The New Negro Movement in Lincoln, Nebraska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia Douglas Johnson and Eulalie Spence As Figures Who Fostered Community in the Midst of Debate

Art versus Propaganda?: Georgia Douglas Johnson and Eulalie Spence as Figures who Fostered Community in the Midst of Debate Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Caroline Roberta Hill, B.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2019 Thesis Committee: Jennifer Schlueter, Adviser Beth Kattelman Copyright by Caroline Roberta Hill 2019 Abstract The Harlem Renaissance and New Negro Movement is a well-documented period in which artistic output by the black community in Harlem, New York, and beyond, surged. On the heels of Reconstruction, a generation of black artists and intellectuals—often the first in their families born after the thirteenth amendment—spearheaded the movement. Using art as a means by which to comprehend and to reclaim aspects of their identity which had been stolen during the Middle Passage, these artists were also living in a time marked by the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and segregation. It stands to reason, then, that the work that has survived from this period is often rife with political and personal motivations. Male figureheads of the movement are often remembered for their divisive debate as to whether or not black art should be politically charged. The public debates between men like W. E. B. Du Bois and Alain Locke often overshadow the actual artistic outputs, many of which are relegated to relative obscurity. Black female artists in particular are overshadowed by their male peers despite their significant interventions. Two pioneers of this period, Georgia Douglas Johnson (1880-1966) and Eulalie Spence (1894-1981), will be the subject of my thesis. -

MFA Boston, Acquisition of Works from Axelrod Collection, Press Release, P

MFA Boston, Acquisition of Works from Axelrod Collection, Press Release, p. 1 Contact: Karen Frascona 617.369.3442 [email protected] MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON, ACQUIRES WORKS BY AFRICAN AMERICAN ARTISTS FROM JOHN AXELROD COLLECTION MFA Marks One-Year Anniversary of Art of the Americas Wing with Display including Works by John Biggers, Eldzier Cortor, and Archibald Motley Jr. BOSTON, MA (November 3, 2011)—Sixty-seven works by African American artists have recently been acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), from collector John Axelrod, an MFA Honorary Overseer and long-time supporter of the Museum. The purchase has enhanced the MFA’s American holdings, transforming it into one of the leading repositories for paintings and sculpture by African American artists. The Museum’s collection will now include works by almost every major African American artist working during the past century and a half. Seven of the works are now displayed in the Art of the Cocktails, about 1926, Archibald Motley Americas Wing, in time for its one-year anniversary this month. This acquisition furthers the Museum’s commitment to showcasing the great multicultural artistry found throughout the Americas. It was made possible with the support of Axelrod and the MFA’s Frank B. Bemis Fund and Charles H. Bayley Fund. Axelrod has also donated his extensive research library of books about African American artists to the Museum, as well as funds to support scholarship. ―This is a proud moment for the MFA. When we opened the Art of the Americas Wing last year, our goal was to reflect the diverse interests and backgrounds of all of our visitors. -

African American Modernist: the Exhibition, the Artist, and His Legacy

Aaron Douglas: African American Modernist 121 Aaron Douglas: African American Modernist: The Exhibition, the Artist, and His Legacy Stephanie Fox Knappe On September 8, 2007, the Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas, Lawrence, opened the first nationally traveling retrospective to com- memorate the art and legacy of Aaron Douglas (1899–1979), the preeminent visual artist of the Harlem Renaissance. Aaron Douglas: African American Modernist reaffirmed his position in the annals of what remains the largely white epic of American modernism and focused new attention on lesser-known facets of the lengthy career of the indefatigable artist. The retrospective of nearly one hundred works in a variety of media from thirty-seven lenders, as well as its accompanying catalogue, conference, and myriad complementary programs, declared the power of Douglas’s distinctive imagery and argued for the lasting potency of his message. This essay provides an opportunity to extend the experience presented by Aaron Douglas: African American Modernist during its fifteen-month tour. Beginning at the Spencer Museum of Art and continuing on to the Frist Center for the Visual Arts in Nashville, and Washington D.C.’s Smithsonian American Art Museum, the exhibition closed on November 30, 2008, at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York. Many of the works that were gathered together for the traveling retrospective with the purpose of showcasing Douglas, his role in American modernism, and his enduring legacy are discussed in this essay. Additionally, to acknowledge that rare is the artist whose work may truly be understood when divorced from the context in which it took root, the 0026-3079/2008/4901/2-121$2.50/0 American Studies, 49:1/2 (Spring/Summer 2008): 121-130 121 122 Stephanie Fox Knappe art that composed Aaron Douglas: African American Modernist is presented here in tandem with key biographical elements. -

