Waterloo Guided Walks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Adjacent to 16 Beardell Street, Crystal Palace, London SE19 1TP Freehold Development Site with Planning Permission for 5 Apartments View More Information

CGI of proposed Land adjacent to 16 Beardell Street, Crystal Palace, London SE19 1TP Freehold development site with planning permission for 5 apartments View more information... Land adjacent to 16 Beardell Street, Crystal Palace, London SE19 1TP Home Description Location Planning Terms View all of our instructions here... III III • Vacant freehold plot • Sold with planning permission for 5 apartments • Contemporary 3 storey block • Well-located close by to Crystal Palace ‘triangle’ and Railway Station • OIEO £950,000 F/H DESCRIPTION An opportunity to acquire a freehold development site sold with planning permission for the erection for a 3 storey block comprising 5 apartments (2 x studio, 2 x 2 bed & 1 x 3 bed). LOCATION Positioned on Beardell Street the property is located in the heart of affluent Crystal Palace town centre directly adjacent to the popular Crystal Palace ‘triangle’ which offers an array of independent shops, restaurants and bars mixed in with typical high street amenities. In terms of transport, the property is located 0.5 miles away from Crystal Palace Station which provides commuters with National Rail services to London Bridge, London Victoria, West Croydon, and Beckenham Junction and London Overground services between Highbury and Islington (via New Cross) and Whitechapel. E: [email protected] W: acorncommercial.co.uk 120 Bermondsey Street, 1 Sherman Road, London SE1 3TX Bromley, Kent BR1 3JH T: 020 7089 6555 T: 020 8315 5454 Land adjacent to 16 Beardell Street, Crystal Palace, London SE19 1TP Home Description Location Planning Terms View all of our instructions here... III III PLANNING The property has been granted planning permission by Lambeth Council (subject to S106 agreement which has now been agreed) for the ‘Erection of 3 storey building plus basement including a front lightwell to provide 5 residential units, together with provision of cycle stores, refuse/recycling storages and private gardens.’ Under ref: 18/00001/FUL. -

Waterloo Building Height Study, 2018

Waterloo Building Height Study, 2018 1. Introduction 1.1 This study has been undertaken to inform Lambeth’s approach to tall buildings in Waterloo as part of the Lambeth Local Plan Review, 2018. 2. Background The Waterloo Opportunity Area 2.1 The London Plan identifies Waterloo as an Opportunity Area and the objectives are outlined in the Mayor’s Waterloo Opportunity Area Planning Framework (2007) which include: ‘Development potential in the area should be maximised given Waterloo’s status as an opportunity Area and its location within the Central Activities Zone and to accord with the strategy of providing the highest levels of activity at locations with the greatest transport capacity’. 2.2 The OAPF identified two broad areas suitable for tall building – above and around the station and on the commercial spine behind the Riverside (Belvedere Road and Upper Ground) – based in part on the presence of tall buildings in these locations already. The associated illustrations generally show a cluster of tall buildings over Waterloo Station which would be delivered as part of a station redevelopment which would push the passenger concourse to ground level allowing the platforms to be extended. 2.3 The OAPF recognises the need for development to respond to this sensitive context: ‘Additionally, development potential has to be tempered against the normal impacts of development assessed by the planning system including the impact on character areas and on local and strategic views’. (OAPF page 99). 2.4 Figure 49 identifies five areas of possible development within and around the railway station: 1. Elizabeth House and surrounds, 2. -

Planning Weekly List & Decisions

Planning Weekly List & Decisions Appeals (Received/Determined) and Planning Applications & Notifications (Validated/Determined) Week Ending 09/10/2020 The attached list contains Planning and related applications being considered by the Council, acting as the Local Planning Authority. Details have been entered on the Statutory Register of Applications. Online application details and associated documents can be viewed via Public Access from the Lambeth Planning Internet site, https://www.lambeth.gov.uk/planning-and-building- control/planning-applications/search-planning-applications. A facility is also provided to comment on applications pending consideration. We recommend that you submit comments online. You will be automatically provided with a receipt for your correspondence, be able to track and monitor the progress of each application and, check the 21 day consultation deadline. Under the Local Government (Access to Information) Act 1985, any comments made are open to inspection by the public and in the event of an Appeal will be referred to the Planning Inspectorate. Confidential comments cannot be taken into account in determining an application. Application Descriptions The letters at the end of each reference indicate the type of application being considered. ADV = Advertisement Application P3J = Prior Approval Retail/Betting/Payday Loan to C3 CON = Conservation Area Consent P3N = Prior Approval Specified Sui Generis uses to C3 CLLB = Certificate of Lawfulness Listed Building P3O = Prior Approval Office to Residential DET = Approval -

