Shattered Nilometers LETTERS After 5,200 Years of Top-Down Rule

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Felucca Letter-CC - Google Docs

1/14/2019 Felucca Letter-CC - Google Docs January 14, 2019 Dear Blank, I just got back from an amazing trip to Egypt. I took sixty students along with me. Man, what a nightmare getting everyone a passport and the proper shots. We took a 747 out of SFO, that’s San Francisco International Airport, and the flight took over TWENTY hours, twelve to London, a four hour lay over, then another four hours to Cairo. When we finally got to our hotel we were so tired we didn’t notice how nice it actually was. We spent three nights in the Four Season Cairo at the Nile. What a spectacular hotel! The pool is amazing with four hot tubs and a swim up bar. Of course, Mrs. M and I couldn’t enjoy the bar, except for a soda, as we were traveling with 60 rambunctious sixth graders, but...maybe next time. Most incredible though was finally visiting all the sites I been teaching my students about for the past 28 years. Finally, I got to see Khufu’s Great Pyramid at Giza and the impressive monument to Ramses II at Abu Simbel. But, my two favorite sites are actually less wellknown. Both Hatshepsut’s temple at DayralBahri and Senusret’s White Chapel have amazing stories behind their construction. My favorite site was Hatshepsut's temple at DayralBahri. Hatshepsut was the first really powerful female pharaoh. She loved to be viewed as a man, and often wore a false beard, the symbol of divine kingship. -

Nile Serenity Felucca Sailing on the Nile

Nile Serenity Sunset Canapés Felucca Felucca Sailing on the Nile $37/person English Cheddar Cheese & Pickles, Baguette Smoked Chicken Breast & Sweet Mango Relish Smoked Salmon & Capers, Whole Wheat Bread Smoked Beef & Oriental Pickles Smoked Turkey, Sun Dry Tomato On Rye Bread Feta Cheese, Olives & Cucumber, Shammi Inclusive of one soft drink and water Beverages Bellini Cocktail LE 280 / Drink Champagne & Sparkling Moet & Chandon, 0.75l LE 5345 Valmont Cuvée Aida White 0.75l LE 760 Experience Felucca sailing from the Hilton promenade. Valmont Cuvée Aida Rose 0.75l LE 760 Choice of timings available, with a selection of catering options Omar Khayyam, Egypt 0.75l LE 677 White/Red wine Sailings* Cape Bay, Okay , 0.75l LE 933 7 am to 5 pm South Africa. * Sailing timing may change as per local regulations White/Red wine Price is inclusive of Vat & Service chare Price is inclusive of Vat & Service chare Minimum charge of 2 persons per felucca Minimum charge of 2 persons per felucca Breakfast Felucca Lunch Felucca Continental Breakfast Felucca Continental Menu Felucca $25 /person $40 /person Fresh Orange Juice Hand Picked Local Rocket Leaves Fresh Seasonal Fruit Salad Roast Vegetables, Feta Cheese & Balsamic Dressing Baker’s Basket Fresh Baked Breads and Arabic Bread Butter Butter & Preserves *** Coffee Family Style Herb Roast Chicken Herb Mash Potates, Seasonal Vegetables **************************** Full Breakfast Felucca Porcini Mushroom Sauce $35 /person *** Orange Juice Walnut Brownies Yoghurt Seasonal Fruits Cheese and Cold Cut Platter -

