Attachment to Motion to Reinstate Third

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scholarships the Law School’S Lifeblood

SPRING 2004 Scholarships The Law School’s Lifeblood Thank You Donors 2004 SCHOLARSHIP RECIPIENTS DEAN Alex M. Johnson, Jr. EDITOR Terri Mische EDITORIAL ASSISTANCE Mickelene G.Taylor CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Mary Alton Marty Blake Dan Burk Cheryl Casey Bradley Clary Harriet Carlson Jonathan Eoloff Contents SPRING 2004 Amber Fox Susan Gainen 2 Burl Gilyard THE DEAN’S PERSPECTIVE Bobak Ha’Eri Katherine Hedin Betsy Hodges 3 FACULTY FOCUS Joan Howland Connie Lenz Faculty Research & Development Marty Martin Faculty Scholarship Meleah Maynard Todd Melby Kathryn Sedo Nick Spilman 18 FACULTY ESSAY Carl Warren Susan Wolf Light Thoughts and Night Thoughts Judith Younger on American Marriage PHOTOGRAPHERS Judith T.Yonger Bobak Ha’Eri Dan Kieffer Tim Rummelhoff 22 FEATURES Diane Walters Scholarships The Law School’s Lifeblood DESIGNER Todd Melby Jennifer Kaplan, Red Lime, LLC The Human Face of Legal Education The Law Alumni News magazine is published twice a year, by the Meleah Maynard University of Minnesota Law School Office of External Relations.The magazine is one of 32 the projects funded through the LAW SCHOOL NEWS membership dues of the Law Moot Court Teams Achieve Best Results in Alumni Association. History of Program Correspondence should be to: [email protected] or Law Law Library’s Millionth Volume Alumni News Editor, N160 Mondale Hall, 229 19th Avenue Second Annual Law School Musical South, Minneapolis, MN 55455-0400. 52 The University of Minnesota is ALUMNI COMMONS committed to the policy that all Distinguished Alumni persons shall have equal access to its programs, facilities and employ- Cover photo courtesy of Class Notes ment without regard to race, col- Dan Kieffer. -

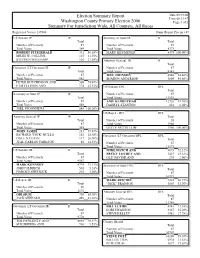

Gems Sovc Report

Election Summary Report Date:09/19/06 Time:08:21:47 Washington County Primary Election 2006 Page:1 of 2 Summary For Jurisdiction Wide, All Counters, All Races Registered Voters 139884 Num. Report Precinct 87 US Senator IP IP Secretary of State IR R Total Total Number of Precincts 87 Number of Precincts 87 Total Votes 584 Total Votes 8375 ROBERT FITZGERALD 331 56.68% MARY KIFFMEYER 8375 100.00% MILES W. COLLINS 127 21.75% STEPHEN WILLIAMS 126 21.58% Attorney General IR R Total Governor LT Governor IP IP Number of Precincts 87 Total Total Votes 8345 Number of Precincts 87 JEFF JOHNSON 4540 54.40% Total Votes 682 SHARON ANDERSON 3805 45.60% PETER HUTCHINSON AND 508 74.49% PAM ELLISON AND 174 25.51% US Senator DFL DFL Total Secretary of State IP IP Number of Precincts 87 Total Total Votes 13538 Number of Precincts 87 AMY KLOBUCHAR 12720 93.96% Total Votes 548 DARRYL STANTON 818 6.04% JOEL SPOONHEIM 548 100.00% US Rep 4 - DFL DFL Attorney General IP IP Total Total Number of Precincts 20 Number of Precincts 87 Total Votes 1960 Total Votes 585 BETTY MCCOLLUM 1960 100.00% JOHN JAMES 231 39.49% RICHARD "DICK" BULLO 152 25.98% Governor LT Governor DFL DFL DALE NATHAN 117 20.00% Total JUAL CARLOS CARLSON 85 14.53% Number of Precincts 87 Total Votes 13375 US Senator IR R MIKE HATCH AND 9673 72.32% Total BECKY LOUREY AND 3427 25.62% Number of Precincts 87 OLE' SAVIOR AND 275 2.06% Total Votes 9567 MARK KENNEDY 8774 91.71% Secretary of State DFL DFL JOHN ULDRICH 501 5.24% Total HAROLD SHUDLICK 292 3.05% Number of Precincts 87 Total Votes 10791 US Rep -

