Chapter 3. Early African Societies and the Bantu Migrations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pharaonic Egypt Through the Eyes of a European Traveller and Collector

Pharaonic Egypt through the eyes of a European traveller and collector Excerpts from the travel diary of Johann Michael Wansleben (1672-3), with an introduction and annotations by Esther de Groot Esther de Groot s0901245 Book and Digital Media Studies University of Leiden First Reader: P.G. Hoftijzer Second reader: R.J. Demarée 0 1 2 Pharaonic Egypt through the eyes of a European traveller and collector Excerpts from the travel diary of Johann Michael Wansleben (1672-3), with an introduction and annotations by Esther de Groot. 3 4 For Harold M. Hays 1965-2013 Who taught me how to read hieroglyphs 5 6 Contents List of illustrations p. 8 Introduction p. 9 Editorial note p. 11 Johann Michael Wansleben: A traveller of his time p. 12 Egypt in the Ottoman Empire p. 21 The journal p. 28 Travelled places p. 53 Acknowledgments p. 67 Bibliography p. 68 Appendix p. 73 7 List of illustrations Figure 1. Giza, BNF Ms. Italien 435, folio 104 p. 54 Figure 2. The pillar of Marcus Aurelius, BNF Ms. Italien 435, folio 123 p. 59 Figure 3. Satellite view of Der Abu Hennis and Der el Bersha p. 60 Figure 4. Map of Der Abu Hennis from the original manuscript p. 61 Figure 5. Map of the visited places in Egypt p. 65 Figure 6. Map of the visited places in the Faiyum p. 66 Figure 7. An offering table from Saqqara, BNF Ms. Italien 435, folio 39 p. 73 Figure 8. A stela from Saqqara, BNF Ms. Italien 435, folio 40 p. 74 Figure 9. -

African Journal of History and Culture

OPEN ACCESS African Journal of History and Culture March 2019 ISSN: 2141-6672 DOI: 10.5897/AJHC www.academicjournals.org Editors Pedro A. Fuertes-Olivera Ndlovu Sabelo University of Valladolid Ferguson Centre for African and Asian Studies, E.U.E. Empresariales ABOUTOpen University, AJHC Milton Keynes, Paseo del Prado de la Magdalena s/n United Kingdom. 47005 Valladolid Spain. Biodun J. Ogundayo, PH.D The African Journal of History and Culture (AJHC) is published monthly (one volume per year) by University of Pittsburgh at Bradford Academic Journals. Brenda F. McGadney, Ph.D. 300 Campus Drive School of Social Work, Bradford, Pa 16701 University of Windsor, USA. Canada. African Journal of History and Culture (AJHC) is an open access journal that provides rapid publication Julius O. Adekunle (monthly) of articles in all areas of the subject. TheRonen Journal A. Cohenwelcomes Ph.D. the submission of manuscripts Department of History and Anthropology that meet the general criteria of significance andDepartment scientific of excellence.Middle Eastern Papers and will be published Monmouth University Israel Studies / Political Science, shortlyWest Long after Branch, acceptance. NJ 07764 All articles published in AJHC are peer-reviewed. Ariel University Center, USA. Ariel, 40700, Percyslage Chigora Israel. Department Chair and Lecturer Dept of History and Development Studies Midlands State University ContactZimbabwe Us Private Bag 9055, Gweru, Zimbabwe. Editorial Office: [email protected] Help Desk: [email protected] Website: http://www.academicjournals.org/journal/AJHC Submit manuscript online http://ms.academicjournals.me/. Editorial Board Dr. Antonio J. Monroy Antón Dr Jephias Mapuva Department of Business Economics African Centre for Citizenship and Democracy Universidad Carlos III , [ACCEDE];School of Government; University of the Western Cape, Madrid, Spain. -

Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Curriculum Map Scope and Sequence

Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Curriculum Map Scope and Sequence Unit Length Unit Focus Standards and Practices Unit 0: Social 1 week Students will apply the social studies practices to TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Studies Skills create and address questions that will guide inquiry SSP.06 and critical thinking. Unit 1: 2 weeks Students will learn proper time designations and TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Foundations of analyze the development and characteristics of SSP.06 Human civilizations, including the effects of the Agricultural Week 1: 6.01, 6.02 Civilization Revolution. Week 2: 6.03, 6.04 Unit 2: Ancient 3 weeks Students will analyze the geographic, political, TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Mesopotamia economic, and cultural structures of the civilization of SSP.06 ancient Mesopotamia. Week 1: 6.05, 6.06, 6.07 Week 2: 6.08, 6.09, 6.10 Week 3: 6.11, 6.12 Unit 3: Ancient 3 weeks Students will analyze the geographic, political, TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Egypt economic, and cultural structures of ancient Egypt. SSP.06 Week 1: 6.13, 6.14, 6.15 Week 2: 6.16, 6.17 Week 3: 6.18, 6.19 Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Map Instructional Framework Course Description: World History and Geography: Early Civilizations Through the Fall of the Western Roman Empire Sixth grade students will study the beginnings of early civilizations through the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Students will analyze the cultural, economic, geographical, historical, and political foundations for early civilizations, including Mesopotamia, Egypt, Israel, India, China, Greece, and Rome. -

Country Advice Egypt Egypt – EGY37024 – Treatment of Anglican Christians in Al Minya 2 August 2010

Country Advice Egypt Egypt – EGY37024 – Treatment of Anglican Christians in Al Minya 2 August 2010 1. Please provide detailed information on Al Minya, including its location, its history and its religious background. Please focus on the Christian population of Al Minya and provide information on what Christian denominations are in Al Minya, including the Anglican Church and the United Coptic Church; the main places of Christian worship in Al Minya; and any conflict in Al Minya between Christians and the authorities. 1 Al Minya (also known as El Minya or El Menya) is known as the „Bride of Upper Egypt‟ due to its location on at the border of Upper and Lower Egypt. It is the capital city of the Minya governorate in the Nile River valley of Upper Egypt and is located about 225km south of Cairo to which it is linked by rail. The city has a television station and a university and is a centre for the manufacture of soap, perfume and sugar processing. There is also an ancient town named Menat Khufu in the area which was the ancestral home of the pharaohs of the 4th dynasty. 2 1 „Cities in Egypt‟ (undated), travelguide2egypt.com website http://www.travelguide2egypt.com/c1_cities.php – Accessed 28 July 2010 – Attachment 1. 2 „Travel & Geography: Al-Minya‟ 2010, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 2 August http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/384682/al-Minya – Accessed 28 July 2010 – Attachment 2; „El Minya‟ (undated), touregypt.net website http://www.touregypt.net/elminyatop.htm – Accessed 26 July 2010 – Page 1 of 18 According to several websites, the Minya governorate is one of the most highly populated governorates of Upper Egypt. -

Women's Position and Attitudes Towards Female Genital Mutilation in Egypt

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Van Rossem et al. BMC Public Health (2015) 15:874 DOI 10.1186/s12889-015-2203-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Women's position and attitudes towards female genital mutilation in Egypt: A secondary analysis of the Egypt demographic and health surveys, 1995-2014 Ronan Van Rossem1*, Dominique Meekers2 and Anastasia J. Gage2 Abstract Background: Female genital mutilation (FGM) is still widespread in Egyptian society. It is strongly entrenched in local tradition and culture and has a strong link to the position of women. To eradicate the practice a major attitudinal change is a required for which an improvement in the social position of women is a prerequisite. This study examines the relationship between Egyptian women’s social positions and their attitudes towards FGM, and investigates whether the spread of anti-FGM attitudes is related to the observed improvements in the position of women over time. Methods: Changes in attitudes towards FGM are tracked using data from the Egypt Demographic and Health Surveys from 1995 to 2014. Multilevel logistic regressions are used to estimate 1) the effects of indicators of a woman’ssocial position on her attitude towards FGM, and 2) whether these effects change over time. Results: Literate, better educated and employed women are more likely to oppose FGM. Initially growing opposition to FGM was related to the expansion of women’s education, but lately opposition to FGM also seems to have spread to other segments of Egyptian society. -