=5^, the Monitor —>

• 1 .» .. L si =5^, The Monitor —> %. A NATIONAL WEEKLY NEWSPAPER DEVOTED TO THE INTERESTS OF COLORED AMERICANS THE REV. JOHN ALBERT WILLIAMS. Editor $2.00 a Year. 5c a Copy '\ OMAHA, NEBRASKA, FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 14, 1923 Whole Number 427 Vol. IX—No. 11 HEAR BAGNALL SUNDAY AFTERNOON AT GROVE M. E. CHURCH ON “THE NEW EMANCIPATION” EMANCIPATION DAY PROMINENT AUTHOR UNITE! STATES CELEBRATION DRAWS AND CLERGYMAN COLORED MAH CAN- * Concrete LARGE ATTENDANCE Along the IS OMAHA VISITOR WILL PROTECT Q[ |[~j DIDATE FOR MAYOR Governor Bryan Makes Favorable Rohert W. Bagnall, Director of ITS EMPLOYES Impression By Excellent Branches National Advancement OF PHILADELPHIA Address. Association Speaks Postmaster General Warns Woman Sunday. Race Voters Dissatisfied With Candi- Who Threatened Colored Post- About 2,000 people attended the dates of Both Parties Because man With Bodily Harm If fifth annual emancipation celebration Omaha has as its guest this week They Forget Promises Not Removed. given by St. John’s A. M. E. Churcn Robert W. Bagnall, director of “After Election” at Krug Park Monday. The weather Branches of the National Association WRITES was ideal for such an outing. The for the Advancement of Colored Peo- IE8R0ES EMPHATIC LETTER observance began with a parade of ple, Fr. Bagnall is a priest of the LEUMIO TO HITE • ________ attractively decorated automobiles, im Episcopal church, who for ten years Face the Issues IWIares All Power at Command of headed by a band and a platoon of was rector of St. Matthew’s Church, They Without a Com- Government Will Be Employed colored police officers, through the Detroit, Mich., the home parish of promise and Name J. -

Omaha Monitor April 29 1916

. ~: :'...... .. ••I _: I .'.':••:.:....: •• ~ '.... .. !. .. "" ~. '. ; ". ",: ':-. 0 ITOR :A:WeeklyNew~paperDevoted to the Interests of the Eight Thousand Colored People ". ", '.'" in, Omaha and Vicinity, and to the Good of the Community The'Rev. JOHN ALBERT WILLIAMS, Editor " .' ':"";";"--'"~-:-----""'-:------------------"------------_"':"--_-------- Omaha, Nebraska, April 29, 1916 Volume I. Number 44 ....... .J QI1:itedStatesWar:ship From Fair Nebraska ···:'Itetunls·.From·Liberia.'~ to Sunny Tennessee '. .. .-' .' , Crujs,~r Clie.sterDi~pafched to Africa. Incidents of the Trip and Impression .;Lends,Moral Sup'port to Liberian Received by Editor on First Visit Government.- to Southland. A LEVEL-HEADED PRESIDENT. KEEN GREEKS AND ITALIANS. Commander Schofield Favorably Im The Sons of Italy and Greece Royal . pressed With President Howard. Purveyors to the Palat.es of SeCret~ry" of Legation Re Princes of Ethiopia. ······· ...t~s--onVessei. Who was it, Homer or Virgil, who Bosto~, Mass., April 27.-Sent to sang of "Ethiopia's blameless race "!., the West Coast of Africa '~or the pur- One 'ought not get hazy or rusty on pose of ghting support to:tbe govern- his classics, but, with the lapse <lIf ment of the Republic of tiberia, the leal'S, he does. UnIted States sco~t c~er Chester Well, speaking of the classics, which returnEidto this countrY,' doc~ing at 3.re. going out of style in our modem 'tYie'Bostorr--Navy Yard on Tuesday; (ir educational methods, which stress the ":april 11, after tel1mQnths' absenc·e. "practical" and "utilitarian," and mill-- .On board the vessel as passengers imize intellectual breadth and cultur~, were R. C.Bundy,~secretary of the .we are reminded of the aphorisnil, United States .legation and 'charge '. -

Vanguards of the New Negro: African American Veterans and Post-World War I Racial Militancy Author(S): Chad L

