A Century of the Philippine Labor Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: WAR AND RESISTANCE: THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida, History Department What happened in the Philippine Islands between the surrender of Allied forces in May 1942 and MacArthur’s return in October 1944? Existing historiography is fragmentary and incomplete. Memoirs suffer from limited points of view and personal biases. No academic study has examined the Filipino resistance with a critical and interdisciplinary approach. No comprehensive narrative has yet captured the fighting by 260,000 guerrillas in 277 units across the archipelago. This dissertation begins with the political, economic, social and cultural history of Philippine guerrilla warfare. The diverse Islands connected only through kinship networks. The Americans reluctantly held the Islands against rising Japanese imperial interests and Filipino desires for independence and social justice. World War II revealed the inadequacy of MacArthur’s plans to defend the Islands. The General tepidly prepared for guerrilla operations while Filipinos spontaneously rose in armed resistance. After his departure, the chaotic mix of guerrilla groups were left on their own to battle the Japanese and each other. While guerrilla leaders vied for local power, several obtained radios to contact MacArthur and his headquarters sent submarine-delivered agents with supplies and radios that tie these groups into a united framework. MacArthur’s promise to return kept the resistance alive and dependent on the United States. The repercussions for social revolution would be fatal but the Filipinos’ shared sacrifice revitalized national consciousness and created a sense of deserved nationhood. The guerrillas played a key role in enabling MacArthur’s return. -

Reflections on Agoncilloʼs the Revolt of the Masses and the Politics of History

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 49, No. 3, December 2011 Reflections on Agoncilloʼs The Revolt of the Masses and the Politics of History Reynaldo C. ILETO* Abstract Teodoro Agoncilloʼs classic work on Andres Bonifacio and the Katipunan revolt of 1896 is framed by the tumultuous events of the 1940s such as the Japanese occupation, nominal independence in 1943, Liberation, independence from the United States, and the onset of the Cold War. Was independence in 1946 really a culmination of the revolution of 1896? Was the revolution spearheaded by the Communist-led Huk movement legitimate? Agoncilloʼs book was written in 1947 in order to hook the present onto the past. The 1890s themes of exploitation and betrayal by the propertied class, the rise of a plebeian leader, and the revolt of the masses against Spain, are implicitly being played out in the late 1940s. The politics of hooking the present onto past events and heroic figures led to the prize-winning manuscriptʼs suppression from 1948 to 1955. Finally seeing print in 1956, it provided a novel and timely reading of Bonifacio at a time when Rizalʼs legacy was being debated in the Senate and as the Church hierarchy, priests, intellectuals, students, and even general public were getting caught up in heated controversies over national heroes. The circumstances of how Agoncilloʼs work came to the attention of the author in the 1960s are also discussed. Keywords: Philippine Revolution, Andres Bonifacio, Katipunan society, Cold War, Japanese occupation, Huk rebellion, Teodoro Agoncillo, Oliver Wolters Teodoro Agoncilloʼs The Revolt of the Masses: The Story of Bonifacio and the Katipunan is one of the most influential books on Philippine history. -