Sudan a Country Study.Pdf

A Country Study: Sudan An Nilain Mosque, at the site of the confluence of the Blue Nile and White Nile in Khartoum Federal Research Division Library of Congress Edited by Helen Chapin Metz Research Completed June 1991 Table of Contents Foreword Acknowledgements Preface Country Profile Country Geography Society Economy Transportation Government and Politics National Security Introduction Chapter 1 - Historical Setting (Thomas Ofcansky) Early History Cush Meroe Christian Nubia The Coming of Islam The Arabs The Decline of Christian Nubia The Rule of the Kashif The Funj The Fur The Turkiyah, 1821-85 The Mahdiyah, 1884-98 The Khalifa Reconquest of Sudan The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, 1899-1955 Britain's Southern Policy Rise of Sudanese Nationalism The Road to Independence The South and the Unity of Sudan Independent Sudan The Politics of Independence The Abbud Military Government, 1958-64 Return to Civilian Rule, 1964-69 The Nimeiri Era, 1969-85 Revolutionary Command Council The Southern Problem Political Developments National Reconciliation The Transitional Military Council Sadiq Al Mahdi and Coalition Governments Chapter 2 - The Society and its Environment (Robert O. Collins) Physical Setting Geographical Regions Soils Hydrology Climate Population Ethnicity Language Ethnic Groups The Muslim Peoples Non-Muslim Peoples Migration Regionalism and Ethnicity The Social Order Northern Arabized Communities Southern Communities Urban and National Elites Women and the Family Religious -

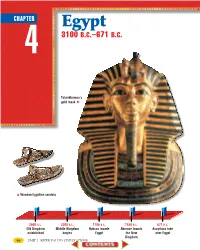

Chapter 4: Egypt, 3100 B.C

0066-0081 CH04-846240 10/24/02 5:57 PM Page 66 CHAPTER Egypt 4 3100 B.C.–671 B.C. Tutankhamen’s gold mask ᭤ ᭡ Wooden Egyptian sandals 2600 B.C. 2300 B.C. 1786 B.C. 1550 B.C. 671 B.C. Old Kingdom Middle Kingdom Hyksos invade Ahmose founds Assyrians take established begins Egypt the New over Egypt Kingdom 66 UNIT 2 RIVER VALLEY CIVILIZATIONS 0066-0081 CH04-846240 10/24/02 5:57 PM Page 67 Chapter Focus Read to Discover Chapter Overview Visit the Human Heritage Web site • Why the Nile River was so important to the growth of at humanheritage.glencoe.com Egyptian civilization. and click on Chapter 4—Chapter • How Egyptian religious beliefs influenced the Old Kingdom. Overviews to preview this chapter. • What happened during Egypt’s Middle Kingdom. • Why Egyptian civilization grew and then declined during the New Kingdom. • What the Egyptians contributed to other civilizations. Terms to Learn People to Know Places to Locate shadoof Narmer Nile River pharaoh Ahmose Punt pyramids Thutmose III Thebes embalming Hatshepsut mummy Amenhotep IV legend hieroglyphic papyrus Why It’s Important The Egyptians settled in the Nile River val- ley of northeast Africa. They most likely borrowed ideas such as writing from the Sumerians. However, the Egyptian civiliza- tion lasted far longer than the city-states and empires of Mesopotamia. While the people of Mesopotamia fought among themselves, Egypt grew into a rich, powerful, and unified kingdom. The Egyptians built a civilization that lasted for more than 2,000 years and left a lasting influence on the world. -

Submission to the University of Baltimore School of Law‟S Center on Applied Feminism for Its Fourth Annual Feminist Legal Theory Conference

Submission to the University of Baltimore School of Law‟s Center on Applied Feminism for its Fourth Annual Feminist Legal Theory Conference. “Applying Feminism Globally.” Feminism from an African and Matriarchal Culture Perspective How Ancient Africa’s Gender Sensitive Laws and Institutions Can Inform Modern Africa and the World Fatou Kiné CAMARA, PhD Associate Professor of Law, Faculté des Sciences Juridiques et Politiques, Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar, SENEGAL “The German experience should be regarded as a lesson. Initially, after the codification of German law in 1900, academic lectures were still based on a study of private law with reference to Roman law, the Pandectists and Germanic law as the basis for comparison. Since 1918, education in law focused only on national law while the legal-historical and comparative possibilities that were available to adapt the law were largely ignored. Students were unable to critically analyse the law or to resist the German socialist-nationalism system. They had no value system against which their own legal system could be tested.” Du Plessis W. 1 Paper Abstract What explains that in patriarchal societies it is the father who passes on his name to his child while in matriarchal societies the child bears the surname of his mother? The biological reality is the same in both cases: it is the woman who bears the child and gives birth to it. Thus the answer does not lie in biological differences but in cultural ones. So far in feminist literature the analysis relies on a patriarchal background. Not many attempts have been made to consider the way gender has been used in matriarchal societies. -

Barly Records on Bantu Arvi Hurskainen

Remota Relata Srudia Orientalia 97, Helsinki 20O3,pp.65-76 Barly Records on Bantu Arvi Hurskainen This article gives a short outline of the early, sometimes controversial, records of Bantu peoples and languages. While the term Bantu has been in use since the mid lgth century, the earliest attempts at describing a Bantu language were made in the lTth century. However, extensive description of the individual Bantu languages started only in the l9th century @oke l96lab; Doke 1967; Wolff 1981: 2l). Scholars have made great efforts in trying to trace the earliest record of the peoples currently known as Bantu. What is considered as proven with considerable certainty is that the first person who brought the term Bantu to the knowledge of scholars of Africa was W. H. L Bleek. When precisely this happened is not fully clear. The year given is sometimes 1856, when he published The lnnguages of Mosambique, oÍ 1869, which is the year of publication of his unfinished, yet great work A Comparative Grammar of South African Languages.In The Languages of Mosambiqu¿ he writes: <<The languages of these vocabularies all belong to that great family which, with the exception of the Hottentot dialects, includes the whole of South Africa, and most of the tongues of Western Africa>. However, in this context he does not mention the name of the language family concemed. Silverstein (1968) pointed out that the first year when the word Bantu is found written by Bleek is 1857. That year Bleek prepared a manuscript Zulu Legends (printed as late as 1952), in which he stated: <<The word 'aBa-ntu' (men, people) means 'Par excellence' individuals of the Kafir race, particularly in opposition to the noun 'aBe-lungu' (white men). -

Timeline .Pdf

Timeline of Egyptian History 1 Ancient Egypt (Languages: Egyptian written in hieroglyphics and Hieratic script) Timeline of Egyptian History 2 Early Dynastic Period 3100–2686 BCE • 1st & 2nd Dynasty • Narmer aka Menes unites Upper & Lower Egypt • Hieroglyphic script developed Left: Narmer wearing the crown of Lower Egypt, the “Deshret”, or Red Crown Center: the Deshret in hieroglyphics; Right: The Red Crown of Lower Egypt Narmer wearing the crown of Upper Egypt, the “Hedjet”, or White Crown Center: the Hedjet in hieroglyphics; Right: The White Crown of Upper Egypt Pharaoh Djet was the first to wear the combined crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, the “Pschent” (pronounced Pskent). Timeline of Egyptian History 3 Old Kingdom 2686–2181 BCE • 3rd – 6th Dynasty • First “Step Pyramid” (mastaba) built at Saqqara for Pharaoh Djoser (aka Zoser) Left: King Djoser (Zoser), Righr: Step pyramid at Saqqara • Giza Pyramids (Khufu’s pyramid – largest for Pharaoh Khufu aka Cheops, Khafra’s pyramid, Menkaura’s pyramid – smallest) Giza necropolis from the ground and the air. Giza is in Lower Egypt, mn the outskirts of present-day Cairo (the modern capital of Egypt.) • The Great Sphinx built (body of a lion, head of a human) Timeline of Egyptian History 4 1st Intermediate Period 2181–2055 BCE • 7th – 11th Dynasty • Period of instability with various kings • Upper & Lower Egypt have different rulers Middle Kingdom 2055–1650 BCE • 12th – 14th Dynasty • Temple of Karnak commences contruction • Egyptians control Nubia 2nd Intermediate Period 1650–1550 BCE • 15th – 17th Dynasty • The Hyksos come from the Levant to occupy and rule Lower Egypt • Hyksos bring new technology such as the chariot to Egypt New Kingdom 1550–1069 BCE (Late Egyptian language) • 18th – 20th Dynasty • Pharaoh Ahmose overthrows the Hyksos, drives them out of Egypt, and reunites Upper & Lower Egypt • Pharaoh Hatshepsut, a female, declares herself pharaoh, increases trade routes, and builds many statues and monuments. -