03 Nola.Indd

JIA 6.1 (2019) 41–80 Journal of Islamic Archaeology ISSN (print) 2051-9710 https://doi.org/10.1558/jia.37248 Journal of Islamic Archaeology ISSN (print) 2051-9729 Dating Early Islamic Sites through Architectural Elements: A Case Study from Central Israel Hagit Nol Universität Hamburg [email protected] The development of the chronology of the Early Islamic period (7th-11th centuries) has largely been based on coins and pottery, but both have pitfalls. In addition to the problem of mobility, both coins and pottery were used for extended periods of time. As a result, the dating of pottery can seldom be refined to less than a 200-300-year range, while coins in Israel are often found in contexts hundreds of years after the intial production of the coin itself. This article explores an alternative method for dating based on construction techniques and installation designs. To that end, this paper analyzes one excavation area in central Israel between Tel-Aviv, Ashdod and Ramla. The data used in the study is from excavations and survey of early Islamic remains. Installation and construction techniques were categorized by type and then ordered chronologi- cally through a common stratigraphy from related sites. The results were mapped to determine possible phases of change at the site, with six phases being established and dated. This analysis led to the re-dating of the Pool of the Arches in Ramla from 172 AH/789 CE to 272 AH/886 CE, which is different from the date that appears on the building inscription. The attempted recon- struction of Ramla involved several scattered sites attributed to the 7th and the 8th centuries which grew into clusters by the 9th century and unified into one main cluster with the White Mosque at its center by the 10th-11th centuries. -

Make a Boat for the Nile

Make a boat for the Nile The Nile was Egypt’s highway. There weren’t any roads or bridges in Egypt so boats were used for transport. Everything including mummies could be carried in them. The first boats were made from reeds or papyrus and these were commonly used in the shallow marshy water. They were called feluccas. Here’s how to make a felucca just like the ancient Egyptians. Materials you need • One bunch of straw cut to 30 cm • Bamboo skewers lengths • Optional square of linen or canvas • String • Plasticine or modelling clay • Glue Method Step 1 Make up three bundles of straw to two centimetres thickness each. Tie each bundle separately at both ends. Cut one bundle in half so you have two 15 centimetre lengths. Tie the loose ends together. Place the shorter bundles firmly together and tie at the top and the bottom again. This will become the base of the boat. Step 2 Take the two long bundles and tie them together at one end. Wedge the shorter bundles between the longer ones, pushing them firmly together. Put ties across the boat at two centimetre intervals all the way to the end to hold securely. Step 3 Attach a string to one end of the boat, thread it through the middle tie and loop it around the other end. Pull the string to make your boat curve. Secure the other end when you have the shape you want. Make an oar by cutting a bamboo skewer in half and decorating with a blob of plasticine or modelling clay. -

Clipper Ships ~4A1'11l ~ C(Ji? ~·4 ~

2 Clipper Ships ~4A1'11l ~ C(Ji? ~·4 ~/. MODEL SHIPWAYS Marine Model Co. YOUNG AMERICA #1079 SEA WITCH Marine Model Co. Extreme Clipper Ship (Clipper Ship) New York, 1853 #1 084 SWORDFISH First of the famous Clippers, built in (Medium Clipper Ship) LENGTH 21"-HEIGHT 13\4" 1846, she had an exciting career and OUR MODEL DEPARTMENT • • • Designed and built in 1851, her rec SCALE f."= I Ft. holds a unique place in the history Stocked from keel to topmast with ship model kits. Hulls of sailing vessels. ord passage from New York to San of finest carved wood, of plastic, of moulded wood. Plans and instructions -··········-·············· $ 1.00 Francisco in 91 days was eclipsed Scale 1/8" = I ft. Models for youthful builders as well as experienced mplete kit --·----- $10o25 only once. She also engaged in professionals. Length & height 36" x 24 " Mahogany hull optional. Plan only, $4.QO China Sea trade and made many Price complete as illustrated with mahogany Come a:r:1d see us if you can - or send your orders and passages to Canton. be assured of our genuine personal interest in your Add $1.00 to above price. hull and baseboard . Brass pedestals . $49,95 selection. Scale 3/32" = I ft. Hull only, on 3"t" scale, $11.50 Length & height 23" x 15" ~LISS Plan only, $1.50 & CO., INC. Price complete as illustrated with mahogany hull and baseboard. Brass pedestals. POSTAL INSTRUCTIONS $27.95 7. Returns for exchange or refund must be made within 1. Add :Jrt postage to all orders under $1 .00 for Boston 10 days. -

