JBHE Foundation, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia Douglas Johnson and Eulalie Spence As Figures Who Fostered Community in the Midst of Debate

Art versus Propaganda?: Georgia Douglas Johnson and Eulalie Spence as Figures who Fostered Community in the Midst of Debate Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Caroline Roberta Hill, B.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2019 Thesis Committee: Jennifer Schlueter, Adviser Beth Kattelman Copyright by Caroline Roberta Hill 2019 Abstract The Harlem Renaissance and New Negro Movement is a well-documented period in which artistic output by the black community in Harlem, New York, and beyond, surged. On the heels of Reconstruction, a generation of black artists and intellectuals—often the first in their families born after the thirteenth amendment—spearheaded the movement. Using art as a means by which to comprehend and to reclaim aspects of their identity which had been stolen during the Middle Passage, these artists were also living in a time marked by the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and segregation. It stands to reason, then, that the work that has survived from this period is often rife with political and personal motivations. Male figureheads of the movement are often remembered for their divisive debate as to whether or not black art should be politically charged. The public debates between men like W. E. B. Du Bois and Alain Locke often overshadow the actual artistic outputs, many of which are relegated to relative obscurity. Black female artists in particular are overshadowed by their male peers despite their significant interventions. Two pioneers of this period, Georgia Douglas Johnson (1880-1966) and Eulalie Spence (1894-1981), will be the subject of my thesis. -

Vanguards of the New Negro: African American Veterans and Post-World War I Racial Militancy Author(S): Chad L

Vanguards of the New Negro: African American Veterans and Post-World War I Racial Militancy Author(s): Chad L. Williams Source: The Journal of African American History, Vol. 92, No. 3 (Summer, 2007), pp. 347- 370 Published by: Association for the Study of African American Life and History Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20064204 Accessed: 19-07-2016 19:37 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20064204?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Association for the Study of African American Life and History is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of African American History This content downloaded from 128.210.126.199 on Tue, 19 Jul 2016 19:37:32 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms VANGUARDS OF THE NEW NEGRO: AFRICAN AMERICAN VETERANS AND POST-WORLD WAR I RACIAL MILITANCY Chad L. Williams* On 28 July 1919 African American war veteran Harry Hay wood, only three months removed from service in the United States Army, found himself in the midst of a maelstrom of violence and destruction on par with what he had experienced on the battlefields of France. -

Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain by Langston Hughes

THE NEGRO ARTIST AND THE RACIAL MOUNTAIN BY LANGSTON HUGHES INTRODUCTION celebrated African American creative innovations such BY POETRY FOUNDATION, 2009 as blues, spirituals, jazz, and literary work that engaged African American life. Notes Hughes, “this is the Langston Hughes was a leader of the Harlem mountain standing in the way of any true Negro art in Renaissance of the 1920s. He was educated at America—this urge within the race toward whiteness, Columbia University and Lincoln University. While the desire to pour racial individuality into the mold of a student at Lincoln, he published his first book American standardization, and to be as little Negro of poetry, The Weary Blues (1926), as well as his and as much American as possible.” landmark essay, seen by many as a cornerstone document articulation of the Harlem renaissance, His attention to working-class African-American lives, “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain.” coupled with his refusal to paint these lives as either saintly or stereotypical, brought criticism from several Earlier that year, Freda Kirchwey, editor of the Nation, directions. Articulating the unspoken directives mailed Hughes a proof of “The Negro-Art Hokum,” an he struggled to ignore, Hughes observes, “‘Oh, be essay George Schuyler had written for the magazine, respectable, write about nice people, show how good requesting a counterstatement. Schuyler, editor of we are,’ say the Negroes. ‘Be stereotyped, don’t go too the African-American newspaper The Pittsburgh far, don’t shatter our illusions about you, don’t amuse Courier, questioned in his essay the need for a separate us too seriously. -