Abdullah Ahmad Badawi 158 Abidjan 14, 251, 253-5, 257, 261, 274

Index Abdullah Ahmad Badawi 158 Association of Southeast Asian Nations Abidjan 14, 251, 253-5, 257, 261, 274-6, (ASEAN) 161 281, 283 Aung San 149 Abuja 249 Australia 30, 70 Accra 241 Ayal, Eliezer 82, 91-2 Aceh 70-1, 137, 140-2, 144, 146, 151-3, 162 Badan Pertanahan Nasional 226 Achebe, Chinua 8, 9, 25 Balante 179 African National Congress 255 Bali 148, 153 Aguinaldo, Emilio 168 Balkans 153 Aguman ding Malding Talapagobra Bamako 276 (General Workers Union) 173-4 Bandung 228 Ahonsi, Babatunde 250 Bangkok 72-3 Alatas, Syed Hussein 76 Bankimchandra 191 Albay 171 Bank Negara Indonesia 128 Albertini, Rudolf von 27 Bankoff, Greg 3 Alexander, Jennifer 84 Bank (of) Indonesia 127-30 Alexander, Paul 84 Banten 70-1 Algeria 27, 32, 41-4, 48, 59, 61, 242, 244-7 Barisan Nasional 154-5, 157-9 Algiers 32, 242, 246-7 Barisan Sosialis 159 Ali Wardhana 129 Batavia 32, 71-2, 125, 228, 230 All Burma Volunteers 144 Bédié, Henri Konan 253 Alliance (Malaya) 94, 154-5, 157, 159 Bedner, Adriaan 226 Ambon, Ambonese 143, 148, 227 Beijing 157 American see United States Belgium 40, 116, 242, 247, 271 Amin, Samir 29 Ben Bella, Ahmed 246 Amsterdam 27 Bengal, Bengali 9, 191-2, 196-7 Anderson, Benedict 13 Bénin 252, 276 Angola 243 Benteng programme 93, 97 Ang Uliran 178 Beti, Mongo 12 Annam 81 Betts, Raymond 2 Anspach, Ralph 93, 109, 125 Bobo-Dioulassou 276 Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League Boeke, J.H. 75-6, 83 149 Bogaerts, Els 2 Anwar Ibrahim 158 Bollywood 206 Aquino, Cory 100 Bombay 14, 32, 198-203, 205-6 Arab 71, 246 Bombay Municipal Corporation 200 Arabic 10, 140 Bonifacio, Andres 168 Araneta, Salvador 119 Booth, Anne 3 Ardener, Shirley 169 Borneo see Kalimantan Arusha 281 Botha, Louis 35 Ashcroft, Bill 30 Botswana 254 Ashley, S.D. -

A Century of Struggle

A Century of Struggle To mark the 100th anniversary of the formation of the American Federation of Labor, the National Museum of American History of the Smithsonian Institution invited a group of scholars and practitioners "to examine the work, technology, and culture of industrial America . " The conference was produced in cooperation with the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations . The excerpts on the following pages are drawn from papers and comments at that conference, in the Museum's Carmichael Auditorium, November IS and 16, 1986. Mary Kay Rieg, Olivia G. Amiss, and Marsha Domzalski of the Monthly Labor Review provided editorial assistance. Trade unions mirror society in conflict between collectivism and individualism A duality common to many institutions runs through the American labor movement and has marked its shifting fortunes from the post-Civil War period to the present ALICE KESSLER-HARRIS ideology of American trade unions as they developed in Two competing ideas run through the labor movement, as and post-Civil War period. It also tells us something of their they have run through the American past. The first is the the The conglomeration of unions that formed the Na- notion of community-the sense that liberty is nurtured in impact . Union and the 15,000 assemblies of the an informal political environment where the voluntary and tional Labor of Labor responded to the onslaught of industrial- collective enterprise of people with common interests con- Knights the Civil War by searching for ways to reestablish tributes to the solution of problems . Best characterized by ism after of interest that was threatened by a new and the town meeting, collective solutions are echoed in the the community organization of work. -

Apolinario Mabini, Isabelo De Los Reyes, and the Emergence of a “Public” 1 Resil B