8Th National Summit on Coastal & Estuarine Restoration and 25Th

8th National Summit on Coastal & Estuarine Restoration and 25th Biennial Meeting of The Coastal Society Hilton New Orleans Riverside December 12, 2016 11:00 – 12:30 THE PISCINE GEOGRAPHY OF COASTAL AND ESTUARINE HABITATS – Don Davis, Louisiana Sea Grant College Program A Working Coast is a landscape of “Invisible” People, particularly from a historical perspective. The Human Mosaic English Vietnamese Portuguese Lebanese Norwegians Danes Swedes Americans Scots Poles Malays French Filipinos Spanish Laotian Chinese Austrians/ Italians Yugoslavians Germans Cajuns Greeks Isleños Irish African Latin American Americans Native Americans Tri-Racial Jews Groups THE LABOR FORCE “I enclose the receipts for advances to the oyster shuckers. I understand that advances to tenants come back out of the crops which the tenants make, and the advances to boats come back out of the oysters which the boats catch, and that this means that although we pay 40¢ or 45¢ or even 50¢ for oysters delivered at the factory, we take out of this money which we pay for the oysters the amounts due from the several boats respectively. .” Joseph S. Clark, Sr., Philadelphia, Pa., to E. A. McIlhenny, Avery Island, La., 26 December 1908, TLS. Bohemians from Baltimore Image courtesy of the McIlhenny Company Archives, Avery Island, La. WOMEN WERE THE BACKBONE OF THE FISHERY’S LABOR FORCE CHILD LABOR LEWIS HINES Bluffton, SC, ca. 1913 Bayou LaBatre, AL, ca. 1912 Biloxi, MS, ca. 1911 Dunbar & Dukate, New Orleans, LA, Alabama Canning Co., ca 1910 ca. 1911 Work in canneries was originally -

MEREKEELE NÕUKOJA Koosoleku Teokiri Nr 80 09.04.2013 Veeteede

MEREKEELE NÕUKOJA Koosoleku teokiri nr 80 09.04.2013 Veeteede Amet Tallinn, Valge tn 4 Algus kell 14.00, lõpp 16.00 Osavõtjad: Malle Hunt, Peedu Kass, Uno Laur, Taidus Linikoja, Aado Luksepp, Ants Raud, Rein Raudsalu, Tauri Roosipuu, Madli Vitismann, Peeter Veegen, Ants Ärsis. Juhataja: Peedu Kass Kirjutaja: Malle Hunt 1. Mälestasime leinaseisakuga meie seast lahkunud nõukoja liiget Ain Eidastit. 2. Vastasime terminoloogi küsimustele. Pikem selgitus terminitele port ja harbour Peeter Veegen: Meil Tallinnas on "Port of Tallinn" administratiiv-juriidiline ettevõte, mille koosseisus mitu väiksemat sadamat, mida võime tõlkida "harbour" (Paljassaare Harbour, Old Harbour, Paldiski Harbour). Ajalooliselt on pigemini kujunenud nii, et Harbour on varjumis- ja seismise koht laevadele, millel võib olla erinevaid funktsioone (nt. Miinisadam, Lennusadam, Hüdrograafiasadam jne.) Ehk ka "Last harbour" - viimne varjupaik. Port on seevastu kauba käitlemise, lastimise-lossimise, reisijate teenendamise koht- teiste sõnadega ühendus maa ja mere vahel (ka arvutil on mitu "porti" ühenduseks maailmaga). Merekaubavedudel kasutame mõisted "Port of call", "Port of destination" Vene keelest leiame analoogiana gavanj = harbour, port = port Eesti keeles on meil mõlemal juhul sadam, nii et neid kattuvaid mõisteid võime kasutada nii ja naa, aga kontekstist lähtuvalt võiks siiski tõlkes ajaloolist tausta arvestada. Madli Vitismann: - "port" on enam ettevõte, terminalide kogum ja muu lastimisega seotu - sadamaettevõtted Port of Tallinn ja Ports of Stockholm (samuti mitut sadamat koondav ettevõte). Või Paldiski Northern Port kui omaette sadamaettevõte. - "harbour" on pigem sadam kui konkreetne sadamabassein, sildumiskoht jm, nt Old City harbour Tallinna Sadama koosseisus ja Kapellskär Stockholmi Sadamate koosseisus - nende kodulehel on rubriik "Ship in harbour" http://www.stockholmshamnar.se/en/ . Ka rootsi keeles on üks vaste sõnale "sadam" - "hamn". -

