Aythya Nyroca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplementary Material

Aythya ferina (Common Pochard) European Red List of Birds Supplementary Material The European Union (EU27) Red List assessments were based principally on the official data reported by EU Member States to the European Commission under Article 12 of the Birds Directive in 2013-14. For the European Red List assessments, similar data were sourced from BirdLife Partners and other collaborating experts in other European countries and territories. For more information, see BirdLife International (2015). Contents Reported national population sizes and trends p. 2 Trend maps of reported national population data p. 6 Sources of reported national population data p. 9 Species factsheet bibliography p. 17 Recommended citation BirdLife International (2015) European Red List of Birds. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. Further information http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/info/euroredlist http://www.birdlife.org/europe-and-central-asia/european-red-list-birds-0 http://www.iucnredlist.org/initiatives/europe http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/conservation/species/redlist/ Data requests and feedback To request access to these data in electronic format, provide new information, correct any errors or provide feedback, please email [email protected]. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ BirdLife International (2015) European Red List of Birds Aythya ferina (Common Pochard) Table 1. Reported national breeding population size and trends in Europe1. Country (or Population estimate Short-term population trend4 -

Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Tribe Aythyini (Pochards) Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Tribe Aythyini (Pochards)" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 13. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Tribe Aythyini (Pochards) Drawing on preceding page: Canvasback (Schonwetter, 1960) to 1,360 g (Ali & Ripley, Pink-headed Duck 1968). Eggs: 44 x 41 mm, white, 45 g. Rhodonessa caryophyllacea (Latham) 1790 Identification and field marks. Length 24" (60 em). Other vernacular names. None in general English Adult males have a bright pink head, which is use. Rosenkopfente (German); canard a tete rose slightly tufted behind, the color extending down the (French); pato de cabeza rosada (Spanish). hind neck, while the foreneck, breast, underparts, and upperparts are brownish black, except for some Subspecies and range. No subspecies recognized. Ex pale pinkish markings on the mantle, scapulars, and tinct; previously resident in northern India, prob breast. -

The Systematic Position of the Ring-Necked Duck

460 Hollister, Ring-necked Duck. [o"t. into consideration the evanescence of the diagnostic markings, and the inaccessibility of the coastal marshes where the bird breeds, together with the fact that the few ornithologists who seem to have visited them were generally armed only with cameras, it is perhaps not so odd after all. In assembling the data upon which these notes are based, besides those already mentioned, to whom I am particularly indebted, my thanks are due to Messrs. Stanley C. Arthur, O. Bangs, Howarth S. Boyle, William Brewster, Jonathan Dwight, J. H. Flemming, Harry C. Oberholser, Wilfred H. Osgood, T. S. Palmer, H. S. Swarth, P. A. Taverner, W. E. Clyde Todd, and John E. Thayer. THE SYSTEMATIC POSITION OF THE RING-NECKED DUCK. BY N. HOLLISTER. The group of fuliguline Ducks now called Marila in the American ' Ornithologists' Union Check-List ' has had its full share of nomen- clatorial shifts and changes, and many schemes have been proposed for its division into genera or subgenera. It has always seemed to me that the question of the number and rank of the named super- specific sections within this group is of little importance in com- parison to the error involved in the sequence given the species in the ' Check-List,' where the Canvasback is placed between the Redhead and the Scaups, and the Ring-necked Duck is put at the end of the series in the typical subgenus Marila. From a study of the literature of American Ducks it is evident that the belief prevails that the Ring-necked Duck (Marila col- laris) is a Scaup, very closely related to the Greater and Lesser Bluebills (Marila marila and M. -

Bird Species Checklist

6 7 8 1 COMMON NAME Sp Su Fa Wi COMMON NAME Sp Su Fa Wi Bank Swallow R White-throated Sparrow R R R Bird Species Barn Swallow C C U O Vesper Sparrow O O Cliff Swallow R R R Savannah Sparrow C C U Song Sparrow C C C C Checklist Chickadees, Nuthataches, Wrens Lincoln’s Sparrow R U R Black-capped Chickadee C C C C Swamp Sparrow O O O Chestnut-backed Chickadee O O O Spotted Towhee C C C C Bushtit C C C C Black-headed Grosbeak C C R Red-breasted Nuthatch C C C C Lazuli Bunting C C R White-breasted Nuthatch U U U U Blackbirds, Meadowlarks, Orioles Brown Creeper U U U U Yellow-headed Blackbird R R O House Wren U U R Western Meadowlark R O R Pacific Wren R R R Bullock’s Oriole U U Marsh Wren R R R U Red-winged Blackbird C C U U Bewick’s Wren C C C C Brown-headed Cowbird C C O Kinglets, Thrushes, Brewer’s Blackbird R R R R Starlings, Waxwings Finches, Old World Sparrows Golden-crowned Kinglet R R R Evening Grosbeak R R R Ruby-crowned Kinglet U R U Common Yellowthroat House Finch C C C C Photo by Dan Pancamo, Wikimedia Commons Western Bluebird O O O Purple Finch U U O R Swainson’s Thrush U C U Red Crossbill O O O O Hermit Thrush R R To Coast Jackson Bottom is 6 Miles South of Exit 57. -

