Lambeth Palace Conservation Area Character Appraisal 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lambeth Methodist Mission, 3-5 Lambeth Road

ADDRESS: Lambeth Methodist Mission, 3 - 5 Lambeth Road London SE1 7DQ Application Number: 18/03890/FUL Case Officer: Rozina Vrlic Ward: Bishops Date Received: 31.08.2018 Proposal: Demolition of the existing building and redevelopment of the site to erect a Part 1/4/12 Storey (plus basement) building for the Lambeth Methodist Mission (Class D1) with ancillary café, two residential dwellings (Class C3) and hotel (Class C1) (137 beds) with ancillary bar and restaurant, with associated cycle parking and hard and soft landscaping. Applicant: Lambeth Developments Ltd Agent: DP9 Planning Consultants RECOMMENDATION 1. Resolve to refuse planning permission for the reasons set in appendix 1 of the officer report. 2. If there is a subsequent appeal, delegated authority is given to the Assistant Director of Planning, Transport and Development, having regard to the heads of terms set out in this report, addendums and/or PAC minutes, to negotiate and complete a document containing obligations pursuant to Section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended) in order to meet the requirement of the Planning Inspector. In the event that Committee resolve to grant conditional planning permission subject to the completion of an agreement under Section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended) containing the planning obligations listed in this report and any direction as may be received following further referral to the Mayor of London.Agree to delegate authority to the Assistant Director of Planning, Transport and Development to: a. Finalise the recommended conditions as set out in this report, addendums and/or PAC minutes; and b. -

Spotlight on Oval Content

SPOTLIGHT ON OVAL CONTENT HISTORY AND HERITAGE PAGE 2-8 TRANSPORT PAGE 9-14 Set between the neighbourhoods of Vauxhall and Kennington, Oval is a community with tree-lined EDUCATION streets and tranquil parks. A place to meet friends, PAGE 15-21 family or neighbours across its lively mosaic of new bars, cafés, shops and art galleries. A place that FOOD AND DRINK feels local but full of life, relaxed but rearing to go. PAGE 22-29 It is a place of warmth and energy, adventure and opportunity. Just a ten-minute walk from Vauxhall, CULTURE Oval and Kennington stations, Oval Village has a PAGE 30-39 lifestyle of proximity, flexibility and connectivity. PAGE 1 HISTORY AND HERITAGE A RICH HISTORY AND HERITAGE No. 1 THE KIA OVAL The Kia Oval has been the home ground of the Surrey County cricket club since 1845. It was the first ground in England to host international test cricket and in recent years has seen significant redevelopment and improved capacity. No. 2 LAMBETH PALACE For nearly 800 years, Lambeth Palace, on the banks of the river Thames, has been home to the Archbishop of Canterbury. The beautiful grounds host a series of fetes and open days whilst guided tours can be booked in order to explore the rooms and chapels of this historic working palace and home. PAGE 4 PAGE 5 No. 3 HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT The Palace of Westminster, more commonly known as the Houses of Parliament, has resided in the centre of London since the 11th Century. Formerly a royal residence it has, over the centuries, become a centre of political life. -

Lambeth Transport Plan 2011

0 Contents 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 7 1.1 Background ................................................................................................. 7 1.2 How Lambeth’s Transport Plan has been developed.................................. 7 1.3 Structure of Lambeth’s Transport Plan (LTP).............................................. 9 2 Key Policy Influences .................................................................................... 11 2.1 National Policy........................................................................................... 11 2.1.1 Transport White Paper ...................................................................... 11 2.1.2 Traffic Management Act 2004 ........................................................... 11 2.2 London-wide policy.................................................................................... 12 2.2.1 Mayor’s Transport Strategy ............................................................... 12 2.3 Sub-regional policy.................................................................................... 15 2.4 Local Priorities........................................................................................... 16 2.4.1 Corporate Plan 2009-2012 ................................................................ 16 2.4.2 Our 2020 Vision - Lambeth's Sustainable Community Strategy........ 17 2.4.3 Local Area Agreement...................................................................... -

