Henry Currey FRIBA (1820–1900): Leading Victorian Hospital Architect, and Early Exponent of the “Pavilion Principle” G C Cook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lambeth Transport Plan 2011

0 Contents 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 7 1.1 Background ................................................................................................. 7 1.2 How Lambeth’s Transport Plan has been developed.................................. 7 1.3 Structure of Lambeth’s Transport Plan (LTP).............................................. 9 2 Key Policy Influences .................................................................................... 11 2.1 National Policy........................................................................................... 11 2.1.1 Transport White Paper ...................................................................... 11 2.1.2 Traffic Management Act 2004 ........................................................... 11 2.2 London-wide policy.................................................................................... 12 2.2.1 Mayor’s Transport Strategy ............................................................... 12 2.3 Sub-regional policy.................................................................................... 15 2.4 Local Priorities........................................................................................... 16 2.4.1 Corporate Plan 2009-2012 ................................................................ 16 2.4.2 Our 2020 Vision - Lambeth's Sustainable Community Strategy........ 17 2.4.3 Local Area Agreement...................................................................... -

Manchester Group of the Victorian Society Newsletter Christmas 2020

MANCHESTER GROUP OF THE VICTORIAN SOCIETY NEWSLETTER CHRISTMAS 2020 WELCOME The views expressed within Welcome to the Christmas edition of the Newsletter. this publication are those of the authors concerned and Under normal circumstances we would be wishing all our members a Merry Christmas, not necessarily those of the but this Christmas promises to be like no other. We can do no more than express the wish Manchester Group of the that you all stay safe. Victorian Society. Our programme of events still remains on hold due to the Coronavirus pandemic and yet © Please note that articles further restrictions imposed in November 2020. We regret any inconvenience caused to published in this newsletter members but it is intended that events will resume when conditions allow. are copyright and may not be reproduced in any form without the consent of the author concerned. CONTENTS 2 PETER FLEETWOD HESKETH A LANCASHIRE ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIAN 4 FIELDEN PARK WEST DIDSBURY 8 MANCHESTER BREWERS AND THEIR MANSIONS: 10 REMINISCENCES OF PAT BLOOR 1937-2020 11 NEW BOOKS: ROBERT OWEN AND THE ARCHITECT JOSEPH HANSOM 11 FROM THE LOCAL PRESS 12 HERITAGE, CASH AND COVID-19 13 COMMITTEE MATTERS THE MANCHESTER GROUP OF THE VICTORIAN SOCIETY | 1 PETER FLEETWOOD-HESKETH, A LANCASHIRE ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIAN Richard Fletcher Charles Peter Fleetwood-Hesketh (1905-1985) is mainly remembered today for his book, Murray's Lancashire Architectural Guide, published by John Murray in 1955, and rivalling Pevsner's county guides in the Buildings of England series. Although trained as an architect, he built very little, and devoted his time to architectural journalism and acting as consultant to various organisations including the National Trust, the Georgian Group and the Thirties Society. -

Burtons St Leonards Newsletter Autumn 2019

James Burton Decimus Burton 1761-1837 Newsletter Autumn 2019 1800-1881 A GLORIOUS TRIP TO KEW Elizabeth Nathaniels We set off for Kew from St Leonards on a lovely spring day, Tuesday, 30 April. Joining us on the trip was Pat Thomas Allen, one of the authors of the attractive little booklet Travelling with Marianne North, describing the remarkable work of the daughter of a Hastings MP, who re- corded plants and scenery world-wide, and who is duly commemorated in Kew’s gallery named after her. Also with us was David Cruickshank, who plans to create a Marianne North trail in Jamaica, where there are historic links with Kew. During the trip on the coach, our Chairman, Christopher Maxwell-Stewart, and I said a few words about some of the treasures which awaited us. For him, these included a special exhi- bition of the large and intricate glass designs of Dale Chihuly dotted around the grounds, with their glistening brilliant colours and swirly shapes. For me, as ever, my prime interest lay in the work of Decimus Burton whose vast Temperate glass house (1863) (below) – the world’s largest Victorian glasshouse - had been recently restored under the immaculate care of Donald Insall &Associates. The drawing of the octagon may be seen in the archives at Kew. On arrival, free to do as we wished, David Cruickshank, Patrick Glass and I took the outra- geously touristic route by stepping aboard one of the rail-less ‘trains’ which circulate through- out the gardens, every half-hour, allowing passengers to stop off and get on again at will. -

