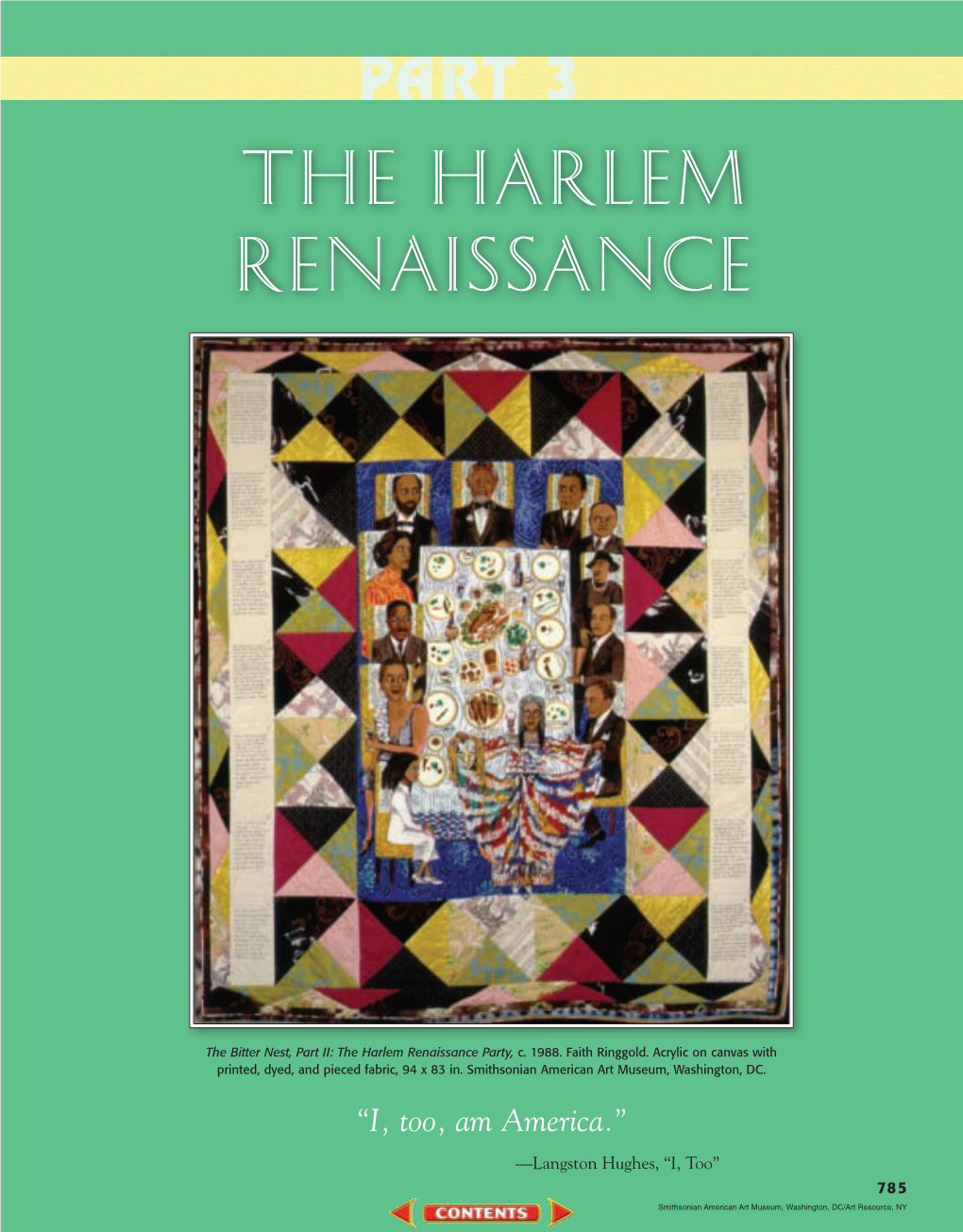

The Harlem Renaissance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia Douglas Johnson and Eulalie Spence As Figures Who Fostered Community in the Midst of Debate