Contagious Faith- Talking About God Without Being Weird.Key

Acts 8:26–30: 26 Now an angel of the Lord said to Philip, “Go south to the road—the desert road—that goes down from Jerusalem to Gaza.” 27 So he started out, and on his way he met an Ethiopian eunuch, an important official in charge of all the treasury of the Kandake (which means “queen of the Ethiopians”). This man had gone to Jerusalem to worship, 28 and on his way home was sitting in his chariot reading the Book of Isaiah the prophet. 29 The Spirit told Philip, “Go to that chariot and stay near it.” 30 Then Philip ran up to the chariot and heard the man reading Isaiah the prophet. “Do you understand what you are reading?” Philip asked. Acts 8:31–35: 31 “How can I,” he said, “unless someone explains it to me?” So he invited Philip to come up and sit with him. 32 This is the passage of Scripture the eunuch was reading: “He was led like a sheep to the slaughter, and as a lamb before its shearer is silent, so he did not open his mouth. 33 In his humiliation he was deprived of justice. Who can speak of his descendants? For his life was taken from the earth.” 34 The eunuch asked Philip, “Tell me, please, who is the prophet talking about, himself or someone else?” 35 Then Philip began with that very passage of Scripture and told him the good news about Jesus. Acts 8:36–40: As they traveled along the road, they came to some water and the eunuch said, “Look, here is water. -

Kush Under the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty (C. 760-656 Bc)

CHAPTER FOUR KUSH UNDER THE TWENTY-FIFTH DYNASTY (C. 760-656 BC) "(And from that time on) the southerners have been sailing northwards, the northerners southwards, to the place where His Majesty is, with every good thing of South-land and every kind of provision of North-land." 1 1. THE SOURCES 1.1. Textual evidence The names of Alara's (see Ch. 111.4.1) successor on the throne of the united kingdom of Kush, Kashta, and of Alara's and Kashta's descen dants (cf. Appendix) Piye,2 Shabaqo, Shebitqo, Taharqo,3 and Tan wetamani are recorded in Ancient History as kings of Egypt and the c. one century of their reign in Egypt is referred to as the period of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty.4 While the political and cultural history of Kush 1 DS ofTanwetamani, lines 4lf. (c. 664 BC), FHNI No. 29, trans!. R.H. Pierce. 2 In earlier literature: Piankhy; occasionally: Py. For the reading of the Kushite name as Piye: Priese 1968 24f. The name written as Pyl: W. Spiegelberg: Aus der Geschichte vom Zauberer Ne-nefer-ke-Sokar, Demotischer Papyrus Berlin 13640. in: Studies Presented to F.Ll. Griffith. London 1932 I 71-180 (Ptolemaic). 3 In this book the writing of the names Shabaqo, Shebitqo, and Taharqo (instead of the conventional Shabaka, Shebitku, Taharka/Taharqa) follows the theoretical recon struction of the Kushite name forms, cf. Priese 1978. 4 The Dynasty may also be termed "Nubian", "Ethiopian", or "Kushite". O'Connor 1983 184; Kitchen 1986 Table 4 counts to the Dynasty the rulers from Alara to Tanwetamani.