Making a Collection'': James Weldon Johnson and The

South Atlantic Quarterly Tess Chakkalakal ‘‘Making a Collection’’: James Weldon Johnson and the Mission of African American Literature Anthology Theory In the preface to the second edition of the Norton Anthology of African-American Literature, the general editors—Henry Louis Gates Jr. and 1 Nellie McKay—come out as ‘‘un-theoretical.’’ Although several of the anthology’s eleven edi- tors were still engaged with theory during the mid-1980s, they explain that the process of actu- ally editing the anthology helped them to real- ize theory’s irrelevance. Their position against theory pits their project against the established realm of literary studies: ‘‘We were embark- ing upon a process of canon formation,’’ they acknowledge, ‘‘precisely when many of our post- structuralist colleagues were questioning the value of the canon itself ’’ (xxx). Of course, it quickly becomes apparent that theory does inform the formation of the an- thology. To simply put various texts written in different times, spaces, and genres together in a single book would not demonstrate the connec- tions between them; it would not satisfactorily constitute African American literature. And that is the project. For the editors view the construc- tion rather than the deconstruction of a literary The South Atlantic Quarterly 104:3, Summer 2005. Copyright © 2005 by Duke University Press. Published by Duke University Press South Atlantic Quarterly 522 Tess Chakkalakal canon as ‘‘essential for the permanent institutionalization of the black liter- ary tradition within departments of English, American Studies, and African American Studies’’ (xxix). This essay is an attempt to illuminate this claim by the editors of the Norton not by analyzing the texts that the editors select for inclusion, but by considering both the impulse to collect various literary texts to form a single entity called ‘‘African American literature’’ and its impact on our understanding of literature as such. -

'Poet on Poet': Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes

ANGLOGERMANICA ONLINE 2007. Millanes Vaquero, Mario: ‘Poet on Poet’: Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes (Two Versions for an Aesthetic-Literary Theory) ____________________________________________________________________________________ ‘Poet on Poet’: Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes (Two Versions for an Aesthetic-Literary Theory) Mario Millanes Vaquero, Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Spain) If I am going to be a poet at all, I am going to be POET and not NEGRO POET. Countee Cullen A poet is a human being. Each human being must live within his time, with and for his people, and within the boundaries of his country. Langston Hughes Because the Negro American writer is the bearer of two cultures, he is also the guardian of two literary traditions. Robert Bone Index 1 Introduction 2 Poet on Poet 3 Africa, Friendship, and Gay Voices 4 The (Negro) Poet 5 Conclusions Bibliography 1 Introduction Countee Cullen (1903-1946) and Langston Hughes (1902-1967) were two of the major figures of a movement later known as the Harlem Renaissance. Although both would share the same artistic circle and play an important role in it, Cullen’s reputation was eclipsed by that of Hughes for many years after his death. Fortunately, a number of scholars have begun to clarify their places in literary history. I intend to explain the main aspects in which their creative visions differ: Basically, Cullen’s traditional style and themes, and Hughes’s use of blues, jazz, and vernacular. I will focus on their debut books, Color (1925), and The Weary Blues (1926), respectively. 2 Poet on Poet A review of The Weary Blues appeared in Opportunity on 4 March, 1926. -

Politics, Identity and Humor in the Work of Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Sholem Aleichem and Mordkhe Spector

The Artist and the Folk: Politics, Identity and Humor in the Work of Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Sholem Aleichem and Mordkhe Spector by Alexandra Hoffman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Comparative Literature) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Professor Anita Norich, Chair Professor Sandra Gunning Associate Professor Mikhail Krutikov Associate Professor Christi Merrill Associate Professor Joshua Miller Acknowledgements I am delighted that the writing process was only occasionally a lonely affair, since I’ve had the privilege of having a generous committee, a great range of inspiring instructors and fellow graduate students, and intelligent students. The burden of producing an original piece of scholarship was made less daunting through collaboration with these wonderful people. In many ways this text is a web I weaved out of the combination of our thoughts, expressions, arguments and conversations. I thank Professor Sandra Gunning for her encouragement, her commitment to interdisciplinarity, and her practical guidance; she never made me doubt that what I’m doing is important. I thank Professor Mikhail Krutikov for his seemingly boundless references, broad vision, for introducing me to the oral history project in Ukraine, and for his laughter. I thank Professor Christi Merrill for challenging as well as reassuring me in reading and writing theory, for being interested in humor, and for being creative in not only the academic sphere. I thank Professor Joshua Miller for his kind and engaged reading, his comparative work, and his supportive advice. Professor Anita Norich has been a reliable and encouraging mentor from the start; I thank her for her careful reading and challenging comments, and for making Ann Arbor feel more like home. -

