Evaluating the Initial Rice Cultivation Environment on the Korean Peninsula

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KIM, JONG SOOK (B

9 E 82nd St Ste 3A (btwn Fifth & Madison) New York, NY 10028-0316 t 212 734 1490 | [email protected] | www.kangcollection.com COLLEC T ION KO R E A N AR T KIM, JONG SOOK (b. 1968 - ) Lives and Works in Seoul, Korea EDUCATION Ph. D Fine Arts, Graduate School of Hong-ik University, Seoul, Korea MFA Hong-ik University, Seoul, Korea BFA Hong-ik University, Seoul, Korea SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITION 2016 Sparkling Forever, Superior Gallery, Seoul, Korea Spectacle or Phantasmagoria, Rae Gallery, Busan, Korea 2015 Artificial Landscape, Shinhan Gallery, Seoul, Korea 2014 The Brilliant Day, Lotte Avenuel, Seoul, Korea Artificial Landscape, AramNuri Museum, Goyang, Korea 2013 Artificial Landscape, Kwanhoon Gallery, Seoul, Korea 2012 Artificial Landscape, Gail Museum, Gapyung, Korea 2011 Artificial Landscape, Kwanhoon Gallery, Seoul, Korea 2009 Artificial Landscape, Noam Gallery, Seoul, Korea 2008 Artificial Landscape, Geneva Palexpo, Geneva, Swiss 2007 Crystallized-from Painting to Drawing, Insa Art Center, Seoul, Korea 2006 Crystal Nostalgia, CJ Gallery, San Diego, CA 2005 The Nostalgia for Myth, White Box Gallery, Los Angeles, CA SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITION 2016 Color-ing, Grimson Gallery, Seoul, Korea Si-Son-Yu-Do, Grimson Gallery, Seoul, Korea 2015 Walking with Art, Hoseo University Museum, Asan, Korea Art Central HongKong, Harbourfront, HongKong, China The Present, Owlim Museum, Asan, Korea Representation of Representation, Interpretation of Interpretation, Now Gallery, Seoul, Korea 2014 Art and Ideals, Ewha Womans University Museum, Seoul, -

Packaged Food in South Korea

International Markets Bureau MARKET ANALYSIS REPORT | MARCH 2012 Packaged Food in South Korea Source: Shutterstock Source: Shutterstock Packaged Food in South Korea EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INSIDE THIS ISSUE South Korea’s packaged food market is ranked 15th largest in Executive Summary 2 the world, with a value of US$20.0 billion in 2010. Rising incomes have driven market growth and pushed consumer Country Profile 3 agri-food imports to US$5.7 billion. At the same time, consumer demand has evolved with recent socioeconomic Consumer Profile 4 changes. An aging population, growing income disparity, and Consumer Trends 5 busier lifestyles have generated interest in health and wellness and convenience-oriented food products. These Major Subsectors 7 developments have fostered the trends of product premiumization and value consciousness. Market Structure 9 The packaged food market is fairly concentrated, with major Trade 9 South Korean manufacturers controlling significant portions of their respective subsectors. The retail sector that imports and Distribution Channels 11 distributes packaged food is similarly concentrated. Hypermarkets and supermarkets distribute the vast majority of Key Retailers 12 packaged food and compete against brand names with their Distribution Trends 12 own private labels. Canadian firms thus face entry barriers, but also have opportunities to supply distributors and Opportunities in Packaged Food 13 capitalize on present market trends. Challenges in Packaged Food 14 Despite the considerable growth in this market, Canadian exports have fallen in recent years. Competitors, especially Conclusion 14 the United States and Brazil, are increasingly gaining market Bibliography 15 share. However, Canada remains the eighth-largest processed food exporter to South Korea, and key exports include meat, cereals, and fish and seafood. -