Lambeth College

Further Education Commissioner assessment summary Lambeth College October 2016 Contents Assessment 3 Background 3 Assessment Methodology 4 The Role, Composition and Operation of the Board 4 The Clerk to the Corporation 4 The Executive Team 5 The Qualify of Provision 5 Student Numbers 5 The College's Financial Position 6 Financial Forecasts beyond 2015/2016 6 Capital Developments 6 Financial Oversight by the Board 6 Budget-setting Arrangements 7 Financial Reporting 7 Audit 7 Conclusions 7 Recommendations 8 2 Assessment Background The London Borough of Lambeth is the second largest inner London Borough with a population of 322,000 (2015 estimate). It has experienced rapid population growth, increasing by over 50,000 in the last 10 years up until 2015. There are five key town centers: Brixton, Clapham and Stockwell, North Lambeth (Waterloo, Vauxhall, Kennington), and Norwood and Streatham. Lambeth is the 5th most deprived Borough in London. One in five of the borough’s residents work in jobs that pay below the London Living Wage. This is reflected by the fact that nearly one in four (24%) young people live in families who receive tax credits. Major regeneration developments and improvements are underway for Waterloo and Vauxhall and the Nine Elms Regeneration project which will drive the transformation of these areas. Lambeth College has three main campuses in the borough, based in Clapham, Brixton and Vauxhall. Approximately a quarter of the student cohort in any given academic year are 16‐18 learners. In addition to this, there is also a significantly growing proportion of 16-18 learners on Apprenticeship programmes, moderate numbers on workplace‐training provision for employers and school link programmes which are offered to relatively smaller learner volumes. -

SOUTH BANK GUIDE One Blackfriars

SOUTH BANK GUIDE One Blackfriars The South Bank has seen a revolution over the past 04/ THE HEART OF decade, culturally, artistically and architecturally. THE SOUTH BANK Pop up restaurants, food markets, festivals, art 08/ installations and music events have transformed UNIQUE the area, and its reputation as one of London’s LIFESTYLE most popular destinations is now unshakeable. 22/ CULTURAL Some of the capital’s most desirable restaurants and LANDSCAPE bars are found here, such as Hixter, Sea Containers 34/ and the diverse offering of The Shard. Culture has FRESH always had a place here, ever since the establishment PERSPECTIVES of the Festival Hall in 1951. Since then, it has been 44/ NEW joined by global champions of arts and theatre such HORIZONS as the Tate Modern, the National Theatre and the BFI. Arts and culture continues to flourish, and global businesses flock to establish themselves amongst such inspiring neighbours. Influential Blue Chips, global professional and financial services giants and major international media brands have chosen to call this unique business hub home. With world-class cultural and lifestyle opportunities available, the South Bank is also seeing the dawn of some stunning new residential developments. These ground-breaking schemes such as One Blackfriars bring an entirely new level of living to one of the world’s most desirable locations. COMPUTER ENHANCED IMAGE OF ONE BLACKFRIARS IS INDICATIVE ONLY 1 THE HEART OF THE SOUTH BANK THE SHARD CANARY WHARF 30 ST MARY AXE STREET ONE BLACKFRIARS TOWER BRIDGE -

Trader Terms and Conditions 2019 - 2020

Trader Terms and conditions 2019 - 2020 1 Contents Trader information ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Requirements to trade ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Compliance Documents ................................................................................................................................ 4 Regulations and Conditions .............................................................................................................................. 5 Opening hours ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Deposit and Payments .................................................................................................................................. 6 Pitch & Canopy .............................................................................................................................................. 6 Fees ............................................................................................................................................................... 7 Customer payment method ......................................................................................................................... 7 Policy for augmenting menus ...................................................................................................................... -

Cashbox Subscription: Please Check Classification;