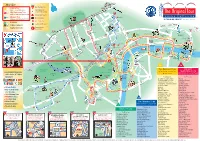

A4 Web Map 26-1-12:Layout 1

King’s Cross Start St Pancras MAP KEY Eurostar Main Starting Point Euston Original Tour 1 St Pancras T1 English commentary/live guides Interchange Point City Sightseeing Tour (colour denotes route) Start T2 W o Language commentaries plus Kids Club REGENT’S PARK Euston Rd b 3 u Underground Station r n P Madame Tussauds l Museum Tour Russell Sq TM T4 Main Line Station Gower St Language commentaries plus Kids Club q l S “A TOUR DE FORCE!” The Times, London To t el ★ River Cruise Piers ss Gt Portland St tenham Ct Rd Ru Baker St T3 Loop Line Gt Portland St B S s e o Liverpool St Location of Attraction Marylebone Rd P re M d u ark C o fo t Telecom n r h Stansted Station Connector t d a T5 Portla a m Museum Tower g P Express u l p of London e to S Aldgate East Original London t n e nd Pl t Capital Connector R London Wall ga T6 t o Holborn s Visitor Centre S w p i o Aldgate Marylebone High St British h Ho t l is und S Museum el Bank of sdi igh s B tch H Gloucester Pl s England te Baker St u ga Marylebone Broadcasting House R St Holborn ld d t ford A R a Ox e re New K n i Royal Courts St Paul’s Cathedral n o G g of Justice b Mansion House Swiss RE Tower s e w l Tottenham (The Gherkin) y a Court Rd M r y a Lud gat i St St e H n M d t ill r e o xfo Fle Fenchurch St Monument r ld O i C e O C an n s Jam h on St Tower Hill t h Blackfriars S a r d es St i e Oxford Circus n Aldwyc Temple l a s Edgware Rd Tower Hil g r n Reg Paddington P d ve s St The Monument me G A ha per T y Covent Garden Start x St ent Up r e d t r Hamleys u C en s fo N km Norfolk -

Lambeth Bridge and the Location of the Southbound Bus Stop on Lambeth Palace Road Has Been Moved Back to Its Existing Location

Appendix B: Likely journey time impacts following changes to the design post consultation Summary of changes from 2017 consultation Following consultation feedback in 2017 several turning movements have now been retained eastbound onto Lambeth Bridge and the location of the southbound bus stop on Lambeth Palace Road has been moved back to its existing location. The following turning movements are now allowed at all times of day for all vehicles: Millbank North to Lambeth Bridge and Millbank South to Lambeth Bridge. The shared pedestrian and cycle areas have been reviewed and removed where it is safe for cyclists to use the carriageway. Shared use remains between Millbank South and Horseferry Road. There is also a carriageway level cycle lane through the footway between Millbank North and Lambeth Bridge. These alterations to the design in response to consultation feedback have resulted in some changes to the modelled journey times. Please note journey times are not directly comparable to the 2017 consultation. This is due to the modelled area being extended to ensure all journey times changes are captured by the modelling assessment. The tables below compare future modelled journey times with and without the Lambeth Bridge scheme. Both models include demand changes associated with committed developments and population growth, and planned changes to the road network. This allows us to isolate other changes on the network and present the predicted impact of the Lambeth Bridge scheme. 39 Revised Journey Times: Buses Future Journey Time without -

“London Day.” Dear Brothers and Sisters

London Day. That’s what it was called, “London Day.” Dear Brothers and Sisters: It was London Day, in all that one might imagine. We woke early to get a quick breakfast, and then got in a queue (a line). This is nothing unusual about getting in a queue. In fact, I think there are queues to prepare to get into another queue. It seems to be a way of life. This queue was to get on the coaches that would be taking us on the two hour trip to London. The ride in was uneventful, filled with sleeping bishops and spouses, and those talking about various aspects of life. When we arrived in London, it was just as one might imagine it: the Parliament Buildings, Westminster Abbey, ‘Big Ben’ and all the rest. We actually arrived early, and so I thought we might have a few minutes to wander around. Wrong! It was off the bus…and into another queue. We walked to Whitehall Place and waited. As more and more bishops gathered -- Nigerians, Sudanese, American, and all the rest -- we noticed that security was quite visibly present. Soon a helicopter was hovering overhead, just to make sure that nothing happened. Around 10:00 people came around to pass out placards and special “Social Justice Bibles.” Many of us took one or both and prepared to carry them along the route. We began our Walk of Witness. The march took us past Downing Street, ‘Big Ben,’ the Houses of Parliament and Westminster Abbey. We ended the walk at Lambeth Palace – the London home of the Archbishop of Canterbury. -

Westminster World Heritage Site Management Plan Steering Group

WESTMINSTER WORLD HERITAGE SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN Illustration credits and copyright references for photographs, maps and other illustrations are under negotiation with the following organisations: Dean and Chapter of Westminster Westminster School Parliamentary Estates Directorate Westminster City Council English Heritage Greater London Authority Simmons Aerofilms / Atkins Atkins / PLB / Barry Stow 2 WESTMINSTER WORLD HERITAGE SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN The Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including St. Margaret’s Church World Heritage Site Management Plan Prepared on behalf of the Westminster World Heritage Site Management Plan Steering Group, by a consortium led by Atkins, with Barry Stow, conservation architect, and tourism specialists PLB Consulting Ltd. The full steering group chaired by English Heritage comprises representatives of: ICOMOS UK DCMS The Government Office for London The Dean and Chapter of Westminster The Parliamentary Estates Directorate Transport for London The Greater London Authority Westminster School Westminster City Council The London Borough of Lambeth The Royal Parks Agency The Church Commissioners Visit London 3 4 WESTMINSTER WORLD HERITAGE S I T E M ANAGEMENT PLAN FOREWORD by David Lammy MP, Minister for Culture I am delighted to present this Management Plan for the Palace of Westminster, Westminster Abbey and St Margaret’s Church World Heritage Site. For over a thousand years, Westminster has held a unique architectural, historic and symbolic significance where the history of church, monarchy, state and law are inexorably intertwined. As a group, the iconic buildings that form part of the World Heritage Site represent masterpieces of monumental architecture from medieval times on and which draw on the best of historic construction techniques and traditional craftsmanship. -

London Globally Considered the Best Theatre Scene in the World, London, England Theatre Trips Offer Educational Opportunities for Your Students

TOP T HEATRE DESTINATIONS: London Globally considered the best theatre scene in the world, London, England theatre trips offer educational opportunities for your students. Educational Destinations offers a variety of London, England theatre trip opportunities that allows your students to see what is was like to put on a Shakespearean play like in the late-1500’s, visit the magestic Romanesque or Victorian theatres, learn from professional performers, or even participate in a Shakespeare workshop, Educational Destinations can make your London, England theatre trip rewarding and memorable. EDUCATIONAL T HEATRE OPPORTUNITIES: • Stage Scenes from Your Favourite • The Business of Theatre • Creating Original Performances Play • Producing Theatre Workshops • West End Parties • Working Freelance • Acting workshop - Playing Age • Musical Theatre Company • Bespoke Coaching • A Playwright’s Toolkit: Writing for • Introduction to Musical Theatre • Accent Clinic Theatre • Lip Sync Battles • Audition Workshops • Young Technicians • Contemporary Dance • Acting for Improvers • Devising: Making collaborative • Jazz Dance Company • Beginners Commercial Street theatre with Rhum and Clay • Diva Dance Company Dance • Staging Naturalism • Physical Theatre Course • Shakespeare Classes • Theatre Design and • Anatomy of an Immersive | Dance • Screen Acting for Beginners Environmental Impact | Theatre Scene • Musical Theatre Beginners • Cast Discussions • Improvised Theatre Courses • Acting for Intermediates • Theatre Tours • Theatre Design, Crafts and • City Singers -

Albert Embankment Conservation Area Conservation Area Character

AlbertAlbert EmbankmentEmbankment Conservation Area Character Appraisal, 2017 Conservation Area Conservation Area Character Appraisal May 2017 Albert Embankment Conservation Area Character Appraisal, 2017 Lambeth river front in the 1750s. The construction of the Albert Embankment. 2 Albert Embankment Conservation Area Character Appraisal, 2017 CONTENTS PAGE CONSERVATION AREA CONTEXT MAP 4 CONSERVATION AREA MAP 5 INTRODUCTION 6 1. PLANNING FRAMEWORK 7 2. CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL 7 2.2 Geology 9 2.4 Historic Development 9 2.22 City Context 14 2.24 Spatial Analysis 15 2.75 Character Areas 29 2.103 Major Open Spaces 35 2.106 Trees 36 2.107 Building Materials and Details 36 2.111 Signs 37 2.112 Advertisements 37 2.113 Activities and Uses 37 2.114 Boundary Treatments 37 2.116 Public Realm 38 2.124 Public Art / Memorials 40 2.130 Designated Heritage Assets 42 2.133 Non Designated Heritage Assets 42 2.137 Positive Contributors 44 2.138 Views 44 2.151 Capacity for Change 48 2.152 Enhancement Opportunities 48 2.161 Appraisal Conclusion 50 APPENDICES 51 Appendix 1— WWHS Approaches map 51 Appendix 2— Statutory Listed Buildings 52 Appendix 3— Archaeological Priority Area No. 2 53 3 Albert Embankment Conservation Area Character Appraisal, 2017 CONSERVATION AREA CONTEXT MAP Whitehall CA CA 38 Westminster Abbey and CA 40 Parliament Square CA CA 10 Smith CA 50 Square CA Millbank CA CA 08 CA 56 Pimlico CA CA 32 08 – Kennington CA, 10 – Lambeth Palace CA, 32 – Vauxhall CA, 38 – South Bank CA, 40 – Lower Marsh CA, 50 – Lambeth Walk and China Walk CA, 56 – Vauxhall Gardens Estate CA. -