A Collaborative Trans-Regional R&D Strategy for the South Korea Green New Deal to Achieve Future Mobility

sustainability Article A Collaborative Trans-Regional R&D Strategy for the South Korea Green New Deal to Achieve Future Mobility Doyeon Lee and Keunhwan Kim * Division of Data Analysis, Korea Institute of Science and Technology Information (KISTI), 66, Hoegi-ro, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul 02456, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, South Korea is moving to establish a national industry strategy to reduce regional inequalities within the country through the Green New Deal. Thus, it is important to closely integrate the aim of reducing greenhouse gas emissions from the Green New Deal with that of reducing deepening regional inequality from the Regionally Balanced New Deal. To accomplish these dual aims, this study provides a collaborative trans-regional R&D strategy and a precise framework with three key dimensions: regional, technological, and organizational. We demonstrate that future mobility is the most important project of the Green New Deal, comprising 1963 nationally funded projects worth USD 1285.4 million. We also illustrate the level of government investment in nationally funded research projects related to future mobility for 17 different regions and seven different technology clusters related to future mobility, and determine which research organizations played an important role in each cluster for all 17 regions between 2015 and 2020. Our results indicate that the capital region and Daejeon have high innovation capability in many future mobility-related research fields, whereas some regions have capabilities in specific research fields such as hydrogen infrastructure, indicating their relative competitiveness. Citation: Lee, D.; Kim, K. -

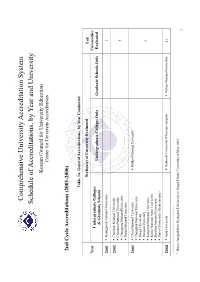

Schedule of Accreditations, by Year and University

Comprehensive University Accreditation System Schedule of Accreditations, by Year and University Korean Council for University Education Center for University Accreditation 2nd Cycle Accreditations (2001-2006) Table 1a: General Accreditations, by Year Conducted Section(s) of University Evaluated # of Year Universities Undergraduate Colleges Undergraduate Colleges Only Graduate Schools Only Evaluated & Graduate Schools 2001 Kyungpook National University 1 2002 Chonbuk National University Chonnam National University 4 Chungnam National University Pusan National University 2003 Cheju National University Mokpo National University Chungbuk National University Daegu University Daejeon University 9 Kangwon National University Korea National Sport University Sunchon National University Yonsei University (Seoul campus) 2004 Ajou University Dankook University (Cheonan campus) Mokpo National University 41 1 Name changed from Kyungsan University to Daegu Haany University in May 2003. 1 Andong National University Hanyang University (Ansan campus) Catholic University of Daegu Yonsei University (Wonju campus) Catholic University of Korea Changwon National University Chosun University Daegu Haany University1 Dankook University (Seoul campus) Dong-A University Dong-eui University Dongseo University Ewha Womans University Gyeongsang National University Hallym University Hanshin University Hansung University Hanyang University Hoseo University Inha University Inje University Jeonju University Konkuk University Korea -

College Codes (Outside the United States)

COLLEGE CODES (OUTSIDE THE UNITED STATES) ACT CODE COLLEGE NAME COUNTRY 7143 ARGENTINA UNIV OF MANAGEMENT ARGENTINA 7139 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF ENTRE RIOS ARGENTINA 6694 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF TUCUMAN ARGENTINA 7205 TECHNICAL INST OF BUENOS AIRES ARGENTINA 6673 UNIVERSIDAD DE BELGRANO ARGENTINA 6000 BALLARAT COLLEGE OF ADVANCED EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 7271 BOND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7122 CENTRAL QUEENSLAND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7334 CHARLES STURT UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6610 CURTIN UNIVERSITY EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6600 CURTIN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 7038 DEAKIN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6863 EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7090 GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6901 LA TROBE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6001 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6497 MELBOURNE COLLEGE OF ADV EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 6832 MONASH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7281 PERTH INST OF BUSINESS & TECH AUSTRALIA 6002 QUEENSLAND INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 6341 ROYAL MELBOURNE INST TECH EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6537 ROYAL MELBOURNE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 6671 SWINBURNE INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 7296 THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA 7317 UNIV OF MELBOURNE EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7287 UNIV OF NEW SO WALES EXCHG PROG AUSTRALIA 6737 UNIV OF QUEENSLAND EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 6756 UNIV OF SYDNEY EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7289 UNIV OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA EXCHG PRO AUSTRALIA 7332 UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE AUSTRALIA 7142 UNIVERSITY OF CANBERRA AUSTRALIA 7027 UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES AUSTRALIA 7276 UNIVERSITY OF NEWCASTLE AUSTRALIA 6331 UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND AUSTRALIA 7265 UNIVERSITY -