ND2 As an Additional Genetic Marker to Improve Identification of Diving Ducks Involved in Bird Strikes Sarah A

Human–Wildlife Interactions 14(3):365–375, Winter 2020 • digitalcommons.usu.edu/hwi ND2 as an additional genetic marker to improve identification of diving ducks involved in bird strikes Sarah A. M. Luttrell, Division of Birds, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 10th and Constitution Ave. NW, Washington, DC 20560, USA [email protected] Sergei Drovetski,1 Division of Birds, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institu- tion, 10th and Constitution Ave. NW, Washington, DC 20560, USA Nor Faridah Dahlan, Division of Birds, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 10th and Constitution Ave. NW, Washington, DC 20560, USA Damani Eubanks,2 Division of Birds, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institu- tion, 10th and Constitution Ave. NW, Washington, DC 20560, USA Carla J. Dove, Division of Birds, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 10th and Constitution Ave. NW, Washington, DC 20560, USA Abstract: Knowing the exact species of birds involved in damaging collisions with aircraft (bird strikes) is paramount to managing and preventing these types of human–wildlife conflicts. While a standard genetic marker, or DNA barcode (mitochondrial DNA gene cytochrome-c oxidase 1, or CO1), can reliably identify most avian species, this marker cannot distinguish among some closely related species. Diving ducks within the genus Aythya are an example of congeneric waterfowl involved in bird strikes where several species pairs cannot be reliably identified with the standard DNA barcode. Here, we describe methods for using an additional genetic marker (mitochondrial DNA gene NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2, or ND2) for identification of 9Aythya spp. Gene-specific phylogenetic trees and genetic distances among taxa reveal that ND2 is more effective than CO1 at genetic identification of diving ducks studied here. -

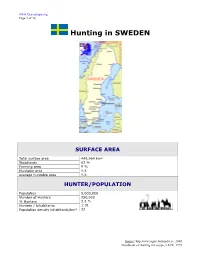

Hunting in SWEDEN

www.face-europe.org Page 1 of 14 Hunting in SWEDEN SURFACE AREA Total surface area 449,964 km² Woodlands 62 % Farming area 9 % Huntable area n.a. average huntable area n.a. HUNTER/POPULATION Population 9,000,000 Number of Hunters 290,000 % Hunters 3.2 % Hunters / Inhabitants 1:31 Population density inhabitants/km² 22 Source: http:www.jagareforbundet.se, 2005 Handbook of Hunting in Europe, FACE, 1995 www.face-europe.org Page 2 of 14 HUNTING SYSTEM Competent authorities The Parliament has overall responsibility for legislation. The Government - the Ministry of Agriculture - is responsible for questions concerning hunting. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency is responsible for supervision and monitoring developments in hunting and game management. The County Administrations are responsible for hunting and game management questions on the county level, and are advised by County Game Committees - länsviltnämnd - with representatives of forestry, agriculture, hunting, recreational and environmental protection interests. } Ministry of Agriculture (Jordbruksdepartementet) S-10333 Stockholm Phone +46 (0) 8 405 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 64 96 } Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (Naturvårdsverket) SE-106 48 Stockholm Phone +46 (0)8 698 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 29 25 Hunters’ associations Hunting is a popular sport in Sweden. There are some 290.000 hunters, of whom almost 195.000 are affiliated to the Swedish Association for Hunting and Wildlife Management (Svenska Jägareförbundet). The association is a voluntary body whose main task is to look after the interests of hunting and hunters. The Parliament has delegated responsibility SAHWM for, among other things, practical game management work. -