Vanguards of the New Negro: African American Veterans and Post-World War I Racial Militancy Author(s): Chad L. Williams Source: The Journal of African American History, Vol. 92, No. 3 (Summer, 2007), pp. 347- 370 Published by: Association for the Study of African American Life and History Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20064204 Accessed: 19-07-2016 19:37 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20064204?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Association for the Study of African American Life and History is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of African American History This content downloaded from 128.210.126.199 on Tue, 19 Jul 2016 19:37:32 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms VANGUARDS OF THE NEW NEGRO: AFRICAN AMERICAN VETERANS AND POST-WORLD WAR I RACIAL MILITANCY Chad L. Williams* On 28 July 1919 African American war veteran Harry Hay wood, only three months removed from service in the United States Army, found himself in the midst of a maelstrom of violence and destruction on par with what he had experienced on the battlefields of France. -

A History of the Episcopal Church in Omaha from 1856 to 1964

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 1-1-1965 A history of the Episcopal Church in Omaha from 1856 to 1964 James M. Robbins Jr University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Robbins, James M. Jr, "A history of the Episcopal Church in Omaha from 1856 to 1964" (1965). Student Work. 580. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/580 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A HISTORY OF THE EPISCOPAL CHURCH IN OMAHA FROM 1856 TO 1964 A Thesis Presented to the Department of History and the Faculty of the College of Graduate Studies University of Omaha In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts fey James M. Robbins, Jr. January, 1965 UMI Number: EP73218 Alt rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI Dissertation Publishing UMI EP73218 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code uest ProQuest LLC. -

Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain by Langston Hughes

THE NEGRO ARTIST AND THE RACIAL MOUNTAIN BY LANGSTON HUGHES INTRODUCTION celebrated African American creative innovations such BY POETRY FOUNDATION, 2009 as blues, spirituals, jazz, and literary work that engaged African American life. Notes Hughes, “this is the Langston Hughes was a leader of the Harlem mountain standing in the way of any true Negro art in Renaissance of the 1920s. He was educated at America—this urge within the race toward whiteness, Columbia University and Lincoln University. While the desire to pour racial individuality into the mold of a student at Lincoln, he published his first book American standardization, and to be as little Negro of poetry, The Weary Blues (1926), as well as his and as much American as possible.” landmark essay, seen by many as a cornerstone document articulation of the Harlem renaissance, His attention to working-class African-American lives, “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain.” coupled with his refusal to paint these lives as either saintly or stereotypical, brought criticism from several Earlier that year, Freda Kirchwey, editor of the Nation, directions. Articulating the unspoken directives mailed Hughes a proof of “The Negro-Art Hokum,” an he struggled to ignore, Hughes observes, “‘Oh, be essay George Schuyler had written for the magazine, respectable, write about nice people, show how good requesting a counterstatement. Schuyler, editor of we are,’ say the Negroes. ‘Be stereotyped, don’t go too the African-American newspaper The Pittsburgh far, don’t shatter our illusions about you, don’t amuse Courier, questioned in his essay the need for a separate us too seriously. -

Making a Collection'': James Weldon Johnson and The

South Atlantic Quarterly Tess Chakkalakal ‘‘Making a Collection’’: James Weldon Johnson and the Mission of African American Literature Anthology Theory In the preface to the second edition of the Norton Anthology of African-American Literature, the general editors—Henry Louis Gates Jr. and 1 Nellie McKay—come out as ‘‘un-theoretical.’’ Although several of the anthology’s eleven edi- tors were still engaged with theory during the mid-1980s, they explain that the process of actu- ally editing the anthology helped them to real- ize theory’s irrelevance. Their position against theory pits their project against the established realm of literary studies: ‘‘We were embark- ing upon a process of canon formation,’’ they acknowledge, ‘‘precisely when many of our post- structuralist colleagues were questioning the value of the canon itself ’’ (xxx). Of course, it quickly becomes apparent that theory does inform the formation of the an- thology. To simply put various texts written in different times, spaces, and genres together in a single book would not demonstrate the connec- tions between them; it would not satisfactorily constitute African American literature. And that is the project. For the editors view the construc- tion rather than the deconstruction of a literary The South Atlantic Quarterly 104:3, Summer 2005. Copyright © 2005 by Duke University Press. Published by Duke University Press South Atlantic Quarterly 522 Tess Chakkalakal canon as ‘‘essential for the permanent institutionalization of the black liter- ary tradition within departments of English, American Studies, and African American Studies’’ (xxix). This essay is an attempt to illuminate this claim by the editors of the Norton not by analyzing the texts that the editors select for inclusion, but by considering both the impulse to collect various literary texts to form a single entity called ‘‘African American literature’’ and its impact on our understanding of literature as such. -

