Pharaonic Egypt Through the Eyes of a European Traveller and Collector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 the Cinderella Story in Antiquity

2 THE CINDERELLA STORY IN ANTIQUITY Cinderella can fairly be claimed as the best known of fairytales in modern times, as well as the first tale to be subjected to attempts at the ‘exhaustive’ collecting of its variants. It was long assumed that the story, or rather group of stories, did not date much further back than the early seventeenth century, when a recognisable form of it appeared as Basile’s La Gatta Cenerentola.1 But from time to time throughout this century discoveries have been made to show that the tale must be much older, and few who have seriously examined the evidence would be tempted to measure the tale as a whole by the yardstick of its most famous example, the version published by Charles Perrault in 1697.2 It can now be seen that a number of the Perrault features such as glass slipper, pumpkin coach, clock striking midnight, and others, are not essential, or even necessarily characteristic, of the orally transmitted story. Taken as a whole, the hundreds of versions known present the heroine under a variety of names: Cinderella, Ashiepattle and Popelutschka are the most obvious European variations; sometimes she has sisters (often less beautiful, rather than ugly), sometimes not; sometimes she has a fairy godmother helper, sometimes a helpful animal or plant, sometimes even a fairy godfather, or some combination of such forces. The basic framework for the story printed by Aarne-Thompson can be slightly abridged as follows:3 I The persecuted heroine 1. The heroine is abused by her stepmother and stepsisters; she stays on the hearth and ashes; and 2. -

Country Advice Egypt Egypt – EGY37024 – Treatment of Anglican Christians in Al Minya 2 August 2010

Country Advice Egypt Egypt – EGY37024 – Treatment of Anglican Christians in Al Minya 2 August 2010 1. Please provide detailed information on Al Minya, including its location, its history and its religious background. Please focus on the Christian population of Al Minya and provide information on what Christian denominations are in Al Minya, including the Anglican Church and the United Coptic Church; the main places of Christian worship in Al Minya; and any conflict in Al Minya between Christians and the authorities. 1 Al Minya (also known as El Minya or El Menya) is known as the „Bride of Upper Egypt‟ due to its location on at the border of Upper and Lower Egypt. It is the capital city of the Minya governorate in the Nile River valley of Upper Egypt and is located about 225km south of Cairo to which it is linked by rail. The city has a television station and a university and is a centre for the manufacture of soap, perfume and sugar processing. There is also an ancient town named Menat Khufu in the area which was the ancestral home of the pharaohs of the 4th dynasty. 2 1 „Cities in Egypt‟ (undated), travelguide2egypt.com website http://www.travelguide2egypt.com/c1_cities.php – Accessed 28 July 2010 – Attachment 1. 2 „Travel & Geography: Al-Minya‟ 2010, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 2 August http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/384682/al-Minya – Accessed 28 July 2010 – Attachment 2; „El Minya‟ (undated), touregypt.net website http://www.touregypt.net/elminyatop.htm – Accessed 26 July 2010 – Page 1 of 18 According to several websites, the Minya governorate is one of the most highly populated governorates of Upper Egypt. -

A Brief History of Coptic Personal Status Law Ryan Rowberry Georgia State University College of Law, [email protected]

Georgia State University College of Law Reading Room Faculty Publications By Year Faculty Publications 1-1-2010 A Brief History of Coptic Personal Status Law Ryan Rowberry Georgia State University College of Law, [email protected] John Khalil Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/faculty_pub Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Human Rights Law Commons Recommended Citation Ryan Rowberry & John Khalil, A Brief History of Coptic Personal Status Law, 3 Berk. J. Middle E. & Islamic L. 81 (2010). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications By Year by an authorized administrator of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Brief History of Coptic Personal Status Law Ryan Rowberry John Khalil* INTRODUCTION With the U.S.-led "War on Terror" and the occupation of Iraq and Afghanistan, American legal scholars have understandably focused increased attention on the various schools and applications of Islamic law in Middle Eastern countries. 1 This focus on Shari'a law, however, has tended to elide the complexity of traditional legal pluralism in many Islamic nations. Numerous Christian communities across the Middle East (e.g., Syrian, Armenian, Coptic, Nestorian, Maronite), for example, adhere to personal status laws that are not based on Islamic legal principles. Christian minority groups form the largest non-Muslim . Ryan Rowberry and Jolin Khalil graduated from Harvard Law School in 2008. Ryan is currently a natural resources associate at Hogan Lovells US LLP in Washington D.C., and John Khalil is a litigation associate at Lowey, Dannenberg, Cowey & Hart P.C. -

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

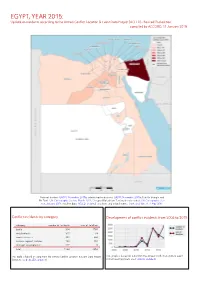

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

Egypt: Vocabulary Terms (2)

Name: Period: Egypt: Vocabulary Terms (2) Definition Example Sentence Symbol/Picture Nile River: Main water source for ancient Egypt, flows south to north, emptying into the Mediterranean Sea. Flooding of this river brought rich silt (soil) to the Nile River Valley for farming. Cataracts: Wild and difficult to navigate rapids that choke the Nile River through southern Egypt. Made travel difficult. Delta: A triangle shaped formation at the mouth of a river, created by deposit of sediment. Often fan shaped with smaller rivers splitting up and flowing into the larger body of water. Sahara Desert: The largest desert in the world, located to the west of Ancient Egypt. Name: Period: Egypt: Vocabulary Terms (2) Definition Example Sentence Symbol/Picture Kemet: Means “black land.” The Egyptians called their lanf Kemet because of the the dark, fertile mud (silt) left behind by the Nile’s annual floods. Shaduf: Irrigation device invented in Egypt-a bucket attached to a long pole to dip into the river. Still used by egyptian farmers today. Upper Egypt: The southern area of Egypt, where the city of Thebes and the Valley of the Kings are located. Called “Upper Egypt” because of higher elevation. Lower Egypt: The northern area of Egypt, where the Nile River delta, the Great Pyramids at Giza and the city of Cairo are located. Called “Lower Egypt” because of lower elevation. Name: Period: Egypt: Vocabulary Terms (2) Definition Example Sentence Symbol/Picture Memphis: Capital city of the Old Kingdom, located in Lower Egypt, founded by Pharaoh Menes. Strategically located as a link between Upper and Lower Egypt. -

A Short History of Egypt – to About 1970

A Short History of Egypt – to about 1970 Foreword................................................................................................... 2 Chapter 1. Pre-Dynastic Times : Upper and Lower Egypt: The Unification. .. 3 Chapter 2. Chronology of the First Twelve Dynasties. ............................... 5 Chapter 3. The First and Second Dynasties (Archaic Egypt) ....................... 6 Chapter 4. The Third to the Sixth Dynasties (The Old Kingdom): The "Pyramid Age"..................................................................... 8 Chapter 5. The First Intermediate Period (Seventh to Tenth Dynasties)......10 Chapter 6. The Eleventh and Twelfth Dynasties (The Middle Kingdom).......11 Chapter 7. The Second Intermediate Period (about I780-1561 B.C.): The Hyksos. .............................................................................12 Chapter 8. The "New Kingdom" or "Empire" : Eighteenth to Twentieth Dynasties (c.1567-1085 B.C.)...............................................13 Chapter 9. The Decline of the Empire. ...................................................15 Chapter 10. Persian Rule (525-332 B.C.): Conquest by Alexander the Great. 17 Chapter 11. The Early Ptolemies: Alexandria. ...........................................18 Chapter 12. The Later Ptolemies: The Advent of Rome. .............................20 Chapter 13. Cleopatra...........................................................................21 Chapter 14. Egypt under the Roman, and then Byzantine, Empire: Christianity: The Coptic Church.............................................23 -

The Legal Status of Tiran and Sanafir Islands Rajab, 1438 - April 2017

22 Dirasat The Legal Status of Tiran and Sanafir Islands Rajab, 1438 - April 2017 Askar H. Enazy The Legal Status of Tiran and Sanafir Islands Askar H. Enazy 4 Dirasat No. 22 Rajab, 1438 - April 2017 © King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies, 2017 King Fahd National Library Cataloging-In-Publication Data Enazy, Askar H. The Legal Status of Tiran and Sanafir Island. / Askar H. Enazy, - Riyadh, 2017 76 p ; 16.5 x 23 cm ISBN: 978-603-8206-26-3 1 - Islands - Saudi Arabia - History 2- Tiran, Strait of - Inter- national status I - Title 341.44 dc 1438/8202 L.D. no. 1438/8202 ISBN: 978-603-8206-26-3 Table of Content Introduction 7 Legal History of the Tiran-Sanafir Islands Dispute 11 1928 Tiran-Sanafir Incident 14 The 1950 Saudi-Egyptian Accord on Egyptian Occupation of Tiran and Sanafir 17 The 1954 Egyptian Claim to Tiran and Sanafir Islands 24 Aftermath of the 1956 Suez Crisis: Egyptian Abandonment of the Claim to the Islands and Saudi Assertion of Its Sovereignty over Them 26 March–April 1957: Saudi Press Statement and Diplomatic Note Reasserting Saudi Sovereignty over Tiran and Sanafir 29 The April 1957 Memorandum on Saudi Arabia’s “Legal and Historical Rights in the Straits of Tiran and the Gulf of Aqaba” 30 The June 1967 War and Israeli Reoccupation of Tiran and Sanafir Islands 33 The Status of Tiran and Sanafir Islands in the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty of 1979 39 The 1988–1990 Egyptian-Saudi Exchange of Letters, the 1990 Egyptian Decree 27 Establishing the Egyptian Territorial Sea, and 2016 Statements by the Egyptian President -

Nationalism and Minority Identities in Islamic Societies'

H-Nationalism Kern on Shatzmiller, 'Nationalism and Minority Identities in Islamic Societies' Review published on Friday, September 1, 2006 Maya Shatzmiller, ed. Nationalism and Minority Identities in Islamic Societies. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2005. xiii + 346 pp. $80.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-7735-2847-5; $27.95 (paper), ISBN 978-0-7735-2848-2. Reviewed by Karen M. Kern (Assistant Professor, Department of History, Hunter College, City University of New York) Published on H-Nationalism (September, 2006) Accommodation or Resistance? Strategies in Minority-State Relations This volume of essays, edited by Maya Shatzmiller, is a timely, solidly researched collection on the topic of national identity formation among religious and ethnic minorities in Muslim-majority countries. These essays were presented on December 8-9, 2001 at a conference called "to discuss current research and to analyze recent developments in the field of ethnicity in Islamic societies" at the University of Western Ontario (p. xiii). Shatzmiller establishes the volume's thematic basis by noting that the secular model of nation-building excluded any minority identity that was not aligned with state ideology. Therefore, minority communities separated themselves from the Muslim majority by creating identities that were based on culture, religion and language. Shatzmiller suggests that certain factors such as state-sponsored hostilities and exclusion from institutional structures resulted in the politicization of minority identities. The editor's declared aim is to create a broader framework for comparative analysis, and with this goal in mind she has chosen essays in political science, history and anthropology. The minority populations included in this volume have been examined before by other scholars from various disciplines. -

Pollen Atlas of the Flora of Egypt 5. Species of Scrophulariaceae

Pollen Atlas of the flora of Egypt * 5. Species of Scrophulariaceae Nahed El-Husseini and Eman Shamso. The Herbarium, Faculty of Science, Cairo University, Giza 12613, Egypt. El-Husseini, N. & Shamso, E. 2002. The pollen atlas of the flora of Egypt. 5. Species of Scrophulariaceae. Taeckholmia 22(1): 65-76. Light and scanning electron microscope study of the pollen grains of 47 species representing 16 genera of Scrophulariaceae in Egypt was carried out. Pollen grains vary from subspheroidal to prolate; trizonocolpate to trizonocolporate. Exine’s sculpture is striate, colliculate, granulate, coarse reticulate or microreticulate. Seven pollen types are recognized and briefly described, a key distinguishing the different pollen types and the discussion of its systematic value are provided. Key words: Flora of Egypt, pollen atlas, Scrophulariaceae. Introduction The Scrophulariaceae is a family of about 292 genera and nearly 3000 species of cosmopolitan distribution. It is represented in the flora of Egypt by 50 species belonging to 16 genera, 8 tribes and 3 sub-families (El-Hadidi et al., 1999). Within the family, a wide range of pollen morphology exists and provides not only an additional parameter for generic delimitation but also reinforces the validity of many of the larger taxa. Erdtman (1952), gave a concise account of the pollen morphology of some members of the family. Several authors studied and described the pollen of species of the family among whom to mention: Risch (1939), Ikuse (1956), Natarajan (1957), Verghese (1968), Olsson (1974), Elisens (1985c & 1986), Bolliger & Wick (1990) and Argu (1980, 1990 & 1993). Material and Methods Pollen grains of 47 species representing 16 genera of Scrophulariaceae were the subject of the present investigation. -

Kalasiris and Charikleia: Mentorship and Intertext in Heliodorus' Aithiopika

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2017 Kalasiris and Charikleia: Mentorship and Intertext in Heliodorus' Aithiopika Lauren Jordan Wood College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Wood, Lauren Jordan, "Kalasiris and Charikleia: Mentorship and Intertext in Heliodorus' Aithiopika" (2017). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1004. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1004 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kalasiris and Charikleia: Mentorship and Intertext in Heliodorus’ Aithiopika A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Classical Studies from The College of William and Mary by Lauren Wood Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ William Hutton, Director ________________________________________ Vassiliki Panoussi ________________________________________ Suzanne Hagedorn Williamsburg, VA April 17, 2017 Wood 2 Kalasiris and Charikleia: Mentorship and Intertext in Heliodorus’ Aithiopika Odyssean and more broadly Homeric intertext figures largely in Greco-Roman literature of the first to third centuries AD, often referred to in scholarship as the period of the Second Sophistic.1 Second Sophistic authors work cleverly and often playfully with Homeric characters, themes, and quotes, echoing the traditional stories in innovative and often unexpected ways. First to fourth century Greek novelists often play with the idea of their protagonists as wanderers and exiles, drawing comparisons with the Odyssey and its hero Odysseus. -

Johann Michael Wansleben1 on the Coptic Church

Johann Michael Wansleben1 on the Coptic Church Anthony Alcock The text that follows translates the chapter 'Relatione dello stato eccelesiastico dei Copti' on pp. 130-221 of the book entitled Relazione dell Stato presente dell'Egitto, written after Wansleben's first stay in Egypt and published in 1671. When he made the journey, he was a Protestant. When the report was written and published, he was a Catholic. Johann Michael Wansleben (1635-1679) was born in Sömmerda.2 After studying at Erfurt and Königsberg, Wansleben became a private tutor in an aristocratic family in Marienwerder, but left this employment to join the Prussian army and fight in the 1657 campaign against Poland. 3 After a brief period he returned to Erfurt, where he met Hiob Ludolf, a distinguished Ethiopic scholar and tutor of the children of Ernst, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha,4 who took him on as an assistant because he saw that Wansleben had a talent for learning languages. He learned enough Ethiopic to oversee the printing of Ludolf's dictionary in 1661 in London,5 there being no suitable ones in Germany after the ravages of the Thirty Year War, which had ended only 13 years previously. While there, he made changes to Ludolf's work, which may not have pleased the great scholar. In 1663 he started out on a journey to Ethiopia, financed by the Duke. The background to this is that Ernst some years before had been introduced by Ludolf to an Ethiopian prelate. Ludolf convinced Ernst that Ethiopia might be fertile ground for the spread of Lutheranism. -

Sappho's Brothers Song and the Fictionality of Early Greek Lyric Poetry

chapter 7 Sappho’s Brothers Song and the Fictionality of Early Greek Lyric Poetry André Lardinois It is a good time to be working on Sappho.1 Twelve years ago two new poems were published, including the so-called Tithonos poem, in which Sappho (or better: the I-person) complains about the onset of old age.2 The number of publications devoted to this poem was starting to dry up, when suddenly a new set of papyri was discovered in 2014. One might be forgiven for suspecting that a creative papyrologist was behind these finds, but it looks like the papyri are genuine and that we owe them to the gods and to the enduring popularity of Sappho’s poetry in antiquity. The new discovery consists of five papyrus fragments, preserving the re- mains of no less than nine poems of Sappho.3 Among these are five com- plete stanzas of a previously unknown song, which Obbink has labelled ‘Broth- ers Poem’ or ‘Brothers Song’.4 This article deals mainly with this poem, pre- served on P. Sapph. Obbink and re-edited by Obbink in the opening chapter of this volume. The argument consists of four parts. First I will say some- thing about the authenticity of the Brothers Song. Next I will discuss what we know about Sappho’s brothers from the ancient biographical tradition and other fragments of Sappho. Then I will discuss the content of the Broth- ers Song in more detail and, finally, I will present my interpretation of the song. 1 Oral versions of this paper were delivered at the universities of Amsterdam, Basel, Groningen, Leiden, Nijmegen and Oxford.