The Status of Ferruginous Duck Aythya Nyroca Breeding and Wintering in China

116 The status of Ferruginous Duck Aythya nyroca breeding and wintering in China ZHAO XUMAO1,2 & ROLLER MAMING1* 1Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Urumqi, Xinjiang 830011, P.R. China. 2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, P.R. China. *Correspondence author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Analysis of data published in the China Bird Report (CBR) and other literature between 1979 and 2013, along with our own field observations, found that the Ferruginous Duck Aythya nyroca now occurs throughout most of China. This contrasts with the situation in 1979, when the species was restricted to a few areas in the west of the country. Ferruginous Duck is predominately a winter visitor to China; up to 850 birds have been counted in Yunnan Province, 4,000 in Sichuan Province, and the wintering population is estimated at 6,000–8,000 individuals. In summer, the breeding population is estimated at 3,000–4,000 individuals (1,500–2,000 pairs), with highest concentrations in Xinjiang (c. 900–1,700 individuals) and Inner Mongolia (750–1,400 individuals). In China, females lay 6–11 eggs, which hatch in early June. The present population in China is likely to have spread from neighbouring central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan or Mongolia). Since 1980, the climate had gradually changed from warm-dry conditions to a wetter climate in northwest China, making it a more suitable breeding area for this species and providing corridors for their expansion to the east. If the present trend continues, southern China could in the near future become an important wintering area for a duck species that is now increasingly common elsewhere in China. -

Migratory Birds Index

CAFF Assessment Series Report September 2015 Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index ARCTIC COUNCIL Acknowledgements CAFF Designated Agencies: • Norwegian Environment Agency, Trondheim, Norway • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland • Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Reykjavik, Iceland • Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Greenland • Russian Federation Ministry of Natural Resources, Moscow, Russia • Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Stockholm, Sweden • United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska CAFF Permanent Participant Organizations: • Aleut International Association (AIA) • Arctic Athabaskan Council (AAC) • Gwich’in Council International (GCI) • Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) • Russian Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) • Saami Council This publication should be cited as: Deinet, S., Zöckler, C., Jacoby, D., Tresize, E., Marconi, V., McRae, L., Svobods, M., & Barry, T. (2015). The Arctic Species Trend Index: Migratory Birds Index. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, Akureyri, Iceland. ISBN: 978-9935-431-44-8 Cover photo: Arctic tern. Photo: Mark Medcalf/Shutterstock.com Back cover: Red knot. Photo: USFWS/Flickr Design and layout: Courtney Price For more information please contact: CAFF International Secretariat Borgir, Nordurslod 600 Akureyri, Iceland Phone: +354 462-3350 Fax: +354 462-3390 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.caff.is This report was commissioned and funded by the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF), the Biodiversity Working Group of the Arctic Council. Additional funding was provided by WWF International, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). The views expressed in this report are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Arctic Council or its members. -

Diurnal Time-Activity Budgets in Wintering Ferruginous Pochard Aythya Nyroca in Tanguar Haor, Bangladesh

FORKTAIL 20 (2004): 25–27 Diurnal time-activity budgets in wintering Ferruginous Pochard Aythya nyroca in Tanguar Haor, Bangladesh SABIR BIN MUZAFFAR Diurnal time-activity budgets were quantified for Ferruginous Pochard Aythya nyroca wintering in Tanguar Haor, Bangladesh. Individuals spent most time resting (60%), with less time spent feeding (17%), preening (14%) and swimming (9%). The time spent feeding was generally lower than for other Aythya species in winter, perhaps because Ferruginous Pochard feed preferentially at night. Human disturbance during the day may be a significant factor driving this. INTRODUCTION STUDY AREA The Ferruginous Pochard Aythya nyroca is widely The Haor basin is located in the north-eastern region distributed in Europe, Asia and Africa, but it has of Bangladesh. It contains the floodplains of the undergone declines in its populations and changes in Meghna river tributaries and it is characterised by distribution over the past few decades (Ali and Ripley numerous shallow water bodies known locally as beels, 1978, Perennou et al. 1994, Callaghan 1997, Lopez which coalesce in the wet season to form larger water and Mundkur 1997, Grimmett et al. 1999, Islam 2003, bodies (Rashid 1977, NERP 1993, Geisen et al. 2000). Robinson and Hughes 2003a,b). The primary reasons Tanguar Haor is one of the most important wetland for its decline are habitat degradation and loss and areas located near the northern reaches of the Haor hunting for local consumption (Callaghan 1997, basin (NERP 1993, Geisen et al. 2000). With a total Robinson and Hughes 2003a). The species is a winter area of 9,527 ha it is among the least disturbed of water visitor to the Indian subcontinent, where pressures on bodies in the area (NCSIP-1 2001a). -

Temporal Changes in the Sex Ratio of the Common Pochard Aythya Ferina Compared to Four Other Duck Species at Martin Mere, Lancashire, UK