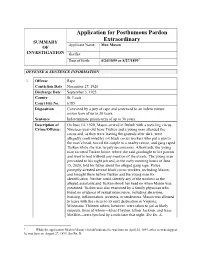

Application for Posthumous Pardon Extraordinary [Matter No

Application for Posthumous Pardon SUMMARY Extraordinary Applicant Name: Max Mason OF INVESTIGATION aka/fka: Date of Birth: 4/24/1899 or 8/27/18991 OFFENSE & SENTENCE INFORMATION 1. Offense Rape Conviction Date November 27, 1920 Discharge Date September 3, 1925 County St. Louis Court File No. 6785 Disposition Convicted by a jury of rape and sentenced to an indeterminate prison term of up to 30 years. Sentence Indeterminate prison term of up to 30 years. Description of On June 14, 1920, Mason arrived in Duluth with a traveling circus. Crime/Offense: Nineteen-year-old Irene Tusken and a young man attended the circus and, as they were leaving the grounds after dark, were allegedly confronted by six black circus workers who put a gun to the man’s head, forced the couple to a nearby ravine, and gang raped Tusken while she was largely unconscious. Afterwards, the young man escorted Tusken home, where she said goodnight to her parents and went to bed without any mention of the events. The young man proceeded to his night job and, in the early morning hours of June 15, 2020, told his father about the alleged gang rape. Police promptly arrested several black circus workers, including Mason, and brought them before Tusken and the young man for identification. Neither could identify any of the workers as the alleged assailants and Tusken shook her head no when Mason was presented. Tusken was also examined by a family physician who found no evidence of sexual intercourse, including abrasions, bruising, inflammation, soreness, or tenderness. Mason was allowed to leave with the circus to its next destination in Virginia, Minnesota. -

Eminent Domain Legislation Passes

EDITOR’S CORNER ■ Continued From Cover Bonding For A Better Minnesota candidates assured for all statewide positions. The But right now, the sun is shining, the grass is green, flowers Independence Party will hold its state convention on June are blooming and someplace in Minnesota a baseball game Marnie Moore 24, 2006. But just to keep it interesting, critical primaries is being played. Enjoy your summer!! apparently will be needed to determine the DFL candidate Published by the Government Relations Group END OF SESSION • 2006 After a promising start, a roller- with a vote of 111-21 in the House to the Perpich Center for Arts for governor and 5th District congressperson, respectively. If you would like to have your name added to the mailing coaster ride of contentious and 60-6 in the Senate. Although Education in Golden Valley. Attorney general Mike Hatch will be challenged by state list for future issues of CapitolWatch, please let us know. We conference committee meetings not everyone got what they wanted senator Becky Lourey for governor; state representative hope you enjoy this issue of CapitolWatch! Please contact us Eminent Domain Legislation Passes and final negotiations behind the this year, enough projects were If you love the outdoors, $100.7 Keith Ellison is being challenged by Paul Ostrow, Ember with any questions about topics discussed in this or future EDITOR’S CORNER Julie Perrus locked door of the governor’s funded to deem the bill an overall million was provided to preserve, Reichgott Junge and Mike Erlandson. These will be issues. We always welcome your feedback. -

State of Minnesota Office of the Attorney General

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp STATE OF MINNESOTA OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL ANNUAL REPORT REQUIRED BY Minnesota Statute Sections 8.08 and 8.15 Subdivision 4 (2017) Fiscal Year 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................... 1 CIVIL LITIGATION....................................................................................................... 2 REGULATORY LAW AND PROFESSIONS............................................................... 8 GOVERNMENT LEGAL SERVICES............................................................................ 14 STATE GOVERNMENT SERVICES............................................................................ 27 CIVIL LAW..................................................................................................................... 39 APPENDIX A: Recap of Legal Services........................................................................ A-1 APPENDIX B: Special Attorney Appointments............................................................ B-1 APPENDIX C: Attorney General Opinions oflnterest .................................................. C-1 INTRODUCTION This report is intended to fulfill the requirements of Minnesota Statutes Sections 8.08 and 8.15, Subdivision 4, for Fiscal Year 2018 (FY 2018). The Attorney General's Office (AGO) is organized -

State Executive Offices

Chapter Four State Executive Offices Governor .........................................................................................................282 Lieutenant Governor .......................................................................................283 Attorney General ............................................................................................284 State Auditor ...................................................................................................285 Secretary of State ............................................................................................286 Executive Councils and Boards .......................................................................288 Executive Officers Since Statehood ................................................................289 “The Moses who is leading Minnesota to the promised land.” Clara Ueland was a lifelong women’s rights activist and prominent Minnesotan suffragist. She was president of the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association when the nineteenth amendment was passed in 1919. That same year, she also became the first president of the Minnesota League of Women’s Voters. As women’s organizations gained momentum around the turn of the twentieth century, Ueland became serious about the suffrage movement. Her interest was piqued by a Minneapolis suffrage convention in 1901. Soon after, Ueland joined two organizations in support of the cause. She even went on to help found the Woman’s Club of Minneapolis, but left in 1912 to focus her energy on women’s voting -