Venue Governors' Hall St Thomas' Hospital Westminster Bridge Road

Venue Governors’ Hall St Thomas’ Hospital Westminster Bridge Road London SE1 7EH Travelling to St Thomas’ (Governors Hall is located within St Thomas’ Hospital, South Wing, enter by the Main Entrance) Tube The nearest tube stations are: Westminster - District, Circle and Jubilee lines (10 minutes' walk) Waterloo - Bakerloo, Jubilee and Northern lines (15 minutes' walk) Lambeth North - Bakerloo line (15 minutes' walk) Train Waterloo and Waterloo East are the nearest railway stations, and a 10 - 15 minutes' walk away. Victoria and Charing Cross are 20 – 30 minutes' walk away. Bus Allow 15 - 20 minutes to get from the bus stop to where you need to be in the hospital. The following bus routes serve St Thomas': 12, 53, 148, 159, 211, 453, C10 - stop at Westminster Bridge Road 77, 507, N44 - stop at Lambeth Palace Road 3, 344, C10, N3 - stop at Lambeth Road (15 minutes' walk) 76, 341, 381, RV1 - stop at York Road Parking St Thomas' Hospital is located in the Congestion Charging zone. Please use public transport whenever possible. Parking for patients and visitors is very limited and there is often a queue The car park is 'pay on exit', which means you need to pay and get your exit ticket before returning to your car. If you pay by cash, please have the correct change. You can also pay by credit or debit card Parking charges: The car park is open 24 hours a day. Charges are: £3.00 per hour Charging exceptions: Disabled patients are given free parking in the main car park upon production of their blue badge registered in their name along with an appointment card. -

Freehold Building in a Prime South London Location St Mary's Rectory

Freehold building in a prime South London location St Mary’s Rectory, Lambeth Road, SE1 7JY For Sale g A Grade II listed building used as a postgraduate hall of residence situated adjacent to Archbishop’s Park and in close proximity to Westminster and the South Bank. g The property extends to approximately 613 sq m (6,598 sq ft) GIA set over three storeys on a plot of approximately 0.34 acres. g Potential for refurbishment or alternative uses including residential subject to the necessary consents g For sale freehold with vacant possession 33 Margaret Street London W1G 0JD savills.co.uk Arrow indicates approximate location for identification purposes only Location The property is located on Lambeth Road in South London in the London Borough of Lambeth. The Houses of Parliament are located approximately 600m to the north west via Lambeth Bridge and the leisure and cultural offer at the South Bank is 1km to the north. Lambeth North Underground Station, providing Bakerloo line services is located approximately 600 metres to the north east and Waterloo Station is 1km to the north. Regular bus services into central London run along Lambeth Road. Description St Mary’s Rectory is a Grade II listed building constructed in the 19th Century. The building is set over three storeys with a late 19th Century extension to the front. It occupies a plot extending to approximately 0.34 acres which is bounded by a brick wall. To the front of the property is a gravelled area and a standalone garage and to the rear a garden comprising a lawned area and flower beds. -

= Grammatical Edits and Suggestions

Lambeth Palace Conservation Area DRAFT Conservation Area Statement October 2013 Draft Lambeth Palace Conservation Area Statement, October 2013 CURRENT CONSERVATION AREA CONTEXT 38 40 CA 08 Kennington CA 40 Lower Marsh CA 09 Walcot Square CA 50 Lambeth Walk / China Walk CA 10 Lambeth Palace CA 57 Vauxhall Gardens Estate CA 38 South Bank CA 57 Albert Embankment Draft Lambeth Palace Conservation Area Statement, October 2013 CURRENT CONSERVATION AREA BOUNDARY Draft Lambeth Palace Conservation Area Statement, October 2013 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Lambeth Palace Conservation Area was designated in 1968 and originally consisted of only Lambeth Palace and its grounds. The boundary was subsequently extended several times: in 1978 Archbishop’s Park and the surrounding historic buildings along Lambeth Road were added, and in 1980 the historic part of St. Thomas’s Hospital and Albert Embankment were included. 1.2 The conservation area is in the northern part of Lambeth. It is bounded to the west by the River Thames. It encompasses the surviving Victorian buildings of St Thomas’ Hospital and is bounded to the north by Royal Street. To the east Carlisle Lane and the railway viaduct forms the boundary, which then runs along Lambeth Road. 1.3 This area is exceptionally important to London - Lambeth Palace being a complex of great significance both architecturally and historically; it contains elements dating from the early 12th century and has a strong constitutional and physical relationship with the Palace of Westminster. Its presence has significantly influenced the development of the area over the centuries and many local buildings and projects have carried a connection with the Palace or former Archbishops of Canterbury.