African-Americana Between the Covers

BETWEEN THE COVERS RARE BOOKS CATALOG 186 AFRICAN-AMERICANA AFRICAN-AMERICANA An Inscribed Copy 1 Francis E.W. HARPER Iola Leroy, or Shadows Uplifted Philadelphia: Garrigues Brothers 1892 First edition. Brown cloth gilt. Frontispiece portrait of the author (occasionally lacking). Introduction by William Still. A fine copy with just the slightest of bumping at the corners and hinge repaired, the gilt bright and unrubbed. Small stamp of the Anti-Slavery and Aborigines Protection Society on first blank, and beneath that Inscribed by Harper in pencil: “C. Impey. Street Somerset 1893 from the Author (and Publisher W. Still)”. The only novel by Harper, better known for her poetry and essays, this was long considered the first novel to be published by an African-American woman, until Henry Louis Gates, Jr. advanced the cause of Harriet E. Wilson’s Our Nig (1859). Although this novel contains many conventional elements, it also concerns itself with the personal independence of women of color, and particularly of the race in general. The protagonist, the daughter of a wealthy white father, is unaware that her mother is not only mulatto, but also the property of the husband. When her father dies, her uncle claims them as slaves. After being liberated by the Union Army, she offers her services as a nurse, and attracts the attentions of a white doctor, who discovers she is of mixed race, and encourages her to “pass” for white, which she rejects, setting off to seek her parents accompanied by a light-skinned black doctor instead. The inscription in this copy is to Catherine Impey (of Street Somerset) a British Quaker activist against racial discrimination who founded Britain’s first anti-racist journal,Anti-Caste , in 1888. -

“The Harlem Renaissance: Rebirth of African-American Arts” Westbury Arts Celebrates Dr

“The Harlem Renaissance: Rebirth of African-American Arts” Westbury Arts Celebrates Dr. Alain LeRoy Locke (1885 – 1954) Photo taken by Gordon Parks/The Gordon Parks Foundation “Nothing is more galvanizing than the sense of a cultural past” Alain Locke Alain LeRoy Locke is considered the “Father of the Harlem Renaissance.” Locke was a leading intellectual during the early twentieth century and is best known as a theorist, critic, and interpreter of African American literature and art. His essays, books and magazine articles called attention to the development of Harlem, the neighborhood in New York City, which became a black cultural mecca in the early 20th Century, and he chronicled the social and artistic revolution that resulted there. Lasting from the 1910s through the mid-1930s, the period is considered a golden age in African American culture, manifested in literature, music, stage performance and art. Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1885, Locke was an only child and his father, Pliny Ismael Locke, despite having a law degree, worked as a mail clerk. His father died when Locke was 6 years old, but his mother, Mary Hawkins Locke who worked as a teacher, attempted to provide a middle-class life for Alain and raised her son, from the time he was 6, to play the aristocrat. Locke grew up determined to demonstrate his worth by cultivating a reverence for the arts. He was educated among wealthy students at one of the city’s finest public high schools and enrolled at Harvard at 19. In his lifetime, Locke had many important accomplishments. He earned his bachelor's degree from Harvard University completing a four-year philosophy degree in only three years and graduating magna cum laude. -

Celebrating the Harlem Renaissance Season” with the Irving Black Arts Council What Is the Harlem Renaissance?

An Introduction to the Harlem Renaissance Presented by the Irving Arts Center in association with the 2009-2010 “Celebrating the Harlem Renaissance Season” with the Irving Black Arts Council What is the Harlem Renaissance? The Harlem Renaissance was an African American cultural movement that began in Harlem, New York after World War I and ended during the late 1930s. What is the Harlem Renaissance? The Harlem Renaissance marked the first time that mainstream publishers and critics took African American literature seriously and that African American literature and arts attracted significant attention from the nation at large. Literature During the Harlem Renaissance African American literature changed during the Harlem Renaissance--for the first time, the writing of the blacks dealt with exploring their own culture on a deeper and more complicated level. The writing of the Harlem Renaissance expressed a pride in being black and a growing sense of confidence among African Americans. Writers of the Harlem Renaissance Black literary writers covered such issues as black life in the South and the North, racial identity, racial issues, and equality through poetry, prose, novels, and fiction. Some of the more popular writers tackling these issues included Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, and Jessie Redmon Fauset. Zora Neale Hurston Langston Hughes Countee Cullen Jessie Redmon Fauset Leading Intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance During this pivotal period, the Harlem Renaissance fostered black pride and uplifting of the race through the use of intellect. Thinking African-Americans, using artistic talents, challenged racial stereotypes and helped promote racial integration. Significantly, the genesis of the Civil Rights movement was rooted in radical political ideologies of Harlem Renaissance intellectuals. -