'Poet on Poet': Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes

ANGLOGERMANICA ONLINE 2007. Millanes Vaquero, Mario: ‘Poet on Poet’: Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes (Two Versions for an Aesthetic-Literary Theory) ____________________________________________________________________________________ ‘Poet on Poet’: Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes (Two Versions for an Aesthetic-Literary Theory) Mario Millanes Vaquero, Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Spain) If I am going to be a poet at all, I am going to be POET and not NEGRO POET. Countee Cullen A poet is a human being. Each human being must live within his time, with and for his people, and within the boundaries of his country. Langston Hughes Because the Negro American writer is the bearer of two cultures, he is also the guardian of two literary traditions. Robert Bone Index 1 Introduction 2 Poet on Poet 3 Africa, Friendship, and Gay Voices 4 The (Negro) Poet 5 Conclusions Bibliography 1 Introduction Countee Cullen (1903-1946) and Langston Hughes (1902-1967) were two of the major figures of a movement later known as the Harlem Renaissance. Although both would share the same artistic circle and play an important role in it, Cullen’s reputation was eclipsed by that of Hughes for many years after his death. Fortunately, a number of scholars have begun to clarify their places in literary history. I intend to explain the main aspects in which their creative visions differ: Basically, Cullen’s traditional style and themes, and Hughes’s use of blues, jazz, and vernacular. I will focus on their debut books, Color (1925), and The Weary Blues (1926), respectively. 2 Poet on Poet A review of The Weary Blues appeared in Opportunity on 4 March, 1926. -

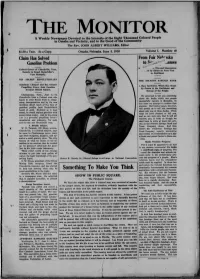

The Monitor a Weekly Newspaper Devoted to the Interests of the Eight Thousand Colored People in Omaha and Vicinity, and to the Good of the Community the Rev

The Monitor A Weekly Newspaper Devoted to the Interests of the Eight Thousand Colored People in Omaha and Vicinity, and to the Good of the Community The Rev. JOHN ALBERT WILLIAMS, Editor Volume I. Number 49 $1.50 a Year. 5c a Copy. Omaha, Nebraska, June 3, 1916 Claim Has Solved From Fair Ne^ska Gasoline Problem to S»’;^scC ^essee p Ii ..e Trip and Impressions Colored Grocer of Churchville, Tenn., .,ed by Editor on First Visit to Smash Rockefeller’s Expects to Southland. Vast Monopoly. HIS SECRET REVOLUTIONARY THE SOLVENT SAVINGS BANK Substitute Cheaper and has Greater A Race Institution Which Has Stead- Propelling Power than Gasoline ily Grown in the Confidence and Inventor British Subject. Esteem of the People. Chattanooga, Tenn., June 3.—In We promised to tell you something Churchville lives a Colored man who about the banks which our people hopes to rival Henry Ford in cheap- successfully operate in Memphis. In ening transportation and by his own this issue we attempt to redeem that invention divert much of the flow of promise. Our limited space, however, gasoline profits from Rockefeller's will permit us to tell you something hoard of gold. Mythical as it may about only one of these banks. From sound, he would replace gasoline with what we have planned to tell you, green-tinted water. And in the green and we are very sure that it will all tint is a powerful propelling force— interest you, it looks as though we and ’tis unpatented unknown, said, shall have to write at least two arti- save to the one Churchville man. -

The Judgment Day 1939 Oil on Tempered Hardboard Overall: 121.92 × 91.44 Cm (48 × 36 In.) Inscription: Lower Right: A

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS American Paintings, 1900–1945 Aaron Douglas American, 1899 - 1979 The Judgment Day 1939 oil on tempered hardboard overall: 121.92 × 91.44 cm (48 × 36 in.) Inscription: lower right: A. Douglas '39 Patrons' Permanent Fund, The Avalon Fund 2014.135.1 ENTRY Aaron Douglas spent his formative years in the Midwest. Born and raised in Topeka, Kansas, he attended a segregated elementary school and an integrated high school before entering the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. In 1922 he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in fine arts, and the following year he accepted a teaching position at Lincoln High School, an elite black institution in Kansas City. Word of Douglas’s talent and ambition soon reached influential figures in New York including Charles Spurgeon Johnson (1893–1956), one of the founders of the New Negro movement. [1] Johnson instructed his secretary, Ethel Nance, to write to the young artist encouraging him to come east (“Better to be a dishwasher in New York than to be head of a high school in Kansas City"). [2] In the spring of 1925, after two years of teaching, Douglas resigned his position and began the journey that would place him at the center of the burgeoning cultural movement later known as the Harlem Renaissance. [3] Douglas arrived in New York three months after an important periodical, Survey Graphic, published a special issue titled Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro. [4] A landmark publication, the issue included articles by key members of the New Negro movement: Charles S.