Design & Access Statement for Listed Building Consent and Planning

TS Project Ref: 45177_H41_110329 NJA Project Ref: 0424 10 th August 2011 DESIGN & ACCESS STATEMENT FOR LISTED BUILDING CONSENT AND PLANNING APPLICATION FOR NEW ENTRANCE DOORS WITHIN THE LEFT HAND ARCHED RECESS OF THE CENTRE FIVE ARCHED RECESSES (INCLUDING CENTRAL ENTRANCE OPENING) TO THE NATURAL BATHS, THE CRESCENT, BUXTON SK17 6BQ Applicant: Buxton Crescent Hotel and Thermal Spa Company Ltd Agent: Stride Treglown, Architects Conservation Architect: Nicholas Jacob Architects Historic Significance The town of Buxton is the site of a thermal spring around which the Romans built a spa complex. Following the dark ages, the medieval period saw this spring being a place of cure by receiving the waters of St. Ann’s Well. This also saw the building of the Hall at Buxton and following a fire the new Hall. This is the place where Mary Queen of Scots was held under house arrest on the instructions of Queen Elizabeth of England. And it is here next to the Spa Bath as depicted by Speed on his map of Derbyshire that the Hall and subsequently the New Hall (now known as the Old Hall) is located. Following the destruction of the temple to the spring on the instructions of Oliver Cromwell, the spring fell into a period of little use. However, with the Georgian fashion of Spa visiting, Buxton had a new life, starting with John Barker’s new baths adjoining the Hall at Buxton which were constructed in 1712. Through the 18 th Century and early 19 th Century, a number of alterations were made to the baths culminating in a major re-design by Henry Currey between 1851 and 1856. -

'James and Decimus Burton's Regency New Town, 1827–37'

Elizabeth Nathaniels, ‘James and Decimus Burton’s Regency New Town, 1827–37’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XX, 2012, pp. 151–170 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2012 JAMES AND DECIMUS BURTON’S REGENCY NEW TOWN, ‒ ELIZABETH NATHANIELS During the th anniversary year of the birth of The land, which was part of the -acre Gensing James Burton ( – ) we can re-assess his work, Farm, was put up for sale by the trustees of the late not only as the leading master builder of late Georgian Charles Eversfield following the passing of a private and Regency London but also as the creator of an Act of Parliament which allowed them to grant entire new resort town on the Sussex coast, west of building leases. It included a favourite tourist site – Hastings. The focus of this article will be on Burton’s a valley with stream cutting through the cliff called role as planner of the remarkable townscape and Old Woman’s Tap. (Fig. ) At the bottom stood a landscape of St Leonards-on-Sea. How and why did large flat stone, locally named The Conqueror’s he build it and what role did his son, the acclaimed Table, said to have been where King William I had architect Decimus Burton, play in its creation? dined on the way to the Battle of Hastings. This valley was soon to become the central feature of the ames Burton, the great builder and developer of new town. The Conqueror’s table, however, was to Jlate Georgian London, is best known for his work be unceremoniously removed and replaced by James in the Bedford and Foundling estates, and for the Burton’s grand central St Leonards Hotel. -

Lambeth Bridge and the Location of the Southbound Bus Stop on Lambeth Palace Road Has Been Moved Back to Its Existing Location

Appendix B: Likely journey time impacts following changes to the design post consultation Summary of changes from 2017 consultation Following consultation feedback in 2017 several turning movements have now been retained eastbound onto Lambeth Bridge and the location of the southbound bus stop on Lambeth Palace Road has been moved back to its existing location. The following turning movements are now allowed at all times of day for all vehicles: Millbank North to Lambeth Bridge and Millbank South to Lambeth Bridge. The shared pedestrian and cycle areas have been reviewed and removed where it is safe for cyclists to use the carriageway. Shared use remains between Millbank South and Horseferry Road. There is also a carriageway level cycle lane through the footway between Millbank North and Lambeth Bridge. These alterations to the design in response to consultation feedback have resulted in some changes to the modelled journey times. Please note journey times are not directly comparable to the 2017 consultation. This is due to the modelled area being extended to ensure all journey times changes are captured by the modelling assessment. The tables below compare future modelled journey times with and without the Lambeth Bridge scheme. Both models include demand changes associated with committed developments and population growth, and planned changes to the road network. This allows us to isolate other changes on the network and present the predicted impact of the Lambeth Bridge scheme. 39 Revised Journey Times: Buses Future Journey Time without -

Albert Embankment Conservation Area Conservation Area Character

AlbertAlbert EmbankmentEmbankment Conservation Area Character Appraisal, 2017 Conservation Area Conservation Area Character Appraisal May 2017 Albert Embankment Conservation Area Character Appraisal, 2017 Lambeth river front in the 1750s. The construction of the Albert Embankment. 2 Albert Embankment Conservation Area Character Appraisal, 2017 CONTENTS PAGE CONSERVATION AREA CONTEXT MAP 4 CONSERVATION AREA MAP 5 INTRODUCTION 6 1. PLANNING FRAMEWORK 7 2. CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL 7 2.2 Geology 9 2.4 Historic Development 9 2.22 City Context 14 2.24 Spatial Analysis 15 2.75 Character Areas 29 2.103 Major Open Spaces 35 2.106 Trees 36 2.107 Building Materials and Details 36 2.111 Signs 37 2.112 Advertisements 37 2.113 Activities and Uses 37 2.114 Boundary Treatments 37 2.116 Public Realm 38 2.124 Public Art / Memorials 40 2.130 Designated Heritage Assets 42 2.133 Non Designated Heritage Assets 42 2.137 Positive Contributors 44 2.138 Views 44 2.151 Capacity for Change 48 2.152 Enhancement Opportunities 48 2.161 Appraisal Conclusion 50 APPENDICES 51 Appendix 1— WWHS Approaches map 51 Appendix 2— Statutory Listed Buildings 52 Appendix 3— Archaeological Priority Area No. 2 53 3 Albert Embankment Conservation Area Character Appraisal, 2017 CONSERVATION AREA CONTEXT MAP Whitehall CA CA 38 Westminster Abbey and CA 40 Parliament Square CA CA 10 Smith CA 50 Square CA Millbank CA CA 08 CA 56 Pimlico CA CA 32 08 – Kennington CA, 10 – Lambeth Palace CA, 32 – Vauxhall CA, 38 – South Bank CA, 40 – Lower Marsh CA, 50 – Lambeth Walk and China Walk CA, 56 – Vauxhall Gardens Estate CA. -

Venue Governors' Hall St Thomas' Hospital Westminster Bridge Road

Venue Governors’ Hall St Thomas’ Hospital Westminster Bridge Road London SE1 7EH Travelling to St Thomas’ (Governors Hall is located within St Thomas’ Hospital, South Wing, enter by the Main Entrance) Tube The nearest tube stations are: Westminster - District, Circle and Jubilee lines (10 minutes' walk) Waterloo - Bakerloo, Jubilee and Northern lines (15 minutes' walk) Lambeth North - Bakerloo line (15 minutes' walk) Train Waterloo and Waterloo East are the nearest railway stations, and a 10 - 15 minutes' walk away. Victoria and Charing Cross are 20 – 30 minutes' walk away. Bus Allow 15 - 20 minutes to get from the bus stop to where you need to be in the hospital. The following bus routes serve St Thomas': 12, 53, 148, 159, 211, 453, C10 - stop at Westminster Bridge Road 77, 507, N44 - stop at Lambeth Palace Road 3, 344, C10, N3 - stop at Lambeth Road (15 minutes' walk) 76, 341, 381, RV1 - stop at York Road Parking St Thomas' Hospital is located in the Congestion Charging zone. Please use public transport whenever possible. Parking for patients and visitors is very limited and there is often a queue The car park is 'pay on exit', which means you need to pay and get your exit ticket before returning to your car. If you pay by cash, please have the correct change. You can also pay by credit or debit card Parking charges: The car park is open 24 hours a day. Charges are: £3.00 per hour Charging exceptions: Disabled patients are given free parking in the main car park upon production of their blue badge registered in their name along with an appointment card. -

The Pavilion Keeper of the Mount

The Pavilion Keeper of The Mount For hundreds of years, right beneath your feet, tiny grains of sand have been gathering one by one to create a magnificent hill… The Mount! It is one of the most famous sand dunes in all of England. Celtic warriors, Roman soldiers and Viking raiders all probably stood and looked out across Morecambe Bay from the top of this sandy giant. Even one of the most famous queens of all time visited too, so you are literally standing in the footsteps of royalty! This sleepy sandy giant known back then as Starr Hill is about to become VERY famous; something VERY exciting is going to happen… Welcome to Georgian England, 200 years ago… ladies are not allowed to show their ankles, men are expected to grow giant face whiskers and it is considered very rude to look straight into the eyes of a stranger… unusual times! But more importantly a local landowner called Sir Peter Hesketh-Fleetwood (who had amazing face whiskers) is planning a brand new town. He wants to transform the sand dune, the mouth of the River Wyre and the land around them into a stylish new town with a port and a park and guess what… The Mount will be the magnificent centrepiece! The park around The Mount will have to be really fashionable, with exotic plants from around the world and hidden gardens. If you hunt carefully today you can still see and smell eucalyptus trees from Australia and purple lavender too; they both smell AMAZING! Georgian ‘Regency’ gardens are magical places with lots of surprises, beautiful colours and the best views. -

