Recruited by Boko Haram

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sambisa Final Draftnh

Total Aerial Count of Elephants and other Wildlife Species in Sambisa Game Reserve in Borno State, Nigeria By P. Omondi1, R. Mayienda2, Mamza, J.S.3, M.S. Massalatchi4 All correspondences E-mail: [email protected] JULY 2006 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................................. 5 OBJECTIVES OF THE SURVEY .................................................................................................................................. 6 STUDY AREA..................................................................................................................................................................... 7 CLIMATE ........................................................................................................................................................................... 7 SOIL................................................................................................................................................................................... 8 FLORA & FAUNA .............................................................................................................................................................. 8 METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................................................................ -

Early Warning Bulletin

MARCH 2017 EARLY WARNING ISSUE NO.2 BULLETIN Adamawa & Borno States, Nigeria March 2017 Introduction: Attacks by members of Boko At least thirteen Local identified in the month were: Haram and its splinter Government Areas (LGAs) sexual and gender basedviolence group-Islamic State West Africa namely Damboa, Chibok, targeted at both male and female Province (ISWAP) were the Magumeri, Gubio, Marte, minors; humanitarian risks highest threat to peace and Askira-Uba, Ngazai, Mafa, Bama, including fire incidents and security in Adamawa and Borno Kounduga, Monguno, Maiduguri protest by internally displaced states in the month. Twenty and Jere recorded an incident. persons among others. insurgent attacks were recorded Damboa LGA recorded at least in the early warning hub in four attacks, Magumeri and Adamawa State recorded month; these included attacks Konduga LGAs recorded two on local communities, attacks on each while Jere, Mafa and an attack in Madagali highways in the state, suicide Maiduguri recorded several local government area bomb explosions, attacks with suicide bomb explosions. (LGA) while the remaining improvised explosive devices, Several military offensives nineteen attacks were in alleged abduction among others. against insurgents led to arrest, The number of attacks recorded destruction of logistical bases, Borno state; no insurgent in the month increased in release of captives and attack was recorded in comparison with the sixteen surrender of some Adamawa in February recorded in February 2017. insurgents.Other risk factors Map of Borno State (left) and Adamawa (right) showing incident spots 1 Risk I: Insurgent attacks on communities: Chart: Target/ victims of incident attacks Boko Haram and ISWAP members’ attacks on local communities accounted for about 30% of insurgent attacks recorded in the month The attack on Kumburu village in Madagali LGA of Adamawa state was the first attack recorded in the state since January 14 2017 At Kumburu, Boko Haram were dropped on a bush path by humanitarian crisis in the state members reportedly looted the the village. -

Monguno Bama Gwoza

DTM Flash Report Windstorm and rainfall damages to IDP sites Nigeria IOM DTM Rapid Assessment Monguno, Bama and Gwoza LGAs (Local Government Areas) 24 June 2021 SUMMARY PP PPPP 200 Households 671 Individuals 3 sites 130 Damaged shelters 11 Damaged toilets 8 Damaged shower points With the onset of the rainy season in Nigeria’s conflict-affected Kukawa Guzamala northeastern state of Borno, varying degrees of damages are expected to GGSS 431 Camp Gubio ± infrastructures (self-made and constructed) in camps and camp-like settings. Usually, heavy rainfalls are accompanied by strong winds Nganzai Monguno causing serious damage to shelters of IDPs. Marte Between 17 and 23 June 2021, IOM’s DTM programme carried out Ngala assessments to ascertain the level of damage sustained in camps and Magumeri camp-like settings due to heavy windstorms and rainfall. Overall, 2 Kala/Balge Mafa Jere camps and 1 collective settlement in the LGAs Monguno, Bama and Dikwa Gwoza LGAs were assessed. The worst-hit of the camps assessed was Maiduguri Goverment Girls Secondary School (GGSS) camp in Monguno LGA where a heavy rainfall damaged 33 shelters, affecting an estimated 431 GSSSS camp individuals. Konduga 225 Bama In total, 130 shelters were damaged by storms, leaving a total of 200 households without shelter. Additionally, a total of 11 toilets and 8 Gwoza showers were damaged by storms. There was no casualty as a result of 20 Housing XXX Affected population Damboa 15 Camp the storms. Per Location LGA Sources: Esri, HERE, Garmin, USGS, Intermap, INCREMENT P, NRCan, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China 0 5 10 20 30 40 Affected LGAs (Hong Kong), Esri Korea, Esri (Thailand), NGCC, (c) OpenStreetMap contributors, and the GIS User Miles Community, Esri, HERE, Garmin, (c) OpenStreetMap contributors, and the GIS user community The maps in this report are for illustra�on purposes only. -

Breaking Boko Haram and Ramping up Recovery: US-Lake Chad Region 2013-2016

From Pariah to Partner: The US Integrated Reform Mission in Burma, 2009 to 2015 Breaking Boko Haram and Ramping Up Recovery Making Peace Possible US Engagement in the Lake Chad Region 2301 Constitution Avenue NW 2013 to 2016 Washington, DC 20037 202.457.1700 Beth Ellen Cole, Alexa Courtney, www.USIP.org Making Peace Possible Erica Kaster, and Noah Sheinbaum @usip 2 Looking for Justice ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This case study is the product of an extensive nine- month study that included a detailed literature review, stakeholder consultations in and outside of government, workshops, and a senior validation session. The project team is humbled by the commitment and sacrifices made by the men and women who serve the United States and its interests at home and abroad in some of the most challenging environments imaginable, furthering the national security objectives discussed herein. This project owes a significant debt of gratitude to all those who contributed to the case study process by recommending literature, participating in workshops, sharing reflections in interviews, and offering feedback on drafts of this docu- ment. The stories and lessons described in this document are dedicated to them. Thank you to the leadership of the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) and its Center for Applied Conflict Transformation for supporting this study. Special thanks also to the US Agency for International Development (USAID) Office of Transition Initiatives (USAID/OTI) for assisting with the production of various maps and graphics within this report. Any errors or omis- sions are the responsibility of the authors alone. ABOUT THE AUTHORS This case study was produced by a team led by Beth ABOUT THE INSTITUTE Ellen Cole, special adviser for violent extremism, conflict, and fragility at USIP, with Alexa Courtney, Erica Kaster, The United States Institute of Peace is an independent, nonpartisan and Noah Sheinbaum of Frontier Design Group. -

Is There Borderline in Nigeria's Northeast? Multi-National Joint Task Force and Counterinsurgency Operation in Perspective

Vol. 14(2), pp. 33-45, April-June 2020 DOI: 10.5897/AJPSIR2019.1198 Article Number: 3CA422D63652 ISSN: 1996-0832 Copyright ©2020 African Journal of Political Science and Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJPSIR International Relations Full Length Research Paper Is there borderline in Nigeria's northeast? Multi-national joint task force and counterinsurgency operation in perspective Lanre Olu-Adeyemi* and Shaibu Makanjuola T. Department of Political Science and Administration, Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba, Ondo State, Nigeria. Received 10 September, 2019; Accepted 6 March, 2020 Borderline as a defence line is central in countering transnational insurgency. Yet, countries in African Sub-region are lackadaisical about redefining inherited colonial borders. Primarily, the study examined the origin of Multi-National Joint Task Force (MNJTF) counterinsurgency (COIN) operational mandate as well as the linkage between border, threat of insurgency and MNJTF COIN operation in Nigeria's northeastern region. It derived data from secondary sources and method of analysis adopted was content descriptive analysis; enemy-centric and population-centric COIN theories upheld this study. Interestingly, study reveals that in 1994, MNJTF was established by Nigeria to deal with insurgent from its northern borders and later expanded to include African neighbours. That in 2015, MNJTF was formally authorized under a new concept of operation to cover COIN with the mandate to: Create a safe environment in areas -

Living Through Nigeria's Six-Year

“When We Can’t See the Enemy, Civilians Become the Enemy” Living Through Nigeria’s Six-Year Insurgency About the Report This report explores the experiences of civilians and armed actors living through the conflict in northeastern Nigeria. The ultimate goal is to better understand the gaps in protection from all sides, how civilians perceive security actors, and what communities expect from those who are supposed to protect them from harm. With this understanding, we analyze the structural impediments to protecting civilians, and propose practical—and locally informed—solutions to improve civilian protection and response to the harm caused by all armed actors in this conflict. About Center for Civilians in Conflict Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC) works to improve protection for civil- ians caught in conflicts around the world. We call on and advise international organizations, governments, militaries, and armed non-state actors to adopt and implement policies to prevent civilian harm. When civilians are harmed we advocate the provision of amends and post-harm assistance. We bring the voices of civilians themselves to those making decisions affecting their lives. The organization was founded as Campaign for Innocent Victims in Conflict in 2003 by Marla Ruzicka, a courageous humanitarian killed by a suicide bomber in 2005 while advocating for Iraqi families. T +1 202 558 6958 E [email protected] www.civiliansinconflict.org © 2015 Center for Civilians in Conflict “When We Can’t See the Enemy, Civilians Become the Enemy” Living Through Nigeria’s Six-Year Insurgency This report was authored by Kyle Dietrich, Senior Program Manager for Africa and Peacekeeping at CIVIC. -

Tracking Displacement in the Lake Chad Basin

WITHIN AND BEYOND BORDERS: TRACKING DISPLACEMENT IN THE LAKE CHAD BASIN Regional Displacement and Human Mobility Analysis Displacement Tracking Matrix December 2016 INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION (IOM) DTM activities are supported by: Chad │Cameroon│Nigeria 1 The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community: to assist in meeting the growing operational challenges of migration management; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. PUBLISHER International Organization for Migration, Regional Office for West and Central Africa, Dakar, Senegal © 2016 International Organization for Migration (IOM) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. 2 IOM Regional Displacement Tracking Matrix INTRODUCTION Understanding and analysis of data, trends and patterns of human mobility is key to the provision of relevant and targeted humanitarian assistance. Humanitarian actors require information on the location and composition of the affected population in order to deliver services and respond to needs in a timely manner. -