State Court School Desegregation Cases: the New Frontier

State Court School Desegregation Cases: The New Frontier 2020 Edition LawPracticeCLE Unlimited All Courses. All Formats. All Year. ABOUT US LawPracticeCLE is a national continuing legal education company designed to provide education on current, trending issues in the legal world to judges, attorneys, paralegals, and other interested business professionals. New to the playing eld, LawPracticeCLE is a major contender with its oerings of Live Webinars, On-Demand Videos, and In-per- son Seminars. LawPracticeCLE believes in quality education, exceptional customer service, long-lasting relationships, and networking beyond the classroom. We cater to the needs of three divisions within the legal realm: pre-law and law students, paralegals and other support sta, and attorneys. WHY WORK WITH US? At LawPracticeCLE, we partner with experienced attorneys and legal professionals from all over the country to bring hot topics and current content that are relevant in legal practice. We are always looking to welcome dynamic and accomplished lawyers to share their knowledge! As a LawPracticeCLE speaker, you receive a variety of benets. In addition to CLE teaching credit attorneys earn for presenting, our presenters also receive complimentary tuition on LawPracticeCLE’s entire library of webinars and self-study courses. LawPracticeCLE also aords expert professors unparalleled exposure on a national stage in addition to being featured in our Speakers catalog with your name, headshot, biography, and link back to your personal website. Many of our courses accrue thousands of views, giving our speakers the chance to network with attorneys across the country. We also oer a host of ways for our team of speakers to promote their programs, including highlight clips, emails, and much more! If you are interested in teaching for LawPracticeCLE, we want to hear from you! Please email our Directior of Operations at [email protected] with your information. -

Spring 2001 LAW ALUMNI NEWS

cover S01a 3/29/01 5:39 PM Page 2 University of Minnesota Law School 229 19th Avenue South Nonprofit Org. Minneapolis, MN 55455 U.S. Postage PAID Minneapolis, MN Permit No. 155 cover S01a 3/29/01 5:39 PM Page 3 Spring 2001 LAW ALUMNI NEWS The Patriot, a 1984 acrylic by Carmen Cicero cover S01a 3/29/01 5:40 PM Page 4 LAW ALUMNI NEWS DEAN E. Thomas Sullivan EDITOR Terri Mische EDITORIAL ASSISTANCE ContentsSPRING 2001 G. Mickelene Garnett CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Susan Gainen Katherine Hedin Maury Landsman Martha Martin David Selden Linda Shimmin Amy Stine 22 Mary Thacker Tricia Baatz Torrey Carl Warren Janet Wigg Susan Wolf Cover photograph PHOTOGRAPHERS Through the generosity of West Group and its Dan Kieffer parent company Thomson Legal Publishing, the Tim Rummelhoff University of Minnesota Law School has acquired Diane Walters 34 the country’s finest collection of law-related contemporary American art. The Patriot, a 1984 DESIGNER acrylic by Carmen Cicero, is one of several pieces Features displayed in the Law School. Jennifer Kaplan Faculty Essay The Enduring Institution That is the Electoral College The Law Alumni News maga- By Dan Burk ..............................................................................................................................19 zine is published twice a year, in April and October, by the University of Minnesota Law Digital Legacies:The Arthur C. Pulling Rare Books Collection in Cyberspace School Office of Alumni Rela- By Katherine Hedin...................................................................................................................... tions and Communications. The 24 magazine is one of the projects funded through the member- Hands Across the Water, Hands Across the Sky:The Minnesota Connection ship dues of the Law Alumni Association. -

Chapter Four

State Executive Offices Chapter Four Chapter Four State Executive Offices Governor ...................................................................................................... 286 Lieutenant Governor .................................................................................... 287 Attorney General .......................................................................................... 288 State Auditor ................................................................................................ 289 Secretary of State ......................................................................................... 290 Executive Councils and Boards ................................................................... 292 Executive Officers Since Statehood ............................................................ 293 Image provided by the Minnesota Historical Society Governor William Marshall was Minnesota's fifth governor, serving from January 8, 1866 until January 9, 1870. He was instrumental in securing suffrage for African Americans in Minnesota in 1869. StateExecutive Offices Chapter Four Chapter Four State Executive Offices OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR Mark Dayton (Democratic-Farmer-Labor) Elected: 2010 Term: Four years Term expires: January 2015 Statutory Salary: $120,303 St. Paul. Blake School, Hopkins; BA, cum laude, Yale University (1969); Teacher, New York City Public Schools; Legislative Assistant, Senator Walter Mondale; Commissioner, Minnesota Department of Economic Development; Commissioner, Minnesota Department of -