July 13, 1985 NEWSPAPER $3.00 v.'r '-I -.-^1 ;3i:v l‘••: • •'i *. •- i-s .{' *. » NE RIAA CERTIFICATIONS ANNOUNCED R.E.M. AFFILIATES LIVE-AID Crass Roots Audience Blossoms TWORK, GEAR FOR Story on Page 13 WEHIND THE BULLETS: TEARS FOR FEARS #1 MTV AWARDS ENTER NEXT PHASE GUEST EDITORIAL: AL KOOPER SUBSCRIPTION ORDER: PLEASE ENTER MY CASHBOX SUBSCRIPTION: PLEASE CHECK CLASSIFICATION; RETAILER ARTIST I NAME VIDEO JUKEBOXES DEALER AMUSEMENT GAMES COMPANY TITLE ONE-STOP VENDING MACHINES DISTRIBUTOR RADIO SYNDICATOR ADDRESS BUSINESS HOME APT. NO. RACK JOBBER RADIO CONSULTANT PUBLISHER INDEPENDENT PROMOTION CITY STATE/PROVINCE/COUNTRY ZIP RECORD COMPANY INDEPENDENT MARKETING RADIO OTHER: NATURE OF BUSINESS PAYMENT ENCLOSED SIGNATURE DATE USA OUTSIDE USA FOR 1 YEAR I YEAR (52 ISSUES) $125.00 AIRMAIL $195.00 6 MONTHS (26 ISSUES) S75.00 1 YEAR FIRST CLASS/AIRMAIL SI 80.00 01SHBCK (Including Canada & Mexico) 330 WEST 58TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10019 ' 01SH BOX HE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC / COIN MACHINE / HOME ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY VOLUME XLIX — NUMBER 5 — July 13, 1985 C4SHBO( Guest Editorial : T Taking Care Of Our Own ^ GEORGE ALBERT i. President and Publisher By A I Kooper MARK ALBERT 1 The recent and upcoming gargantuan Ethiopian benefits once In a very true sense. Bob Geldof has helped reawaken our social Vice President and General Manager “ again raise an issue that has troubled me for as long as I’ve been conscience; now we must use it to address problems much closer i SPENCE BERLAND a part of this industry. We, in the American music business do to home. -

Lambeth Methodist Mission, 3-5 Lambeth Road

ADDRESS: Lambeth Methodist Mission, 3 - 5 Lambeth Road London SE1 7DQ Application Number: 18/03890/FUL Case Officer: Rozina Vrlic Ward: Bishops Date Received: 31.08.2018 Proposal: Demolition of the existing building and redevelopment of the site to erect a Part 1/4/12 Storey (plus basement) building for the Lambeth Methodist Mission (Class D1) with ancillary café, two residential dwellings (Class C3) and hotel (Class C1) (137 beds) with ancillary bar and restaurant, with associated cycle parking and hard and soft landscaping. Applicant: Lambeth Developments Ltd Agent: DP9 Planning Consultants RECOMMENDATION 1. Resolve to refuse planning permission for the reasons set in appendix 1 of the officer report. 2. If there is a subsequent appeal, delegated authority is given to the Assistant Director of Planning, Transport and Development, having regard to the heads of terms set out in this report, addendums and/or PAC minutes, to negotiate and complete a document containing obligations pursuant to Section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended) in order to meet the requirement of the Planning Inspector. In the event that Committee resolve to grant conditional planning permission subject to the completion of an agreement under Section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended) containing the planning obligations listed in this report and any direction as may be received following further referral to the Mayor of London.Agree to delegate authority to the Assistant Director of Planning, Transport and Development to: a. Finalise the recommended conditions as set out in this report, addendums and/or PAC minutes; and b. -

Spotlight on Oval Content

SPOTLIGHT ON OVAL CONTENT HISTORY AND HERITAGE PAGE 2-8 TRANSPORT PAGE 9-14 Set between the neighbourhoods of Vauxhall and Kennington, Oval is a community with tree-lined EDUCATION streets and tranquil parks. A place to meet friends, PAGE 15-21 family or neighbours across its lively mosaic of new bars, cafés, shops and art galleries. A place that FOOD AND DRINK feels local but full of life, relaxed but rearing to go. PAGE 22-29 It is a place of warmth and energy, adventure and opportunity. Just a ten-minute walk from Vauxhall, CULTURE Oval and Kennington stations, Oval Village has a PAGE 30-39 lifestyle of proximity, flexibility and connectivity. PAGE 1 HISTORY AND HERITAGE A RICH HISTORY AND HERITAGE No. 1 THE KIA OVAL The Kia Oval has been the home ground of the Surrey County cricket club since 1845. It was the first ground in England to host international test cricket and in recent years has seen significant redevelopment and improved capacity. No. 2 LAMBETH PALACE For nearly 800 years, Lambeth Palace, on the banks of the river Thames, has been home to the Archbishop of Canterbury. The beautiful grounds host a series of fetes and open days whilst guided tours can be booked in order to explore the rooms and chapels of this historic working palace and home. PAGE 4 PAGE 5 No. 3 HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT The Palace of Westminster, more commonly known as the Houses of Parliament, has resided in the centre of London since the 11th Century. Formerly a royal residence it has, over the centuries, become a centre of political life. -