Transition from the Prehistoric Age to the Historic Age: the Early Iron Age on the Korean Peninsula

Transition from the Prehistoric Age to the Historic Age: The Early Iron Age on the Korean Peninsula KisUNg Y i introduction The appearance of metal objects in the prehistoric period was of great sig- nificance. As iron implements became accepted as common tools used in everyday life and agricultural productivity increased, complex societies appeared and eventually developed into states. For this reason, archaeologists divide prehistoric times into pe- riods based on the material attributes of new technologies. The periods that have been defined for most regions of the world are not much different from those used in the archaeology of Korea. Korean archeologists define the Early iron Age as the period from 300 b.c. to 100 b.c. during which cast ironware was distributed by the Yan (燕) dynasty. Al- though ironware is the most significant material marker of this cultural phase, the mass production of iron objects in general and ironware in particular was not fully realized during this period ( KAs 2010 : 123). situated between the Bronze Age and the Proto– Three Kingdoms period, the Early iron Age is culturally significant because it serves as the transitional period between the Prehistoric and Historic eras. Despite this sig- nificance, the cultural characteristics of the Early iron Age, its area of origin, and its relationship with earlier indigenous cultures have yet to be explained. This article examines the concept of an “Early iron Age” in Korea and the cultural characteristics that define it. it also reviews various issues and debates within studies on the Early iron Age. For instance, in Korea the Early iron Age is defined materially primarily by the presence of Jeomtodae (clay-striped) pottery and slender bronze daggers. -

Gwangju-Jeonnam KOTESOL Chapter Reports the Archive

Gwangju-Jeonnam KOTESOL Chapter Reports The Archive Contents Chapter Reports 2004 – 2011 KOTESOL in Action, The English Connection (TEC) Chapter Reports 2011 – 2013 KOTESOL Chapter News, TEC News Gwangju-Jeonnam Chapter Presidents 2004 Spring – 2005 November Maria Lisak 2005 November – 2006 March Scott Jackson 2006 March – 2008 March 15 Dr. Yeon-seong Park 2008 March 15 – 2009 November Adriane Moser Geronimo 2009 November – 2016 November Dr. David E. Shaffer 2016 November – 2017 November William Mulligan 2017 November – 2018 November Lindsay Herron 2018 November – Bryan Hale regions, and would then spread out to JEOLLA CHAPTER SEOUL CHAPTER those areas without a KOTESOL presence. At a later stage, we will cultivate speaking links with sister organizations and by Allison Bill by Tory Thorkelson governmental entities. To this end Dr. Robert Dickey has expressed interest in Perhaps the title for this section should As winter approaches, The Seoul chapter KTT giving presentations in the southern be Jeonbuk/Jeonnam Chapters (plural). By is gearing up for our regional conference part of the nation, possibly as early as the time you are reading this TEC, a in May, 2004. After a hiatus of 3 months January. Paul Mead has also expressed decision should have been made about for summer vacation, the YL SIG and the interest in doing this for the Pusan area, whether or not to split Jeolla Chapter into 11th KOTESOL International Conference, and Dr. Steve Garrigues will speak under two chapters: a Jeonju-Jeonbuk Chapter our monthly meetings resumed with a the KTT banner to a group in Taegu. So, in the north and a Gwangju-Jeonnam presentation on November 15th by our new we are off to a good start in 2004! Chapter in the south. -

Evaluation of the Structure of Urban Stormwater Pipe Network Using Drainage Density