Art versus Propaganda?: Georgia Douglas Johnson and Eulalie Spence as Figures who Fostered Community in the Midst of Debate Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Caroline Roberta Hill, B.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2019 Thesis Committee: Jennifer Schlueter, Adviser Beth Kattelman Copyright by Caroline Roberta Hill 2019 Abstract The Harlem Renaissance and New Negro Movement is a well-documented period in which artistic output by the black community in Harlem, New York, and beyond, surged. On the heels of Reconstruction, a generation of black artists and intellectuals—often the first in their families born after the thirteenth amendment—spearheaded the movement. Using art as a means by which to comprehend and to reclaim aspects of their identity which had been stolen during the Middle Passage, these artists were also living in a time marked by the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and segregation. It stands to reason, then, that the work that has survived from this period is often rife with political and personal motivations. Male figureheads of the movement are often remembered for their divisive debate as to whether or not black art should be politically charged. The public debates between men like W. E. B. Du Bois and Alain Locke often overshadow the actual artistic outputs, many of which are relegated to relative obscurity. Black female artists in particular are overshadowed by their male peers despite their significant interventions. Two pioneers of this period, Georgia Douglas Johnson (1880-1966) and Eulalie Spence (1894-1981), will be the subject of my thesis. -

Questionnaire Responses Emily Bernard

Questionnaire Responses Emily Bernard Modernism/modernity, Volume 20, Number 3, September 2013, pp. 435-436 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/mod.2013.0083 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/525154 [ Access provided at 1 Oct 2021 22:28 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] questionnaire responses ments of the productions of the Harlem Renaissance? How is what might be deemed 435 a “multilingual mode of study” vital for our present day work on the movement? The prospect of a center for the study of the Harlem Renaissance is terribly intriguing for future scholarly endeavors. Houston A. Baker is Distinguished University Professor and a professor of English at Vander- bilt University. He has served as president of the Modern Language Association of America and is the author of articles, books, and essays devoted to African American literary criticism and theory. His book Betrayal: How Black Intellectuals Have Abandoned the Ideals of the Civil Rights Era (2008) received an American Book Award for 2009. Emily Bernard How have your ideas about the Harlem Renaissance evolved since you first began writing about it? My ideas about the Harlem Renaissance haven’t changed much in the last twenty years, but they have expanded. I began reading and writing about the Harlem Renais- sance while I was still in college. I was initially drawn to it because of its surfaces—styl- ish people in attractive clothing, the elegant interiors and exteriors of its nightclubs and magazines. Style drew me in, but as I began to read and write more, it wasn’t the style itself but the intriguing degree of importance assigned to the issue of style that kept me interested in the Harlem Renaissance. -

HARLEM in SHAKESPEARE and SHAKESPEARE in HARLEM: the SONNETS of CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, and GWENDOLYN BROOKS David J

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 5-1-2015 HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS David J. Leitner Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Leitner, David J., "HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS" (2015). Dissertations. Paper 1012. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS by David Leitner B.A., University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana, 1999 M.A., Southern Illinois University Carbondale, 2005 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Department of English in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2015 DISSERTATION APPROVAL HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS By David Leitner A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Approved by: Edward Brunner, Chair Robert Fox Mary Ellen Lamb Novotny Lawrence Ryan Netzley Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April 10, 2015 AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF DAVID LEITNER, for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in ENGLISH, presented on April 10, 2015, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. -

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project

preciate it if you could find it for me.5 I am happy to say that I have read most of zg Dec Gandhi’s works and I have most of them in my library. ‘959 Incidentally, I have written a book entitled Stride Toward Freedom. One of the chapters is devoted to my pilgrimage to nonviolence. Here I try to show the Gand- hian influence in my thinking. I regret that I sent my last copy out a few days ago. If you are interested, however, you may secure a copy from Harper and Brothers. It was published in September, 1958. I will highly appreciate your comments. In answer to your question concerning China, I definitely feel that it should be admitted to the United Nations. We will never have an effective United Nations so long as the largest nation in the world is not in it. Thanks again for your kind letter, and I hope for you a joyous Christmas sea- son and a blessed new year. Yours very truly, Martin L. King, Jr. (Dictated, but not personally signed by Dr. King.) TLc. MLKP-MBU: Box 72. 3. Gandhi, Gandhi’s Letters to a Disciple (New York: Harper, 1950). In a 2 November 1960letter to King, Teek-Frank indicated that she had learned that the book was out of print but offered to lend him her copy the next time he visited New York. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project To Langston Hughes 29 December 1959 Montgomery, Ala. King thanks Hughes for contributing a poem to A. -

1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconnaissance Survey

1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconnaissance Survey Final November 2005 National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 Summary Statement 1 Bac.ground and Purpose 1 HISTORIC CONTEXT 5 National Persp4l<live 5 1'k"Y v. f~u,on' World War I: 1896-1917 5 World W~r I and Postw~r ( r.: 1!1t7' EarIV 1920,; 8 Tulsa RaCR Riot 14 IIa<kground 14 TI\oe R~~ Riot 18 AIt. rmath 29 Socilot Political, lind Economic Impa<tsJRamlt;catlon, 32 INVENTORY 39 Survey Arf!a 39 Historic Greenwood Area 39 Anla Oubi" of HiOlorK G_nwood 40 The Tulsa Race Riot Maps 43 Slirvey Area Historic Resources 43 HI STORIC GREENWOOD AREA RESOURCeS 7J EVALUATION Of NATIONAL SIGNIFICANCE 91 Criteria for National Significance 91 Nalional Signifiunce EV;1lu;1tio.n 92 NMiol\ill Sionlflcao<e An.aIYS;s 92 Inl~ri ly E~alualion AnalY'is 95 {"",Iu,ion 98 Potenl l~1 M~na~menl Strategies for Resource Prote<tion 99 PREPARERS AND CONSULTANTS 103 BIBUOGRAPHY 105 APPENDIX A, Inventory of Elltant Cultural Resoun:es Associated with 1921 Tulsa Race Riot That Are Located Outside of Historic Greenwood Area 109 Maps 49 The African American S«tion. 1921 51 TI\oe Seed. of c..taotrophe 53 T.... Riot Erupt! SS ~I,.,t Blood 57 NiOhl Fiohlino 59 rM Inva.ion 01 iliad. TIll ... 61 TM fighl for Standp''''' Hill 63 W.II of fire 65 Arri~.. , of the Statl! Troop< 6 7 Fil'lal FiOlrtino ~nd M~,,;~I I.IIw 69 jii INTRODUCTION Summary Statement n~sed in its history. -

Hubert H. Harrison Papers, 1893-1927 MS# 1411

Hubert H. Harrison Papers, 1893-1927 MS# 1411 ©2007 Columbia University Libraries SUMMARY INFORMATION Creator Harrson, Hubert H. Title and dates Hubert H. Harrison Papers, 1893-1927 Abstract Size 23 linear ft. (19 doucument boxes; 7 record storage cartons; 1 flat box) Call number MS# 1411 Location Columbia University Butler Library, 6th Floor Rare Book and Manuscript Library 535 West 114th Street New York, NY 10027 Hubert H. Harrison Papers Languages of material English, French, Latin Biographical Note Born April 27, 1883, in Concordia, St. Croix, Danish West Indies, Hubert H. Harrison was a brilliant and influential writer, orator, educator, critic, and political activist in Harlem during the early decades of the 20th century. He played unique, signal roles, in what were the largest class radical movement (socialism) and the largest race radical movement (the New Negro/Garvey movement) of his era. Labor and civil rights activist A. Philip Randolph described him as “the father of Harlem radicalism” and historian Joel A. Rogers considered him “the foremost Afro-American intellect of his time” and “one of America’s greatest minds.” Following his December 17, 1927, death due to complications of an appendectomy, Harrison’s important contributions to intellectual and radical thought were much neglected. In 1900 Harrison moved to New York City where he worked low-paying jobs, attended high school, and became interested in freethought and socialism. His first of many published letters to the editor appeared in the New York Times in 1903. During his first decade in New York the autodidactic Harrison read and wrote constantly and was active in Black intellectual circles at St. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION N APRIL 1972 THE GOVERNMENT of Senegal inaugurated an exhibition of art by Pablo Picasso at the Musée Dynamique I near downtown Dakar (figure 1).1 Only sparse visual documen- tation of the exhibition has survived, but the details of the exhibi- tion ended up mattering less than did its catalytic function for reassessing, in Dakar, the direction and scope of art nègre—or “black art.”2 By 1972 “black art,” a category with its own circuitous genealogy dating from the early twentieth century, had come to encompass canonical African sculpture as well as modern painting and sculpture by artists of African descent. The category’s critical reassessment took place mainly through a conference, “Picasso, Art Nègre, et Civilisation de l’Universel” (Picasso, black art, and civilization of the universal), organized in conjunction with the Dakar exhibition and featuring prominent artists and intellectuals from Senegal and France.3 At the conference, African sculpture held a pivotal place in discussions of Picasso’s practice, which, in turn, became a contested terrain where the stakes of African mod- ernism were up for debate. 1 60870txt.indd 1 20-02-13 5:44 AM figure 1 Pablo Picasso, exhibition poster, Musée Dynamique, Dakar, 1972, lithograph, 21 ½ × 30 in. Henri Deschamps Lithographie; printed by Mourlot, Paris. Private collection. Artwork © 2020 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Lyan’lex Bernales. 60870txt.indd 2 20-02-13 5:44 AM Given dominant scholarly characterizations of African modernist movements as territorially nationalist, anticolonialist, future-facing, and in many respects opposi- tional toward modernism in the West, it might seem infelicitous to focus on Africans and Europeans contemplating Picasso in postcolonial Dakar. -

The Harlem Renaissance: a Handbook

.1,::! THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY ELLA 0. WILLIAMS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA JULY 1987 3 ABSTRACT HUMANITIES WILLIAMS, ELLA 0. M.A. NEW YORK UNIVERSITY, 1957 THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK Advisor: Professor Richard A. Long Dissertation dated July, 1987 The object of this study is to help instructors articulate and communicate the value of the arts created during the Harlem Renaissance. It focuses on earlier events such as W. E. B. Du Bois’ editorship of The Crisis and some follow-up of major discussions beyond the period. The handbook also investigates and compiles a large segment of scholarship devoted to the historical and cultural activities of the Harlem Renaissance (1910—1940). The study discusses the “New Negro” and the use of the term. The men who lived and wrote during the era identified themselves as intellectuals and called the rapid growth of literary talent the “Harlem Renaissance.” Alain Locke’s The New Negro (1925) and James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan (1930) documented the activities of the intellectuals as they lived through the era and as they themselves were developing the history of Afro-American culture. Theatre, music and drama flourished, but in the fields of prose and poetry names such as Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Zora Neale Hurston typify the Harlem Renaissance movement. (C) 1987 Ella 0. Williams All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special recognition must be given to several individuals whose assistance was invaluable to the presentation of this study. -

Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison: Conflicting Masculinities

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1994 Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison: Conflicting Masculinities H. Alexander Nejako College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Nejako, H. Alexander, "Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison: Conflicting Masculinities" (1994). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625892. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-nehz-v842 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RICHARD WRIGHT AND RALPH ELLISON: CONFLICTING MASCULINITIES A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by H. Alexander Nejako 1994 ProQuest Number: 10629319 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10629319 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

John Lowe Louisiana State University

University of Bucharest Review Vol. XI, no. 1, 2009 John Lowe Louisiana State University Calypso Magnolia: Transience and Durability in the Global South1 Keywords: circumCaribbean literature; Haitian revolution; Southern literary canon; slavery; U.S. South Abstract: The transnational turn in U.S. literary and cultural studies has led to a new consideration of the Atlantic world, particularly of the circumCaribbean, which has been the theatre for some of the most dramatic events of Atlantic history. Haiti, as a nexus for revolution, racial turmoil, and colonial and postcolonial struggle, has always been a lodestar for Southern and circumCaribbean writers. This paper briefly considers links between the U.S. South and the Caribbean, and then examines many examples of the ways in which the Haitian Revolution was reflected in both well-known and more obscure works of U.S. Southern and Caribbean literature, focusing on writers such as Séjour, Cable, Bontemps, Faulkner, Carpentier, Glissant, and James. The concluding section demonstrates how the contemporary Southern writer Madison Smartt Bell drew on this rich literary vein to create his magnificent trilogy on the Haitian Revolution, which begins with the text considered here, All Souls Rising. I also argue that this new configuration of region and cultural history has had and will have future consequences for the status of “durable” and “transient” notions of literary canons. One of the salutary effects of transnationalism/globalization has been the rethinking of nation and national boundaries. The rise of multi-national entities of all kinds and the advent of transnational markets has shaken us into an awareness that cultural configurations have always ignored real and imaginary sovereign boundaries. -

MILLER, KELLY, 1863-1939. Kelly Miller Family Papers, 1890-1989

MILLER, KELLY, 1863-1939. Kelly Miller family papers, 1890-1989 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Miller, Kelly, 1863-1939. Title: Kelly Miller family papers, 1890-1989 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1050 Extent: 22.25 linear feet (46 boxes), 15 bound volumes (BV), and 2 oversized papers boxes (OP) Abstract: Papers of African American intellectual and professor Kelly Miller, including correspondence, writings, subject files, printed material, photographs and other papers, in addition to the papers of his wife Annie Mae Miller, and children. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Unrestricted access. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Related Materials in Other Repositories Kelly Miller papers, Howard University, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center (Washington, D.C.) Separated Material In Emory's holdings are books and pamphlets formerly owned by Kelly Miller. These materials may be located in the Emory University online catalog by searching for: Miller, Kelly, former owner. The May Miller papers were originally received as part of this collection and separated to form their own collection due to their size, research value, and distinct provenance. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Kelly Miller family papers, 1894-1989 Manuscript Collection No. 1050 Source Purchase, 2007. Citation [after identification of item(s)], Kelly Miller family papers, Stuart A. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR.