British Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migratory Birds Index

CAFF Assessment Series Report September 2015 Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index ARCTIC COUNCIL Acknowledgements CAFF Designated Agencies: • Norwegian Environment Agency, Trondheim, Norway • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland • Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Reykjavik, Iceland • Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Greenland • Russian Federation Ministry of Natural Resources, Moscow, Russia • Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Stockholm, Sweden • United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska CAFF Permanent Participant Organizations: • Aleut International Association (AIA) • Arctic Athabaskan Council (AAC) • Gwich’in Council International (GCI) • Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) • Russian Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) • Saami Council This publication should be cited as: Deinet, S., Zöckler, C., Jacoby, D., Tresize, E., Marconi, V., McRae, L., Svobods, M., & Barry, T. (2015). The Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, Akureyri, Iceland. ISBN: 978-9935-431-44-8 Cover photo: Arctic tern. Photo: Mark Medcalf/Shutterstock.com Back cover: Red knot. Photo: USFWS/Flickr Design and layout: Courtney Price For more information please contact: CAFF International Secretariat Borgir, Nordurslod 600 Akureyri, Iceland Phone: +354 462-3350 Fax: +354 462-3390 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.caff.is This report was commissioned and funded by the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF), the Biodiversity Working Group of the Arctic Council. Additional funding was provided by WWF International, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). The views expressed in this report are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Arctic Council or its members. -

European Red List of Birds

European Red List of Birds Compiled by BirdLife International Published by the European Commission. opinion whatsoever on the part of the European Commission or BirdLife International concerning the legal status of any country, Citation: Publications of the European Communities. Design and layout by: Imre Sebestyén jr. / UNITgraphics.com Printed by: Pannónia Nyomda Picture credits on cover page: Fratercula arctica to continue into the future. © Ondrej Pelánek All photographs used in this publication remain the property of the original copyright holder (see individual captions for details). Photographs should not be reproduced or used in other contexts without written permission from the copyright holder. Available from: to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed Published by the European Commission. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. ISBN: 978-92-79-47450-7 DOI: 10.2779/975810 © European Union, 2015 Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Printed in Hungary. European Red List of Birds Consortium iii Table of contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................................1 Executive summary ...................................................................................................................................................5 1. -

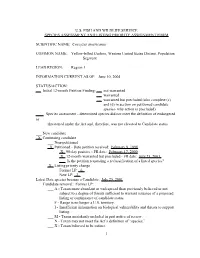

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Species Assessment and Listing Priority Assignment Form

U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE SPECIES ASSESSMENT AND LISTING PRIORITY ASSIGNMENT FORM SCIENTIFIC NAME: Coccyzus americanus COMMON NAME: Yellow-billed Cuckoo, Western United States Distinct Population Segment LEAD REGION: Region 1 INFORMATION CURRENT AS OF: June 10, 2004 STATUS/ACTION: Initial 12-month Petition Finding: not warranted warranted warranted but precluded (also complete (c) and (d) in section on petitioned candidate species- why action is precluded) Species assessment - determined species did not meet the definition of endangered or threatened under the Act and, therefore, was not elevated to Candidate status ___ New candidate X Continuing candidate ___ Non-petitioned X Petitioned - Date petition received: February 9, 1998 X 90-day positive - FR date: February 17, 2000 X 12-month warranted but precluded - FR date: July 25, 2001 Is the petition requesting a reclassification of a listed species? X Listing priority change Former LP: 6 New LP: 3 Latest Date species became a Candidate: July 25, 2001 ___ Candidate removal: Former LP: ___ ___ A - Taxon more abundant or widespread than previously believed or not subject to a degree of threats sufficient to warrant issuance of a proposed listing or continuance of candidate status. ___ F - Range is no longer a U.S. territory. I - Insufficient information on biological vulnerability and threats to support listing. ___ M - Taxon mistakenly included in past notice of review. ___ N - Taxon may not meet the Act’s definition of “species.” ___ X - Taxon believed to be extinct. 1 ANIMAL/PLANT GROUP AND FAMILY: Family Cuculidae and Order Cuculiformes HISTORICAL STATES/TERRITORIES/COUNTRIES OF OCCURRENCE: California, Oregon, Washington, Arizona, Colorado, Montana, Idaho, Nevada, Wyoming, New Mexico, Texas, Utah, British Columbia, and Mexico. -

PETITION to LIST the QUEEN CHARLOTTE GOSHAWK Accipiter Gentilis Laingi AS a FEDERALLY ENDANGERED SPECIES

PETITION TO LIST THE QUEEN CHARLOTTE GOSHAWK Accipiter gentilis laingi AS A FEDERALLY ENDANGERED SPECIES May 2, 1994 May 2, 1994 Mr. Bruce Babbitt Secretary of the Interior Department of the Interior 18th and "C" Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20240 Dear Mr. Babbitt, The Southwest Center for Biological Diversity, the Greater Gila Biodiversity Project, the Biodiversity Legal Foundation, Greater Ecosystem Alliance, Save the West, Save America's Forests, Native Forest Network, Native Forest Council, Peter Galvin, Eric Holle, and Don Muller hereby formally petition to list the Queen Charlotte goshawk (Accipiter gentilis laingi) as endangered pursuant to the Endangered Species Act, 16 U.S.C. 1531 et seg. This petition is filed under 5 U.S.C. 553(e) and 50 C.F.R 424.14(a) which grant interested parties the right to petition for issue of a rule from the Assistant Secretary of the Interior. Petitioners also request that Critical Habitat be designated for the Queen Charlotte goshawk concurrent with the listing, pursuant to 50 C.F.R 424.12, and pursuant to the Administrative Procedures Act 5 U.S.C. 553. Petitioners understand that this petition action sets in motion a specific process placing definite response requirements on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and very specific time constraints upon those responses. Petitioners The Southwest Center for Biological Diversity is dedicated to protecting and restoring the Southwest's island forests and desert rivers by aggressively advocating for every level of biotic diversity, from butterflies to jaguars. This petition is part of the Center's ongoing efforts to conserve goshawks throughout the West. -

Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland 2020-2026 Amber-List Species (Medium Conservation Concern)

Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland 2020-2026 Amber-list species (medium conservation concern) Breeding Breeding continued Wintering continued Goosander Swallow Smew Garganey Sand Martin Pintail Spotted Crake Willow Warbler Black-throated Diver European Storm-petrel Starling Great Northern Diver Fulmar Spotted Flycatcher Bittern Manx Shearwater Northern Wheatear Turnstone Gannet Goldcrest Brambling Shag House Sparrow Little Ringed Plover Tree Sparrow Breeding and Wintering Common Sandpiper Greenfinch Mute Swan Mediterranean Gull Linnet Whooper Swan Little Tern Pied Flycatcher Red-breasted Merganser Roseate Tern Western Yellow Wagtail Shelduck Common Tern Tufted Duck Arctic Tern Passage Gadwall Sandwich Tern Cory's Shearwater Wigeon Great Skua Ruff Mallard Black Guillemot Spotted Redshank Teal Common Guillemot Wood Sandpiper Great Crested Grebe Short-eared Owl Little Gull Coot Marsh Harrier Black Tern Red-throated Diver Hen Harrier Wryneck Cormorant Goshawk Tree Pipit Ringed Plover Kingfisher Black-headed Gull Merlin Wintering Common Gull Chough Brent Goose Lesser Black-backed Gull Skylark Barnacle Goose European Herring Gull Bearded Reedling Greylag Goose House Martin Greater White-fronted Goose For more information, please see Gilbert G, Stanbury A and Lewis L (2021), “Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland 2020 –2026”. Irish Birds 9: 523—544 The categorisation of species as breeding, wintering etc. refers to the populations against which BoCCI criteria were applied Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland 2020-2026 Red-list species -

Changing Numbers of Three Gull Species in the British Isles AND

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten 1 1 Send proof to: 2 Ruedi Nager 3 Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine 4 Graham Kerr Building 5 University of Glasgow 6 Glasgow G12 8QQ 7 Phone: ++44 141 3305976 8 Email: [email protected] 9 10 11 Changing Numbers of Three Gull Species in the British Isles 12 1,* 2 13 RUEDI G. NAGER AND NINA J. O’HANLON 14 15 1Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine, Graham Kerr Building 16 University of Glasgow, Glasgow, G12 8QQ, Scotland, U.K. 17 18 2Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine, The Scottish Centre for 19 Ecology and the Natural Environment, University of Glasgow, Rowardennan, Drymen, 20 Glasgow, G63 0AW, Scotland, U.K. 21 22 *Corresponding author; E-mail: [email protected] 23 2 24 Abstract.—Between-population variation of changes in numbers can provide insights 25 into factors influencing variation in demography and how population size or density is 26 regulated. Here, we describe spatio-temporal patterns of population change of Herring Gull 27 (Larus argentatus), Lesser Black-backed Gull (L. fuscus) and Great Black-backed Gull (L. 28 marinus) in the British Isles from national censuses and survey data. The aim of this study 29 was to test for density-dependence and spatial variation in population trends as two possible, 30 but not mutually exclusive, explanations of population changes with important implications 31 for the understanding of these changes. Between 1969 and 2013 the three species showed 32 different population trends with Herring Gulls showing a strong decline, Great Black-backed 33 Gulls a less pronounced decline and Lesser Black-backed Gulls an increase until 2000 but 34 then a decline since. -

Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index

CAFF Assessment Series Report September 2015 Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index ARCTIC COUNCIL Acknowledgements CAFF Designated Agencies: • Norwegian Environment Agency, Trondheim, Norway • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland • Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Reykjavik, Iceland • Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Greenland • Russian Federation Ministry of Natural Resources, Moscow, Russia • Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Stockholm, Sweden • United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska CAFF Permanent Participant Organizations: • Aleut International Association (AIA) • Arctic Athabaskan Council (AAC) • Gwich’in Council International (GCI) • Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) • Russian Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) • Saami Council This publication should be cited as: Deinet, S., Zöckler, C., Jacoby, D., Tresize, E., Marconi, V., McRae, L., Svobods, M., & Barry, T. (2015). The Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, Akureyri, Iceland. ISBN: 978-9935-431-44-8 Cover photo: Arctic tern. Photo: Mark Medcalf/Shutterstock.com Back cover: Red knot. Photo: USFWS/Flickr Design and layout: Courtney Price For more information please contact: CAFF International Secretariat Borgir, Nordurslod 600 Akureyri, Iceland Phone: +354 462-3350 Fax: +354 462-3390 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.caff.is This report was commissioned and funded by the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF), the Biodiversity Working Group of the Arctic Council. Additional funding was provided by WWF International, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). The views expressed in this report are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Arctic Council or its members. -

Aythya Nyroca

Aythya nyroca -- (Güldenstädt, 1770) ANIMALIA -- CHORDATA -- AVES -- ANSERIFORMES -- ANATIDAE Common names: Ferruginous Duck; Ferruginous Pochard; Fuligule nyroca; Porrón Pardo; White-eyed Pochard European Red List Assessment European Red List Status LC -- Least Concern, (IUCN version 3.1) Assessment Information Year published: 2015 Date assessed: 2015-03-31 Assessor(s): BirdLife International Reviewer(s): Symes, A. Compiler(s): Ashpole, J., Burfield, I., Ieronymidou, C., Pople, R., Wheatley, H. & Wright, L. Assessment Rationale European regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) EU27 regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) In Europe this species has an extremely large range, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence 10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure). The population trend is not known, but the population is not believed to be decreasing sufficiently rapidly to approach the thresholds under the population trend criterion (30% decline over ten years or three generations). For these reasons the species is evaluated as Least Concern in Europe. Within the EU27 this species has a very large range, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence 10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure). The population trend is not known, but the population is not believed to be decreasing sufficiently rapidly to approach the thresholds under the population -

Checklists of Protected and Threatened Species in Ireland. Irish Wildlife Manuals, No

ISSN 1393 – 6670 N A T I O N A L P A R K S A N D W I L D L I F E S ERVICE CHECKLISTS OF PROTECTED AND THREATENED SPECIES IN IRELAND Brian Nelson, Sinéad Cummins, Loraine Fay, Rebecca Jeffrey, Seán Kelly, Naomi Kingston, Neil Lockhart, Ferdia Marnell, David Tierney and Mike Wyse Jackson I R I S H W I L D L I F E M ANUAL S 116 National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) commissions a range of reports from external contractors to provide scientific evidence and advice to assist it in its duties. The Irish Wildlife Manuals series serves as a record of work carried out or commissioned by NPWS, and is one means by which it disseminates scientific information. Others include scientific publications in peer reviewed journals. The views and recommendations presented in this report are not necessarily those of NPWS and should, therefore, not be attributed to NPWS. Front cover, small photographs from top row: Coastal heath, Howth Head, Co. Dublin, Maurice Eakin; Red Squirrel Sciurus vulgaris, Eddie Dunne, NPWS Image Library; Marsh Fritillary Euphydryas aurinia, Brian Nelson; Puffin Fratercula arctica, Mike Brown, NPWS Image Library; Long Range and Upper Lake, Killarney National Park, NPWS Image Library; Limestone pavement, Bricklieve Mountains, Co. Sligo, Andy Bleasdale; Meadow Saffron Colchicum autumnale, Lorcan Scott; Barn Owl Tyto alba, Mike Brown, NPWS Image Library; A deep water fly trap anemone Phelliactis sp., Yvonne Leahy; Violet Crystalwort Riccia huebeneriana, Robert Thompson Main photograph: Short-beaked Common Dolphin Delphinus delphis, -

Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland 2020-2026 Amber-List Species (Medium Conservation Concern)

Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland 2020-2026 Amber-list species (medium conservation concern) Breeding Breeding continued Wintering continued Goosander Swallow Smew Garganey Sand Martin Pintail Spotted Crake Willow Warbler Black-throated Diver European Storm-petrel Starling Great Northern Diver Fulmar Spotted Flycatcher Bittern Manx Shearwater Northern Wheatear Turnstone Gannet Goldcrest Brambling Shag House Sparrow Little Ringed Plover Tree Sparrow Breeding and Wintering Common Sandpiper Greenfinch Mute Swan Mediterranean Gull Linnet Whooper Swan Little Tern Pied Flycatcher Red-breasted Merganser Roseate Tern Western Yellow Wagtail Shelduck Common Tern Tufted Duck Arctic Tern Passage Gadwall Sandwich Tern Cory's Shearwater Wigeon Great Skua Ruff Mallard Black Guillemot Spotted Redshank Teal Common Guillemot Wood Sandpiper Great Crested Grebe Short-eared Owl Little Gull Coot Marsh Harrier Black Tern Red-throated Diver Hen Harrier Wryneck Cormorant Goshawk Tree Pipit Ringed Plover Kingfisher Black-headed Gull Merlin Wintering Common Gull Chough Brent Goose Lesser Black-backed Gull Skylark Barnacle Goose European Herring Gull Bearded Reedling Greylag Goose House Martin Greater White-fronted Goose For more information, please see Gilbert G, Stanbury A and Lewis L (2021), “Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland 2020 –2026”. Irish Birds 43: 1–22 The categorisation of species as breeding, wintering etc. refers to the populations against which BoCCI criteria were applied Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland 2020-2026 Red-list species -

Order Anseriformes: from Check-List of Birds of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Paul Johnsgard Collection Papers in the Biological Sciences 1979 Order Anseriformes: from Check-List of Birds of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Order Anseriformes: from Check-List of Birds of the World" (1979). Paul Johnsgard Collection. 32. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard/32 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paul Johnsgard Collection by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. From: Check-List of Birds of the World, Volume I, Second Edition. Edited by Ernst Mayr and G. William Cottrell. Cambridge, MA: Museum of Comparative Zoology, 1979. Copyright 1979 The President and Fellows of Harvard College. ————— ORDER ANSERIFORMES by Paul A. Johnsgard pp. 425–506 425 ORDER ANSERIFORMES1 PAUL A. JOHNSGARD SUBORDER ANSERES FAMILY ANATIDAE cf. Delacour and Mayr, 1945-46, Wilson Bull., 57, pp. 3-55, 58, pp. 104-110 (classification). Rellmayr and Conover, 1948, Publ. Field Mus. Nat. Rist., 'MS read by F. McKinney, P. Scott, D. W. Snow (African forms), and M. W. Weller. 426 CHECK-LIST OF BIRDS OF THE WORLD Zool. Ser., 13, pt. 1, no. 2, pp. 283-415 (New World). Dementiev et al., 1952, Ptitsy Sovetskogo Soiuza, 4, pp. 247-635 (English trans., 1967, Birds Soviet Union, 4, pp. 276-683). -

Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland 4: 2020–2026

Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland 4: 2020–2026 Gillian Gilbert1, Andrew Stanbury2 & Lesley Lewis3 1 RSPB Northern Ireland, Belvoir Park Forest, Belfast BT8 7QT 2 RSPB The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire SG192DL 3 BirdWatch Ireland, Unit 20, Block D, Bullford Business Campus, Kilcoole, Greystones, Co. Wicklow, A63 RW83, Ireland Corresponding author: [email protected] Keywords: Priority, population, decline, Red list, breeding, wintering This is the fourth review of the status of birds in Ireland. Two hundred and eleven species were assessed and assigned to the Red, Amber or Green list of conservation concern. The criteria mainly follow previous assessments of conservation status at global and European levels; and within Ireland, include historical decline, trends in population and range, rarity, localised distribution and interna- tional importance. The availability of more data has allowed us to move closer towards the ideal time windows of existing criteria. Results show 23 species moving onto the Red list and only six leaving it. Twelve species are newly Red-listed due to changed European or global status. Three are Red-listed due to declines within the expanded short-term breeding time period. There is no doubt that having 54 (25.6%) of Ireland’s regularly occurring bird species now on the Red list is alarming, with some species having shown dramatic declines and losses on this island. Existing conservation concerns are reinforced, such as the further catastrophic decline of waders with six more wading bird species joining the Red list; and generalist birds of farmland, like Kestrel Falco tinnunculus now Red-listed. When grouped by habitat, upland (50%) and farmland (35%) have the highest proportions of Red-listed species.