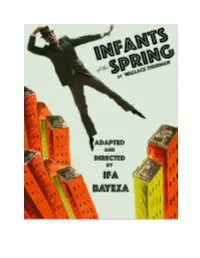

Infants of the Spring Student Matinee

Study Guide for Infants of the Spring Student Matinee by Priscilla Page and Shaila Schmidt CONTENTS Playwright’s Bio Novelist’s Bio Portrait Of The Artist As A Young Black Man by Ifa Bayeza The N Word: History, Culture, and Context by Priscilla Page Overview of Harlem Renaissance Overview of The Jazz Age Who’s Who of Harlem Renaissance Race and Racial Violence: • Birth of a Nation, D.W. Griffith, 1915 • The Jim Crow Era Racial Violence in the North: How New York City Became The Capital of the Jim Crow North Black Organizing and Resistance: • NAACP • United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) Glossary Ifa Bayeza is an award-winning theater artist and novelist. Her critically acclaimed drama The Ballad of Emmett Till premiered at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago and was awarded a Eugene O'Neill National Playwrights Conference fellowship and the Mystery Writers of America Edgar Award for Best Play. The Ballad made its West Coast premiere at the Fountain Theatre in Los Angeles, garnering six Ovation Awards, including Best Production; four Drama Desk Critics' Circle Awards, including Best Production; and the Backstage Garland Award for Best Playwriting. After numerous critically acclaimed regional productions, Bayeza expanded The Ballad into The Till Trilogy, recounting the epic Civil Rights saga in three distinct dramas. In June 2018, Mosaic Theatre in Washington DC will present for the first time all three plays, The Ballad of Emmett Till, benevolence and That Summer in Sumner. Other innovative works for the stage include Ta'zieh – Between Two Rivers; Welcome to Wandaland; String Theory and Homer G & the Rhapsodies in The Fall of Detroit, for which she received a Kennedy Center Fund for New American Plays Award. -

Destabilizing Sexuality and Gender Constructs of the New Negro Identity in Harlem Renaissance Literature

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 6-1-2012 "A Shade Too Unreserved": Destabilizing Sexuality and Gender Constructs of the New Negro Identity in Harlem Renaissance Literature Renee E. Chase University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Chase, Renee E., ""A Shade Too Unreserved": Destabilizing Sexuality and Gender Constructs of the New Negro Identity in Harlem Renaissance Literature" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 121. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/121 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. “A SHADE TOO UNRESERVED”: DESTABILIZING SEXUALITY AND GENDER CONSTRUCTS OF THE NEW NEGRO IDENTITY IN HARLEM RENAISSANCE LITERATURE __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Renee E. Chase June 2012 Advisor: Dr. Maik Nwosu ©Copyright by Renee E. Chase 2012 All Rights Reserved Author: Renee E. Chase Title: “A SHADE TOO UNRESERVED”: DESTABILIZING SEXUALITY AND GENDER CONSTRUCTS OF THE NEW NEGRO IDENTITY IN HARLEM RENAISSANCE LITERATURE Advisor: Dr. Maik Nwosu Degree Date: June 2012 Abstract Much of the Harlem Renaissance artistic movement was directly intertwined with the New Negro social movement of the time. -

Rene Maran and the New Negro

Colby Quarterly Volume 15 Issue 4 December Article 4 December 1979 Rene Maran and the New Negro Chidi Ikonne Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 15, no.4, December 1979, p.224-239 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Ikonne: Rene Maran and the New Negro Rene Maran and the New Negro by CHIDI IKONNE NE OF THE items that catch the eye in Locke Archives, Moor O land-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, is a photo graph with the inscription: A mon excellent ami Alain Leroy Locke, Son ami Paris, 28/8/26 Rene Maran. When Mercer Cook visited Rene Maran for the first time, one of the things that arrested his attention in Maran's apartment in Paris was also a photograph: that of Alain Locke "prominently placed in [Maran's] home" as an evidence not only of the French West Indian writer's "in terest in the race question," 1 but also of his personal feelings towards the Dean of the New Negro Literary Movement. Rene Maran always prized his friendship with Locke very highly. Locke's anthology The New Negro occupied a prominent place in his library; he did his best to get it translated into French. 2 Rene Maran regularly received and read such Afro-American journals as Opportunity, The Crisis, The Negro World, and Chicago Defender which carried news (complimentary or adverse) about the New Negro.