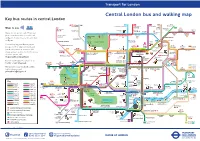

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

London Borough of Lambeth

LONDON BOROUGH OF LAMBETH LAMBETH ARCHIVES DEPARTMENT Reference number IV/224 Title Morley College Covering dates 1888-2013 Physical extent 29 boxes & 2 volumes Creator Morley College Administrative history Morley College originated in the work of the Coffee Music Halls Company Ltd. who promoted temperance and the arts in London. The college was established by Emma Cons, a visionary and social reformer who fought to improve standards of London’s Waterloo district. In 1880, Cons, with the support of the Coffee Music Halls Company Ltd. leased what is now known as the ‘Old Vic’ theatre and created the Royal Victoria Coffee and Music Hall. In 1882 the hall began to host weekly lectures in which eminent scientists would address the public on a wide range of topics. The success of these lectures led to the establishment of Morley Memorial College for working men and women, named after Samuel Morley, a textile manufacturer, MP and philanthropist who contributed to Morley College. In the 1920s the college moved to Westminster Bridge Road where it remains today although it has since expanded and now includes Morley Gallery and Arts Studio and the Nancy Seear Building. The college has attracted eminent staff including composer Gustav Holst, Director of Music 1907- 1924, a post later filled by Sir Michael Kemp Tippet, 1940-1951. Other high profile personalities associated with the college include composer Ralph Vaughn Williams, writer Virginia Woolf and artist David Hockney. Acquisition or transfer information Collection acquired by Lambeth Archives between 1999-2007 as a gift. Acquisition numbers: 1999/11, 2002/30, 2003/13, 2006/11, 2007/23; ARC/2013/6,8. -

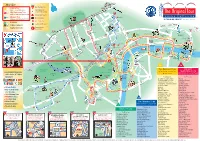

A4 Web Map 26-1-12:Layout 1

King’s Cross Start St Pancras MAP KEY Eurostar Main Starting Point Euston Original Tour 1 St Pancras T1 English commentary/live guides Interchange Point City Sightseeing Tour (colour denotes route) Start T2 W o Language commentaries plus Kids Club REGENT’S PARK Euston Rd b 3 u Underground Station r n P Madame Tussauds l Museum Tour Russell Sq TM T4 Main Line Station Gower St Language commentaries plus Kids Club q l S “A TOUR DE FORCE!” The Times, London To t el ★ River Cruise Piers ss Gt Portland St tenham Ct Rd Ru Baker St T3 Loop Line Gt Portland St B S s e o Liverpool St Location of Attraction Marylebone Rd P re M d u ark C o fo t Telecom n r h Stansted Station Connector t d a T5 Portla a m Museum Tower g P Express u l p of London e to S Aldgate East Original London t n e nd Pl t Capital Connector R London Wall ga T6 t o Holborn s Visitor Centre S w p i o Aldgate Marylebone High St British h Ho t l is und S Museum el Bank of sdi igh s B tch H Gloucester Pl s England te Baker St u ga Marylebone Broadcasting House R St Holborn ld d t ford A R a Ox e re New K n i Royal Courts St Paul’s Cathedral n o G g of Justice b Mansion House Swiss RE Tower s e w l Tottenham (The Gherkin) y a Court Rd M r y a Lud gat i St St e H n M d t ill r e o xfo Fle Fenchurch St Monument r ld O i C e O C an n s Jam h on St Tower Hill t h Blackfriars S a r d es St i e Oxford Circus n Aldwyc Temple l a s Edgware Rd Tower Hil g r n Reg Paddington P d ve s St The Monument me G A ha per T y Covent Garden Start x St ent Up r e d t r Hamleys u C en s fo N km Norfolk