Long Memory, Wavelets, and the Nile River B

WATER RESOURCES RESEARCH, VOL. 38, NO. 5, 1054, 10.1029/2001WR000509, 2002 Testing for homogeneity of variance in time series: Long memory, wavelets, and the Nile River B. Whitcher,1 S. D. Byers,2 P. Guttorp,3 and D. B. Percival4 Received 13 March 2001; revised 9 November 2001; accepted 9 November 2001; published 15 May 2002. [1] We consider the problem of testing for homogeneity of variance in a time series with long memory structure. We demonstrate that a test whose null hypothesis is designed to be white noise can, in fact, be applied, on a scale by scale basis, to the discrete wavelet transform of long memory processes. In particular, we show that evaluating a normalized cumulative sum of squares test statistic using critical levels for the null hypothesis of white noise yields approximately the same null hypothesis rejection rates when applied to the discrete wavelet transform of samples from a fractionally differenced process. The point at which the test statistic, using a nondecimated version of the discrete wavelet transform, achieves its maximum value can be used to estimate the time of the unknown variance change. We apply our proposed test statistic on five time series derived from the historical record of Nile River yearly minimum water levels covering 622–1922 A.D., each series exhibiting various degrees of serial correlation including long memory. In the longest subseries, spanning 622–1284 A.D., the test confirms an inhomogeneity of variance at short time scales and identifies the change point around 720 A.D., which coincides closely with the construction of a new device around 715 A.D. -

Sailing Alone Around the World by Joshua Slocum

Project Gutenberg's Sailing Alone Around The World, by Joshua Slocum This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Sailing Alone Around The World Author: Joshua Slocum Illustrator: Thomas Fogarty George Varian Posting Date: October 12, 2010 Release Date: August, 2004 [EBook #6317] [This file was first posted on November 25, 2002] [Last updated: August 16, 2012] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SAILING ALONE AROUND THE WORLD *** Produced by D Garcia, Juliet Sutherland, Charles Franks HTML version produced by Chuck Greif. SAILING ALONE AROUND THE WORLD The "Spray" from a photograph taken in Australian waters. SAILING ALONE AROUND THE WORLD By Captain Joshua Slocum Illustrated by THOMAS FOGARTY AND GEORGE VARIAN TO THE ONE WHO SAID: "THE 'SPRAY' WILL COME BACK." CONTENTS CHAPTER I A blue-nose ancestry with Yankee proclivities—Youthful fondness for the sea—Master of the ship Northern Light—Loss of the Aquidneck—Return home from Brazil in the canoe Liberdade—The gift of a "ship"—The rebuilding of the Spray—Conundrums in regard to finance and calking—The launching of the Spray. CHAPTER II Failure as a fisherman—A voyage around the world projected—From Boston to Gloucester—Fitting out for the ocean voyage—Half of a dory for a ship's boat—The run from Gloucester to Nova Scotia—A shaking up in home waters—Among old friends. -

THE ARCHAEOLOGY of ACHAEMENID RULE in EGYPT by Henry Preater Colburn a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requ

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF ACHAEMENID RULE IN EGYPT by Henry Preater Colburn A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Art and Archaeology) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Margaret C. Root, Chair Associate Professor Elspeth R. M. Dusinberre, University of Colorado Professor Sharon C. Herbert Associate Professor Ian S. Moyer Professor Janet E. Richards Professor Terry G. Wilfong © Henry Preater Colburn All rights reserved 2014 For my family: Allison and Dick, Sam and Gabe, and Abbie ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was written under the auspices of the University of Michigan’s Interdepartmental Program in Classical Art and Archaeology (IPCAA), my academic home for the past seven years. I could not imagine writing it in any other intellectual setting. I am especially grateful to the members of my dissertation committee for their guidance, assistance, and enthusiasm throughout my graduate career. Since I first came to Michigan Margaret Root has been my mentor, advocate, and friend. Without her I could not have written this dissertation, or indeed anything worth reading. Beth Dusinberre, another friend and mentor, believed in my potential as a scholar well before any such belief was warranted. I am grateful to her for her unwavering support and advice. Ian Moyer put his broad historical and theoretical knowledge at my disposal, and he has helped me to understand the real potential of my work. Terry Wilfong answered innumerable questions about Egyptian religion and language, always with genuine interest and good humor. Janet Richards introduced me to Egyptian archaeology, both its study and its practice, and provided me with important opportunities for firsthand experience in Egypt. -

12 Must-See Hidden Gems in Cairo

12 MUST-SEE HIDDEN GEMS IN CAIRO V A N I L L A P A P E R S . N E T For many visitors, sightseeing in Cairo is a rushed affair. There's too much to see, and a typical tour will usually push tourists through the major iconic sites without getting much into the spirit of the city or its modern-day life. Independent travellers, on the other hand, can often get stuck in tourist traps because there's just not enough info online about Cairo beyond the major tourist attractions. But there's more to the city than the pyramids and the old souq. You should visit those sites, of course, but if you want a better-rounded image of the city then make some time for these gems off the beaten tourist path. This is the Cairo of small museums, quirky bookshops, scenic parks and hip galleries that you won't find on a typical itinerary. It's the Cairo I've discovered in more than six years of living here as an expat, and in my years of working as a travel editor at a major magazine. I hope you'll enjoy these bars, concert venues and hidden mansions as much as I've come to love them. V A N I L L A P A P E R S . N E T 1.Darb 1718 See modern Egyptian art & rooftop concerts 263J+7P This is a modern art and culture center where you can catch exhibits of innovative and up- and- coming Egyptian artists in the heart of Old Cairo. -

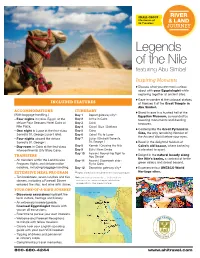

Legends of the Nile Featuring Abu Simbel

SMALL GROUP RIVER Ma xi mum of 28 Travele rs & LAND JO URNEY Legends of the Nile featuring Abu Simbel Inspiring Moments >Discuss what you are most curious about with your Egyptologist while exploring together at ancient sites. >Gaze in wonder at the colossal statues INCLUDED FEATURES of Ramses II at the Great Temple in Abu Simbel. ACCOMMODATIONS ITINERARY > A Stand in awe in a hushed hall of the (With baggage handling.) Day 1 Depart gateway city Egyptian Museum, surrounded by – Four nights in Cairo, Egypt, at the Day 2 Arrive in Cairo towering monuments and dazzling deluxe Four Seasons Hotel Cairo at Day 3 Cairo treasures. Nile Plaza. Day 4 Cairo | Giza | Sakkara >Contemplate the Great Pyramid in – One night in Luxor at the first-class Day 5 Cairo Giza, the only remaining Wonder of Sonesta St. George Luxor Hotel. Day 6 Cairo | Fly to Luxor the Ancient World before your eyes. – Four nights aboard the deluxe Day 7 Luxor | Embark Sonesta Sonesta St. George I. St. George I >Revel in the delightful hubbub of – Day room in Cairo at the first-class Day 8 Karnak | Cruising the Nile Cairo’s old bazaar, where bartering Intercontinental City Stars Cairo. Day 9 Edfu | Kom Ombo is elevated to sport. Day 10 Aswan | Round-trip flight to >Delight in the natural beauty along TRANSFERS Abu Simbel the Nile’s banks, a contrast of fertile – All transfers within the Land/Cruise Day 11 Aswan | Disembark ship | Program: flights and deluxe motor Fly to Cairo green valleys and desert beyond. coaches, including baggage handling.