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 10 July 2018 doi:10.20944/preprints201807.0168.v1 Article Evaluation of the Structure of Urban Stormwater Pipe Network Using Drainage Density Jinwoo Lee 1, Gunhui Chung 2,*, Heeseong Park 3 and Innjoon Park 4 1 Master student, Dept. of Civil Engineering, Hoseo University, Asan-si, Chungcheongnam-do, South Korea; [email protected] 2 Corresponding author, Assistant professor, Dept. of Civil Engineering, Hoseo University, Asan-si, Chungcheongnam-do, South Korea; [email protected] 3 Research Fellow, Department of Land, Water and Environment Research, Korea Institute of Civil engineering and building Technology, South Korea; [email protected] 4 Professor, Dept. of Civil Engineering, Hanseo University, Seosan-si, Chungcheongnam-do, South Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-41-540-5794 Abstract: In mega cities such as Seoul in South Korea, it is very important to protect the city from the flooding even for the short time of period due to the enormous amount of economic damage. In impervious area of the city, stormwater pipe network is commonly applied to discharge rainfall to the outside of catchment. Therefore, the stormwater pipe network in urban catchment should be carefully designed to discharge the runoff quickly and efficiently. In this study, different types of structures in stormwater pipe network were evaluated using the relationship between the peaks rainfall and runoff in urban catchments in South Korea. More than 400 historical rainfall events were applied in five urban catchments to estimate peak runoff from different type of network structures. Linear regression analysis was implemented to estimate peak runoffs. -

July 31(Sun) - August 6 (Sat), 2016 Daejeon Convention Center, Daejeon, Korea

1st Announcement July 31(Sun) - August 6 (Sat), 2016 Daejeon Convention Center, Daejeon, Korea Hope & Happiness: The role of home economics in the pursuit of hope & happiness for individuals and communities now and in the future Sponsored by DAEJEON METROPOLITAN CITY KOREA Invitation It gives me great pleasure to invite you to the 23rd IFHE World Congress 2016. Whether you are a passionate home economics professional or an interested allied professional, we invite you to participate in the global conversation that is IFHE World Congress. As indicated by our theme for 2016 - Hope and Happiness: The role of home economics in the pursuit of hope and happiness for individuals and communities now and in the future - we as home economists recognise that our profession is a key component of hope and happiness - critical for the wellbeing of individuals, families and communities. We also seek creative and innovative ways to communicate this message widely and effectively. As the only worldwide organisation concerned with home economics and consumer studies, it is imperative that IFHE seizes every opportunity to speak in full voice. World Congress gives us that opportunity. Since 1908, professionals, scholars and educators in home economics and allied fields have come together every four years to learn, share and inspire. Our consultative status with the United Nations and the Council of Europe gives us so much potential to extend congress outcomes and to see our resolutions put into action. We are pleased and excited to be staging IFHE World Congress in the Asian region for the first time since 2004. Daejeon, Korea, has built a reputation for the hosting of global conferences and is a hub for technology, education, research and development. -

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools KENYA 002859 Egerton

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools KENYA 002859 Egerton Univ 005018 Kenya Science Teachers Coll 000745 Kenyatta Univ Col 000743 Moi Univ 003189 Ngandu Girls' High School 000744 Royal Tech Col East Africa 046917 Strathmore College 000744 Univ Col Nairobi 000744 Univ Nairobi KOREA, DEMOCRATIC PPL'S REPUBLIC 001214 Kim Chaek Univ Tech 001213 Kim Il Sung Univ 001215 Pyongyang Univ Medicine KOREA, REPUBLIC OF 002120 Ajou Univ 002869 Anyang Univ 004303 Bae Myeong Hs 000366 Busan Na Univ. 002818 Busan Women'S University 002213 Catholic Medical Col 002952 Catholic University Of Korea 004062 Chang-An Junior College 002119 Cheju Na Univ 000367 Cho Sun Dae Hag Gyo 000367 Cho Sun Univ 000368 Chon Nam Dae Hag Gyo 046336 Chongju University 002186 Chongshin Col 000368 Chonnam Na Univ 000371 Choong Nam Na Univ 000371 Choonnam National University 046339 Chugye University for Arts 000369 Chung Ang Dae Hag Gyo 000369 Chung Ang Univ 000370 Chung Bug Dae Hag 000371 Chung Nam Dae Hag Gyo 000370 Chungbuk Na Univ 004696 Daewon Foreign Language Hs 004696 Daewon Girls' Sr Hs 004696 Daewon Jr Hs 004696 Daewon Sr Hs 000372 Dan Gug Dae Hag Gyo 000372 Dankook Univ 000373 Dong A Dae Hag Gyo 000373 Dong A Univ 000374 Dong Guk Dae Hag Gyo 002947 Dongdok Yoja Dae Hak 002947 Dongduck Women'S University 002947 Dongduk Women'S University International Schools 000374 Dongguk University 002245 Duksung Womens Col 000392 Ewha Womens Univ 000392 Ewha Womens University 002808 Gangnam Social Welfare College 000375 Go Lyeo Dae Hag Gyo 000377 Gyeong Sang Dae Hag Gyo 000377 Gyeong -

Executive Director's Asia Trip Confirms OMSC's Enduring Calling

Executive Director’s Asia Trip Confirms OMSC’s Enduring Calling On March 3, I embarked on my first international trip on behalf of OMSC. With invaluable practical support from the Korean Research Institute for Mission's Dr. Steve Moon (photo at right) and Chun Lee, his colleague and recent OMSC alumnus, a very busy agenda provided many chances to speak with alumni, missionaries, church leaders, seminary administrators and professors, and students. Starting and ending in Seoul, I also visited Cheonan, Gwangju, and Daejeon over the next 18 days, preaching, lecturing, sharing about OMSC’s work, and getting to know colleagues in God’s mission at KRIM, Sarang Church, Yonsei University Church and Chapel, Presbyterian University and Theological Seminary, Hoseo University and Theological Seminary, Honam University and Theological Seminary, First Presbyterian Church Daejeon, Torch Trinity University, Jiguchon Church, and Asian Mission. Everywhere I went, I received a warm and gracious welcome, meeting old friends of OMSC and many new ones. In Seoul, I visited the Yanghwajin Foreign Missionary Cemetery and adjacent 100th Anniversary Memorial Church, whose volunteers maintain the cemetery and serve as tour guides for visitors from all over Korea and the world. I was moved to stand at the grave of Dr. Horace Underwood III, who was a great personal encouragement to me after Carol and I were appointed by the PC (USA) in 1988 as Mission Co- workers to Japan. Also, the grave of Gaichi Soda (1867–1962), a Japanese man who had a ministry for Korean orphans, is a powerful symbol of hope for peace and reconciliation between neighboring countries who share a troubled history. -

JIHWAN HWANG Strategy and Entrepreneurship Department of Management Raymond J

Curriculum Vitae (Revised October 29, 2020) JIHWAN HWANG Strategy and Entrepreneurship Department of Management Raymond J. Harbert College of Business Auburn University 405 W. Magnolia Ave. Auburn, AL 36849 Phone: (334) 750-5829 E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. Strategy and Entrepreneurship, expected Spring 2022 Auburn University, Auburn, AL Primary Area: Strategy and Entrepreneurship M.S. Human Resources Management, May 2010 Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ Primary Area: Organizational Behavior B.A. Business Management, February 2003 *Summa cum Laude Hoseo University, Cheonan, South Korea Primary Area: Organizational Behavior RESEARCH INTERESTS Entrepreneurial Ecosystem; Strategic Leadership; Corporate Social Responsibility; Academic Technology Commercialization TEACHING INTERESTS Strategic Management; Principles of Management; Entrepreneurship; Business Ethics RESEARCH Journal Publications Hong-Ki Lee and Jihwan Hwang (2013), "A study on the effective use of Non-regular Workers: Focus on Small and Medium-size Manufacturing and Distribution Firms in Seoul- Incheon Area," Journal of Korean-Chinese Economics & Management, 12(1), 123-141 Hong-Ki Lee, Sung-Min Myoung, and Jihwan Hwang (2010), "A study on the effects of job satisfaction to organizational commitment and service-orientation," Journal of Korean- Chinese Economics & Management, 9(2), 163-181 Manuscripts under Review Dongwon Jung, Jihwan Hwang and Sam Hwang, “University Roles in Entrepreneurial Ecosystem” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal Jihwan Hwang