140 Temporal changes in the sex ratio of the Common Pochard Aythya ferina compared to four other duck species at Martin Mere, Lancashire, UK RUSSELL T. FREW1,*, KANE BRIDES1, TOM CLARE2, LAURI MACLEAN1, DOMINIC RIGBY3, CHRISTOPHER G. TOMLINSON2 & KEVIN A. WOOD1 1Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, Slimbridge, Gloucestershire GL2 7BT, UK. 2Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, Martin Mere, Fish Lane, Burscough, Lancashire L40 0TA, UK. 3Conservation Contracts Northwest Ltd. Horwich, Bolton, Lancashire BL6 7AX, UK. *Correspondence author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Duck populations tend to have male-biased adult sex ratios (ASRs). Changes in ASR reflect species demographic rates; increasingly male-biased populations are at risk of decline when the bias results from falling female survival. European and North African Common Pochard Aythya ferina numbers have declined since the 1990s and show increasing male bias, based on samples from two discrete points in time. However, lack of sex ratio (SR) data for common duck species inhibits assessing the pattern of change in the intervening period. Here, we describe changes in annual SR during winters 1991/92–2005/06 for five duck species (Common Pochard, Gadwall Mareca strepera, Northern Pintail Anas acuta, Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata and Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula) at Martin Mere, Lancashire, UK. Pochard, Pintail, Tufted Duck and Shoveler showed significantly male-biased SRs, with the male bias increasing in Pochard and Shoveler, exhibiting a weak decrease in Pintail, and with no significant trend recorded for Tufted Duck or Gadwall. The increasing male-biased Pochard SR at Martin Mere contrasts with the stable trend for Britain, suggesting that site trends may not reflect those at the national level. -

Red-Breasted Goose

Urgent preliminary assessment of ornithological data relevant to spread of Avian Influenza in Europe Ward Hagemeijer Wetlands International Commissioned by DG Environment to Wetlands International and Euring Data needs for risk assessment: ornithology (virology) Quantified risk assessment: Research and Monitoring programme A. Birds as a vector 1.Quantified bird migration information: satellite telemetry, ringing data analysis, count data analysis 2.Quantified frequency of occurrence of virus in wild birds: surveillance 3.Ecology of virus in wild birds: virological research on wild birds B. Impact on wild bird populations Different components of the project Activities to be undertaken: • identification of Higher Risk Species (HRS) • analysis of their migration routes (ringing and count data) • identification of concentration and mixing sites • rapid assessment planning for wetland sites Analysis of higher risk species Identification of HRS on basis of: • occurence of LPAI viruses • ecology and behaviour • contact risk with poultry • numbers within EU In collaboration with David Stroud and Rowena Langston Occurrence of LPAI in wild birds species Results 1999 – 2004 Erasmus University Netherlands Species N Tested N PCR+ (%) N Egg + Mallard 6822 489 (7.2) 267 Eurasian Wigeon 1470 22 (1.5) 4 Common Teal 670 18 (2.7) 4 Northern Pintail 135 4 (3.0) 1 Northern Shoveler 90 1 (1.1) 1 Shelduck, Eider, Gadwall, Tufted, Garganey 238 0 (0.0) 0 Greater White-fronted Goose 1696 19 (1.1) 5 Greylag Goose 303 8 (2.6) 4 Brent, Barnacle, Bean, Egyptian, Canada, Pink-f 1202 0 (0.0) 0 Black-headed Gull 993 10 (1.0) 6 Common, Herring, Black-backed, Kittiwake 1976 0 (0.0) 0 Guillemot 698 3 (0.4) 1 Other birds 10909 0 0 + + + 27204 574 (2.1) 295 Selection of taxonomic groups • Anseriformes and Charadriiformes, • Migratory • Occurring in Europe. -

Canvasback Aythya Valisineria

Canvasback Aythya valisineria Class: Aves Order: Anseriformes Family: Anatidae Characteristics: A large diving duck, in fact the largest in its genus, the canvasback weighs about 2.5-3 pounds. The male has a chestnut-red head, red eyes, light white-grey body and blackish breast and tail. The female has a lighter brown head and neck that gets progressively darker brown toward the back of the body. Both sexes have a blackish bill and bluish-grey legs and feet. Range & Habitat: Behavior: Breeds in prairie potholes and A wary bird that is very swift in flight. They prefer to dive in shallow water winters on ocean bays to feed and will also feed on the water surface (Audubon). Reproduction: Several males will court and display to one female. Once a female chooses the male, they will form a monogamous bond through breeding season. They build a floating nest in stands of dense vegetation above shallow water and lay 7-12 olive-grey eggs. Often redheads will lay their eggs in canvasback nests which will result in canvasbacks laying fewer eggs. The female incubates the eggs which hatch after 23-28 days. The young feed themselves and mom leads them to water within hours of hatching. Lifespan: up to 20 years in Diet: captivity, 10 years in the wild. Wild: Seeds, plant material, snails and insect larvae, they dive to eat the roots and bases of plants Special Adaptations: They go Zoo: Scratch grains, greens, waterfowl pellets from freshwater marshes in summer to saltwater ocean bays in Conservation: winter. Some say the populations are decreasing while others say they are increasing due to habitat restoration and the ban on lead shot.