Handbook of Waterfowl Behavior, by Paul Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Endemic Ducks of Remote Islands DAVID LACK Introduction with the Names and Measurements of the Resident Forms of Anas

Ducks of remote islands 5 The endemic ducks of remote islands DAVID LACK Introduction with the names and measurements of the resident forms of Anas. On large islands This paper is concerned with all those and on islands near continents many ducks which have formed distinctive sub species of ducks coexist. For instance, 13 species restricted to one particular small species, 7 in the genus Anas, breed regu and remote island or archipelago. Only larly in Britain (Parslow 1967), 16 species, dabbling ducks in the genus Anas are 6 in the genus Anas, in Iceland (F. involved. Many species in this genus have Gudmundsson pers, com.), 8, 5 in the an extremely wide range, but the average genus Anas, in the Falkland Islands number of subspecies per species is as (Cawkell and Hamilton 1961) and 7, with low as 1.9 for the 38 species recognised 2 more in the nineteenth century, 4 in the by Delacour (1954-64). Hence the fact genus Anas, in New Zealand (Williams that nearly all the ducks on remote small 1964). Some of the Falklands and New islands are separate subspecies means that, Zealand forms are endemic, not so those for ducks, they belong to relatively of British or Iceland. Although the isolated populations. In contrast, on some various species of ducks look superficially of the archipelagos concerned, notably alike, especially when seen together in a the Hawaiian Islands and Galapagos, collection of living waterfowl, they have various of the land birds are distinctive in fact evolved an adaptive radiation species or even genera. -

Rockjumper Birding

Eastern South Africa & Cape Extension III Trip Report 29thJune to 17thJuly 2013 Orange-breasted Sunbird by Andrew Stainthorpe Trip report compiled by tour leader Andrew Stainthorpe Top Ten Birds seen on the tour as voted by participants: 1. Drakensberg Rockjumper 2. Orange-breasted Sunbird 3. Purple-crested Turaco 4. Cape Rockjumper 5. Blue Crane Trip Report - RBT SA Comp III June/July 2013 2 6. African Paradise Flycatcher 7. Long-crested Eagle 8. Klaas’s Cuckoo 9. Black Harrier 10. Malachite Sunbird. Eastern South Africa, with its diverse habitats and amazing landscapes, holds some truly breath-taking birds and game-rich reserves, and this was to be the main focus of our tour, with a short yet endemic-filled extension to the Western Cape. Commencing in busy Johannesburg, it was not long after we set off before we began ticking our first common birds for the tour, with an attractive pair of Red-headed Finches being a nice early bonus. Arriving at a productive small pan a while later, we found good numbers of water birds including Great Crested Grebe, African Swamphen, Cape Shoveler, Yellow-billed Duck, Greater Flamingo, Black-crowned Night Heron and Black-winged Stilt. We then made our way to the arid “thornveld” woodlands to the northeast of Pretoria and this certainly produced a good number of the more arid species right on their eastern limits of distribution. Some of the better birds seen in this habitat were the gaudy Crimson-breasted Shrike, Southern Pied Babbler, Black-faced Waxbill, Kalahari Scrub Robin, Chestnut-vented Warbler (Tit-babbler) and Greater Kestrel. -

Wild Patagonia & Central Chile

WILD PATAGONIA & CENTRAL CHILE: PUMAS, PENGUINS, CONDORS & MORE! NOVEMBER 1–18, 2019 Pumas simply rock! This year we enjoyed 9 different cats! Observing the antics of lovely Amber here and her impressive family of four cubs was certainly the highlight in Torres del Paine National Park — Photo: Andrew Whittaker LEADERS: ANDREW WHITTAKER & FERNANDO DIAZ LIST COMPILED BY: ANDREW WHITTAKER VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM Sensational, phenomenal, outstanding Chile—no superlatives can ever adequately describe the amazing wildlife spectacles we enjoyed on this year’s tour to this breathtaking and friendly country! Stupendous world-class scenery abounded with a non-stop array of exciting and easy birding, fantastic endemics, and super mega Patagonian specialties. Also, as I promised from day one, everyone fell in love with Chile’s incredible array of large and colorful tapaculos; we enjoyed stellar views of all of the country’s 8 known species. Always enigmatic and confiding, the cute Chucao Tapaculo is in the Top 5 — Photo: Andrew Whittaker However, the icing on the cake of our tour was not birds but our simply amazing Puma encounters. Yet again we had another series of truly fabulous moments, even beating our previous record of 8 Pumas on the last day when I encountered a further 2 young Pumas on our way out of the park, making it an incredible 9 different Pumas! Our Puma sightings take some beating, as they have stood for the last three years at 6, 7, and 8. For sure none of us will ever forget the magical 45 minutes spent observing Amber meeting up with her four 1- year-old cubs as they joyfully greeted her return. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Journal of Avian Biology 48:640-648