702231 MODERN ARCHITECTURE a Nash and the Regency

702231 MODERN ARCHITECTURE A Nash and the Regency the Regency 1811-1830 insanity of George III rule of the Prince Regent 1811-20 rule of George IV (former Prince Regent) 1820-1830 the Regency style lack of theoretical structure cavalier attitude to classical authority abstraction of masses and volumes shallow decoration and elegant colours exterior stucco and light ironwork decoration eclectic use of Greek Revival and Gothick elements Georgian house in Harley Street, London: interior view. MUAS10,521 PROTO-REGENCY CHARACTERISTICS abstract shapes shallow plaster decoration light colouration Osterley Park, Middlesex (1577) remodelled by 20 Portman Square, London, the Adam Brothers, 1761-80: the Etruscan Room. by Robert Adam, 1775-7: the music room MUAS 2,550 MUAS 2,238 ‘Etruscan’ decoration by the Adam brothers Syon House, Middlesex, remodelled by Robert Portland Place, London, Adam from 1762: door of the drawing room by the Adam brothers from 1773: detail MUAS 10,579 MUAS 24,511 shallow pilasters the Empire Style in France Bed for Mme M, and Armchair with Swan vases, both from Percier & Fontaine, Receuil de Décorations (1801) Regency drawing room, from Thomas Hope, Household Furniture and Decoration (1807) Regency vernacular with pilastration Sandford Park Hotel, Bath Road, Cheltenham Miles Lewis Regency vernacular with blind arches and Greek fret pilasters Oriel Place, Bath Road, Cheltenham photos Miles Lewis Regency vernacular with balconies No 24, The Front, Brighton; two views in Bayswater Road, London MUAS 8,397, 8,220, 8,222 'Verandah' [balcony], from J B Papworth, Rural Residences, Consisting of a Series of Designs for Cottages, Decorated Cottages, Small Villas, and other Ornamental Buildings .. -

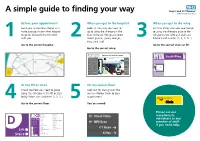

A Simple Guide to Finding Your Way

A simple guide to finding your way Before your appointment When you get to the hospital When you get to the wing Read your appointment letter and Look up the wing you need to Find the lift or stairs you need to go make sure you know what hospital go to using the directory in the to using the directory outside the to go to. Always bring the letter main entrance. Wings are colour- wing entrance. Lifts and stairs are 1 with you. 2 coded (purple, green, orange, 3 labelled with a letter (A, B, C, D…) blue, pink, red). Go to the correct hospital Go to the correct stairs or lift Go to the correct wing EastEast EastWing EastWing Wing Wing Guy’sGuy’s andGuy’s Stand Guy’sThomas’ and St Thomas’ Stand Thomas’ St Thomas’ NHS FoundationNHS FoundationNHS Trust FoundationNHS FoundationTrust Trust Trust East Wing Guy’s and St Thomas’ GassiotGassiotGassiotGassiot House House House House LambethLambethLambethLambeth Wing Wing Wing Wing NHS Foundation Trust Gassiot House Lambeth Wing NorthNorthNorth WingNorth Wing Wing Wing SouthSouthSouth WingSouth Wing Wing Wing North Wing South Wing South Wing ( Emergency( EmergencyDepartment( Emergency Department (A&E)( Emergency Department (A&E) Department (A&E) (A&E) ( Emergency Department (A&E) Outpatients Dental Services Blood Test Centre Dental Centre D Children’s Sleep Centre Children’s Dentistry Elizabeth Day Unit Orthodontics Eye Department Eye Emergency Kings College London South Wing Radiotherapy Twin Research £ £ £ £ Ground Floor Wards Adamson Centre (SLaM) Lane Fox Reception Facilities on the NetworkNetwork -

Domestic 3: Suburban and Country Houses Listing Selection Guide Summary

Domestic 3: Suburban and Country Houses Listing Selection Guide Summary Historic England’s twenty listing selection guides help to define which historic buildings are likely to meet the relevant tests for national designation and be included on the National Heritage List for England. Listing has been in place since 1947 and operates under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. If a building is felt to meet the necessary standards, it is added to the List. This decision is taken by the Government’s Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). These selection guides were originally produced by English Heritage in 2011: slightly revised versions are now being published by its successor body, Historic England. The DCMS‘ Principles of Selection for Listing Buildings set out the over-arching criteria of special architectural or historic interest required for listing and the guides provide more detail of relevant considerations for determining such interest for particular building types. See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/principles-of- selection-for-listing-buildings. Each guide falls into two halves. The first defines the types of structures included in it, before going on to give a brisk overview of their characteristics and how these developed through time, with notice of the main architects and representative examples of buildings. The second half of the guide sets out the particular tests in terms of its architectural or historic interest a building has to meet if it is to be listed. A select bibliography gives suggestions for further reading. This guide, one of four on different types of Domestic Buildings, covers suburban and country houses.