Shifting Tides: Minnesota Tobacco Politics

UCSF Tobacco Control Policy Making: United States Title Shifting Tides: Minnesota Tobacco Politics Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1wh17656 Authors Tsoukalas, Theodore H., Ph.D. Ibrahim, Jennifer K., Ph.D. Glantz, Stanton A., Ph.D. Publication Date 2003-03-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Shifting Tides: Minnesota Tobacco Politics Theodore H. Tsoukalas Ph.D. Jennifer K. Ibrahim Ph.D. Stanton A. Glantz Ph.D. Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education Institute for Health Policy Studies School of Medicine University of California, San Francisco San Francisco CA 94118 March 2003 Shifting Tides: Minnesota Tobacco Politics Theodore H. Tsoukalas Ph.D. Jennifer K. Ibrahim Ph.D. Stanton A. Glantz Ph.D. Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education Institute for Health Policy Studies School of Medicine University of California, San Francisco San Francisco CA 94118 March 2003 Supported in part by National Cancer Institute Grant. Copyright 2003 by T.H. Tsoukalas, J.K. Ibrahim and S.A. Glantz. Permission is granted to reproduce this report for nonprofit purposes designed to promote the public health, so long as this report is credited. This report is available on the World Wide Web at http://repositories.cdlib.org/ctcre/tcpmus/MN2003/. This report is one of a series of reports that analyze tobacco industry campaign contributions, lobbying, and other political activity in California and other states. The other reports are available on the World Wide Web at http://repositories.cdlib.org/ctcre/. -

State Executive Offices Governor

Chapter Four State Executive Offices Governor .........................................................................................................282 Lieutenant Governor .......................................................................................283 Attorney General ............................................................................................284 State Auditor ...................................................................................................285 Secretary of State ............................................................................................286 Executive Councils and Boards .......................................................................288 Executive Officers Since Statehood ................................................................289 Voting Rights Act of 1965 - 50th Anniversary Civil rights activist Reverend James J. Reeb was killed during the civil rights marches in Selma, Alabama. He died on March 11, 1965. Rev. Reeb was a graduate of St. Olaf College in Minnesota. Following his death, St. Olaf announced a lecture series in his honor, as reported by the St. Paul Dispatch on March 16, 1965. St. Olaf ’s Announces Reeb Lecture Series Dispatch News Service NORTHFIELD—The president of St. Olaf college today announced the establishment of the James J. Reeb Memorial lecture series in honor of the clergyman killed in the cause of civil rights in Selma last week. President Sidney Rand made the announcement at a memorial service at 9 a.m. today in the college chapel. The -

STATE of MINNESOTA DISTRICT COURT COUNTY of RAMSEY SECOND JUDICIAL DISTRICT Dr. Jane Doe; Mary Moe; First Unitarian Society Of

62-CV-19-3868 Filed in District Court State of Minnesota 7/29/2020 6:03 PM STATE OF MINNESOTA DISTRICT COURT COUNTY OF RAMSEY SECOND JUDICIAL DISTRICT Dr. Jane Doe; Mary Moe; First Unitarian Case Type: Civil/Other Misc. Society of Minneapolis and Our Justice, Court File No: 62-CV-19-3868 Judge: Thomas Gilligan, Jr. Plaintiffs, vs. State of Minnesota, et al., NINETY-FIRST MINNESOTA STATE SENATE’S MEMORANDUM Defendants IN SUPPORT OF NOTICE OF INTERVENTION and Ninety-First Minnesota State Senate, [Proposed] Defendant- Intervenor. I. INTRODUCTION This lawsuit seeks to invalidate Minnesota statutes promoting quality health care and informed consent. The Ninety-First Minnesota State Senate (the “Senate”) is the only institution in Minnesota’s State Government that is able to defend the challenged statutes without conflict or qualification. The Court will depend on the adversarial presentation of argument and evidence to reach a just result. The Senate’s intervention will ensure that the Court, and the people of Minnesota, can be confident that this process will properly function in this suit. Observers of this litigation as diverse as Pro-Life Action Ministries and the New York Times, have raised material concerns regarding Attorney General Keith Ellison’s defense in this case. These concerns are the inevitable result of the Attorney General’s position in this suit. Mr. Ellison is required to defend statutes about which he has professed fundamental 62-CV-19-3868 Filed in District Court State of Minnesota 7/29/2020 6:03 PM disagreements, in a lawsuit brought by some of his closest political allies.