Apolinario Mabini, Isabelo de los Reyes, and the Emergence of a “Public” 1 Resil B. Mojares Abstract The paper sketches the factors behind the emergence of a “public” in the late nineteenth century, and locates in this context the distinctive careers of Apolinario Mabini and Isabelo de los Reyes. The activities of Mabini and de los Reyes were enabled by the emergence of a “public sphere” in the colony, at the same time that their activities helped define and widen a sphere that had become more distinctly ‘national’ in character. Complicating the Habermasian characterization of a “bourgeois public sphere,” the paper calls for a fuller study of the more popular agencies, sites, media, and networks in the formation of a public in nineteenth-century Philippines. Plaridel • Vol. 13 No. 1 • 2016 1 - 15 THEY are an odd couple. They were born in the same month and year (July 1864), studied for the same profession in the same university, and participated in the biggest event of their time, the anti-colonial struggle for independence. Yet, it seems that they never met. They were contrasting personalities, to begin with: on one hand, an Ilocano of the landed gentry in Vigan, energetic, individualistic, confident and reckless; on the other hand, the son of poor peasants in Batangas, paralytic, very private, and highly principled, almost puritanical. If there is one quick lesson to be drawn from these contrasts, it is this: the struggle for independence was a complex, volatile event that encompassed divergent personalities and diverse forms of action, played out in social space that was heterogeneous and dynamic. -

1930-1957 the Communist Party of China and The

1930-1957 THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF CHINA AND THE EARLY PHILIPPINE SOCIALIST MOVEMENT (1930-1957) YANG JINGLIN 530008 (Guangxi University for Nationalities, Nanning , Guangxi 530008) [email protected] Received: 12 April 2020 / Revised: 11 June 2020 / Accepted: 17 June 2020 ABSTRACT During the American colonial rule, The movement of workers and peasants in the Philippines developed to a large extent. With the help of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), a group of Filipino worker’s leaders, Who had received the ideological edification of Marxism-Leninism, founded the Communist Party of the Philippines(CPP) in 1930which was organized by the left forces and formulated the -20-0(006)069-080.indd 69 13/7/2563 BE 13:13 revolutionary program as well as launched the early Socialist Movement obviously influenced by China’s revolution. CPP sought for the cooperation with CCP to fight against Japanese aggression, and then Mao Zedong’s revolutionary ideas were spread among the Filipino communist in the period of World War Two. Due to undergoing the armed resistance for Japan’s invasion, the socialist forces of the Philippines has grew and expanded. They learned from the model of CCP, setting up the communist-controlled base area and the people’s democratic government. After war, Philippines socialist movement abandoned the guerrilla warfare advocated by CCP and disbanded the armed forces, even took the strategy of parliamentary elections to take control the country. However, the military encirclement and suppression of United States arm jointing Philippines governments and the failed strategy from the leaders of PCP led to the consequence of the setback of Philippine communism activism. -

4Th Ed (1932) 32Pp

WORKERS DEMONSTRATE, UNION SQUARE, NEW YORK, MAY DAY, 1930 loaf bread business have for years been suffering worse than Egyp tian bondage. They have had to labor on an average of eighteen to twenty hours out of the twenty-four." The demand in those localities for a Io-hour day soon grew into a movement, which, although impeded by the crisis of 1837, led the federal government under President Van Buren to decree the Io-hour day for all those employed on government work. The struggle for the universality of the Io-hour day, however, continued during the next decades. No sooner had this demand been secured in a number of industries than the workers began to raise the slogan for an 8-hour day. The feverish activity in organizing lab()r unions during the fifties gave this nltw demand an impetus which, however, was checked by the crisis of 1857. The demand was, however, won in a few well-organized trades before the crisis. That the movement for a shorter workday was not only peculiar to the United States, but was prevalent wher ever workers were exploited under the rising capitalist system, can be seen from the fact that even in far away Australia the building trade workers raised the slogan "8 hours work, 8 hours recreation and 8 hours rest" and were successful in securing this demand in 1856. Eight-Hour Movement Started in America The 8-hour day movement which directly gave birth to May Day, must, however, be traced to the general movement initiated in the United States in 1884. -

Bayan Muna – Security Forces – State Protection

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: PHL32251 Country: Philippines Date: 27 September 2007 Keywords: Philippines – Bayan Muna – Security forces – State protection This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide a brief overview of the political platform of the Bayan Muna party. 2. Please provide information on whether Bayan Muna members have been targeted by the authorities or other groups. Are there reports of campaigners being targeted? Or is the mistreatment restricted to leaders and electoral candidates? 3. Please provide information on whether the state has provided protection to Bayan Muna members. Have episodes of mistreatment been investigated and prosecuted? RESPONSE 1. Please provide a brief overview of the political platform of the Bayan Muna party. Bayan Muna (People First) is a legally registered left-wing1 progressive party-list group. The party currently has three representatives in Congress. According to the Bayan Muna website, the party “stand[s] on a platform of change and social transformation that addresses the basic problems that have plagued our country – foreign domination, feudal bondage and a graft- ridden government”. Bayan Muna is ideologically close to the Communist Party (CPP) and, along with other left-wing parties, is often accused by the military of being a front for the CPP’s underground organisations and the New People’s Army (NPA) (‘Commitment and 1 In the Philippines, the terms “the left” or “leftists” encompass a broad range of political meaning. -

Singsing- Memorable-Kapampangans

1 Kapampangan poet Amado Gigante (seated) gets his gold laurel crown as the latest poet laureate of Pampanga; Dhong Turla (right), president of the Aguman Buklud Kapampangan delivers his exhortation to fellow poets of November. Museum curator Alex Castro PIESTANG TUGAK NEWSBRIEFS explained that early Kapampangans had their wakes, funeral processions and burials The City of San Fernando recently held at POETS’ SOCIETY photographed to record their departed loved the Hilaga (former Paskuhan Village) the The Aguman Buklud Kapampangan ones’ final moments with them. These first-of-its-kind frog festival celebrating celebrated its 15th anniversary last pictures, in turn, reveal a lot about our Kapampangans’ penchant for amphibian November 28 by holding a cultural show at ancestors’ way of life and belief systems. cuisine. The activity was organized by city Holy Angel University. Dhong Turla, Phol tourism officer Ivan Anthony Henares. Batac, Felix Garcia, Jaspe Dula, Totoy MALAYA LOLAS DOCU The Center participated by giving a lecture Bato, Renie Salor and other officers and on Kapampangan culture and history and members of the organization took turns lending cultural performers like rondalla, reciting poems and singing traditional The Center for Kapampangan Studies, the choir and marching band. Kapampangan songs. Highlight of the show women’s organization KAISA-KA, and was the crowning of laurel leaves on two Infomax Cable TV will co-sponsor the VIRGEN DE LOS new poets laureate, Amado Gigante of production of a video documentary on the REMEDIOS POSTAL Angeles City and Francisco Guinto of plight of the Malaya Lolas of Mapaniqui, Macabebe. Angeles City Councilor Vicky Candaba, victims of mass rape during World COVER Vega Cabigting, faculty and students War II. -

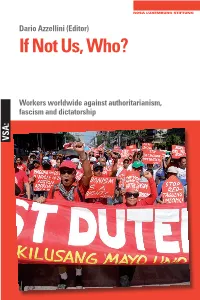

If Not Us, Who?

Dario Azzellini (Editor) If Not Us, Who? Workers worldwide against authoritarianism, fascism and dictatorship VSA: Dario Azzellini (ed.) If Not Us, Who? Global workers against authoritarianism, fascism, and dictatorships The Editor Dario Azzellini is Professor of Development Studies at the Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas in Mexico, and visiting scholar at Cornell University in the USA. He has conducted research into social transformation processes for more than 25 years. His primary research interests are industrial sociol- ogy and the sociology of labour, local and workers’ self-management, and so- cial movements and protest, with a focus on South America and Europe. He has published more than 20 books, 11 films, and a multitude of academic ar- ticles, many of which have been translated into a variety of languages. Among them are Vom Protest zum sozialen Prozess: Betriebsbesetzungen und Arbei ten in Selbstverwaltung (VSA 2018) and The Class Strikes Back: SelfOrganised Workers’ Struggles in the TwentyFirst Century (Haymarket 2019). Further in- formation can be found at www.azzellini.net. Dario Azzellini (ed.) If Not Us, Who? Global workers against authoritarianism, fascism, and dictatorships A publication by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung VSA: Verlag Hamburg www.vsa-verlag.de www.rosalux.de This publication was financially supported by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung with funds from the Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) of the Federal Republic of Germany. The publishers are solely respon- sible for the content of this publication; the opinions presented here do not reflect the position of the funders. Translations into English: Adrian Wilding (chapter 2) Translations by Gegensatz Translation Collective: Markus Fiebig (chapter 30), Louise Pain (chapter 1/4/21/28/29, CVs, cover text) Translation copy editing: Marty Hiatt English copy editing: Marty Hiatt Proofreading and editing: Dario Azzellini This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution–Non- Commercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Germany License. -

Histories of Racial Capitalism

HISTORIES OF RACIAL CAPITALISM COLUMBIA STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF U.S. CAPITALISM COLUMBIA STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF U.S. CAPITALISM Series Editors: Devin Fergus, Louis Hyman, Bethany Moreton, and Julia Ott Capitalism has served as an engine of growth, a source of inequality, and a catalyst for conflict in American history. While remaking our material world, capitalism’s myriad forms have altered—and been shaped by—our most fundamental experiences of race, gender, sexuality, nation, and citizenship. This series takes the full measure of the complexity and significance of capitalism, placing it squarely back at the center of the American experience. By drawing insight and inspiration from a range of disciplines and alloying novel methods of social and cultural analysis with the traditions of labor and business history, our authors take history “from the bottom up” all the way to the top. Capital of Capital: Money, Banking, and Power in New York City, 1784–2012, by Steven H. Jaffe and Jessica Lautin From Head Shops to Whole Foods: The Rise and Fall of Activist Entrepreneurs, by Joshua Clark Davis Creditworthy: A History of Consumer Surveillance and Financial Identity in America, by Josh Lauer American Capitalism: New Histories, edited by Sven Beckert and Christine Desan Buying Gay: How Physique Entrepreneurs Sparked a Movement, by David K. Johnson City of Workers, City of Struggle: How Labor Movements Changed New York, edited by Joshua B. Freeman Banking on Freedom: Black Women in U.S. Finance Before the New Deal, by Shennette Garrett-Scott Threatening Property: Race, Class, and Campaigns to Legislate Jim Crow Neighborhoods, by Elizabeth A. -

Volume II, Number 16. 15 August 2020

UPDATES PHILIPPINES Released by the National Democratic Front of the Philippines Amsterdamsestraatweg 50, 3513AG Utrecht, The Netherlands T: : +31 30 2310431 | E: [email protected] | W: updates.ndfp.org vol iI no 16 15 AUGUST 2020 EDITORIAL Respect the dead, friend or foe It is a tradition in most cultures in the world to respect the dead, whether the deceased was a friend, a foe or an unknown. This culture of respect is even more ingrained among the Filipino people who honor, nay, even venerate, their departed. More so, many even extend the period of mourning up to forty days after the demise of their loved one. Thus, it was a shock to the people that Ka Randall Echanis, a respected champion for genuine land reform and a major consultant of the NDFP peace panel for social and economic reforms, was brutally murdered before dawn of August 10 by suspected state agents. Adding anger to the shock, on the evening of the same day, Ka Randy’s mutilated body was forcibly taken by the police from his widow, family and friends. The obvious aim for the abduction was to obliterate marks of torture from his body. This is in fact not the first time that armed minions of the regime maltreated the remains of their victims. After an armed encounter in Laguna province last 5 August, the police took the remains of three NPA members from a funeral home to their base, Camp Vicente Lim, without the knowledge much less the permission of the victims’ relatives. The three NPA victims and two more are still held in the base as of this writing.