ETT Report-No.32.V2

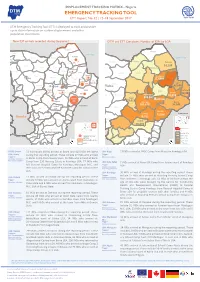

DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX - Nigeria DTM Nigeria EMERGENCY TRACKING TOOL ETT Report: No. 32 | 12–18 September 2017 IOM OIM DTM Emergency Tracking Tool (ETT) is deployed to track and provide up-to-date information on sudden displacement and other population movements New IDP arrivals recorded during the period DTM and ETT Cumulative Number of IDPs by LGA Abadam Abadam Yusufari Lake Chad Kukawa Yusufari Yunusari Mobbar Lake Chad± Nguru Karasuwa Niger Machina Yunusari Mobbar Abadam Kukawa Lake Chad Bade Guzamala 79 Nguru Karasuwa Kukawa Bursari 14,105 Geidam Gubio Bade Bade Guzamala Monguno Mobbar Nganzai Jakusko Bursari 6240 Marte Geidam Gubio Bade Guzamala Ngala Tarmua Monguno Magumeri Nganzai Jakusko Yobe 122,844 Marte 43 Gubio Monguno Jere Dikwa 7 Mafa Kala/BalgeYobe Ngala Maiduguri M.C. 122 Tarmua Nganzai Nangere Fune Damaturu Jigawa Magumeri 42,686 Borno 18 Yobe Marte Potiskum Ngala Kaga Konduga Bama Jere Mafa Kala/Balge Magumeri Dikwa 17 30 73 Yobe 49,480 Fika Gujba Nangere Fune Damaturu Maiduguri Mafa 74,858 Jere Dikwa Gwoza Potiskum Kaga Borno308,807 Kala-Balge MaiduBornoguri Damboa 799 19,619 KondugaKonduga Bama Gulani Cameroon Kag1a05,678 56,748 Chibok Konduga Fika Gujba Bama Biu 11 Madagali Askira/Uba Gwoza Michika Damboa Cameroon Kwaya Kusar 73,966Gwoza Hawul Damboa Bauchi Gombe Bayo Mubi North 76,795 Hong Gulani Shani Chibok Gombi Mubi South Madagali Biu Biu 16,378Chibok Maiha Askira/Uba Askira-Uba Inaccessible area Guyuk Song Michika Shelleng IDP severity Kwaya KusarKwaya Kusar Hawul Adamawa Hawul Less t han 10,788 Bauchi Gombe Bayo Mubi North Lamurde Number of new Bayo 10,788 - 25,813 HongAdamawa Numan Girei arrivals Shani Cameroon 25,813 - 56,749 Demsa Inaccessible area Shani Gombi Mubi South Yola South 56,749 - 122,770 Yola North Gombe 0 15 30 60 Km 122,770 Above Fufore LGAChad Adamawa Plateau Mayo-Belwa Shelleng Maiha Guyuk Song STATE: Borno 73 individuals (INDs) arrived at Bama and 129 INDs le� Bama LGA: Kaga 17 INDs arrived at NYSC Camp from Musari in Konduga LGA. -

Gwoza 1917 987 4239 Bama 2143 1026 5250 Mobbar 1212 411

IDPs DATA S.O.E STATES BORNO, YOBE AND ADAMAWA FROM JANUARY TO MARCH, 2014 TOTAL - 129,624 77,077 37,870 244,070 5,376 249,446 3,161,887 Number of IDPs living Number of Number Of Number of Number of with host IDPs in Total Number Total Affected STATE LGA Affected Children Women Men families Camps of IDPs Population Date of ocuranceNature of Disaster Borno GWOZA 1917 1335 987 4239 4,239 276,568 11/01/2014 INSURGENCY BAMA 2143 2081 1026 5250 5,250 270,119 13/01/2014 INSURGENCY MOBBAR 1212 727 411 2350 2,809 5,159 116,631 24/01/2014 INSURGENCY JERE 891 606 367 1864 1,864 209 24/01/2014 INSURGENCY DAMBOA 97 88 24 209 209 233,200 26/01/2014 INSURGENCY DAMBOA 118 113 38 269 567 836 836 26/01/2014 INSURGENCY DAMBOA 330 287 131 748 748 748 22/01/2014 INSURGENCY KONDUGA 1206 592 313 2111 2,111 157,322 02/02/2014 INSURGENCY BAMA 1511 1007 603 3121 3,121 3,121 05/02/2014 INSURGENCY GWOZA 1723 1215 805 3743 3,743 3,743 13/02/2014 INSURGENCY KONDUGA 2343 2099 1036 5478 5,478 5,478 14/02/2014 INSURGENCY DAMBOA 65 67 30 162 162 162 14/02/2014 INSURGENCY GWOZA 4403 2423 1309 8135 8,135 8,135 19/02/2014 INSURGENCY BAMA 2398 1804 911 5113 5,113 5,113 20/02/2014 INSURGENCY MMC 2289 1802 900 4991 4,991 4,991 01/03/2014 INSURGENCY KAGA 1201 582 303 2086 2,086 89,996 01/03/2014 INSURGENCY MAFA 2015 913 568 3496 3,496 3,496 02/03/2014 INSURGENCY KONDUGA 1428 838 513 2779 2,779 2,779 03/03/2014 INSURGENCY DAMBOA 2437 2055 1500 5992 5,992 5,992 04/03/2014 INSURGENCY DAMBOA 170 133 57 360 360 360 05/03/2014 INSURGENCY DAMBOA 406 343 211 960 960 960 06/03/2014 -

Boko Haram Stands at a Crossroads: Is the Era of Shekau Over ?

Boko Haram Stands at a Crossroads: Is the Era of Shekau Over ? Dr. David Doukhan May 2021 Boko Haram Stands at a Crossroads: Is the Era of Shekau Over? Since May 21st, 2021, all eyes have been focused on the elimination of Boko Haram’s leader Abu Baku Shekau. History shows us, that since 2009, Shekau has been allegedly killed four time on the battlefield. The last time, by the way, in 2016, he was only 'fatally wounded'. Each time, following his death announcement, like a phoenix in a well-prepared video, he reappears completely alive and well. In his speeches, he seems very comfortable, in full control and confidence, he speaks in the native Hausa language, spiced with verses from the Koran, in Arabic. Overall, he insists that he is alive and 'only by the will of God he will die' ([…] should know that he could not die except by the will of Allah […]). 1 Shekau is wanted by the United States (a bounty of $7 million was placed on his head).2 According to ISWAP (Islamic State of West Africa Province)3, Abu Bakar Shekau, Boko Haram’s leader, has barricaded himself with some of his followers and dozens of fighters in the thick forest of Sambisa. His hiding place was attacked by more than 30 armored vehicles carrying heavy weapons assisted by dozens of ISWAP fighters mounted on motorcycles. The attackers forced his fighters and bodyguards to surrender. According to their reports, Shekau chose to blow himself up rather than 1 About Shekau who died and was resurrected several times see the link: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-37476453 2 On June 21, 2012, the U.S. -

FEWS NET Special Report: a Famine Likely Occurred in Bama LGA and May Be Ongoing in Inaccessible Areas of Borno State

December 13, 2016 A Famine likely occurred in Bama LGA and may be ongoing in inaccessible areas of Borno State This report summarizes an IPC-compatible analysis of Local Government Areas (LGAs) and select IDP concentrations in Borno State, Nigeria. The conclusions of this report have been endorsed by the IPC’s Emergency Review Committee. This analysis follows a July 2016 multi-agency alert, which warned of Famine, and builds off of the October 2016 Cadre Harmonisé analysis, which concluded that additional, more detailed analysis of Borno was needed given the elevated risk of Famine. KEY MESSAGES A Famine likely occurred in Bama and Banki towns during 2016, and in surrounding rural areas where conditions are likely to have been similar, or worse. Although this conclusion cannot be fully verified, a preponderance of the available evidence, including a representative mortality survey, suggests that Famine (IPC Phase 5) occurred in Bama LGA during 2016, when the vast majority of the LGA’s remaining population was concentrated in Bama Town and Banki Town. Analysis indicates that at least 2,000 Famine-related deaths may have occurred in Bama LGA between January and September, many of them young children. Famine may have also occurred in other parts of Borno State that were inaccessible during 2016, but not enough data is available to make this determination. While assistance has improved conditions in accessible areas of Borno State, a Famine may be ongoing in inaccessible areas where conditions could be similar to those observed in Bama LGA earlier this year. Significant assistance in Bama Town (since July) and in Banki Town (since August/September) has contributed to a reduction in mortality and the prevalence of acute malnutrition, though these improvements are tenuous and depend on the continued delivery of assistance. -

GENDER ASSESSMENT January 2020

GENDER ASSESSMENT January 2020 Table of Contents List of graphs ....................................................................................................................................... ii List of table .......................................................................................................................................... ii Context .................................................................................................................................................... iii Objective .................................................................................................................................................. iii Methodology ........................................................................................................................................... iv Sampling .................................................................................................................................................. v Findings .................................................................................................................................................. vi Gender assessment analysis ................................................................................................................... 1 1. Socioeconomic activities and dynamics in the communities ........................................................ 2 1.1 Current daily activities of women compared to men ................................................................ 2 1.2 Type of livelihood