.8382 000172 150±0 18±7 1994.7083 139.5 0.161 & HARTKOPF 504 A 914 467. 1905.32 0.107 35.3 24.2 0.436 LING 00366+5609 0.7709 0.468 118.2 291.9 2005.034 23.8 0.435 865 MLR 87 55.97 2020.45 0.513 139.7 29.0 0.240 BRENDLEY 01036+6341 6.4320 0.238 145.1 246.4 2003.9517 24.4 0.233 & MASON 1538 STF 186 165.72 1892.28 0.726 219.7 65.0 0.906 BRENDLEY 01559+0151 2.1723 0.986 72.4 40.2 2006.9180 65.6 0.888 & MASON 3032 A 469 124.87 1968.61 0.885 236.8 320.3 1.723 BRENDLEY 04093-0756 2.8830 2.435 65.5 277.0 1996.8984 321.4 1.736 & MASON - CHR 17 13.93 1995.87 0.600 125.3 290.7 0.168 CVETKOVIC 04340+1510 25.8455 0.150 45.4 297.9 2001.7531 304.7 0.135 3389 A 1014 74.83 1969.67 0.465 111.9 10.2 0.349 BRENDLEY 04430+5712 4.8109 0.244 13.0 78.8 1999.8859 12.3 0.348 & HARTKOPF - BTZ 1Aa 18.75 1992.57 0.297 120.9 265.0 0.040 CVETKOVIC 06290+2013 19.1992 0.081 72.9 228.4 1997.1366 281.9 0.053 5625 A 2681 208.33 1938.47 0.793 118.2 329.9 0.442 BRENDLEY 06575+0253 1.7280 0.273 119.4 339.1 1997.2000 329.6 0.445 & MASON 6796 HU 856 80.35 1949.90 0.589 185.5 299.7 0.231 BRENDLEY 08254+3723 4.4804 0.201 36.2 263.6 2004.2017 302.0 0.228 & HARTKOPF 7555 AC 5 AB 77.82 1957.65 0.736 194.7 53.1 0.585 BRENDLEY 09525-0806 4.6261 0.397 141.1 303.3 2006.3199 51.9 0.582 & HARTKOPF 1 NEW ORBITS (continuation) ADS Name P T e (2000) 2007 Author(s) ®2000± n a i ! Last ob. -

Observation of Venus and Mercury Transits from the Pic-Du-Midi Observatory

MEETING VENUS C. Sterken, P. P. Aspaas (Eds.) The Journal of Astronomical Data 19, 1, 2013 Observation of Venus and Mercury Transits from the Pic-du-Midi Observatory Guy Ratier 43 rue des Longues All´ees, F-45800 Saint-Jean-de-Braye, France Sylvain Rondi Soci´et´eAstronomique de France, 3 rue Beethoven, F-75016 Paris France Abstract. The Pic-du-Midi, on the French side of the Pyr´en´ees, became a state observatory in the summer of 1882. The first major astronomical event to be observed was the Venus transit of 6 December 1882. Unfortunately this attempt by the well-known Henry brothers was unsuccessful due to bad weather conditions. During the twentieth century, the Pic-du-Midi became famous for the quality of its solar and planetary observations. In the sixties, Jean R¨osch decided to use this experience to monitor the transits of Mercury. The objective was not to measure the parallax, but to determine the diameter of the planet in order to confirm its high density. Observations were made using a photometric method – the Hertzsprung method – during the transits of 1960, 1970 and 1973. The pioneer work of Ch. Boyer on the rotation of the Venus atmosphere as well as some experiments involving Lyot coronographs are also noteworthy. A Venus transit was finally observed on 8 June 2004 with a new CCD camera, providing a significant contribution to the model of the Venus mesosphere. This opened the field for new observations in 2012. 1. Early days of the Pic-du-Midi Observatory The site of the “Pic-du-Midi de Bigorre”, on the forefront of the Pyr´en´ees, has been known since ages as an ideal location to carry out astronomical observations. -

Istros 2013 Proceedings Download Link

Proceedings of the ISTROS 2013 International Conference Editors: M. Veselský and M. Venhart INSTITUTE OF PHYSICS, SLOVAK ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Bratislava 2015 ISBN 978-80-971975-0-6 Dear participants, we bring to you the proceedings of the conference ISTROS (Isospin, STructure, Reactions and energy Of Symmetry), which took place in the period between Sept 23 – - for meeting of Sept 27 2013 in Častá withPapiernička. experimental The declared and theoretical aim of theaspects conference of physics was of to exotic provide nuclei platform and states of nuclear international and Slovak scientists, active in the field of nuclear physics, specifically dealing matter, and we hope that this aim was fulfilled. presentationDuring the conference, is represented 36 invited in this and proceedings contributed in talks the formwere ofpresented, short artic coveringles, while the otheropen participantsproblems in decidedthe physics to abstain of exotic from nuclei this and thusof the their states presentations of nuclear matter.are represented Part of these only by their abstracts. In general, present time appears to modify traditional procedures and one of the victims are the conference proceedings in their habitual form. We are still convinced complementthat publication the of proceedi proceedingsngs iswith a part a briefof our summaryduties as organizersof history as of a servicenatural to sciences participants and and with this in mind we bring to you these proceedings. Besides the contributed articles, we technology in the territory of Slovakia, which bring some interesting facts about the progress of scientific and technical knowledge in Slovakia. - discussing interesting physics, and thus we aim to bring the second edition of the ISTROS As far as we can judge, you had a productive time at Častá Papiernička, spent meaningfully conference in the near future. -

1 Accepted for Publication in the Journal of the British

1 David Elijah Packer: cluster variables, meteors and the solar corona Jeremy Shears Abstract David Elijah Packer (1862-1936), a librarian by profession, was an enthusiastic amateur astronomer who observed from London and Birmingham. He first came to the attention of the astronomical community in 1890 when he discovered a variable star in the globular cluster M5, only the second periodic variable to be discovered in a globular cluster. He also observed meteors and nebulae, on one occasion reporting a brightening in the nucleus of the galaxy M77. However, his remarkable claims in 1896 that he had photographed the solar corona in daylight were soon shown to be flawed. Biographical sketch David Elijah Packer was born in Bermondsey, London, in 1862 April (1) the eldest child of Edward Packer (1820-1896) and Emma (Bidmead) Packer (1831-1918) (2). David attended the Free Grammar School of Saint Olave and Saint John at Southwark, where he performed well, especially in arithmetic, algebra and general mathematics (3). Edward Packer was a basket maker, as was his father and grandfather before him, the Packer family originally coming to London from Thanet, in Kent. The English basket-making industry was in decline during the second half of the nineteenth century due to the availability of cheaper imports from the continent. In spite of this, Edward was still in business in 1881, but the prospects for his son continuing in a trade that had made a living for generations of his ancestors were probably limited (4). Thus at the age of 18 we find David Elijah Packer working as an Oilman’s Assistant, supplying fuel for the oil lamps of London (5). -

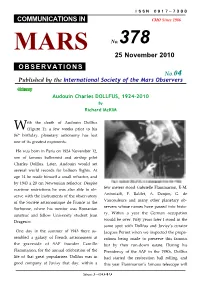

Communications in Observations

ISSN 0917-7388 COMMUNICATIONS IN CMO Since 1986 MARS No.378 25 November 2010 OBSERVATIONS No.04 PublishedbytheInternational Society of the Mars Observers Audouin Charles DOLLFUS, 1924-2010 By Richard McKIM ith the death of Audouin Dollfus W(Figure 1), a few weeks prior to his 86th birthday, planetary astronomy has lost one of its greatest exponents. He was born in Paris on 1924 November 12, son of famous balloonist and airship pilot Charles Dollfus. Later, Audouin would set several world records for balloon flights. At age 14 he made himself a small refractor, and by 1943 a 20 cm Newtonian reflector. Despite few meters stood Gabrielle Flammarion, E‐M. wartime restrictions he was also able to ob‐ Antoniadi, F. Baldet, A. Danjon, G. de serve with the instruments of the observatory Vaucouleurs and many other planetary ob‐ of the Société astronomique de France at the servers whose names have passed into histo‐ Sorbonne, where his mentor was Romanian ry. Within a year the German occupation amateur and fellow University student Jean would be over. Fifty years later I stood in the Dragesco. same spot with Dollfus and Juvisy’s curator One day in the summer of 1943 there as‐ Jacques Pernet when we inspected the prepa‐ sembled a galaxy of French astronomers at rations being made to preserve this famous the graveside of SAF founder Camille butbythenrun‐down estate. During his Flammarion, for the annual celebration of the Presidency of the SAF in the 1980s, Dollfus life of that great populariser. Dollfus was in had started the restoration ball rolling, and goodcompanyatJuvisythatday:withina this year Flammarion’s famous telescope will Ser3-0049 CMO No. -

Encke's Minima and Encke's Division in Saturn's A-Ring

ENCKE’S MINIMA AND ENCKE’S DIVISION IN SATURN’S A-RING Pedro Ré http://astrosurf.com/re When viewed with the aid of a good quality telescope Saturn is undoubtedly one of the most spectacular objects in the sky. Many amateur astronomers (including the author) say that their first observation of Saturn turned them on to astronomy. Saturn’s rings are easily visible with a good 60 mm refractor at 50x. The 3D appearance of this planet is what makes it so interesting. Details in the rings can be seen during moments of good seeing. The Cassini division (between ring A and B) is easily visible with moderate apertures. The Encke minima and Encke division are more difficult to observe and require large apertures and telescopes of excellent optical quality. These two features can be observed in Saturn’s A-Ring. The Encke minima consists of a broad, low contrast feature located about halfway out in the middle of the A-Ring. The Encke division is a narrow, high contrast feature located near the outer edge of the A-Ring. Unlike the Encke minima, the Encke division is an actual division of the ring (Figure 1). Figure 1- Saturn near Opposition on June 11, 2017. D. Peach, E. Kraaikamp, F. Colas, M. Delcroix, R. Hueso, G. Thérin, C. Sprianu, S2P, IMCCE, OMP. The Encke division is visible around the entire outer A ring. Astronomy Picture of the Day (20170617) https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap170617.html 1 Galileo Galilei observed the disk Saturn for the first time using one of his largest refractor. -

