Copyright by Beatrice Giuseppina Mabrey 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

It 2.007 Vc Italian Films On

1 UW-Madison Learning Support Services Van Hise Hall - Room 274 rev. May 3, 2019 SET CALL NUMBER: IT 2.007 VC ITALIAN FILMS ON VIDEO, (Various distributors, 1986-1989) TYPE OF PROGRAM: Italian culture and civilization; Films DESCRIPTION: A series of classic Italian films either produced in Italy, directed by Italian directors, or on Italian subjects. Most are subtitled in English. Individual times are given for each videocassette. VIDEOTAPES ARE FOR RESERVE USE IN THE MEDIA LIBRARY ONLY -- Instructors may check them out for up to 24 hours for previewing purposes or to show them in class. See the Media Catalog for film series in other languages. AUDIENCE: Students of Italian, Italian literature, Italian film FORMAT: VHS; NTSC; DVD CONTENTS CALL NUMBER Il 7 e l’8 IT2.007.151 Italy. 90 min. DVD, requires region free player. In Italian. Ficarra & Picone. 8 1/2 IT2.007.013 1963. Italian with English subtitles. 138 min. B/W. VHS or DVD.Directed by Frederico Fellini, with Marcello Mastroianni. Fellini's semi- autobiographical masterpiece. Portrayal of a film director during the course of making a film and finding himself trapped by his fears and insecurities. 1900 (Novocento) IT2.007.131 1977. Italy. DVD. In Italian w/English subtitles. 315 min. Directed by Bernardo Bertolucci. With Robert De niro, Gerard Depardieu, Burt Lancaster and Donald Sutherland. Epic about friendship and war in Italy. Accattone IT2.007.053 Italy. 1961. Italian with English subtitles. 100 min. B/W. VHS or DVD. Directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini. Pasolini's first feature film. In the slums of Rome, Accattone "The Sponger" lives off the earnings of a prostitute. -

Comunicato Stampa 01 Il Premio Gian Maria Volonté 2018 a Isabella

Comunicato stampa 01 Il Premio Gian Maria Volonté 2018 a Isabella Ragonese La Maddalena, 14 giugno 2018 Durante la quindicesima edizione del festival La Valigia dell’Attore, manifestazione organizzata dall’Associazione culturale Quasar diretta da Giovanna Gravina Volonté e da Fabio Canu, in programma nell’isola di La Maddalena dal 24 al 29 luglio, sarà consegnato dal circuito “Le isole del cinema”, il Premio Gian Maria Volonté 2018 all’eccellenza artistica. A riceverlo, la sera del 25 luglio sul palco della fortezza I Colmi, l’attrice e autrice Isabella Ragonese. Il suo esordio nel cinema nel 2006 con Nuovomondo di Emanuele Crialese; è poi la protagonista del film di Paolo Virzì Tutta la vita davanti che le vale la candidatura al Nastro d'Argento come migliore attrice protagonista. Recita poi in Viola di mare di Donatella Maiorca, Due vite per caso di Alessandro Aronadio, Oggi sposi di Luca Lucini, Dieci inverni di Valerio Mieli, Un altro mondo di Silvio Muccino. Nel 2010, con il film La nostra vita di Daniele Luchetti vince il Nastro d'Argento come migliore attrice non protagonista. Nello stesso anno recita per la prima volta in una produzione televisiva, lavorando in uno dei film de Il commissario Montalbano, ed è inoltre madrina della 67esima Mostra Internazionale d'Arte Cinematografica di Venezia, dove viene presentato il film Il primo incarico, della regista Giorgia Cecere, di cui è protagonista. Nel 2011 è in teatro con il monologo “Lady Grey” di Will Eno. È ancora la protagonista del film di Fabio Volo Il giorno in più e nel 2012 è stata insignita al Festival di Berlino del premio “Shooting Star” come miglior talento europeo dell’anno. -