Journal of Avian Biology 48: 640–649, 2017 doi: 10.1111/jav.00998 © 2016 The Authors. Journal of Avian Biology © 2016 Nordic Society Oikos Subject Editor: Darren Irwin. Editor-in-Chief: Thomas Alerstam. Accepted 2 October 2016 Divergence and gene flow in the globally distributed blue-winged ducks Joel T. Nelson, Robert E. Wilson, Kevin G. McCracken, Graeme S. Cumming, Leo Joseph, Patrick-Jean Guay and Jeffrey L. Peters J. T. Nelson and J. L. Peters, Dept of Biological Sciences, Wright State Univ., Dayton, OH, USA. – R. E. Wilson ([email protected]), U. S. Geological Survey, Alaska Science Center, Anchorage, AK, USA. – K. G. McCracken and REW, Inst. of Arctic Biology, Dept of Biology and Wildlife, and Univ. of Alaska Museum, Univ. of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK, USA. KGM also at: Dept of Biology and Dept of Marine Biology and Ecology, Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, Univ. of Miami, Coral Gables, FL, USA. – G. S. Cumming, Percy FitzPatrick Inst., DST/NRF Centre of Excellence, Univ. of Cape Town, Rondebosch, South Africa, and ARC Centre of Excellence in Coral Reef Studies, James Cook Univ., Townsville, QLD, Australia. – L. Joseph, Australian National Wildlife Collection, National Research Collections Australia, CSIRO, Canberra, ACT, Australia. – P.-J. Guay, Inst. for Sustainability and Innovation, College of Engineering and Science, Victoria Univ., Melbourne, VIC, Australia. The ability to disperse over long distances can result in a high propensity for colonizing new geographic regions, including uninhabited continents, and lead to lineage diversification via allopatric speciation. However, high vagility can also result in gene flow between otherwise allopatric populations, and in some cases, parapatric or divergence-with-gene-flow models might be more applicable to widely distributed lineages. -

Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Sources Cited

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Sources Cited Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Sources Cited" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Sources Cited Alder, L. P. 1963. The calls and displays of African and In Bellrose, F. C. 1976. Ducks, geese and swans of North dian pygmy geese. In Wildfowl Trust, 14th Annual America. 2d ed. Harrisburg, Pa.: Stackpole. Report, pp. 174-75. Bellrose, F. c., & Hawkins, A. S. 1947. Duck weights in Il Ali, S. 1960. The pink-headed duck Rhodonessa caryo linois. Auk 64:422-30. phyllacea (Latham). Wildfowl Trust, 11th Annual Re Bengtson, S. A. 1966a. [Observation on the sexual be port, pp. 55-60. havior of the common scoter, Melanitta nigra, on the Ali, S., & Ripley, D. 1968. Handbook of the birds of India breeding grounds, with special reference to courting and Pakistan, together with those of Nepal, Sikkim, parties.] Var Fagelvarld 25:202-26. -

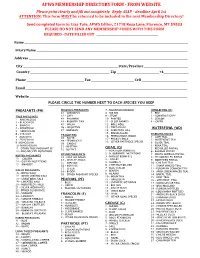

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - from WEBSITE Please Print Clearly and Fill out Completely

APWS MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - FROM WEBSITE Please print clearly and fill out completely. Reply ASAP – deadline April 1st ATTENTION: This form MUST be returned to be included in the next Membership Directory! Send completed form to: Lisa Tate, APWS Editor, 21718 Kesa Lane, Florence, MT 59833 PLEASE DO NOT SEND ANY MEMBERSHIP FUNDS WITH THIS FORM REQUIRED - DATE FILLED OUT ______________________________________________ Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Aviary Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Address _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ City ________________________________________________________________________ State/Province _________________________________ Country ___________________________________________________________ Zip ________________________________+4___________________ Phone ___________________________________________ Fax ________________________________ Cell __________________________________ Email _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Website ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PLEASE CIRCLE THE NUMBER NEXT TO EACH SPECIES YOU KEEP PHEASANTS (PH) PEACOCK-PHEASANTS 7 - MOUNTAIN BAMBOO JUNGLEFOWL -