Solar Surveillance with CLIMSO: Instrumentation, Database and On-Going Developments

J. Space Weather Space Clim. 2020, 10,47 Ó F. Pitout et al., Published by EDP Sciences 2020 https://doi.org/10.1051/swsc/2020039 Available online at: www.swsc-journal.org Topical Issue - Space Weather Instrumentation TECHNICAL ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS Solar surveillance with CLIMSO: instrumentation, database and on-going developments Frédéric Pitout1,*, Laurent Koechlin1, Arturo López Ariste1, Luc Dettwiller2, and Jean-Michel Glorian1 1 IRAP, Université Toulouse 3, CNRS, CNES, 9 Avenue du Colonel Roche, BP 44346, 31028 Toulouse Cedex 4, France 2 Higher Education Section of Lycée Blaise Pascal, 36 Avenue Carnot, 63037 Clermont-Ferrand Cedex, France Received 1 May 2020 / Accepted 27 July 2020 Abstract – CLIMSO is a suite of solar telescopes installed at Pic du Midi observatory in the southwest of France. It consists of two refractors that image the full solar disk in Ha and CaII K, and two coronagraphs that capture the prominences and ejections of chromospheric matter in Ha and HeI. Synoptic observations are carried out since 2007 and they follow those of previous instruments. CLIMSO, together with its predecessors, offer a temporal coverage of several solar cycles. With a direct access to its images, CLIMSO contributes to real time monitoring of the Sun. For that matter, the national research council for astrophysics (CNRS/INSU) has labelled CLIMSO as a national observation service for “surveillance of the Sun and the terrestrial space environment”. Products, under the form of images, movies or data files, are available via the CLIMSO DataBase. In this paper, we present the current instrumental configuration; we detail the available products and show how to access them; we mention some possible applications for solar and space weather; and finally, we evoke developments underway, both numerical to valorise our data, and instrumental to offer more and better capabilities. -

Gerard Peter Kuiper

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES G ERARD PETER K UIPER 1905—1973 A Biographical Memoir by D A L E P . CRUIKSHANK Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1993 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. GERARD PETER KUIPER December 7, 1905-December 24, 1973 BY DALE P.CRUIKSHANK OW DID THE SUN and planets form in the cloud of gas H and dust called the solar nebula, and how does this genesis relate to the formation of other star systems? What is the nature of the atmospheres and the surfaces of the planets in the contemporary solar system, and what have been their evolutionary histories? These were the driv- ing intellectual questions that inspired Gerard Kuiper's life of observational study of stellar evolution, the properties of star systems, and the physics and chemistry of the Sun's family of planets. Gerard Peter Kuiper (originally Gerrit Pieter Kuiper) was born in The Netherlands in the municipality of Haringcarspel, now Harenkarspel, on December 7, 1905, son of Gerrit and Antje (de Vries) Kuiper. He died in Mexico City on December 24, 1973, while on a trip with his wife and his long-time friend and colleague, Fred Whipple. He was the first of four children; his sister, Augusta, was a teacher before marriage, and his brothers, Pieter and Nicolaas, were trained as engineers. Kuiper's father was a tailor. Young Kuiper was an outstanding grade school student, but for a high school education he was obliged to leave his small town and go to Haarlem to a special institution that would lead him to a career as a primary school teacher. -

French Astronomers, Visual Double Stars and the Double Stars Working Group of the Société Astronomique De France Edgar J

French astronomers, visual double stars and the double stars working group of the Société Astronomique de France Edgar J. Soulié Société Astronomique de France 3, rue Beethoven 75016 PARIS France 1. A long tradition : The discovery of the orbital motion of visual double stars by William Herschel aroused the interest of French astronomers for the observation of double stars and the computation of their orbits at the beginning of the XIX-th century. Thus, the first orbit determination, pertaining to the binary ksi Ursae Majoris, was made by Félix Savary in 1827 (1). About twenty years later, Antoine Yvon Villarceau, whose career was surprisingly varied (see his biography in ref. 2), proposed an elegant method for the determination of the apparent orbit and an algorithm to deduce the real orbit (3). Camille Flammarion, the founder of the Société Astronomique de France whose biography was published in 1994 (4), observed visual double stars, calculated orbits and published in 1878 a book entitled "Catalogue des étoiles doubles et multiples en mouvement relatif certain..." (5). Guillaume Bigourdan, inventor of a method for setting an equatorial instrument into an appropriate position which bears his name, observed them between 1880 and 1895, and analyzed the personal factor in the measurement process (6). In the second volume of his treatise on stellar astronomy (7), Charles André devoted seven chapters to binary stars, in which the knowledge of the time on the various categories of double stars are gathered. In particular, methods for orbit determination are given for each category. In this treatise, he published among other things the list of binaries, the orbits of which were known in 1900.