Table Des Matières

Table des matières Préface 5 L’importance de l’archive dans la littérature de la postmodernité Margherita Ganeri «Il ritorno alla realtà» nel romanzo degli anni zero 11 Jean-François Carcelén Écriture de l’Histoire et postmodernité Le roman espagnol actuel et la mémoire revisitée 21 Ana Paula Arnaut La reescritura del pasado en clave postmodernista 31 Walter Geerts Le roman historique et ses messies À propos de Perec, Goytísolo, Tournier, Lobo Antunes et Saramago 45 Catherine De Wrangel-Lanfranchi Écriture et Histoire dans le roman historique postmoderne en France et en Italie. Peut-on parler de la constitution d’un modèle national ? 55 Alessandro Leiduan La réécriture postmoderne de l’Histoire ou le crépuscule de la praxis 67 Giuseppe Lovito La construction du sens de l’Histoire dans Le Pendule de Foucault et dans Baudolino d’Umberto Eco 79 Réflexions sur la réinvention de l’Histoire Claudio Milanesi 91 Il complotto, il gioco, la realtà Umberto Eco, George Orwell, Primo Levi, Dan Brown… 91 Leonardo Manigrasso Le eterne passioni degli italianise. L’epopea fantastorica di Enrico Brizzi 103 Alessandro Martini Une uchronie de Résistance et de football L’inattesa piega degli eventi d’Enrico Brizzi 113 La mémoire des dictatures Monica Jansen Storia, menzogna e utopia in L’amore graffia il mondo di Ugo Riccarelli e Per Isabel di Antonio Tabucchi 123 Perle Abbrugiati Tristano non invecchia in fretta 133 Stefano Magni Campo del langue Il viaggio di Eraldo Affinati attraverso la storia e la memoria 139 Hanna Serkowska Da illazioni a allucinazioni ovvero sulla cecità nella storia nei romanzi a sfondo storico di Claudio Magris 149 Anne Laure Rebreyend Réalisme postmoderne et déconstruction de l’écriture de l’Histoire dans le roman espagnol contemporain. -

Gli Anni Di Piombo Nella Letteratura E Nell'arte Degli Anni Duemila

Facultad de Filología Departamento de Filología Moderna Área de Estudios italianos Gli anni di piombo nella letteratura e nell’arte degli anni Duemila TESIS DOCTORAL AUTORA: LILIA ZANELLI DIRECTORA: CELIA ARAMBURU SÁNCHEZ SALAMANCA 2018 II Esta Tesis Doctoral ha sido realizada bajo la dirección de la Profesora Celia Aramburu Sánchez Fdo. III IV Non posso terminare questo lavoro senza ringraziare, in primo luogo, la professoressa Celia Aramburu Sánchez, per gli insegnamenti ed il tempo che mi ha dedicato fin dall’inizio di questa ricerca, per la pazienza nel rispondere ai tanti dubbi che le sottoponevo, per la passione con la quale abbiamo condiviso questo tema, per avermi saputo orientare, consigliare, correggere, e non ultimo incoraggiare durante questi anni. Grazie anche a tutti i professori dell’Área de Estudios italianos dell’Università di Salamanca i cui insegnamenti spero di essere riuscita a plasmare nell’elaborazione di questa tesi. Un ringraziamento speciale anche alla professoressa Alessandra Zanobetti che è stata mia tutor durante il mio soggiorno presso l’università di Bologna e che ho ritrovato con piacere dopo tanti anni, senza la quale la ricerca riguardante la parte giuridica di questa tesi non sarebbe stata possibile. Grazie alla mia famiglia e poi agli amici più cari che hanno sopportato le assenze, le preoccupazioni ed incertezze e in particolare a mio cugino Maurizio Morini, testimone diretto degli “anni di piombo” e fonte di ispirazione. Grazie, Javier e Paola, per il vostro amore, per l’aiuto enorme che mi avete prestato e per avere sempre creduto in me. V VI Indice ABBREVIATURE IMPIEGATE XIII INTRODUZIONE 1 1. -

Italian-Film-Miami-2019.Pdf

©2018 IMPOR TED BY BIRRA PERONI INTERNAZIONALE, W ASHINGTON, DC MOMENTI DI TRASCURABILE FELICITÀ Ordinary Happiness Showing: Friday, October 11, 2019, 7:30pm GENRE : Comedy Director: Daniele Luchetti Cast: Pierfrancesco Diliberto aka Pif, Renato Carpentieri, Federica Victoria Caiozzo aka Thony, Francesco Giammanco, Angelica Alleruzzo, Vincenzo Ferrera Screenplay: Daniele Luchetti, Francesco Piccolo Director of Photography: Matteo Tommaso Fiorilli Producer: Beppe Caschetto EFedsittoivr:a Cl laanudd iAow Dai rMdasu:• ro Music: Franco Piersanti t Year: 2019 Synopsis: Golden Ciak 2019: Nominated Best Supporting Actor; Best Score INSFJ 2019: Nominated Best Actress Filmfest München 2019: Spotligh Paolo (PIF from In Guerra per Amore and La Mafia Uccide Solo l’estate) leads a quiet life in Palermo with his wife and two children, working as an engineer in the commer - cial port. To add pepper to his days are not the extramarital affairs that he gives himself from time to time, or the sessions at the bar with friends to cheer for the pink and black soccer team, but a few moments of pure joy, like riding a moped at full speed through an urban intersection at the exact moment when all the traffic lights are red. It is a pity that the time comes when Paolo "misses" the moment by a fraction of a second, and is hit in full by a truck finding himself catapulted iInNt oIT HAeLaIAveNn W, inIT tHhe E lNarGgLeI SrHoo SmU BuTseITd LfoErS .sorting the souls that looks a lot like any large post office in any city of Italy. When his life expectancy is tabulated it becomes obvious that he was not meant to day and actually has another hour and thirty-two minutes of life left and he’s sent back, in the company of an angel, to complete his life cycle. -

Gfk Italia CERTIFICAZIONI ALBUM Fisici E Digitali Relative Alla Settimana 47 Del 2019 LEGENDA New Award

GfK Italia CERTIFICAZIONI ALBUM fisici e digitali relative alla settimana 47 del 2019 LEGENDA New Award Settimana di Titolo Artista Etichetta Distributore Release Date Certificazione premiazione ZERONOVETOUR PRESENTE RENATO ZERO TATTICA RECORD SERVICE 2009/03/20 DIAMANTE 19/2010 TRACKS 2 VASCO ROSSI CAPITOL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2009/11/27 DIAMANTE 40/2010 ARRIVEDERCI, MOSTRO! LIGABUE WARNER BROS WMI 2010/05/11 DIAMANTE 42/2010 VIVERE O NIENTE VASCO ROSSI CAPITOL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2011/03/29 DIAMANTE 19/2011 VIVA I ROMANTICI MODA' ULTRASUONI ARTIST FIRST 2011/02/16 DIAMANTE 32/2011 ORA JOVANOTTI UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2011/01/24 DIAMANTE 46/2011 21 ADELE BB (XL REC.) SELF 2011/01/25 8 PLATINO 52/2013 L'AMORE È UNA COSA SEMPLICE TIZIANO FERRO CAPITOL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2011/11/28 8 PLATINO 52/2013 TZN-THE BEST OF TIZIANO FERRO TIZIANO FERRO CAPITOL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2014/11/25 8 PLATINO 15/2017 MONDOVISIONE LIGABUE ZOO APERTO WMI 2013/11/26 7 PLATINO 18/2015 LE MIGLIORI MINACELENTANO CLAN CELENTANO SRL - PDU MUSIC SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 2016/11/11 7 PLATINO 12/2018 INEDITO LAURA PAUSINI ATLANTIC WMI 2011/11/11 6 PLATINO 52/2013 BACKUP 1987-2012 IL BEST JOVANOTTI UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2012/11/27 6 PLATINO 18/2015 SONO INNOCENTE VASCO ROSSI CAPITOL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2014/11/04 6 PLATINO 39/2015 CHRISTMAS MICHAEL BUBLE' WARNER BROS WMI 2011/10/25 6 PLATINO 51/2016 ÷ ED SHEERAN ATLANTIC WMI 2017/03/03 6 PLATINO 44/2019 CHOCABECK ZUCCHERO UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2010/10/28 5 PLATINO 52/2013 ALI E RADICI EROS RAMAZZOTTI RCA ITALIANA SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 2009/05/22 5 PLATINO 52/2013 NOI EROS RAMAZZOTTI UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2012/11/13 5 PLATINO 12/2015 LORENZO 2015 CC. -

Nederlandse Release 24 Februari 2011 Prijs Beste Acteur Filmfestival Cannes

Nederlandse release 24 februari 2011 Prijs beste acteur filmfestival Cannes - Synopsis Bouwvakker Claudio (Elio Germano) is na jaren nog steeds tot over zijn oren verliefd op zijn vrouw Elena. Het jonge stel heeft twee zoontjes, een derde kind is onderweg. Maar na een onbezorgd familieweekend slaat het noodlot hard toe. Onderweg terug naar huis krijgt de zwangere Elena weeën. Hals over kop rijdt Claudio met zijn hele gezin naar het ziekenhuis, maar Elena overleeft de bevalling niet. Hoewel zijn leven verwoest is, kan Claudio het zich niet permitteren bij de pakken neer te gaan zitten. De steun van zijn familie, van zijn vrienden en de liefde van zijn kinderen zullen Claudio uiteindelijk helpen. LA NOSTRA VITA is een ontroerend en meeslepend drama over liefde, familie en de grote veerkracht van de mens. Hoofdrolspeler Elio Germano won voor deze rol de prijs voor beste acteur op het filmfestival van Cannes 2010. 98 minuten/ 35 mm/ Kleur/ Italië 2010/ Italiaans met Nederlandse ondertiteling LA NOSTRA VITA beleeft z’n Nederlandse première op het IFFR 2011 en is vanaf 24 februari in de bioscopen te zien. LA NOSTRA VITA wordt in Nederland gedistribueerd door ABC/ Cinemien. Beeldmateriaal kan gedownload worden vanaf: www.cinemien.nl/pers of vanaf www.filmdepot.nl Voor meer informatie kunt u zich wenden tot Gideon Querido van Frank, +31(0)20-5776010 of [email protected] - Cast Claudio Elio Germano Piero Raoul Bova Elena Isabella Ragonese Ari Luca Zingaretti Loredana Stefania Montorsi Porcari Giorgio Colangeli Gabriela Alina Madalina Berzunteanu Andrei Marius Ignat Celeste Awa Ly Vittorio Emiliano Campagnola - Crew Regie Daniele Luchetti Scenario Sandro Petraglia Stefano Rulli Daniele Luchetti Productie-ontwerp Giancarlo Basili Kostuums Maria Rita Barbera Fotografie Claudio Collepiccolo Geluid Bruno Pupparo Montage Mirco Garrone Muziek Franco Piersanti Productie Ricardo Tozzi Giovanni Stabilini Marco Chimens Co-productie Fabio Conversi Matteo De Laurentis Uitvoerend producent Gina Gardini Productie i.s.m. -

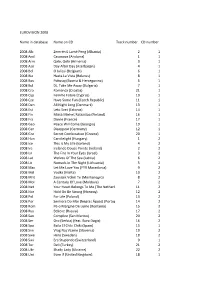

EUROVISION 2008 Name in Database Name on CD Track Number CD

EUROVISION 2008 Name in database Name on CD Track number CD number 2008 Alb Zemrën E Lamë Peng (Albania) 2 1 2008 And Casanova (Andorra) 1 1 2008 Arm Qele, Qele (Armenia) 3 1 2008 Aze Day After Day (Azerbaijan) 4 1 2008 Bel O Julissi (Belgium) 6 1 2008 Bie Hasta La Vista (Belarus) 8 1 2008 Bos Pokusaj (Bosnia & Herzegovina) 5 1 2008 Bul DJ, Take Me Away (Bulgaria) 7 1 2008 Cro Romanca (Croatia) 21 1 2008 Cyp Femme Fatale (Cyprus) 10 1 2008 Cze Have Some Fun (Czech Republic) 11 1 2008 Den All Night Long (Denmark) 13 1 2008 Est Leto Svet (Estonia) 14 1 2008 Fin Missä Miehet Ratsastaa (Finland) 16 1 2008 Fra Divine (France) 17 1 2008 Geo Peace Will Come (Georgia) 19 1 2008 Ger Disappear (Germany) 12 1 2008 Gre Secret Combination (Greece) 20 1 2008 Hun Candlelight (Hungary) 1 2 2008 Ice This Is My Life (Iceland) 4 2 2008 Ire Irelande Douze Pointe (Ireland) 2 2 2008 Isr The Fire In Your Eyes (Israel) 3 2 2008 Lat Wolves Of The Sea (Latvia) 6 2 2008 Lit Nomads In The Night (Lithuania) 5 2 2008 Mac Let Me Love You (FYR Macedonia) 9 2 2008 Mal Vodka (Malta) 10 2 2008 Mnt Zauvijek Volim Te (Montenegro) 8 2 2008 Mol A Century Of Love (Moldova) 7 2 2008 Net Your Heart Belongs To Me (The Netherlands) 11 2 2008 Nor Hold On Be Strong (Norway) 12 2 2008 Pol For Life (Poland) 13 2 2008 Por Senhora Do Mar (Negras Águas) (Portugal) 14 2 2008 Rom Pe-o Margine De Lume (Romania) 15 2 2008 Rus Believe (Russia) 17 2 2008 San Complice (San Marino) 20 2 2008 Ser Oro (Serbia) (feat. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

L'italia in 150 Libri

LL’’IIttaalliiaa iinn 115500 lliibbrrii l’Italia in 150 libri. 150 libri, uno al giorno, sull’Italia, gli italiani e l’italianità L’Italia in 150 libri 150 libri, uno al giorno, sull’Italia, gli italiani e l’italianità In occasione del 150° anniversario dell’Unità d’Italia, la Biblioteca ha predisposto uno speciale percorso di lettura che ha raccontato l’Italia e gli italiani attraverso 150 titoli significativi, scelti tra libri e altri documenti. Nel corso dell’anno, per 150 giorni, ogni giorno abbiamo proposto un titolo che è stato esposto in un apposito spazio della Biblioteca, riconoscibile perché “avvolto” dal tricolore; l’opera era corredata da una scheda sintetica di presentazione che, oltre all’argomento trattato, dava ragione dell’inclusione di quel documento all’interno di questa particolare bibliografia. Nella selezione, pur avendo privilegiato le opere più recenti, abbiamo ritenuto opportuno inserire anche alcuni classici particolarmente significativi, perché hanno contribuito alla formazione culturale degli italiani. Le schede sono qui presentate secondo l’ordine della collocazione a scaffale, per facilitarne al lettore la ricerca, ed anche perché questa classificazione consente di ordinare i materiali per affinità di argomento. All’inizio del fascicolo abbiamo inserito anche un indice ordinato per titolo, con segnata a fianco la collocazione. Ovviamente tutti i titoli selezionati sono prestabili con le consuete modalità e durante l’orario di apertura della Biblioteca. l’Italia in 150 libri. 150 libri, uno al giorno, sull’Italia, gli italiani e l’italianità ELENCO PER TITOLO (La collocazione serve a recuperare i singoli titoli nel presente repertorio e nello scaffale) 150 (anni di) invenzioni italiane / Vittorio Marchis....................................................................608.773 MAR Alpini, schutzen e kaiserjager nella Grande Guerra / Enrico Folisi ................................. -

Immortal Words: the Language and Style of the Contemporary Italian Undead-Romance Novel

Immortal Words: the Language and Style of the Contemporary Italian Undead-Romance Novel by Christina Vani A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Italian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Christina Vani 2018 Immortal Words: the Language and Style of the Contemporary Italian Undead-Romance Novel Christina Vani Doctor of Philosophy Department of Italian Studies University of Toronto 2018 Abstract This thesis explores the language and style of six “undead romances” by four contemporary Italian women authors. I begin by defining the undead romance, trace its roots across horror and romance genres, and examine the subgenres under the horror-romance umbrella. The Trilogia di Mirta-Luna by Chiara Palazzolo features a 19-year-old sentient zombie as the protagonist: upon waking from death, Mirta-Luna searches the Subasio region for her love… but also for human flesh. These novels present a unique interpretation of the contemporary “vampire romance” subgenre, as they employ a style influenced by Palazzolo’s American and British literary idols, including Cormac McCarthy’s dialogic style, but they also contain significant lexical traces of the Cannibali and their contemporaries. The final three works from the A cena col vampiro series are Moonlight rainbow by Violet Folgorata, Raining stars by Michaela Dooley, and Porcaccia, un vampiro! by Giusy De Nicolo. The first two are fan-fiction works inspired by Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight Saga, while the last is an original queer vampire romance. These novels exhibit linguistic and stylistic traits in stark contrast with the Trilogia’s, though Porcaccia has more in common with Mirta-Luna than first meets the eye. -

Poetry and the Visual in 1950S and 1960S Italian Experimental Writers

The Photographic Eye: Poetry and the Visual in 1950s and 1960s Italian Experimental Writers Elena Carletti Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2020 This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. I acknowledge that this thesis has been read and proofread by Dr. Nina Seja. I acknowledge that parts of the analysis on Amelia Rosselli, contained in Chapter Four, have been used in the following publication: Carletti, Elena. “Photography and ‘Spazi metrici.’” In Deconstructing the Model in 20th and 20st-Century Italian Experimental Writings, edited by Beppe Cavatorta and Federica Santini, 82– 101. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2019. Abstract This PhD thesis argues that, in the 1950s and 1960s, several Italian experimental writers developed photographic and cinematic modes of writing with the aim to innovate poetic form and content. By adopting an interdisciplinary framework, which intersects literary studies with visual and intermedial studies, this thesis analyses the works of Antonio Porta, Amelia Rosselli, and Edoardo Sanguineti. These authors were particularly sensitive to photographic and cinematic media, which inspired their poetics. Antonio Porta’s poetry, for instance, develops in dialogue with the photographic culture of the time, and makes references to the photographs of crime news.