Wetlands Australia

Wetlands Australia National wetlands update August 2014—Issue No 25 Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment. © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2014 Wetlands Australia National Wetlands Update August 2014 – Issue No 25 is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons By Attribution 3.0 Australia licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au This report should be attributed as ‘Wetlands Australia National Wetlands Update August 2015 – Issue No 25, Commonwealth of Australia 2014’ The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Cover images Front cover: Wetlands provide important habitats for waterbirds, such as this adult great egret (Ardea modesta) at Leichhardt Lagoon in Queensland (© Copyright, Brian Furby) Back cover: Inland wetlands, like Narran Lakes Nature Reserve Ramsar site in New South Wales, support high numbers of waterbird breeding and provide refuge for birds during droughts (© Copyright, Dragi Markovic) ii / Wetlands Australia August 2014 Contents Introduction to Wetlands Australia August -

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island Operated by Chevron Australia This document has been printed by a Sustainable Green Printer on stock that is certified carbon in joint venture with neutral and is Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) mix certified, ensuring fibres are sourced from certified and well managed forests. The stock 55% recycled (30% pre consumer, 25% post- Cert no. L2/0011.2010 consumer) and has an ISO 14001 Environmental Certification. ISBN 978-0-9871120-1-9 Gorgon Project Osaka Gas | Tokyo Gas | Chubu Electric Power Chevron’s Policy on Working in Sensitive Areas Protecting the safety and health of people and the environment is a Chevron core value. About the Authors Therefore, we: • Strive to design our facilities and conduct our operations to avoid adverse impacts to human health and to operate in an environmentally sound, reliable and Dr Dorian Moro efficient manner. • Conduct our operations responsibly in all areas, including environments with sensitive Dorian Moro works for Chevron Australia as the Terrestrial Ecologist biological characteristics. in the Australasia Strategic Business Unit. His Bachelor of Science Chevron strives to avoid or reduce significant risks and impacts our projects and (Hons) studies at La Trobe University (Victoria), focused on small operations may pose to sensitive species, habitats and ecosystems. This means that we: mammal communities in coastal areas of Victoria. His PhD (University • Integrate biodiversity into our business decision-making and management through our of Western Australia) -

Bird Vulnerability Assessments

Assessing the vulnerability of native vertebrate fauna under climate change, to inform wetland and floodplain management of the River Murray in South Australia: Bird Vulnerability Assessments Attachment (2) to the Final Report June 2011 Citation: Gonzalez, D., Scott, A. & Miles, M. (2011) Bird vulnerability assessments- Attachment (2) to ‘Assessing the vulnerability of native vertebrate fauna under climate change to inform wetland and floodplain management of the River Murray in South Australia’. Report prepared for the South Australian Murray-Darling Basin Natural Resources Management Board. For further information please contact: Department of Environment and Natural Resources Phone Information Line (08) 8204 1910, or see SA White Pages for your local Department of Environment and Natural Resources office. Online information available at: http://www.environment.sa.gov.au Permissive Licence © State of South Australia through the Department of Environment and Natural Resources. You may copy, distribute, display, download and otherwise freely deal with this publication for any purpose subject to the conditions that you (1) attribute the Department as the copyright owner of this publication and that (2) you obtain the prior written consent of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources if you wish to modify the work or offer the publication for sale or otherwise use it or any part of it for a commercial purpose. Written requests for permission should be addressed to: Design and Production Manager Department of Environment and Natural Resources GPO Box 1047 Adelaide SA 5001 Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources makes no representations and accepts no responsibility for the accuracy, completeness or fitness for any particular purpose of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of or reliance on the contents of this publication. -

A Year on the Vasse-Wonnerup Wetlands

Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development Department of Water and Environmental Regulation A Year on the Vasse-Wonnerup Wetlands An Ecological Snapshot March 2017—January 2018 W IN N T M E U R T U A S P R R I N E G M M U S Musk duck (Biziura lobata) (Photo: Mark Oliver) The Vasse-Wonnerup Wetlands The conservation values of the Vasse-Wonnerup wetlands are recognised on a local, state, national and international level. The wetlands provide habitat to thousands of Australian and migratory water birds as well as supporting the largest breeding population of black swans in the state. In 1990 the wetlands were recognised as a ‘Wetland of International Importance’ under the Ramsar Convention. The wetlands are also one of the most nutrient enriched wetlands in Western Australia, characterised by extensive macroalgae and phytoplankton blooms and occasional major fish kills. Poor water quality in the wetlands is a major concern for the local community. Over the past four years scientists have been working together to investigate options to improve water quality in the wetlands by monitoring seawater inflows through the Vasse surge barrier and modelling options to increase water levels and flows into the Vasse estuary. These trials have successfully shown that seawater inflows can reduce the incidence of harmful phytoplankton blooms and improve conditions for fish in the Vasse Estuary Channel over summer months. What isn’t as well understood is how these management approaches and subsequent increased water levels may impact on the broader wetland system, especially how the ecology of the wetlands responds to changes in the timing and volume of seawater inflow through the surge barriers. -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible.